Shinsengumi

The Shinsengumi (新選組 or 新撰組, meaning "the new squad") was a special police force organized by the Bakufu (military government) during Japan's Bakumatsu period (late shogun) in 1864. It was active until 1869.[1] It was founded to protect the Shogunate representatives in Kyoto at a time when a controversial imperial edict to exclude foreign trade from Japan had been made and the Choshu clan had been forced from the imperial court. The men were drawn from the sword schools of Edo.[2] Although the Shinsengumi are lauded as brave and determined heroes in popular culture, they have been described by historians as a "ruthless murdering death squad".[3](p163)

History

Japan's forced opening to the west in 1854 (the choice to open its shores for trade or enter military conflict), exacerbated internal political instability. One long-standing line of political opinion was sonnō jōi (meaning, "revere the emperor, expel the barbarians").[4] Loyalists (particularly the Choshu clan) in Kyoto began to rebel. In response, the Tokugawa shogunate formed the Rōshigumi (浪士組, meaning "the rōnin squad") on October 19, 1863. The Roshigumi was a squad of 234 rōnin (Samurai without master) drawn from the sword schools of Edo.[5](p168)

The squad's nominal commander was the hatamoto Matsudaira Tadatoshi, and their leader was Kiyokawa Hachirō (a rōnin from Shonai Domain). The Roshigumi's mission was to protect Tokugawa Iemochi, the 14th shogun, during an important trip to Kyoto to meet with the Emperor Kōmei.[6](p65) There had not been such a meeting since the third shogun of the Tokugawa Bakufu, Tokugawa Iemitsu, had visited Kyoto in the 17th century. Tokugawa Iemochi, the head of the military government, the Bakufu, had been invited to discuss how Japan should enact the recent imperial edict calling for the expulsion of foreigners.[3](p186)

Although the Rōshigumi was funded by the Tokugawa government, the leader, Kiyokawa Hachirō and others had strong loyalties to the emperor and planned to gather other rōnin in Kyoto to police the city from insurgents. When Kiyokawa's scheme was revealed in Kyoto, they were forced to go back to Edo (Tokyo). But thirteen Rōshigumi members mainly from Mito clan remained and formed the Shinsengumi. The remaining members disbanded and then returned to Edo to form the Shinchōgumi (新徴組) under the patronage of the Shōnai domain.

Initially, the Shinsengumi were called Miburō (壬生浪), meaning "rōnin of Mibu". At the time, Mibu was a village south west of Kyoto, and was the place where the Shinsengumi were stationed. The Shinsengumi were led by Serizawa Kamo (b. 1830, Mino province), Kondō Isami (b. 1834, Musashi province – he came from a small dojo in Edo called Shieikan[7]) and Niimi Nishiki and initially formed three factions under Serizawa (the Mito group), Kondō (the Shieikan group) and Tonouchi. There were disagreements and tensions in the group: Kondo and Tonouchi killed Serizawa[5] and then Kondo killed Tonouchi on Yojou bridge. Serizawa had also ordered another member, Iesato Tsuguo, to commit seppuku for deserting. All this infighting left Kondo as leader.

Founding members:

- Serizawa's faction:

- Serizawa Kamo

- Niimi Nishiki

- Hirayama Gorō

- Hirama Jūsuke

- Noguchi Kenji

- Araya Shingorō

- Saeki Matasaburō

- Kondō's faction:

- Tonouchi's faction:

- Tonouchi Yoshio

- Iesato Tsuguo[6](p76)

- Abiru Aisaburō

- Negishi Yūzan

The Shinsengumi submitted a letter to the Aizu clan, another powerful group who supported the Tokugawa regime, requesting their permission to police Kyoto. The request was granted.

On September 30, 1865 (lunar calendar August 18), the Chōshū (anti-Tokugawa) clan were forced from the imperial court by the Tokugawa, Aizu and Satsuma clans. The Shinsengumi were sent to aid the Aizu and guard the gates of the imperial court. The new name "Shinsengumi" may have been coined by Matsudaira Katamori (the daimyō of the Aizu clan) around this time.[8] The opposition forces included the Mori clan of the Chōshū and the Shimazu clan of Satsuma.

In 1864, in an incident at the Ikedaya Inn, Kyoto, thirty Shinsengumi suppressed a cell of twenty Choshu revolutionaries, possibly preventing the burning of Kyoto. The incident made the squad more famous and led to soldiers enlisting in the squad.

Squad hierarchy after Ikedaya:

- Commander (局長 Kyokuchō): Kondō Isami, fourth master of the Tennen Rishin-ryū

- General Commander (総長 Sōchō): Yamanami Keisuke

- Vice Commander (副長 Fukuchō): Hijikata Toshizō

- Military Advisor (参謀 Sanbō): Itō Kashitarō

- Spies: Shimada Kai and Yamazaki Susumu.

Troop Captains (組長 Kumichō):

- Okita Sōji (instructor in Kenjutsu).

- Nagakura Shinpachi (instructor in Kenjutsu).

- Saitō Hajime (instructor in Kenjutsu).

- Matsubara Chūji (instructor in Jujitsu).

