Animal epithet

An animal epithet is a name used to label a person or group, by association with some perceived quality of an animal. Epithets may be formulated as similes, explicitly comparing people with the named animal, or as metaphors, directly naming people as animals. Animal epithets may be pejorative, readily giving offence, but they are also used in political campaigns. One English epithet, lamb, is always used positively.

Animal similes and metaphors have been used since classical times, for example by Homer and Virgil, to heighten effects in literature, and to sum up complex concepts concisely.

Surnames that name animals are found in different countries. They may be metonymic, naming a person's profession, generally in the Middle Ages; toponymic, naming the place where a person lived; or nicknames, comparing the person favourably or otherwise with the named animal.

History

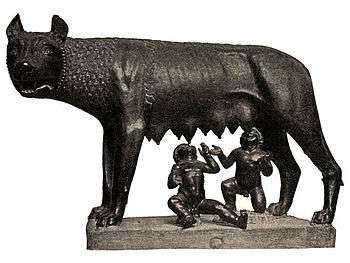

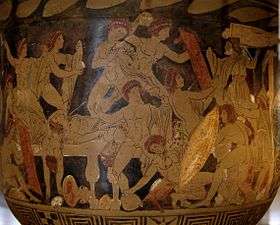

In the cultures of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, animal stereotypes grew until by the time of Virgil, animal epithets could be applied to anything from an abstract concept like love or fear, to a whole civilisation. An author could use an animal's name to emphasise a theme or to provide an overview of a complex epic tale. For example, Homer uses animal similes in the Iliad and the Odyssey, where the lion symbolises qualities such as bravery, leading up to the lion simile at the end of the Odyssey, where in Book 22 Odysseus kills all Penelope's suitors. In the Iliad, Homer compares the Trojans to stridulating grasshoppers, implying, suggests the classicist Gordon Lindsay Campbell, that they make a lot of noise but are weaker and less determined than they think. In the Aeneid, Book 4, Virgil compares the world of Dido, queen of Carthage, with a colony of ants. Dido's people are, argues Campbell, hardworking, strong, unfailingly loyal, organised, and self-regulating: just the sort of world that the hero Aeneas would like to create. But, Campbell suggests, the simile also suggests that Carthage's civilisation is fragile and insignificant, and could readily be destroyed.[1]

Insults

Animal epithets may be pejorative, indeed in some cultures highly offensive.[2] Epithets may however be used in political campaigns; in 1890, the trades unionist Chummy Fleming marched with a group of unemployed people through the streets of Melbourne, displaying a banner with the message "Feed on our flesh and blood you capitalist hyenas: it is your funeral feast".[3] On the other side of the ideological divide, the Cuban government described the revolutionary Che Guevara as a "communist rat" in 1958.[4]

Taboos

Edmund Leach argued in a classic 1964 paper that animal epithets are insulting when the animal in question is taboo, making its name suitable for use as an obscenity. For example, Leach argues that calling a person "a son of a bitch" or "you swine" means that the "animal name itself is credited with potency".[5]

In 1976, John Halverson argued that Leach's argument about taboos was "specious", and his "categorisation of animals in terms of 'social distance' and edibility is inconsistent in itself and corresponds neither to reality nor to the scheme of social distance and human sexuality it is claimed to parallel." Halverson disputed the association of animal epithets with potency, noting that calling a timid person a mouse, or a person who does not face reality an ostrich, or a silly person a goose, does not mean that these names are potent, taboo, or sacred.[6]

Timothy Jay argues, citing Leach, that the use of animal epithets as insults is partly down to taboos on eating pets or unfamiliar wild animals, and partly down to our stereotypes of animals' habits, such as that pigs "are dirty, fat, and eat filth." Jay further cites Sigmund Freud's view that obscenities that name animals, such as cow, cock, dog, pig, and bitch, gain their power by reducing people to animals.[7][8]

