Naltrexone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Revia, Vivitrol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a685041 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular |

| ATC code | N07BB04 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 5–40% |

| Protein binding | 21% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Biological half-life |

4 h (naltrexone), 13 h (6β-naltrexol) |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

16590-41-3 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5360515 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 1639 |

| DrugBank |

DB00704 |

| ChemSpider |

4514524 |

| UNII |

5S6W795CQM |

| KEGG |

D05113 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:7465 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL19019 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

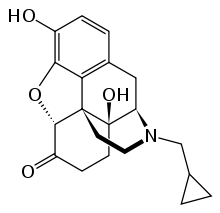

| Formula | C20H23NO4 |

| Molar mass | 341.401 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Melting point | 169 °C (336 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Naltrexone is a medication that reverses the effects of opioids and is used primarily in the management of alcohol dependence and opioid dependence.[1]

The closely related medication methylnaltrexone is used to treat opioid-induced constipation. Nalmefene is a very similar drug that is used for the same purposes as naltrexone. Naltrexone should not be confused with naloxone nor nalorphine, which are used in emergency cases of opioid overdose.

Naltrexone is marketed as its hydrochloride salt, naltrexone hydrochloride, under the trade names Revia and Depade. A once-monthly extended-release injectable formulation is marketed under the trade name Vivitrol. In the United States as of 2016, naltrexone tablets cost about $0.91 per day.[2][3] The extended-release injections cost about $1248.50 USD per month (41.62 USD per day).[2]

Medical uses

Alcoholism

The main use of naltrexone is for the treatment of alcoholism. Naltrexone has been shown to decrease heavy drinking, the number of days alcohol is drunk, and the total amount of alcohol consumed.[4] It does not appear to change the percentage of people drinking at all.[5] The overall benefit has been described as "modest".[6]

Acamprosate may work better than naltrexone for bringing about no drinking, while naltrexone may decrease the desire for alcohol to a greater extent.[7]

The Sinclair method is a method of using opiate antagonist such as naltrexone to treat alcoholism by having the person take the medication about an hour before they drink alcohol, and only then, in order to avoid side effects that arise from chronic use.[8][9] The opioid blocks the positive reinforcement effects of ethanol and hopefully allows the person to stop drinking or drink less.[9]

Opioid use disorder

Naltrexone helps patients overcome opioid addiction by blocking the effects of opioid drugs. It has little effect on opioid cravings.[10] Naltrexone has in general been better studied for alcoholism than in treating opioid addiction. It is also more frequently used for alcoholism, despite originally being approved by the FDA in 1984 for opioid addiction.[11]

A 2011 review of studies suggested that naltrexone when taken by mouth was not superior to placebo or to no medication, nor was it superior to benzodiazepine or buprenorphine. Because of the poor quality of the reviewed studies, the authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support naltrexone therapy when taken by mouth for an opioid use disorder.[12] While some patients do well with the oral formulation, there is a drawback in that it must be taken daily, and a patient whose cravings become overwhelming can obtain opioid intoxication simply by skipping a dose before resuming opioid use. Due to this issue, the usefulness of oral naltrexone in opioid use disorders is limited by the low retention in treatment. Oral naltrexone remains an ideal treatment only for a small part of the opioid-addicted population, usually the ones with an unusually stable social situation and motivation. With additional contingency management support naltrexone is effective in a broader population.[13]

Extended-release depot injections of naltrexone administered once per month have proven somewhat effective in treating opioid abuse, an approach that avoids the compliance issue that arises from the more frequent, easily skipped oral doses.[14]

Adverse effects

The most common side effects reported with naltrexone are non-specific gastrointestinal complaints such as diarrhea and abdominal cramping.

Naltrexone has been reported to cause liver damage (when given at doses higher than recommended). It carries an FDA boxed warning for this rare side effect. Due to these reports, some physicians may check liver function tests prior to starting naltrexone, and periodically thereafter. Concerns for liver toxicity initially arose from a study of non-addicted obese patients receiving 300 mg of naltrexone.[15] Subsequent studies have suggested limited toxicity in other patient populations.

