Reptiles in culture

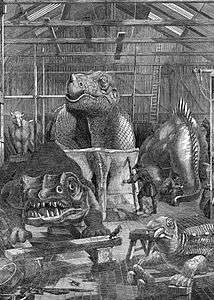

Reptiles have featured in culture for centuries, from scaled and winged mythical dragons, versions of real reptiles such as deceptive snakes and dangerous crocodiles, to dinosaurs, discovered in the nineteenth century and by 1854 represented to the public as the large-scale sculptures of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. Practical uses of reptiles include the manufacture of snake antivenom, and the farming of crocodiles, principally for leather but also for meat.

Mythical reptiles

Dragon

A dragon is a legendary creature, typically with snake-like or reptilian traits, in the myths of both European and Chinese cultures, with counterparts in Japan, Korea and other East Asian countries.[1]

Dinosaurs

Dinosaurs have been widely depicted in culture since the English palaeontologist Richard Owen coined the name dinosaur in 1842. As soon as 1854, the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs were on display to the public in south London.[2][3] One dinosaur appeared in literature even earlier, as Charles Dickens placed a Megalosaurus in the first chapter of his novel Bleak House in 1852.[4]

The dinosaurs featured in books, films, television programs, artwork, and other media have been used for both education and entertainment. The depictions range from the realistic, as in the television documentaries of the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, or the fantastic, as in the monster movies of the 1950s and 1960s.[3][5][6]

The growth in interest in dinosaurs since the Dinosaur Renaissance has been accompanied by depictions made by artists working with ideas at the leading edge of dinosaur science, presenting lively dinosaurs and feathered dinosaurs as these concepts were first being considered. Cultural depictions of dinosaurs have been an important means of translating scientific discoveries to the public.[5]

Cultural depictions have also created or reinforced misconceptions about dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals, such as inaccurately and anachronistically portraying a sort of "prehistoric world" where many kinds of extinct animals (from the Permian animal Dimetrodon to mammoths and cavemen) lived together, and dinosaurs living lives of constant combat.[3][7]

Other misconceptions reinforced by cultural depictions came from a scientific consensus that has now been overturned, such as the alternate usage of dinosaur to describe something that is maladapted or obsolete, or dinosaurs as slow and unintelligent.[3][8]

Living reptiles

Crocodile

Large crocodiles, especially the saltwater crocodile and Nile crocodile, attack and kill hundreds of people each year in Southeast Asia and Africa.[9]

Crocodiles are protected in many parts of the world, and are farmed commercially. Their hides are tanned and used to make leather goods such as shoes and handbags; crocodile meat is also considered a delicacy.[10] The most commonly farmed species are the saltwater and Nile crocodiles. Farming has resulted in an increase in the saltwater crocodile population in Australia, as eggs are usually harvested from the wild, so landowners have an incentive to conserve their habitat. Crocodile leather is made into wallets, briefcases, purses, handbags, belts, hats, and shoes. Crocodile oil has been used for various purposes.[11] Crocodile meat is occasionally eaten as an "exotic" delicacy in the western world.[12]

Crocodiles have appeared in religions across the world. Ancient Egypt had Sobek, the crocodile-headed god, with his cult-city Crocodilopolis, as well as Taweret, the goddess of childbirth and fertility, with the back and tail of a crocodile.[13] In Hinduism, Varuna, a Vedic and Hindu god, rides a part-crocodile makara; his consort Varuni rides a crocodile.[14] Similarly the goddess personifications of the Ganga and Yamuna rivers are often depicted as riding crocodiles.[15][16][17] In Goa, crocodile worship is practised, as at the annual Mannge Thapnee ceremony.[18] In Latin America, Cipactli was the giant earth crocodile of the Aztec and other Nahua peoples.[19]

The supposed weeping of insincere crocodile tears is derived from an ancient anecdote that crocodiles weep to lure their prey, or that they cry for the victims they are eating, first told in the Bibliotheca by Photios.[20] The story is repeated in bestiaries such as De bestiis et aliis rebus. This tale was first spread widely in English in the stories of the travels of Sir John Mandeville in the 14th century, and appears in several of Shakespeare's plays.[21] In fact, crocodiles can generate tears, but they do not cry.[22]

Snake

Deaths from snakebites are uncommon in many parts of the world, but are still counted in tens of thousands per year in India.[23] Snakebite can be treated with antivenom made from the venom of the snake. To produce antivenom, a mixture of the venoms of different species of snake is injected into the body of a horse in ever-increasing dosages until the horse is immunized. Blood is then extracted; the serum is separated, purified and freeze-dried.[24]

In India, snake charming is a traditional roadside show. The snake charmer carries a basket that contains a snake to which he plays tunes from his flute, to which the snake appears to dance.[25] Snakes respond to the movement of the flute, not the actual noise.[25][26]

