Cranial nerves

| Cranial nerves | |

|---|---|

|

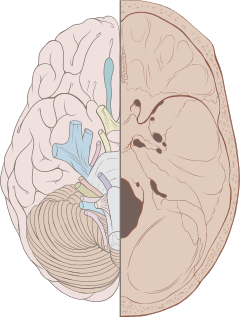

Left View of the human brain from below, showing origins of cranial nerves. Right Juxtaposed skull base with foramina in which many nerves exit the skull. | |

|

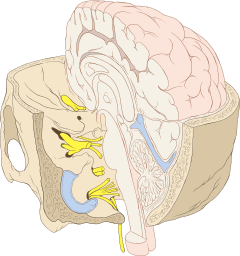

Cranial nerves as they pass through the skull base to the brain. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin |

nervus cranialis (pl: nervi craniales) |

| TA |

A14.2.01.001 A14.2.00.038 |

| FMA | 5865 |

| Cranial nerves |

|---|

|

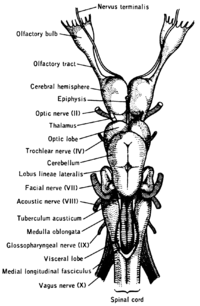

Cranial nerves are the nerves that emerge directly from the brain (including the brainstem), in contrast to spinal nerves (which emerge from segments of the spinal cord).[1] Cranial nerves relay information between the brain and parts of the body, primarily to and from regions of the head and neck.[2]

Spinal nerves emerge sequentially from the spinal cord with the spinal nerve closest to the head (C1) emerging in the space above the first cervical vertebra. The cranial nerves, however, emerge from the central nervous system above this level.[3] Each cranial nerve is paired and is present on both sides. Depending on definition in humans there are twelve or thirteen cranial nerves pairs, which are assigned Roman numerals I–XII, sometimes also including cranial nerve zero. The numbering of the cranial nerves is based on the order in which they emerge from the brain, front to back (brainstem).[1]

The terminal nerves, olfactory nerves (I) and optic nerves (II) emerge from the cerebrum or forebrain, and the remaining ten pairs arise from the brainstem, which is the lower part of the brain.[1]

The cranial nerves are considered components of the peripheral nervous system (PNS),[1] although on a structural level the olfactory, optic and terminal nerves are more accurately considered part of the central nervous system (CNS).[4]

Anatomy

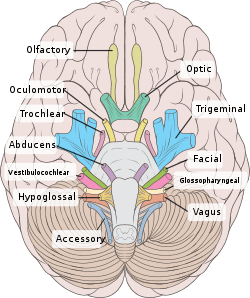

Most typically, humans are considered to have twelve pairs of cranial nerves (I–XII). They are: the olfactory nerve (I), the optic nerve (II), oculomotor nerve (III), trochlear nerve (IV), trigeminal nerve (V), abducens nerve (VI), facial nerve (VII), vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII), glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), vagus nerve (X), accessory nerve (XI), and hypoglossal nerve (XII). (There may be a thirteenth cranial nerve, the terminal nerve (nerve O or N), which is very small and may or may not be functional in humans[1][3])

Terminology

Cranial nerves are generally named according to their structure or function. For example, the olfactory nerve (I) supplies smell, and the facial nerve (VII) supplies motor innervation to the face. Because Latin was the lingua franca (common language) of the study of Anatomy when the nerves were first documented, recorded, and discussed, many nerves maintain Latin or Greek names, including the trochlear nerve (IV), named according to its structure, as it supplies a muscle that attaches to a pulley (Greek: trochlea). The trigeminal nerve (V) is named in accordance with its three components (Latin: tri-geminus meaning triplets),[5] and the vagus nerve (X) is named for its wandering course (Latin: vagus).[6]

Cranial nerves are numbered based on their rostral-caudal (front-back) position,[1] when viewing the brain. If the brain is carefully removed from the skull the nerves are typically visible in their numeric order.[7]

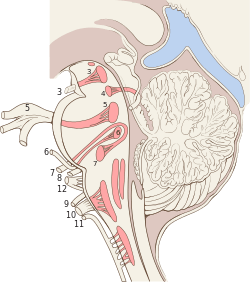

Cranial nerves have paths within and outside of the skull. The paths within the skull are called "intracranial" and the paths outside the skull are called "extracranial". There are many holes in the skull called "foramina" by which the nerves can exit the skull. All cranial nerves are paired, which means that they occur on both the right and left sides of the body. The muscle, skin, or additional function supplied by a nerve on the same side of the body as the side it originates from, is referred to an ipsilateral function. If the function is on the opposite side to the origin of the nerve, this is known as a contralateral function.[8]