Naltrexone should not be started until several (typically 7-10) days of abstinence from opioids has been achieved. This is due to the risk of acute opioid withdrawal if naltrexone is taken, as naltrexone will displace most opioids from their receptors. The time of abstinence may be shorter than 7 days, depending on the half-life of the specific opioid taken. Some physicians use a naloxone challenge to determine whether an individual has any opioids remaining. The challenge involves giving a test dose of naloxone and monitoring for opioid withdrawal. If withdrawal occurs, naltrexone should not be started.[11]

It is important that one not attempt to use opioids while using naltrexone. Although naltrexone blocks the opioid receptor, it is possible to override this blockade with very high doses of opioids. However this is quite dangerous and may lead to opioid overdose, respiratory depression, and death. Similarly one will not show normal response to opioid pain medications when taking naltrexone. In a supervised medical setting pain relief is possible but may require higher than usual doses, and the individual should be closely monitored for respiratory depression. All individuals taking naltrexone are encouraged to keep a card or a note in their wallet in case of an injury or another medical emergency. This is to let medical personnel know that special procedures are required if opiate-based painkillers are to be used.

There has been some controversy regarding the use of opioid-receptor antagonists, such as naltrexone, in the long-term management of opioid dependence due to the effect of these agents in sensitizing the opioid receptors. That is, after therapy, the opioid receptors continue to have increased sensitivity for a period during which the patient is at increased risk of opioid overdose. This effect reinforces the necessity of monitoring of therapy and provision of patient support measures by medical practitioners.

Contraindications

Naltrexone should not be used by persons with acute hepatitis or liver failure, or those with recent opioid use (typically 7–10 days).

Pharmacogenetics

A naltrexone treatment study by Anton et al., released by the National Institutes of Health in February 2008 and published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, has shown that alcoholics having a certain variant of the opioid receptor gene (G polymorphism of SNP Rs1799971 in the gene OPRM1), known as Asp40, demonstrated strong response to naltrexone and were far more likely to experience success at cutting back or discontinuing their alcohol intake altogether, while for those lacking the gene variant, naltrexone appeared to be no different from placebo.[16] The G allele of OPRM1 is most common in individuals of Asian descent, with 60% to 70% of people of Chinese, Japanese, and Indian ancestry having at least one copy, as opposed to 30% of Europeans and very few Africans.[17]

Because of the characteristics of the patient group in the US, the first study was done on white patients, and the next without regard for ethnicity. Anton et al. found that patients of African descent did not have much success with naltrexone in treatment for alcohol dependence because of lacking the relevant gene.[16]

As white patients with the gene had a five times greater rate of success in reducing drinking when given naltrexone than did patients without the gene, when used in a protocol of Medical Management (MM), Anton et al. concluded,

"Because almost 25% of the treatment-seeking population carries the Asp40 allele, genetic testing of individuals before naltrexone treatment might be worth the cost and effort, especially if structured behavioral treatment were not being considered."[16] This would enable treatment to be targeted by genetics to patients for whom it would be most effective. They noted, "Naltrexone is relatively easy to administer and free of serious adverse effects and, as we observed in the Asp40 carriers we studied, it appears to be highly effective."[16]

Studies have found naltrexone to be more efficacious among certain white subjects, because of the genetic basis, than among black subjects, who generally do not carry the relevant gene variant.[18] A 2009 study of naltrexone as an alcohol dependence treatment among African Americans failed to find any statistically significant differences between naltrexone and a placebo.[19] Studies have suggested that carriers of the G allele may experience higher levels of craving and stronger "high" upon alcohol consumption, compared to carriers of the dominant allele, and naltrexone somewhat blunts these responses, leading to a reduction in alcohol use in some studies.[20]

Mechanism of action

Naltrexone and its active metabolite 6β-naltrexol are antagonists at the μ-opioid receptor (MOR), the κ-opioid receptor (KOR) to a lesser extent, and to a far lesser and possibly insignificant extent, at the δ-opioid receptor (DOR).[21] The Ki affinity values of naltrexone at the MOR, KOR, and DOR have been reported as 0.0825 nM, 0.509 nM, and 8.02 nM, respectively, demonstrating a KOR/MOR binding ratio of 6.17 and a DOR/MOR binding ratio of 97.2.[22]

The blockade of opioid receptors is the basis behind naltrexone's action in the management of opioid dependence—it reversibly blocks or attenuates the effects of opioids. Its mechanism of action in alcohol dependence is not fully understood, but as an opioid receptor antagonist is likely to be due to the modulation of the dopaminergic mesolimbic pathway (one of the primary centers for risk-reward analysis in the brain, and a tertiary "pleasure center") which is hypothesized to be a major center of the reward associated with addiction that all major drugs of abuse are believed to activate. Mechanism of action may be antagonism to endogenous opiates such as tetrahydropapaveroline, whose production is augmented in the presence of alcohol.[23]

Structure and pharmacokinetics

Naltrexone can be described as a substituted oxymorphone – here the tertiary amine methyl-substituent is replaced with methylcyclopropane. Naltrexone is the N-cyclopropylmethyl derivative of oxymorphone.

