Republic of Ezo

| Republic of Ezo | ||||||||||

| 蝦夷共和国 | ||||||||||

| Secessionist state | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Location of Ezo | ||||||||||

| Capital | Hakodate | |||||||||

| Languages | Japanese, Ainu | |||||||||

| Government | Republic | |||||||||

| President | Enomoto Takeaki | |||||||||

| Vice President | Matsudaira Taro | |||||||||

| Historical era | Bakumatsu | |||||||||

| • | Established | January 27, 1869 | ||||||||

| • | Disestablished | June 27, 1869 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

The Republic of Ezo (蝦夷共和国 Ezo Kyōwakoku) was a short-lived state established in 1869 by former Tokugawa retainers in what is now known as Hokkaido, the large but sparsely populated northernmost island in modern Japan. Ezo is notable for being the first government to attempt to institute democracy in Japan.

Background

After the defeat of the forces of the Tokugawa shogunate in the Boshin War (1869) of the Meiji Restoration, a part of the former shogun's navy led by Admiral Enomoto Takeaki fled to the northern island of Ezo (now known as Hokkaido), together with several thousand soldiers and a handful of French military advisors and their leader, Jules Brunet. Enomoto made a last effort to petition the Imperial Court to be allowed to develop Hokkaido and maintain the traditions of the samurai unmolested, but his request was denied.[1]

Establishment of the Republic

On January 27, 1869 (New Style), the independent "Republic of Ezo" was proclaimed, with a government organization based on that of the United States, with Enomoto elected as its first president (sosai). Elections were based on universal suffrage among the samurai class.[2] This was the first election ever held in Japan, where a feudal structure under an Emperor with military warlords was the norm. Through Hakodate Magistrate Nagai Naoyuki, attempts were made to reach out to foreign legations present in Hakodate in order to obtain international diplomatic recognition.

The treasury included 180,000 gold ryō coins Enomoto retrieved from Osaka Castle following Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu's precipitous departure after the Battle of Toba-Fushimi in early 1868.[3]

During the winter of 1868-1869, the defenses around the southern peninsula of Hakodate were enhanced, with the star fortress of Goryōkaku at the center. The troops were organized under a joint Franco-Japanese command, commander-in-chief Ōtori Keisuke being seconded by the French captain Jules Brunet, and divided into four brigades, each commanded by a French officer (Fortant, Marlin, Cazeneuve and Bouffier). The brigades were themselves divided into two half-brigades each, under Japanese command.

Brunet demanded (and received) a signed personal pledge of loyalty from all officers and insisted they assimilate French ideas. An anonymous French officer wrote that Brunet had taken charge of everything:

| “ | ...customs, municipality, fortifications, army; everything passed through his hands. The simple Japanese are puppets whom he manipulates with great skill... he has carried out a veritable 1789 French Revolution in this brave new Japan; the election of leaders and the determination of rank by merit and not birth — these are fabulous things for this country, and he has been able to do things very well, considering the seriousness of the situation...[4] | ” |

Defeat by Imperial forces

Imperial troops soon consolidated their hold on mainland Japan, and in April 1869 dispatched a fleet and an infantry force of 7,000 men to Hokkaido. The Imperial forces progressed swiftly, won the Battle of Hakodate, and surrounded the fortress at Goryōkaku. Enomoto surrendered on June 26, 1869, turning the Goryōkaku over to Satsuma staff officer Kuroda Kiyotaka on June 27, 1869.[5] Kuroda is said to have been deeply impressed by Enomoto's dedication in combat, and is remembered as the one who spared the latter's life from execution. On September 20 of the same year, the island was given its present name, Hokkaido ("Northern Sea District").[5]