Intracranial course

Nuclei

The cell bodies of many of the neurons of most of the cranial nerves are contained in one or more nuclei in the brainstem. These nuclei are important relative to cranial nerve dysfunction because damage to these nuclei such as from a stroke or trauma can mimic damage to one or more branches of a cranial nerve. In terms of specific cranial nerve nuclei, the midbrain of the brainstem has the nuclei of the oculomotor nerve (III) and trochlear nerve (IV); the pons has the nuclei of the trigeminal nerve (V), abducens nerve (VI), facial nerve (VII) and vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII); and the medulla has the nuclei of the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), vagus nerve (X), accessory nerve (XI) and hypoglossal nerve (XII). The fibers of these cranial nerves exit the brainstem from these nuclei.[1]

Ganglia

Some of the cranial nerves have sensory or parasympathetic ganglia (collections of cell bodies) of neurons, which are located outside of the brain (but can be inside or outside of the skull).[1]

The sensory ganglia are directly correspondent to dorsal root ganglia of spinal nerves and are known as cranial sensory ganglia.[7] Sensory ganglia exist for nerves with sensory function: V, VII, VIII, IX, X.[3] There are also parasympathetic ganglia, which are part of the autonomic nervous system for cranial nerves III, VII, IX and X.

- The trigeminal ganglia of the trigeminal nerve (V) occupies a space in the dura mater called Trigeminal cave. This ganglion contains the cell bodies of the sensory fibers of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve.

- The geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve (VII) is found just after the nerve enters the facial canal; it contains the cell bodies of the sensory fibers of the facial nerve.

- Superior and inferior ganglia of the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), are located just after the nerve passes through the jugular foramen and contain the cell bodies of the sensory fibers of this nerve.

- inferior ganglion of vagus nerve (nodose ganglion) is located below the jugular foramen and contains the cell bodies of the sensory fibers of the vagus nerve (X).

Exiting the skull and extracranial course

| Location | Nerve |

|---|---|

| cribriform plate | Olfactory nerve (I) |

| optic foramen | Optic nerve (II) |

| superior orbital fissure | Oculomotor (III) Trochlear (IV) Abducens (VI) Trigeminal V1 (ophthalmic) |

| Foramen rotundum | Trigeminal V2 (maxillary) |

| Foramen ovale | Trigeminal V3 (mandibular) |

| internal auditory canal | Facial (VII) Vestibulocochlear (VIII) |

| jugular foramen | Glossopharyngeal (IX) Vagus (X) Accessory (XI) |

| hypoglossal canal | Hypoglossal (XII) |

After emerging from the brain, the cranial nerves travel within the skull, and some must leave this bony compartment in order to reach their destinations. Often the nerves pass through holes in the skull, called foramina, as they travel to their destinations. Other nerves pass through bony canals, longer pathways enclosed by bone. These foramina and canals may contain more than one cranial nerve, and may also contain blood vessels.[9]

- The olfactory nerve (I), actually composed of many small separate nerve fibers, passes through perforations in the cribiform plate part of the ethmoid bone. These fibers terminate in the upper part of the nasal cavity and function to convey impulses containing information about odors to the brain.

- The optic nerve (II) passes through the optic foramen in the sphenoid bone as it travels to the eye. It conveys visual information to the brain.

- The oculomotor nerve (III), trochlear nerve (IV), abducens nerve (VI) and the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (V1) travel through the cavernous sinus into the superior orbital fissure, passing out of the skull into the orbit. These nerves control the small muscles that move the eye and also provide sensory innervation to the eye and orbit.

- The maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (V2) passes through foramen rotundum in the sphenoid bone to supply the skin of the middle of the face.

- The mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (V3) passes through foramen ovale of the sphenoid bone to supply the lower face with sensory innervation. This nerve also sends branches to almost all of the muscles that control chewing.

- The facial nerve (VII) and vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII) both enter the internal auditory canal in the temporal bone. The facial nerve then reaches the side of the face by using the stylomastoid foramen, also in the temporal bone. Its fibers then spread out to reach and control all of the muscles of facial expression. The vestibulocochlear nerve reaches the organs that control balance and hearing in the temporal bone, and therefore does not reach the external surface of the skull.