Metaphors and similes

The rat and the hyena are not the most common of what the linguistic researcher Aida Sakalauskaite calls "zoometaphors"[9] and Grzegorz A. Kleparski calls "zoosemy",[10][11] the use of metaphors from zoology. In each of three different languages, English, German, and Lithuanian, the most common animal categories are farmyard animals (40% in English), Canidae (including dog and wolf, 6% in English), and birds (10% in English). Grammatically, metaphor, as in "sly fox", is not the only option: speakers may also use simile, as in "deaf as an ass". In German, 92% of animal epithets are metaphors, 8% similes, whereas in English, 53% are similes, 47% metaphors.[9]

| Animal Group | Group frequency | Simile relative frequency | Simile examples | Metaphor relative frequency | Metaphor examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canidae | 13% | 49% | as hungry as a wolf; as friendly as a puppy | 51% | dog-tired; sly fox; vixen; bitch; dog; lone wolf |

| Birds | 13% | 35% | as black as a raven; to jabber like a bunch of blackbirds | 65% | to parrot; cuckoo; aquiline; to swan about; bird-brained; the vultures are circling; (warmaking) hawk versus (peacemaking) dove |

| Insects | 7% | 81% | as busy as a bee; to sting like a hornet | 19% | louse; cockroach; (inconstant) butterfly; (unfaithful [hopping from one partner to another]) grasshopper |

| Farmyard animals | 41% | 54% | as strong as an ox; to follow like a sheep; stubborn as a mule gentle as a lamb | 46% | to horse around; greedy pig; silly ass; a turkey (that will never fly); bovine; sheepish; mutton dressed as lamb |

| Other animals | 7% | 50% | as slow as a snail gruff as a bear | 50% | to ape; snake in the grass; speak with a forked tongue; snake; worm |

| Aquatic animals | 6% | 57% | flipping like a flounder; to swim like a fish | 43% | fishy; in shoals; (ugly) toad; (adaptable) chameleon; (small) shrimp |

| Cats | 8% | 40% | as brave as a lion | 60% | catty |

| Rodents[lower-alpha 1] | 5% | 62% | mad as a (March) hare; to fuck like a rabbit happy as a mouse in cheese/a pig in muck | 38% | frightened rabbit; squirrel/to squirrel away |

The Hungarian linguists Katalin Balogné Bérces and Zsuzsa Szamosfalvi found in a preliminary survey that the most commonly used "animal vocatives" were, in order, 1. pig, 2. chick(en), 3. dog/puppy, 4. cow, 5. monkey, 6. hen, 7. rat, 8. turkey, 9. mouse, 10. snake, 11. cat/kitten, 12. fox, 13. lamb, 14. vixen, 15. worm. Of these, using the classification devised by Sabina Halupka-Resetar, and Biljana Radic,[12] lamb was always used positively; cow and vixen referred to a person's appearance; pig indicated a person's eating habits; calling someone a fox or a turkey related to their intelligence, or lack of it; and names like cat, snake, worm, monkey, dog, mouse, chicken, lamb and rat were used to indicate a person's character.[13]

Surnames

Some English surnames from the Middle Ages name animals. These have different origins. Some, like Pigg (1066), Hogg (1079) and Hoggard, Hogarth (1279) are metonyms for a swineherd,[14] while Oxer (1327) similarly denotes an oxherd[15] and Shepherd (1279 onwards) means as it sounds a herder of sheep.[16]

Surnames that mention animals can also be toponymic, the names Horscroft, Horsfall, Horsley and Horstead for example all denoting people who came from these villages associated with horses. The surname Horseman (1226 onwards) on the other hand is a metonym for a rider, mounted warrior, or horse-dealer, while the surnames Horse and Horsnail could either be nicknames or metonyms for workers with horses and shoers of horses respectively.[17]

Some surnames, like Bird, dating from 1193 onwards, with variants like Byrd and Bride, are most likely nicknames for a birdlike person, though they may also be metonyms for a birdcatcher; but Birdwood is toponymic, for a person who lived by a wood full of birds.[18] Eagle from 1230 is a nickname from the bird,[19] while Weasel, Wessel from 1193 and Stagg from 1198 are certainly nicknames from those animals.[20] It is not always easy to tell whether a nickname was friendly, humorous or negative, but the surname Stallion, with variants Stallan, Stallen and Stallon, (1202 onwards) is certainly pejorative, meaning "a begetter, a man of lascivious life".[21]