Perspectives

| Government officials | |

|---|---|

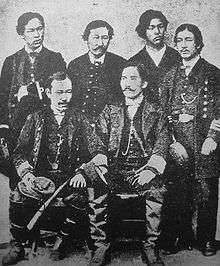

Leaders of the Republic of Ezo, with the President Enomoto Takeaki, front right (1869). | |

| President | Enomoto Takeaki |

| Vice-President | Matsudaira Taro |

| Navy Minister | Arai Ikunosuke |

| Army Minister | Ōtori Keisuke |

| Assistant Army Minister | Hijikata Toshizo |

| Hakodate Magistrate | Nagai Naoyuki |

| Assistant Hakodate Magistrate | Nakajima Saburosuke |

| Esashi Magistrate | Matsuoka Shirojiro |

| Assistant Esashi Magistrate | Kosugi Masanoshin |

| Matsumae Magistrate | Hitomi Katsutarō |

| Minister for Land Reclamation | Sawa Tarozaemon |

| Finance Minister | Enomoto Michiaki |

| Finance Minister | Kawamura Rokushiro |

| Commander of Warships | Koga Gengo |

| Infantry Commander | Furuya Sakuzaemon |

| Judge Advocate General Officer | Takenaka Shigekata |

| Judge Advocate General Officer | Imai Nobuo |

While later history texts were to refer to May 1869 as being when Enomoto accepted Emperor Meiji's rule, the Imperial rule was never in question for the Ezo Republic, as made evident by part of Enomoto's message to the Daijō-kan (太政官 Dajōkan) at the time of his arrival in Hakodate:

The farmers and merchants are unmolested, and live without fear, going their own way, and sympathising with us; so that already we have been able to bring some land into cultivation. We pray that this portion of the Empire may be conferred upon our late lord, Tokugawa Kamenosuke; and in that case, we shall repay your beneficence by our faithful guardianship of the northern gate.[6]

Thus from Enomoto's perspective, the efforts to establish a government in Hokkaido were not only for the sake of providing for the Tokugawa clan on the one hand (burdened as it was with an enormous amount of redundant retainers and employees), but also as developing Ezo for the sake of defense for the rest of Japan, something which had been a topic of concern for some time. Recent scholarship has noted that for centuries, Ezo was not considered a part of Japan the same way that the other "main" islands of modern Japan were, so the creation of the Ezo Republic, in a contemporary mindset, was not an act of secession, but rather of "bringing" the politico-social entity of "Japan" formally to Ezo.[7]

Enomoto was sentenced to a brief prison sentence, but was freed in 1872 and accepted a post as a government official in the newly renamed Hokkaido Land Agency. He later became ambassador to Russia, and held several ministerial positions in the Meiji Government.

Enomoto Takeaki, president.

Enomoto Takeaki, president. Otori Keisuke, Commander-in-Chief.

Otori Keisuke, Commander-in-Chief. Arai Ikunosuke, Commander of the Navy.

Arai Ikunosuke, Commander of the Navy. Hijikata Toshizo, Commander of the Shinsengumi.

Hijikata Toshizo, Commander of the Shinsengumi.

Notes

- ↑ Hillsborough, p. 4.

- ↑ Hübner, Joseph Alexander; Baroness Mary Elizabeth Herbert Herbert (1874). A Ramble Round the World, 1871: Japan. London: Macmillan. p. 138. Retrieved 2013-05-23. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthor=(help) - ↑ Onodera, 2004, p. 97.

- ↑ Sims, 1998.

- 1 2 Onodera, 2004, p. 196.

- ↑ Black, 1881, pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Suzuki, 1998, p. 32.

References

- Ballard C.B., Vice-Admiral G.A. The Influence of the Sea on the Political History of Japan. London: John Murray, 1921.

- Black, John R. Young Japan: Yokohama and Yedo, Vol. II. London: Trubner & Co., 1881.

- Hillsborough, Romulus (2005). Shinsengumi: The Shogun's Last Samurai Corps. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3627-2.

- Onodera Eikō, Boshin Nanboku Senso to Tohoku Seiken. Sendai: Kita no Sha, 2004.

- Sims, Richard. French Policy towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan 1854 - 1895, Richmond: Japan Library, 1998.

- Suzuki, Tessa Morris. Re-Inventing Japan: Time Space Nation. New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1998.

- Yamaguchi, Ken. Kinsé shiriaku A history of Japan, from the first visit of Commodore Perry in 1853 to the capture of Hakodate by the Mikado's forces in 1869. Trans. Sir Ernest Satow. Wilmington, Del., Scholarly Resources, 1973.

External links

Media related to Republic of Ezo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Republic of Ezo at Wikimedia Commons

Coordinates: 50°05′N 14°28′E / 50.083°N 14.467°E