Fish in culture

Fish play many roles in culture, from their economic importance in the fishing industry and fish farming, to recreational fishing, folklore, mythology, religion, art, literature, and film.

Economic uses

.jpg)

Throughout history, humans have utilized fish as a food source. Historically and today, most fish protein has come by means of catching wild fish. However, fish farming, which has been practiced since about 3,500 BC in China,[1] is becoming increasingly important in many nations. Overall, about one-sixth of the world's protein is estimated to be provided by fish.[2] Fisheries provide income for millions of people.[2][3]

In recreation

Fish have been recognized as a source of beauty for almost as long as used for food, appearing in cave art, being raised as ornamental fish in ponds, and displayed in aquariums in homes, offices, or public settings. Some smaller and more colourful species, and sometimes painted fish, serve as ornamental fish in ponds and aquariums, and as pets.[4]

Angling is fishing for pleasure or competition, with a rod, reel, line, hooks and bait. It has been practised for centuries, providing pleasure and employment.[5]

In science

Medaka and zebrafish are used as research models for studies in genetics and developmental biology. The zebrafish is the most commonly used laboratory vertebrate,[4] offering the advantages of similar genetics to mammals, small size, simple environmental needs, transparent larvae permitting non-invasive imaging, plentiful offspring, rapid growth, and the ability to absorb mutagens added to their water.[6]

In art

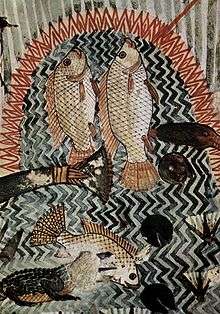

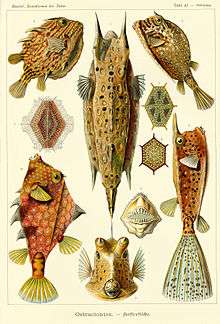

Fish have been frequent subjects in art, reflecting their economic importance, for at least 14,000 years. They were commonly worked into patterns in Ancient Egypt, acquiring mythological significance in Ancient Greece and Rome, and from there into Christianity as a religious symbol; artists in China and Japan similarly use fish images symbolically. Teleosts became common in Renaissance art, with still life paintings reaching a peak of popularity in the Netherlands in the 17th century. In the 20th century, different artists such as Klee, Magritte, Matisse and Picasso used representations of teleosts to express radically different themes, from attractive to violent.[7] The zoologist and artist Ernst Haeckel painted teleosts and other animals in his 1904 Kunstformen der Natur. Haeckel had become convinced by Goethe and Alexander von Humboldt that making accurate depictions of unfamiliar natural forms, such as from the deep oceans, he could not only discover "the laws of their origin and evolution but also to press into the secret parts of their beauty by sketching and painting".[8]

Wall painting of fishing, Tomb of Menna the scribe, Thebes, Ancient Egypt, c. 1422–1411 BC

Wall painting of fishing, Tomb of Menna the scribe, Thebes, Ancient Egypt, c. 1422–1411 BC- Italian Renaissance: Fish, Antonio Tanari, c. 1610–1630, in the Medici Villa, Poggio a Caiano

Mandarin Fish by Bian Shoumin, Qing Dynasty, 18th century

Mandarin Fish by Bian Shoumin, Qing Dynasty, 18th century Saito Oniwakamaru fights a giant carp at the Bishimon waterfall by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 19th century

Saito Oniwakamaru fights a giant carp at the Bishimon waterfall by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 19th century "Ostraciontes" by Ernst Haeckel, 1904. Ten fish with Lactoria cornuta in centre.

"Ostraciontes" by Ernst Haeckel, 1904. Ten fish with Lactoria cornuta in centre.- Fish Magic, Paul Klee, oil and watercolour varnished, 1925

In literature and film

Fish feature prominently in literature and film, as in books such as The Old Man and the Sea. Large fish, particularly sharks, have frequently been the subject of horror films and thrillers, most notably the novel Jaws, which spawned a series of films of the same name. Piranhas are shown in a similar light to sharks in films such as Piranha.[9] Legends of half-human, half-fish mermaids have featured in folklore, like the stories of Hans Christian Andersen.

In folklore, religion and mythology

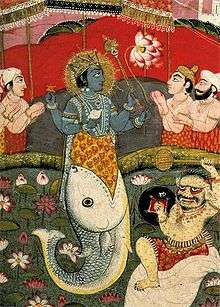

Fish themes have symbolic significance in many religions. The fish is a symbol of Jesus in Christians Christianity.[10] In the dhamma of Buddhism the fish symbolize happiness as they have complete freedom of movement in the water. Often drawn in the form of carp which are regarded in the Orient as sacred on account of their elegant beauty, size and life-span. Among the deities said to take the form of a fish are Ika-Roa of the Polynesians, Dagon of various ancient Semitic peoples, the shark-gods of Hawaiʻi and Matsya of the Hindus.

The astrological symbol Pisces is based on a constellation of the same name, but there is a second fish constellation in the night sky, Piscis Austrinus.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Spalding, Mark (July 11, 2013). "Sustainable Ancient Aquaculture". National Geographic. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- 1 2 Helfman, Gene S. (2007). Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources. Island Press. p. 11. ISBN 1597267600.

- ↑ "World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture" (PDF). fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- 1 2 Kisia, S. M. (2010). Vertebrates: Structures and Functions. CRC Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4398-4052-8.

- ↑ "New Economic Report Finds Commercial and Recreational Saltwater Fishing Generated More Than Two Million Jobs". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ "Five reasons why zebrafish make excellent research models". NC3RS. 10 April 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Moyle, Peter B.; Moyle, Marilyn A. (May 1991). "Introduction to fish imagery in art". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 31 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1007/bf00002153.

- ↑ Richards, Robert J. "The Tragic Sense of Ernst Haeckel: His Scientific and Artistic Struggles" (PDF). University of Chicago. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Zollinger, Sue Anne (3 July 2009). "Piranha–Ferocious Fighter or Scavenging Softie?". A Moment of Science. Indiana Public Media. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ↑ Coffman, Elesha (8 August 2008). "What is the origin of the Christian fish symbol?". Christianity Today. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "Piscis Austrinus". allthesky.com. The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations. Retrieved 1 November 2015.