Surnames behave in similar ways in other languages; for example in France, surnames can be toponymic, metonymic, or may record nicknames ("sobriquets"). Poisson (Fish) is a metonym for a fishmonger or fisherman.[22] Loiseau (The bird) and Lechat (The cat) are nicknames, Lechat indicating either a flexible man or a hypocrite, Loiseau suggesting a lightly-built birdlike person.[23][24] In Sweden, the surname Falk (Falcon) is common;[25] it is found among Swedish nobility from 1399.[26]

See also

Notes

- ↑ And lagomorphs, which were formerly counted as rodents.

References

- 1 2 Campbell, Gordon Lindsay (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 145–147, and passim. ISBN 978-0-19-103516-6.

- ↑ Herzfeld, Michael (2016). Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics and the Real Life of States, Societies, and Institutions. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-317-29755-0.

- ↑ Scates, Bruce (1997). A New Australia: Citizenship, Radicalism and the First Republic. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-521-57296-5.

- ↑ Reid-Henry, Simon (2009). Fidel and Che: A Revolutionary Friendship. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-84894-138-0.

- ↑ Leach, Edmund. Lenneberg, E. H., ed. Anthropological Aspects of Language: Animal Categories and Verbal Abuse. New directions in the study of language. MIT Press.

- ↑ Halverson, John (December 1976). "Animal Categories and Terms of Abuse". Man. 11 (4): 505–516. JSTOR 2800435. (Subscription required)

- ↑ Jay, Timothy (1999). Why We Curse: A neuro-psycho-social theory of speech. John Benjamins. pp. 196–. ISBN 978-90-272-9848-5.

- ↑ Murphy, Bróna (2010). Corpus and Sociolinguistics: Investigating age and gender in female talk. John Benjamins. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-90-272-8861-5.

- 1 2 3 Sakalauskaite, Aida (2010). Zoometaphors in English, German, and Lithuanian: A Corpus Study (PDF). University of California, Berkeley (PhD Thesis). Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ↑ Kleparski, G.A. (1990). Semantic Change in English: A Study of Evaluative Developments in the Domain of Humans. Wydawnictwo KUL.

- ↑ Kiełtyka, R. and G.A. Kleparski. 2005. “The scope of English zoosemy: the case of DOMESTICATED ANIMALS” [in:] Kleparski. G.A. (ed.). Studia Anglica Resoviensia 3, 76-87.

- ↑ Halupka-Resetar, Sabina; Radic, Biljana (2003). "Animal names used in addressing people in Serbian". Journal of Pragmatics. 35: 1891–1902.

- ↑ Bérces, Katalin Balogné; Szamosfalvi, Zsuzsa (28 January 2009). "Animal Names Used in Addressing People (in English)". Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ Reaney, pages 234, 351

- ↑ Reaney, page 334

- ↑ Reaney, pages 404–405

- ↑ Reaney, page 239

- ↑ Reaney, page 45

- ↑ Reaney, page 148

- ↑ Reaney, pages 423, 480

- ↑ Reaney, page 423

- ↑ "Patronyme Poisson : Nom de famille" (in French). Genealogie.com. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "Patronyme Lechat : Nom de famille" (in French). Genealogie.com. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "Patronyme Loiseau : Nom de famille" (in French). Genealogie.com. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "Efternamn, topp 100 (2015)" (in Swedish). Statistiska centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden). 22 February 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Hildebrand, Bengt. "Falck och Falk, släkter". Svenskt biografiskt lexikon. Riksarkivet (Swedish national archive). Retrieved 27 July 2016.

Sources

- Reaney, P. H.; Wilson, R. M. (1997). A Dictionary of English Surnames. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-198-60092-5.

.jpg)

_-_Farm_Animals%2C_Milking%2C_and_Buttermaking%3B_Zodiacal_Sign_of_Taurus_detail.jpg)