- The glossopharyngeal (IX), vagus (X) and accessory nerve (XI) all leave the skull via the jugular foramen to enter the neck. The glossopharyngeal nerve provides innervation to the upper throat and the back of the tongue, the vagus provides innervation to the muscles in the voicebox, and continues downward to supply parasympathetic innervation to the chest and abdomen. The accessory nerve controls two muscles in the neck and shoulder.

- The hypoglossal nerve (XII) exits the skull using the hypoglossal canal in the occipital bone and reaches the tongue to control almost all of the muscles involved in movements of this organ.[1]

Function

The cranial nerves provide motor and sensory innervation mainly to the structures within the head and neck. The sensory innervation includes both "general" sensation such as temperature and touch, and "special" innervation such as taste, vision, smell, balance and hearing[1][10]

The vagus nerve (X) provides sensory and autonomic (parasympatheic) motor innervation to structures in the neck and also to most of the organs in the chest and abdomen.[1][3]

Smell (I)

The olfactory nerve (I) conveys the sense of smell.

Damage to the olfactory nerve (I) can cause an inability to smell (anosmia), a distortion in the sense of smell (parosmia), or a distortion or lack of taste. If there is suspicion of a change in the sense of smell, each nostril is tested with substances of known odors such as coffee or soap. Intensely smelling substances, for example ammonia, may lead to the activation of pain receptors (nociceptors) of the trigeminal nerve that are located in the nasal cavity and this can confound olfactory testing.[1][11]

Vision (II)

The optic nerve (II) transmits visual information.[3][10]

Damage to the optic nerve (II) affects specific aspects of vision that depend on the location of the lesion. A person may not be able to see objects on their left or right sides (homonymous hemianopsia), or may have difficulty seeing objects on their outer visual fields (bitemporal hemianopsia) if the optic chiasm is involved.[12] Vision may be tested by examining the visual field, or by examining the retina with an ophthalmoscope, using a process known as funduscopy. Visual field testing may be used to pin-point structural lesions in the optic nerve, or further along the visual pathways.[11]

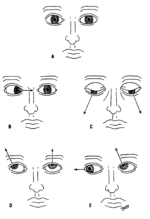

Eye movement (III, IV, VI)

The oculomotor nerve (III), trochlear nerve (IV) and abducens nerve (VI) coordinate eye movement.

Damage to nerves III, IV, or VI may affect the movement of the eyeball (globe). Both or one eye may be affected; in either case double vision (diplopia) will likely occur because the movements of the eyes are no longer synchronized. Nerves III, IV and VI are tested by observing how the eye follows an object in different directions. This object may be a finger or a pin, and may be moved at different directions to test for pursuit velocity.[11] If the eyes do not work together, the most likely cause is damage to a specific cranial nerve or its nuclei.[11]

Damage to the oculomotor nerve (III) can cause double vision (diplopia) and inability to coordinate the movements of both eyes (strabismus), also eyelid drooping (ptosis) and pupil dilation (mydriasis).[12][12] Lesions may also lead to inability to open the eye due to paralysis of the levator palpebrae muscle. Individuals suffering from a lesion to the oculomotor nerve may compensate by tilting their heads to alleviate symptoms due to paralysis of one or more of the eye muscles it controls.[11]

Damage to the trochlear nerve (IV) can also cause diplopia with the eye adducted and elevated.[12] The result will be an eye which can not move downwards properly (especially downwards when in an inward position). This is due to impairment in the superior oblique muscle, which is innervated by the trochlear nerve.[11]

Damage to the abducens nerve (VI) can also result in diplopia.[12] This is due to impairment in the lateral rectus muscle, which is innervated by the abducens nerve.[11]

Trigeminal nerve (V)

The trigeminal nerve (V) is composed of three distinct parts: The Ophthalmic (V1), the Maxillary (V2), and the Mandibular (V3) nerves. Combined, these nerves provide sensation to the skin of the face and also controls the muscles of mastication (chewing).[1] Conditions affecting the trigeminal nerve (V) include trigeminal neuralgia,[1] cluster headache,[13] and trigeminal zoster.[1] Trigeminal neuralgia occurs later in life, from middle age onwards, most often after age 60, and is a condition typically associated with very strong pain distributed over the area innervated by the maxillary or mandibular nerve divisions of the trigeminal nerve (V2 and V3).[14]

