Sonnet 78

| Sonnet 78 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

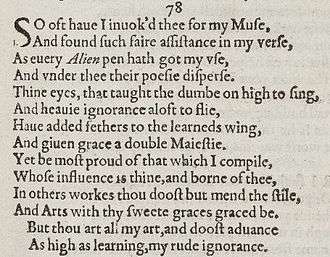

Sonnet 78 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 78 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It's a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man. Sonnet 78 marks the beginning of the Rival Poet sonnets.

Synopsis

The poet refers to the youth as his inspiration, comparing his own works to those of other poets, who have found in the youth creative inspiration for more traditional, learned forms of versifying. While other poets can add graces to their work by learning from the youth, the poet's work is completely defined by the youth's qualities.

Structure

Sonnet 78 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form, abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 5th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing (78.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The three quatrains describe how the poet feels that his muse has been his inspiration; no other poet can even come close to how much he values his muse. The couplet restates the idea of the muse being the poet's one and only art and the lifter of his ignorance.

Analysis

According to Helen Vendler, "Shakespeare excels in a form of verbal emphasis pointing up the conceptual oppositions of his verse."[2] He consistently operates through antithesis: "Antithesis is the rhetorical contrast of ideas by means of parallel arrangements of words, clauses, or sentences (as in "action, not words")" (Webster Dictionary). In this first poem of the Rival Poet sequence, "a firm antithesis is drawn between the putatively rude speaker and the other poets clustered round the young man."[2] They are all "learned" and practicing both art and style, while "the poor speaker's ignorance is twice insisted on, as is his muteness (he was dumb) before he saw the young man."[2]

The poem gives us directions as to how we should read it and which words we should emphasize: "The words of the couplet tie — art, high, learning [learnèd], ignorance — repeat in little the topics that are under dispute."[2]

Shakespeare likes to play with his words. This is especially evident in Sonnet 78. As Michael Schoenfeldt noted, "the more whimsical complimentary sonnets, such as 78… such sonnets may be fanciful, but they are not frivolous… Read from the right angle, so to speak, they can be very beautiful, or at least delightful; and in them, as elsewhere Shakespeare is inventing some game or other and playing it out to its conclusion in deft and surprising ways.[3]

The words "pen", "feather", and "style" — used in stanza 1, 2, and 3 respectively — seem to be related. The word pen comes from the Latin word penna meaning feather. The word style is derived from the Latin stilus meaning a writing instrument.[4] All three of these words have associations to the literary craft. As stated earlier, the word "pen" used in line has some sexual allusions as well.

The "dumb", "ignorance", "learned", and "grace" are nouns that occur in the second stanza. The words dumb and ignorance relate to the character of the poet as compared to his rivals, while "learned" and "grace" are qualities that describe his rivals.[4]

In line 7, the poet uses a "metaphor from falconry and refers to the practice of imping, engrafting extra feathers in the wing of a bird[4]" in order to improve the health and flight of the bird . Roy T. Eriksen suggests that there are some Italian allusions made in Sonnet 78. For example, he suggests that the phrase "penna d'ingegno" in Petrarch's sonnet 307, which means pen of genius, is "an analogue to Shakespeare's 'learned's wing'".[5] Referring to line 7, Eriksen says "Most editors comment on the image taken from falconry … that is the practice of mending a hawk's wing by imping feathers to it, but they all fail to notice its unmistakable Petrarchan metaphor".[5]

In line 10, where the poets speaks of something of "whose influence is thine" and is "born of thee", he uses a reproductive metaphor. Both of these refer to a parental influences on bringing up a child. In keeping with the theme for this sonnet, this child is the poem, and the parent or creator, is the fair youth.[4]

In line 12, Shakespeare repeats two words with the same root — "grace" and "graced", using a rhetorical style known as polyptoton. He does this in order to give more weight to his assertion shown in line 8 — where the word "grace " is again used to imply the power the muse has on the poet.[4]

