Kuroda Kiyotaka

| Kuroda Kiyotaka | |

|---|---|

| 黑田 清隆 | |

| |

| 2nd Prime Minister of Japan | |

|

In office 31 August 1896 – 18 September 1896 Acting | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Itō Hirobumi |

| Succeeded by | Matsukata Masayoshi |

|

In office 30 April 1888 – 25 October 1889 | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Itō Hirobumi |

| Succeeded by | Sanjō Sanetomi (Acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

9 November 1840 Shinyashiki tōri-Chō, Japan |

| Died |

23 August 1900 (aged 59) Tokyo, Japan |

| Political party | Independent |

| Signature |

|

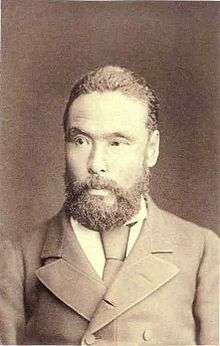

Count Kuroda Kiyotaka (黑田 清隆, November 9, 1840 – August 23, 1900), also known as Kuroda Ryōsuke (黑田 了介), was a Japanese politician of the Meiji era.[1] He was the second Prime Minister of Japan from April 30, 1888 to October 25, 1889.

Biography

As a Satsuma samurai

Kuroda was born to a samurai-class family serving the Shimazu daimyo of Kagoshima, Satsuma domain in Kyūshū.

In 1862, Kuroda was involved in the Namamugi Incident, in which Satsuma retainers killed a British national who refused to bow down to the daimyo's procession. This led to the Anglo-Satsuma War in 1863, in which Kuroda played an active role. Immediately after the war, he went to Edo where he studied gunnery.

Returning to Satsuma, Kuroda became an active member of the Satsuma-Chōshū joint effort to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate. Later, as a military leader in the Boshin War, he became famous for sparing the life of Enomoto Takeaki, who had stood against Kuroda's army at the Battle of Hakodate.

Political and Diplomatic Career

Under the new Meiji government, Kuroda became a pioneer-diplomat to Karafuto, claimed by both Japan and the Russian Empire in 1870. Terrified of Russia's push eastward, Kuroda returned to Tokyo and advocated quick development and settlement of Japan's northern frontier. In 1871 he traveled to Europe and the United States for five months, and upon returning to Japan in 1872, he was put in charge of colonization efforts in Hokkaidō.

In 1874, Kuroda was named director of the Hokkaidō Colonization Office, and organized a colonist-militia scheme to settle the island with unemployed ex-samurai and retired soldiers who would serve as both farmers and as a local militia. He was also promoted to lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army. Kuroda invited agricultural experts from overseas countries with a similar climate to visit Hokkaidō, and to provide advice on what crops and production methods might be successful.

Kuroda was dispatched as an envoy to Korea in 1875, and negotiated the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876. In 1877, he was sent as part of the force to suppress the Satsuma Rebellion. In 1878, he became de facto leader of Satsuma domain following the assassination of Ōkubo Toshimichi.

Shortly before he left office in Hokkaidō, Kuroda became the central figure in the Hokkaidō Colonization Office Scandal of 1881. As part of the government's privatization program, Kuroda attempted to sell the assets of the Hokkaidō Colonization Office to a trading consortium created by some of his former Satsuma colleagues for a nominal price. When the terms of the sale were leaked to the press, the resultant public outrage caused the sale to fall through. Also in 1881, Kuroda's wife died of a lung disease, but on rumors that Kuroda had killed her in a drunken rage, the body was exhumed and examined. Kuroda was cleared of charges, but rumors of his problems with alcohol abuse persisted.

In 1887, Kuroda was appointed to the cabinet post of Minister of Agriculture and Commerce.

Prime minister

Kuroda Kiyotaka became the 2nd Prime Minister of Japan, after Itō Hirobumi in 1888. During his term, he oversaw the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution. However, the vexing issue of Japan's inability to secure revision of the unequal treaties created considerable controversy. After drafts of proposed revisions drawn up his foreign minister Ōkuma Shigenobu became public in 1889, Kuroda was forced to resign.

Later life

Kuroda served as Minister of Communications in 1892 under the 2nd Ito Cabinet. In 1895 he became a genrō, and chairman of the Privy Council. Kuroda died of a brain hemorrhage in 1900 and Enomoto Takeaki presided over his funeral ceremonies. His grave is at the Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo.

Honours

From the corresponding Japanese Wikipedia article

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (May 11, 1877)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (August 1895)

- Count (July 1884)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (August 1900; posthumous)

See also

References

- ↑ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Kuroda Kiyotaka" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 578, p. 578, at Google Books.

Further reading

- Auslin, Michael R. (2006). Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01521-0; OCLC 56493769

- Jansen, Marius B. (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674003347; OCLC 44090600

- Keene, Donald. (2002). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12340-2; OCLC 46731178

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

- Sims, Richard L. (2001). Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation 1868–2000. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780312239145; ISBN 9780312239152; OCLC 45172740

External links

![]() Media related to Kiyotaka Kuroda at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kiyotaka Kuroda at Wikimedia Commons

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Hijikata Hisamoto |

Minister of Agriculture and Commerce 1887–1888 |

Succeeded by Inoue Kaoru |

| Preceded by Itō Hirobumi |

Prime Minister of Japan 1888–1889 |

Succeeded by Sanjō Sanetomi Acting |

| Preceded by Gotō Shōjirō |

Minister of Communications 1892–1895 |

Succeeded by Watanabe Kunitake |

| Preceded by Yamagata Aritomo |

Chairman of the Privy Council 1894–1900 |

Succeeded by Saionji Kinmochi |

| Preceded by Itō Hirobumi |

Prime Minister of Japan Acting 1896 |

Succeeded by Matsukata Masayoshi |