Facial expression (VII)

Lesions of the facial nerve (VII) may manifest as facial palsy. This is where a person is unable to move the muscles on one or both sides of their face. A very common and generally temporarly facial palsy is known as Bell's palsy. Bell's Palsy is the result of an idiopathic (unknown), unilateral lower motor neuron lesion of the facial nerve and is characterized by an inability to move the ipsilateral muscles of facial expression, including elevation of the eyebrow and furrowing of the forehead. Patients with Bell's palsy often have a drooping mouth on the affected side and often have trouble chewing because the buccinator muscle is affected.[1]

Hearing and balance (VIII)

The vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII) splits into the vestibular and cochlear nerve. The vestibular part is responsible for innervating the vestibules and semicircular canal of the inner ear; this structure transmits information about balance, and is an important component of the vestibuloocular reflex, which keeps the head stable and allows the eyes to track moving objects. The cochlear nerve transmits information from the cochlea, allowing sound to be heard.[3]

When damaged, the vestibular nerve may give rise to the sensation of spinning and dizziness. Function of the vestibular nerve may be tested by putting cold and warm water in the ears and watching eye movements caloric stimulation.[1][11] Damage to the vestibulocochlear nerve can also present as repetitive and involuntary eye movements (nystagmus), particularly when looking in a horizontal plane.[11] Damage to the cochlear nerve will cause partial or complete deafness in the affected ear.[11]

Oral sensation, taste, and salivation (IX)

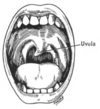

The glossopharyngeal nerve (IX) innervates the stylopharyngeus muscle and provides sensory innervation to the oropharynx and back of the tongue.[1][15] The glossopharyngeal nerve also provides parasympathetic innervation to the parotid gland.[1] Unilateral absence of a gag reflex suggests a lesion of the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), and perhaps the vagus nerve (X).[16]

Vagus nerve (X)

Loss of function of the vagus nerve (X) will lead to a loss of parasympathetic innervation to a very large number of structures. Major effects of damage to the vagus nerve may include a rise in blood pressure and heart rate. Isolated dysfunction of only the vagus nerve is rare, but can be diagnosed by a hoarse voice, due to dysfunction of one of its branches, the recurrent laryngeal nerve.[1]

Damage to this nerve may result in difficulties swallowing.[11]

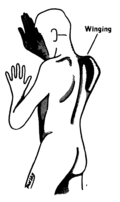

Shoulder elevation and head-turning (XI)

Damage to the accessory nerve (XI) will lead to ipsilateral weakness in the trapezius muscle. This can be tested by asking the subject to raise their shoulders or shrug, upon which the shoulder blade ( scapula) will protrude into a winged position.[1] Additionally, if the nerve is damaged, weakness or an inability to elevate the scapula may be present because the levator scapulae muscle is now solely able to provide this function.[14] Depending on the location of the lesion there may also be weakness present in the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which acts to turn the head so that the face points to the opposite side.[1]

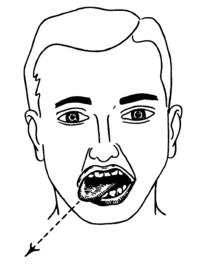

Tongue movement (XII)

The hypoglossal nerve (XII) is unique in that it is innervated from both the motor cortex of both hemispheres of the brain. Damage to the nerve at lower motor neuron level may lead to fasciculations or atrophy of the muscles of the tongue. The fasciculations of the tongue are sometimes said to look like a "bag of worms". Upper motor neuron damage will not lead to atrophy or fasciculations, but only weakness of the innervated muscles.[11]

When the nerve is damaged, it will lead to weakness of tongue movement on one side. When damaged and extended, the tongue will move towards the weaker or damaged side, as shown in the image.[11]

Clinical significance

Examination

Physicians, neurologists, and other medical professionals may conduct a cranial nerve examination as part of a neurological examination to examine the functionality of the cranial nerves. This is a highly formalized series of tests that assess the status of each nerve.[18] A cranial nerve exam begins with observation of the patient because some cranial nerve lesions may affect the symmetry of the eyes or face. The visual fields are tested for nerve lesions or nystagmus via an analysis of specific eye movements. The sensation of the face is tested, and patients are asked to perform different facial movements, such as puffing out of the cheeks. Hearing is checked by voice and tuning forks. The position of the patient's uvula is examined because asymmetry in the position could indicate a lesion of the glossopharyngeal nerve. After the ability of the patient to use their shoulder to assess the accessory nerve (XI), and the patient's tongue function is assessed by observing various tongue movements.[1][18]