Naltrexone is metabolized mainly to 6β-naltrexol by the liver enzyme dihydrodiol dehydrogenase. Other metabolites include 2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-6β-naltrexol and 2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-naltrexone. These are then further metabolised by conjugation with glucuronide.

The plasma half-life of naltrexone and its metabolite 6β-naltrexol are about 4 hours and 13 hours, respectively.

Formulations

A naltrexone formulation for depot injection was approved by the FDA on April 13, 2006 for the treatment of alcohol dependence.[24]

Additionally, naltrexone implants that are surgically implanted are available.[25] Naltrexone implants have been used successfully in Australia for a number of years as part of a long-term protocol for treating opiate addiction.[26]

Controversies

The FDA authorized use of injectable naltrexone for opioid addiction using a single study.[27] This study was run out of Russia, a country where opioid agonists such as methadone and buprenorphine are not available. Therefore, this single trial of naltrexone was performed not by comparing it to the best available, evidence-based treatment (methadone or buprenorphine) but by comparing it with a placebo.[28] In addition, the study failed to follow up on participants to document post-treatment overdose - a key measure for opioid substitution therapies.[29] These factors led to criticism of the study's design and ethics, and, by extension, of the FDA's approval of injectable naltrexone for opioid addiction based on this study.[30]

Research

Depersonalization/derealization

Naltrexone is sometimes used in the treatment of dissociative symptoms such as depersonalization and derealization.[31][32] Some studies suggest it might help.[33] Other small, preliminary studies have also shown benefit.[31][32] It is thought that blockade of the KOR by naltrexone and naloxone is responsible for their effectiveness in ameliorating depersonalization and derealization.[31][32] Since these drugs are less efficacious in blocking the KOR relative to the MOR, higher dose than typically used seem to be necessary.[31][32]

Low-dose naltrexone

"Low-dose naltrexone" (LDN) describes the "off-label" use of naltrexone at low doses for diseases not related to chemical dependency or intoxication, such as multiple sclerosis.[34] More research needs to be done before it can be recommended for clinical use.

Although there are scientific studies showing its efficacy in some conditions such as fibromyalgia,[35] other, more dramatic claims for its use in conditions like cancer and HIV have less scientific support.[34] This treatment has received significant attention on the Internet, especially through websites run by organizations promoting its use.[36]

Tobacco dependence

A study done by The Chicago Stop Smoking Research Project at the University of Chicago found that naltrexone did not help to improve a subject's chance of attaining smoking cessation when compared to a placebo.[37]

Self-injurious behaviors

Some studies suggest that self-injurious behaviors present in persons with developmental disabilities (including autism) can sometimes be remedied with naltrexone.[38] In these cases, it is believed that the self-injury is being done to release beta-endorphin, which binds to the same receptors as heroin and morphine.[39] If the "rush" generated by self-injury is removed, the behavior may stop.

Behavioral disorders

There are indications that naltrexone might be beneficial in the treatment of impulse control disorders such as kleptomania, compulsive gambling, or trichotillomania (compulsive hair pulling), but there is conflicting evidence of its effectiveness for gambling.[40][41][42] A 2008 case study reported successful use of naltrexone in suppressing and treating an internet pornography addiction.[43]

Countering adverse effects of interferon alpha

Naltrexone is effective in suppressing the cytokine type mediated adverse neuropsychiatric effects of interferon alpha therapy.[44][45]

See also

- Bupropion/naltrexone

- Nalmefene

- Nalodeine

- One Little Pill (2014 film) - documentary about using naltrexone to treat alcohol use disorder

- Samidorphan

- Buprenorphine/naltrexone

References

- ↑ C.R. Ganellin; David J. Triggle (21 November 1996). Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents. CRC Press. pp. 1396–. ISBN 978-0-412-46630-4.

- 1 2 "NADAC as of 2016-10-12 | Data.Medicaid.gov". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ↑ "Naltrexone". ATC/DDD Index. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

DDD ... 50 mg

- ↑ Rösner, S; Hackl-Herrwerth, A; Leucht, S; Vecchi, S; Srisurapanont, M; Soyka, M (8 December 2010). "Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (12): CD001867. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001867.pub2. PMID 21154349.