In line 13, the phrase "thou art all my art" has been the subject of many discussions among scholars. The words art and art uses another rhetorical device known as antanaclasis, in which a word is used twice in different senses.[4] This use of the same words reemphasizes the claim of the poem that "the beloved's being and the speaker's art are one and the same thing", according to Stephen Booth.[4] Joel Fineman has another perspective on this well known phrase. He says, "Instead of 'thou art all my art', writing itself stands — not subtly, but explictiy —between the poet's first and second persons. Writing itself (the same writing written by "I" the poet and by the "thou" of the young man) gives the poet an ontological and poetic art of interference whose transference both is and is not what it is supposed to be"[6]

Context

Sonnet 78 we find out about a rival whose male and a poet and whose entry initiates an episode of jealousy that comes to a close in only Sonnet 86.[7] The rivalry between the poets may appear to be literary, but, according to the critic Joseph Pequigney, it is in reality a sexual rivalry. This is disturbing because the subject in the sonnet is one that the persona has found erotically profitable, in part because the other poet may be superior in learning and style. Shakespeare is not concerned with poetic triumph he is vying only for the prize of a fair friend. The combat between the two rivals is indirect and the speaker never addresses his literary adversary and only mentions his beloved. It is the body language of Sonnet 78 (the first in the series) 79, 80 and 84 that serves to convert the topic of letters into that of eroticism. Shakespeare is known for his usage of puns and double meaning on words. So it isn't surprising that he uses wordplay in the first quatrain on "pen" for the male appendage, or, as a Stein-cum-Joyce might say, "a pen is a penis a pen," is fully utilized. The poet remarks at 78.4, "every alien pen hath got my use," where "alien" = 'of a stranger' and "use," besides 'literary practice,' can = 'carnal enjoyment.'[7] These sexual allusions are made in passing; they are overtones, restricted to a line or two.

Debate in Sonnet 78

In Sonnet 78, Shakespeare has a mock debate between the young man and himself: "The mock-debate of the sonnet is: should the young man be prouder of Shakespeare's poem compiled out of rude ignorance, or of those of his more learned admirers?" This question is followed by a mock answer: "The mock answer is that the young man should be prouder of having taught a hitherto dumb admirer to sing, and of having advanced ignorance as high as learning, because these achievements on his part testify more impressively to his originally power than his (slighter) accomplishments with respect to his learned poets — he but mends their style and graces their arts." The debate that Shakespeare presents is "in a Petrarchan logical structure, with a clearly demarcated octave and sestet." Shakespeare has to exhibit his present art as at least equal to that of his rivals. He accomplishes this "by first resorting to a country-bumpkin, fairy-tale idiot-son role, presenting himself as a Cinderella, so to speak, raised from the cinders to the skies."[2] This is just an example of some of the ignorance that Shakespeare displays in parts of the sonnet such as in the first quatrain.

According to Helen Vendler,

The most interesting grammatical move in the poem is the use in Q2 of aspectual description: not "thou hast" as we would expect — to parallel the later "thou dost" and "thou art" — but thine eyes...have. The eyes govern the only four-line syntactic span (the rest of the poem is written in two-line units). We are made to pause for a two-line relative clause between thine eyes and its verb, have; in between subject and predicate we find ... the poet twice arising, once to sing, once to fly:

- Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing,

- And heavy ignorance aloft to fly,

- Have added...[2]

Vendler compares the speaker's praise of the young man (sonnet 78) to his praise of the mistress's eyes (sonnet 132): "The speaker's yearning aspectual praise of the young man's eyes is comparable to his praise of the mistress' eyes in 132 (Thine eyes i love) the difference between direct second-person pronominal address to the beloved and third-person aspectual description of one of the beloved's attributes is exploited here and in 132."[2]

Towards the end of the second quatrain, Vendler begins to question some of the metaphors and figurative language that Shakespeare has used: "Does the learned's wing need added feathers? Coming after the first soaring of the speak, the heavy added feathers and given grace seem phonetically leaden, while later the line arts with thy sweet graces graced by suggest that the learned verse has become surfeited with elaboration."[2] Another author, R.J.C. Wait, has a contrasting view of the learned wings. "The learneds wings represents another poet to whom Southampton has given inspiration."[8]

The last two lines of the sonnet is the couplet. Shakespeare starts with saying "but thou art my art." According to Vendler, "the phonetically and grammatically tautological pun — 'Thou art all my art ' — which conflates the copula and its predicate noun, enacts that plain mutual render, only me for thee (125) aspired to by the Sonnets and enacts as well the poet's simplicity contrasted with the affectations of the learned."[2] Once again, we see that Vendler is comparing and connecting sonnet 78 to another one of Shakespeare's sonnets, sonnet 125.