Damage

Compression

Nerves may be compressed because of increased intercranial pressure, a mass effect of an intracerebral haemorrhage, or tumour that presses against the nerves and interferes with the transmission of impulses along the nerve.[19] A loss of functionality of a single cranial nerve may sometimes be the first symptom of an intracranial or skull base cancer.[20]

An increase in intracranial pressure may lead to impairment of the optic nerves (II) due to compression of the surrounding veins and capillaries, causing swelling of the eyeball (papilloedema).[21] A cancer, such as an optic glioma, may also impact the optic nerve (II). A pituitary tumour may compress the optic tracts or the optic chiasm of the optic nerve (II), leading to visual field loss. A pituitary tumour may also extend into the cavernous sinus, compressing the oculuomotor nerve (III), trochlear nerve (IV) and abducens nerve (VI), leading to double-vision and strabismus. These nerves may also be affected by herniation of the temporal lobes of the brain through the falx cerebri.[19]

The cause of trigeminal neuralgia, in which one side of the face is exquisitely painful, is thought to be compression of the nerve by an artery as the nerve emerges from the brain stem.[19] An acoustic neuroma, particularly at the junction between the pons and medulla, may compress the facial nerve (VII) and vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII), leading to hearing and sensory loss on the affected side.[19][22]

Stroke

Occlusion of blood vessels that supply the nerves or their nuclei, an ischemic stroke, may cause specific signs and symptoms that can localise where the occlusion occurred. A clot in a blood vessel draining the cavernous sinus (cavernous sinus thrombosis) affects the oculomotor (III), trochlear (IV), opthalamic branch of the trigeminal nerve (V1) and the abducens nerve (VI).[22]

Inflammation

Inflammation resulting from infection may impair the function of any of the cranial nerves. Inflammation of the facial nerve (VII) may result in Bell's palsy.[23]

Multiple sclerosis, an inflammatory process that may produce a loss of the myelin sheathes which surround the cranial nerves, may cause a variety of shifting symptoms affecting multiple cranial nerves.[23]

Other

Trauma to the skull, disease of bone such as Paget's disease, and injury to nerves during neurosurgery (such as tumor removal) are other possible causes of cranial nerve damage.[22]

History

Galen (AD 129–210) named seven pairs of cranial nerves. Much later, in 1664, Sir Thomas Willis suggested that there were actually 10 pairs of nerves. Finally, in 1778, Soemmering described the 12 pairs of nerves that are generally accepted today. However, because many of the nerves emerge from the brain stem as rootlets, there is continual debate as to how many nerves there actually are, and how they should be grouped. There is reason to consider both the olfactory (I) and Optic (II) nerves to be brain tracts, rather than cranial nerves. Further, the very small terminal nerve (nerve N or O) exists in humans but may not be functional. In other animals, it appears to be important to sexual receptivity based on perceptions of phermones[1][24]

Other animals

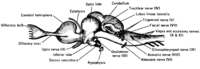

top; ventral bottom; lateral

The accessory nerve (XI) and hypoglossal nerve (XII) cannot be seen, as they are not always present in all vertebrates.

Cranial nerves are also present in other vertebrates. Other amniotes (non-amphibian tetrapods) have cranial nerves similar to those of humans. In anamniotes (fishes and amphibians), the accessory nerve (XI) and hypoglossal nerve (XII) do not exist, with the accessory nerve (XI) being an integral part of the vagus nerve (X); the hypoglossal nerve (XII) is represented by a variable number of spinal nerves emerging from vertebral segments fused into the occiput. These two nerves only became discrete nerves in the ancestors of amniotes (non-amphibian tetrapods).[25]

Diagrammatic view of the cranial nerves of the horse.

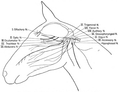

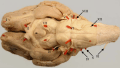

Diagrammatic view of the cranial nerves of the horse. Ventral view of the sheep's brain. The exits of the various cranial nerves are marked with red.

Ventral view of the sheep's brain. The exits of the various cranial nerves are marked with red.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Vilensky, Joel; Robertson, Wendy; Suarez-Quian, Carlos (2015). The Clinical Anatomy of the Cranial Nerves: The Nerves of "On Olympus Towering Top". Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-49201-7.