- ↑ Donoghue, K; Elzerbi, C; Saunders, R; Whittington, C; Pilling, S; Drummond, C (June 2015). "The efficacy of acamprosate and naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence, Europe versus the rest of the world: a meta-analysis.". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 110 (6): 920–30. doi:10.1111/add.12875. PMID 25664494.

- ↑ Garbutt, JC (2010). "Efficacy and tolerability of naltrexone in the management of alcohol dependence.". Current pharmaceutical design. 16 (19): 2091–7. doi:10.2174/138161210791516459. PMID 20482515.

- ↑ Maisel, NC; Blodgett, JC; Wilbourne, PL; Humphreys, K; Finney, JW (February 2013). "Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful?". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 108 (2): 275–93. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04054.x. PMC 3970823

. PMID 23075288.

. PMID 23075288. - ↑ Anderson, Kenneth (Jul 28, 2013). "Drink Your Way Sober with Naltrexone". Psychology Today. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- 1 2 Sinclair, JD (2001). "Evidence about the use of naltrexone and for different ways of using it in the treatment of alcoholism.". Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire). 36 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1093/alcalc/36.1.2. PMID 11139409.

- ↑ Dijkstra BA, De Jong CA, Bluschke SM, Krabbe PF, van der Staak CP (June 2007). "Does naltrexone affect craving in abstinent opioid-dependent patients?". Addict Biol. 12 (2): 176–82. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00067.x. PMID 17508990.

- 1 2 Galanter, Marc; Kleber, Herbert. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment, 4th Edition. ISBN 1585622761

- ↑ Minozzi S, Amato L, Vecchi S, Davoli M, Kirchmayer U, Verster A (2011). "Oral naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD001333. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001333.pub4. PMID 21491383.

- ↑ Johansson, BA; Berglund, M; Lindgren, A (2006). "Efficacy of maintenance treatment with naltrexone for opioid dependence: a meta-analytical review". Addiction. 101: 491–503. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01369.x. PMID 16548929.

- ↑ Comer, Sandra D.; Sullivan, Maria A.; Yu, Elmer; Rothenberg, Jami L.; Kleber, Herbert D.; Kampman, Kyle; Dackis, Charles; O’Brien, Charles P. (2006). "Injectable, Sustained-Release Naltrexone for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (2): 210. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.210. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ↑ Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson, RL, et al: Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. Reports of false-positive urinalysis results were found for the following formulary and nonprescription medications brompheniramine, bupropion, chlorpromazine, clomipramine, dextromethorphan, diphenhydramine, doxylamine, ibuprofen, naproxen, promethazine, quetiapine, quinolones (ofloxacin and gatifloxacin), ranitidine, sertraline, thioridazine, trazodone, venlafaxine, verapamil, and a nonprescription nasal inhaler. False-positive urinalysis results for amphetamine and methamphetamine were the most commonly reported. Problems of Drug Dependence, 1985 (NIDA Research Monograph 67). Edited by Harris LS. Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1986, pp 66–72

- 1 2 3 4 Anton R; Oroszi G; O’Malley S; Couper D; Swift R; Pettinati H; Goldman D (2008). "An Evaluation of Opioid Receptor (OPRM1) as a Predictor of Naltrexone Response in the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (2): 135–144. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.2.135. PMC 2666924

. PMID 18250251.

. PMID 18250251. - ↑ "Rs1799971 (SNPedia)".

- ↑ HR Kranzler; et al. (2001). "Efficacy of Naltrexone and Acamprosate for Alcoholism Treatment: A Meta‐Analysis". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 25: 1335–1341. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02356.x.

- ↑ Laura A. Ray; David W. Oslin (2009). "Naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol dependence among African Americans: Results from the COMBINE Study". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 105: 256–258. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.006.

- ↑ Laura A. Ray; et al. (March 2012). "The Role of the Asn40Asp Polymorphism of the Mu Opioid Receptor Gene (OPRM1) on Alcoholism Etiology and Treatment: A Critical Review". Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 36 (3): 385–94. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01633.x. PMC 3249007

. PMID 21895723.

. PMID 21895723. - ↑ Niciu, Mark J.; Arias, Albert J. (24 July 2013). "Targeted Opioid Receptor Antagonists in the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorders". CNS Drugs. 27 (10): 777–787. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0096-4. PMC 4600601

. PMID 23881605.