Snake soup is made in Cantonese cuisine.[27] In China, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam and Cambodia, drinking the blood of the cobra is believed to increase sexual virility.[28] Snake wine (蛇酒) is an alcoholic beverage produced by infusing whole snakes in rice wine or grain alcohol. The drink was first recorded to have been consumed in China during the Western Zhou dynasty and considered an important curative and believed to reinvigorate a person according to Traditional Chinese medicine.[29]

In the Western world, some snakes (especially docile species such as the ball python and corn snake) are kept as pets.[30]

The snake or serpent has played a powerful symbolic role in different cultures. In Egyptian history, the Nile cobra adorned the crown of the pharaoh. It was worshipped as one of the gods and was also used for sinister purposes: murder of an adversary and ritual suicide (Cleopatra). In Greek mythology snakes are associated with deadly antagonists, as a chthonic symbol, roughly translated as 'earthbound'. The nine-headed Lernaean Hydra that Hercules defeated and the three Gorgon sisters are children of Gaia, the earth. Medusa was one of the three Gorgon sisters who Perseus defeated. Medusa is described as a hideous mortal, with snakes instead of hair and the power to turn men to stone with her gaze. After killing her, Perseus gave her head to Athena who fixed it to her shield called the Aegis. The Titans are also depicted in art with snakes instead of legs and feet for the same reason—they are children of Gaia and Uranus, so they are bound to the earth.[31]

Three medical symbols involving snakes, still used today, are the Bowl of Hygieia symbolizing pharmacy, and the Caduceus and Rod of Asclepius, symbols of medicine.[32]

In India, snakes are worshipped as gods, with many women pouring milk on snake pits. The cobra is seen on the neck of Shiva, while Vishnu is depicted often as sleeping on a seven-headed snake or within the coils of a serpent. There are temples in India solely for cobras sometimes called Nagraj (King of Snakes), and it is believed that snakes are symbols of fertility. In the annual Hindu festival of Nag Panchami, snakes are venerated and prayed to.[33]

The ouroboros is a widely used symbol, claimed to be related to alchemy. It is depicted as a coiled snake eating its own tail, representing the cycle of life, death and rebirth. The snake is one of the 12 celestial animals of the Chinese Zodiac. Ancient Peruvian cultures often depicted snakes.[34][35]

In religious terms, the snake and jaguar are arguably the most important animals in ancient Mesoamerica. "In states of ecstasy, lords dance a serpent dance; great descending snakes adorn and support buildings from Chichen Itza to Tenochtitlan, and the Nahuatl word coatl meaning serpent or twin, forms part of primary deities such as Mixcoatl, Quetzalcoatl, and Coatlicue."[36]

In Christianity and Judaism, a serpent appears in Genesis 3:1 to tempt Adam and Eve with the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge. In Neo-Paganism and Wicca, the snake is seen as a symbol of wisdom and knowledge.

The cytotoxic effect of snake venom is being researched as a potential treatment for cancers.[37]

Turtle

The tortoise is a symbol of wisdom and knowledge, and is able to defend itself on its own. It personifies water, the moon, the Earth, time, immortality, and fertility. Creation is associated with the tortoise and it is also believed that the tortoise bears the burden of the whole world.[38] The turtle has a prominent position as a symbol of steadfastness and tranquility in religion, mythology, and folklore from around the world.[39] A tortoise's longevity is suggested by its long lifespan and its shell, which was thought to protect it from any foe.[40] In the cosmological myths of several cultures a World Turtle carries the world upon its back or supports the heavens.[41]

References

- ↑ Ingersoll, Ernest et al., (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Cognoscenti Books

- ↑ Torrens, Hugh. "Politics and Paleontology". The Complete Dinosaur, 175–190.

- 1 2 3 4 Glut, Donald F.; Brett-Surman, Michael K. (1997). "Dinosaurs and the media". The Complete Dinosaur. Indiana University Press. pp. 675–706. ISBN 0-253-33349-0.

- ↑ "London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln's Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborne Hill." From page 1 of Dickens, Charles J.H. (1852). Bleak House, Chapter I: In Chancery. London: Bradbury & Evans.

- 1 2 Paul, Gregory S. (2000). "The Art of Charles R. Knight". In Paul, Gregory S. The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. St. Martin's Press. pp. 113–118. ISBN 0-312-26226-4.

- ↑ Searles, Baird (1988). "Dinosaurs and others". Films of Science Fiction and Fantasy. New York: AFI Press. pp. 104–116. ISBN 0-8109-0922-7.

- ↑ Lucas, Spencer G. (2000). "Dinosaurs in the public eye". Dinosaurs: The Textbook (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 247–260. ISBN 0-07-303642-0.