Rival Poet

- Main article: Rival Poet

"Shakespeare's sonnets 78-86 concern the Speaker's rivalry with other poets and especially with one 'better spirit' who is 'learned' and 'polished'".[9] In Sonnet 78 we find out about a rival who is male and a poet and whose entry initiates an episode of jealousy that comes to a close in only Sonnet 86[7] These sonnets are considered to be the Rival Poet sonnets. The rival poet sonnets include three primary players; the fair youth, the rival poet, and the lady who is desired by both men. The identities of these three players have been a controversy for hundreds of years and many experts disagree on the personage of the fair youth, rival poet, and lady.

The author Joseph Pequigney discusses the historic background of the rival poet, fair youth, and lady and states, "The rival poet referred to in Sonnet 78 to 86, (a) are wholly fictitious, or (b) are depictions of real but unknown persons, or (c) admit of historical identifications. In the case of (c) speculation centers mostly on the youth who is surmised to be either the earl of Southampton or the earl of Pembroke or, occasionally, some other nobleman. Marlowe and Chapman are the leading candidates for the role of the literary rival, the lady has generally fared less well in generating a historical counterpart. Regardless of whether the incidents and interpersonal transactions rendered are actual or imaginary, everything comes through as uncertain or indistinct because the Quarto, unauthorized and unsupervised by Shakespeare, (a) prints the Sonnets in a version to be understood as disarranged to a greater or lesser extent, or (b) the order of the poems in Q must be accepted in lieu of more satisfactory alternative, or (c) the lost original order may be reconstructed by acute transpositions.[7]" As with the fair youth there is some debate over the personage of the rival poet. Other experts disagree with Pequigney's assessment and another expert stated, "Among biographically minded commentators, a favourite candidate for Rival Poet has been Christopher Marlowe".[9]

The author R.J.C. Wait believes that the youth is none other than the Earl of Southampton. Waits states, "Shakespeare now clearly recognizes that Southampton is giving assistance to one or more rivals".[8] Another perspective is given by the author Macd. P. Jackson who states, "There can be no simple equation of a figure in Shakespeare's sonnets with a historical, biological personage.[8]" Waits argues that there are too many similarities for the fair youth to be anyone other than the Earl of Southampton, who was a known patron of the arts. The controversy around the identities of the fair youth, rival poet(s), and lady are an age old argument and may never be resolved as Shakespeare never explicitly identifies the individuals in the Sonnets.

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Vendler, Helen Hennessy. "78." The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard UP, 1998. 351. Print.

- ↑ "Strategies of Unfolding." Compassion to Shakespeare Sonnets. Ed. Michael Schoenfeldt. Malden: Blackwell Pub, 2007. 38. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Booth, Stephen. "Sonnet 78." Shakespeare's Sonnets: Edited with Anaylitic Commentary. Westford: Murray, 1977. Print

- 1 2 Eriksen, Roy T. "Extant And In Choice Italian: Possible Italian Echoes In Julius Caesar And Sonnet 78." English Studies 69.3 (1988): 224. Academic Search Complete. Web. 6 Feb. 2012.Eriksen, Roy T. "Extant And In Choice Italian: Possible Italian Echoes In Julius Caesar And Sonnet 78." English Studies 69.3 (1988): 224. Academic Search Complete. Web. 6 Feb. 2012.

- ↑ Fineman, Joel. Shakespeare's Perjured Eye: The Invention of Poetic Subjectivity in the Sonnets. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986

- 1 2 3 4 Pequigney, Joseph. "Jealous Thoughts." Such Is My Love: A Study of Shakespeare Sonnets. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1985. 103+. Print.

- 1 2 3 Wait, J. C. The Background to Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: Schocken, 1972. 78-80. Print.

- 1 2 Jackson, Mac.D P. "Francis Meres and the Cultural Contexts of Shakespeare's Rival Poet Sonnets." Review of English Studies 56.224 (APR 2005): 224-46. Print.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)