. PMID 23881605. - ↑ Codd EE, Shank RP, Schupsky JJ, Raffa RB (September 1995). "Serotonin and norepinephrine uptake inhibiting activity of centrally acting analgesics: structural determinants and role in antinociception". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 274 (3): 1263–70. PMID 7562497.

- ↑ Haber, Hanka; Roske, Irmgard; Rottmann, Matthias; Georgi, Monika; Melzig, Matthias F. (1996). "Alcohol induces formation of morphine precursors in the striatum of rats". Life Sciences. 60 (2): 79–89. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(96)00597-8. ISSN 0024-3205.

- ↑ "Alcoholism Once A Month Injectable Drug, Vivitrol, Approved By FDA," Medical News Today, April 16, 2006.

- ↑ Therapeutic Goods Administration. "Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods Medicines" (Online database of approved medicines). Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ↑ Hulse, Gary K.; Morris, Noella; Arnold-Reed, Diane; Tait, Robert J. (October 2009). "Improving Clinical Outcomes in Treating Heroin Dependence: Randomized, Controlled Trial of Oral or Implant Naltrexone". Archives of General Psychiatry. 66 (10): 1108–1115. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.130. PMID 19805701.

- ↑ http://www.psmag.com/health-and-behavior/vivitrol-help-control-addictions-57261

- ↑ http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(11)61333-0/fulltext

- ↑ https://www.med.upenn.edu/psych/documents/ADAW_050911.pdf

- ↑ http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2810%2962056-9/fulltext?rss=yes

- 1 2 3 4 Daphne Simeon; Jeffrey Abugel (10 October 2008). Feeling Unreal: Depersonalization Disorder and the Loss of the Self. Oxford University Press. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-0-19-976635-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Ulrich F. Lanius, PhD; Sandra L. Paulsen, PhD; Frank M. Corrigan, MD (13 May 2014). Neurobiology and Treatment of Traumatic Dissociation: Towards an Embodied Self. Springer Publishing Company. pp. 489–. ISBN 978-0-8261-0632-2.

- ↑ Sierra, M (January 2008). "Depersonalization disorder: pharmacological approaches.". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 8 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.1.19. PMID 18088198.

- 1 2 Novella, Steven (5 May 2010). "Low Dose Naltrexone – Bogus or Cutting Edge Science?". Science-Based Medicine. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Younger, Jarred (22 April 2009). "Fibromyalgia Symptoms are Reduced by Low-Dose Naltrexone: A Pilot Study". Pain Medicine. 10: 663–72. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00613.x. PMC 2891387

. PMID 19453963.

. PMID 19453963. - ↑ Bowling, Allen C. "Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) The "411" on LDN". National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ King A, de Wit H, Riley R, Cao D, Niaura R, Hatsukami D (2006). "Efficacy of naltrexone in smoking cessation: A preliminary study and an examination of sex differences". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 8 (5): 671–82. doi:10.1080/14622200600789767. PMID 17008194.

- ↑ Smith, Stanley G.; Gupta, Krishan K.; Smith, Sylvia H. (June 1995). "Effects of naltrexone on self-injury, stereotypy, and social behavior of adults with developmental disabilities". Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 7 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1007/BF02684958.

- ↑ Manley, Cynthia (1998-03-20). "Self-injuries may have biochemical base: study". The Reporter.

- ↑ Grant, J (2009-04-03). "Drug Suppresses The Compulsion To Steal, Study Shows". Science daily.

- ↑ "A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of concurrent alcohol dependence and pathological gambling"

- ↑ Suck Won Kim, Jon E Grant, David E Adson, Young Chul Shin, Double-blind naltrexone and placebo comparison study in the treatment of pathological gambling, Biological Psychiatry, Volume 49, Issue 11, 1 June 2001, Pages 914-921. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006322301010794)

- ↑ Bostwick, J. M. (2008-02-01). "Internet Sex Addiction Treated With Naltrexone". Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

- ↑ Vignau J, Karila L, Costisella O, Canva V (2005). "[Hepatitis C, interferon a and depression: main physiopathologic hypothesis]". Encephale (in French). 31 (3): 349–57. doi:10.1016/s0013-7006(05)82400-5. PMID 16142050.

- ↑ Małyszczak K, Inglot M, Pawłowski T, Czarnecki M, Rymer W, Kiejna A (2006). "[Neuropsychiatric symptoms related to interferon alpha]". Psychiatr. Pol. (in Polish). 40 (4): 787–97. PMID 17068950.