- ↑ Standring, Susan; Borley, Neil R. (2008). "Overview of cranial nerves and cranial nerve nuclei". Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). [Edinburgh]: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06684-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kandel, Eric R. (2013). Principles of neural science (5 ed.). Appleton and Lange: McGraw Hill. pp. 1019–1036. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ↑ Board Review Series – Neuroanatomy, Fourth Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Maryland 2008, p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7817-7245-7.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Trigeminal Nerve". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ Davis, Matthew C.; Griessenauer, Christoph J.; Bosmia, Anand N.; Tubbs, R. Shane; Shoja, Mohammadali M. "The naming of the cranial nerves: A historical review". Clinical Anatomy. 27 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1002/ca.22345.

- 1 2 Mallatt, Elaine N. Marieb, Patricia Brady Wilhelm, Jon (2012). Human anatomy (6th ed. media update. ed.). Boston: Benjamin Cummings. pp. 431–432. ISBN 978-0-321-75327-4.

- ↑ Albert, Daniel (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- 1 2 Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 800–807. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- 1 2 Mtui, M.J. Turlough FitzGerald, Gregory Gruener, Estomih (2012). Clinical neuroanatomy and neuroscience (6th ed.). [Edinburgh?]: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7020-3738-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Kandel, Eric R. (2013). Principles of neural science (5. ed.). Appleton and Lange: McGraw Hill. pp. 1533–1549. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Norton, Neil (2007). Netter's head and neck anatomy for dentistry. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-929007-88-2.:78

- ↑ Nesbitt AD, Goadsby PJ (Apr 11, 2012). "Cluster headache". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) (Review). 344: e2407. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2407. PMID 22496300.

- 1 2 Fitzgerald, M.J. Turlough FitzGerald, Gregory Gruener, Estomih Mtui (2012). Clinical neuroanatomy and neuroscience (6th ed.). [Edinburgh?]: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-7020-3738-2.

- ↑ Mtui, M.J. Turlough FitzGerald, Gregory Gruener, Estomih (2012). Clinical neuroanatomy and neuroscience (6th ed.). [Edinburgh?]: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 220–222. ISBN 978-0-7020-3738-2.

- ↑ Bickley, Lynn S., Peter G. Szilagyi, and Barbara Bates. Bates' Guide to Physical Examination and History-taking. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013. Print.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Sudipta; Gowshami, Chandra; Salam, Abdus; Kuddus, Ruhul; Farazi, Mohshin; Baksh, Jahid (2014-01-01). "A case with unilateral hypoglossal nerve injury in branchial cyst surgery". Journal of Brachial Plexus and Peripheral Nerve Injury. 07 (01). doi:10.1186/1749-7221-7-2. PMC 3395866

. PMID 22296879.

. PMID 22296879. - 1 2 O'Connor, Nicholas J. Talley, Simon (2009). Clinical examination : a systematic guide to physical diagnosis (6th ed.). Chatswood, N.S.W.: Elsevier Australia. pp. 330–352. ISBN 978-0-7295-3905-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Britton, the editors Nicki R. Colledge, Brian R. Walker, Stuart H. Ralston ; illustrated by Robert (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 787, 1215–1217. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ↑ Kumar (), Vinay; et al. (2010). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 1266. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5.

- ↑ Britton, the editors Nicki R. Colledge, Brian R. Walker, Stuart H. Ralston ; illustrated by Robert (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 1166. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- 1 2 3 Fauci, Anthony S.; Harrison, T. R., eds. (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 2583–2587. ISBN 978-0-07-147693-5.

- 1 2 Britton, the editors Nicki R. Colledge, Brian R. Walker, Stuart H. Ralston ; illustated by Robert (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 1164–1170, 1192–1193. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ↑ Vilensky JA, The neglected cranial nerve: nerves terminus (Cranial nerve N). Clin Anat. 2014 Jan;27(1) PMID 22836597

- ↑ Quiring, Daniel Paul (1950). Functional anatomy of the vertebrates. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 249.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cranial nerves. |

- Cranial nerve video (Brainfacts.org)

- 3,7 3,7 Ocular motor system & control (Neuroscience online textbook)

- Yale Cranial nerve review (Yale Center for Advanced Instructional Media)

- Cranial nerve animations (University of Liverpool Veterinary School).

- Cranial nerve quiz (unires.info).