- ↑ "dinosaur". Dictionary.com. Lexico. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ "Crocodilian Attacks". IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ Lyman, Rick (30 November 1998). "Anahuac Journal; Alligator Farmer Feeds Demand for All the Parts". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ Country Folk Medicine: Tales of Skunk Oil, Sassafras Tea, and Other Old-time Remedies (2004) Elisabeth Janos. p. 56.

- ↑ Armstrong, Hilary (8 April 2009). "Best exotic restaurants in London". Evening Standard. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ Harris, Catherine C. "Egypt: The Crocodile God, Sobek". Tour Egypt.

- ↑ "The Crocodile Files". One World Magazine. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ "Holy Rivers, Lakes, and Oceans". Heart of Hinduism. ISKCON Educational Services. 2004.

Most rivers are considered female and are personified as goddesses. Ganga, who features in the Mahabharata, is usually shown riding on a crocodile (see right).

- ↑ Kumar, Nitin (August 2003). "Ganga The River Goddess - Tales in Art and Mythology".

- ↑ "Hindu gods and their holy mounts". Sri. Venkateswara Zoological Park.

The river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna, were appropriately mounted on a tortoise and a crocodile respectively.

- ↑ "The Crocodile is God in Goa" (PDF). Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter. 14 (1): 8. January–March 1995.

- ↑ Black, John. "Cipactli and Aztec Creation". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ Photius (1977). Bibliothèque. Tome VIII : Codices 257-280. (in French and Ancient Greek). R. Henry (trans.). Les Belles Lettres. p. 93. ISBN 978-2-251-32227-8.

- ↑ Ashton, John (2009). Curious creatures in zoology. ISBN 978-1-4092-3184-4.

- ↑ Britton, Adam (n.d.). Do crocodiles cry 'crocodile tears'? Crocodilian Biology Database. Retrieved March 13, 2006 from the Crocodile Specialist Group, Crocodile Species List, FAQ.

- ↑ Sinha, Kounteya (25 July 2006). "No more the land of snake charmers...". The Times of India.

- ↑ "Rattlesnake bite in a patient with horse allergy and von Willebrand's disease: case report" (PDF). Can Fam Physician. 42: 2207–11. 1996. PMC 2146932

. PMID 8939322.

. PMID 8939322. - 1 2 Bagla, Pallava (23 April 2002). "India's Snake Charmers Fade, Blaming Eco-Laws, TV". National Geographic News. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ "Snake charmer's bluff" International Wildlife Encyclopedia, 3rd edition, page 482

- ↑ Irvine, F. R. (1954). "Snakes as food for man". British Journal of Herpetology. 1 (10): 183–189.

- ↑ Flynn, Eugene (23 April 2002). "Flynn Of The Orient Meets The Cobra". Fabulous Travel. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ↑ "蛇酒的泡制与药用(The production and medicinal qualities of snake wine)". 9 April 2007.

- ↑ Ernest, Carl; George R. Zug; Molly Dwyer Griffin (1996). Snakes in Question: The Smithsonian Answer Book. Smithsonian Books. p. 203. ISBN 1-56098-648-4.

- ↑ Bullfinch, Thomas (2000). Bullfinch's Complete Mythology. London: Chancellor Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-7537-0381-5.

- ↑ Wilcox, Robert A.; Whitham, Emma M (15 April 2003). "The symbol of modern medicine: why one snake is more than two". Annals of Internal Medicine. 138 (8): 673–7. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00016. PMID 12693891. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ↑ Deane, John (1833). The Worship of the Serpent. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 61–64. ISBN 1-56459-898-5.

- ↑ Benson, Elizabeth (1972). The Mochica: A Culture of Peru. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-72001-0.

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine; Larco Museum (1997). The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01802-6.

- ↑ The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. Miller, Mary 1993 Thames & Hudson. London ISBN 978-0-500-27928-1

- ↑ Vivek Kumar Vyas, Keyur Brahmbahtt, Ustav Parmar; Brahmbhatt; Bhatt; Parmar (February 2012). "Theraputic potential of snake venom in cancer therapy: current perspective". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 3 (2): 156–162. doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60042-8. PMC 3627178

. PMID 23593597.

. PMID 23593597. - ↑ http://www.eedi.org.ua/eem/3-11eng.html

- ↑ Plotkin, Pamela, T., 2007, Biology and Conservation of Ridley Sea Turtles, Johns Hopkins University, ISBN 0-8018-8611-2.

- ↑ Ball, Catherine, 2004, Animal Motifs in Asian Art, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-43338-2.

- ↑ Stookey, Lorena Laura, 2004, Thematic Guide to World Mythology, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-31505-1.