- Takeda Kanryūsai (instructor in military strategies).

- Inoue Genzaburō

- Tani Sanjūrō (instructor in spearing skills).

- Tōdō Heisuke

- Suzuki Mikisaburō

- Harada Sanosuke

In 1867, when Tokugawa Yoshinobu withdrew from Kyoto, the Shinsengumi left peacefully under the supervision of the wakadoshiyori, Nagai Naoyuki.[6](p172–174) The emperor Meiji had been named the head of a new government (meaning the end of over a century of military rule by the shoguns). This marked the beginning of the Boshin civil war.[5]

Following their departure from Kyoto, the Shinsengumi fought in the Battle of Toba-Fushimi.[6](p177) At Fushimi, Kondo suffered a gunshot wound but went on to fight at the Battle of Kōshū-Katsunuma. He was then captured in Nagareyama. After surrendering to imperial government forces, he was declared guilty of participation in the assassination of Sakamoto Ryōma and was beheaded in Itabashi three weeks later. Kondo was killed near Tokyo.[5]

The Shinsengumi fought in defense of Aizu territory under Saitō Hajime and joined the forces of the Republic of Ezo in the north.[6](p217–230) Shinsengumi numbers grew to over one hundred in this period and they fought on despite the fall of Edo and clear defeat of Tokugawa.[5] For example, Hijikata led a daring but doomed raid to steal the imperial warship, the Kotetsu. Hijikata's death from a gunshot wound on June 20 (lunar calendar May 11), 1869, in Hokkaido, marked the end of the Shinsengumi. Before his death, he wrote of his loyalty to the Tokugawa

- "Though my body may decay on the Island of Ezo,

- My spirit guards my lords in the East."

[9] Even so, another group of survivors, under Sōma Kazue, who had been under Nagai Naoyuki's supervision at Benten Daiba, surrendered separately,[6](p246) and a few core members, such as Nagakura Shinpachi, Saitō Hajime, and Shimada Kai, survived the war. Some members, such as Takagi Teisaku, went on to become prominent figures.[10]

Members of the group

At its peak, the Shinsengumi had about 300 members. They were the first samurai group of the Tokugawa era to allow those from non-samurai classes (farmers and merchants, for example) to join. Many joined the group due to the desire to become a samurai and be involved in political affairs. However, it is a misconception that most of the Shinsengumi members were from non-samurai classes. Out of 106 Shinsengumi members (among a total of 302 members at the time), there were 87 samurai, eight farmers, three merchants, three medical doctors, three priests, and two craftsmen. Several of the leaders, such as Yamanami, Okita, Saitō, Nagakura, and Harada, were born samurai.

Shinsengumi regulations

The code of the Shinsengumi included five articles, prohibiting deviation from the samurai code (Bushido), leaving the Shinsengumi, raising money privately, taking part in others' litigation, and engaging in private fights. The penalty for breaking any rule was seppuku. In addition, if the leader of a unit was mortally wounded in a fight, all the members of the unit must fight and die on the spot and, even in a fight where the death toll was high, the unit was not allowed to retrieve the bodies of the dead, except the corpse of the leader of the unit.

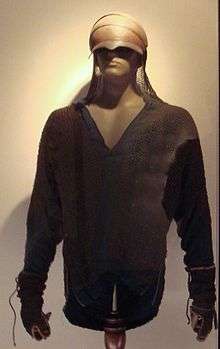

Uniform

The members of the Shinsengumi were highly visible in battle due to their distinctive uniforms. Following the orders of the Shinsengumi commander Serizawa Kamo, the standard uniform consisted of the haori and hakama over a kimono, with a white cord called a tasuki crossed over the chest and tied in the back. The function of the tasuki was to prevent the sleeves of the kimono from interfering with movement of the arms. The Shinsengumi wore a light chainmail suit beneath their robes and a light helmet made of iron[11] and a head band on which was inscribed the word, makoto (sincerity).[11]

The uniform was best defined by the haori, which was colored asagi-iro (浅葱色, light blue). The haori sleeves were trimmed with "white mountain stripes", resulting in a very distinctive uniform, quite unlike the usual browns, blacks, and greys found in warrior clothing.[12]

In popular culture

Shinsengumi are a staple of Japanese popular culture in general[12] and jidaigeki in particular.

The Shinsengumi have often been adapted in television drama, for example "Shinsengumi Shimatsuki" (Shinsengumi, its birth to end) (TBS, 1961); and "Shinsengumi Keppuroku" (NTV, 1967). In 2004, the Japanese television broadcaster NHK made a year-long television drama series following the history of the Shinsengumi, called Shinsengumi!, which aired on Sunday evenings.[13]

An early film, The Legend of Shinsengumi (1963) was based on a 1928 novel of the same name.[5] In 1969, a full-length film, Shinsengumi: Assassins of Honour, starring Toshiro Mifune was released.[14] It depicted the rise and fall of the Shinsengumi. The 1999 film, Taboo (Gohatto) depicted the Shinsengumi one year after the Ikedaya affair. The film shows the Shinsengumi's strict code and acceptance of homosexuality among the samurai members.[5] In 2003, a Japanese samurai drama, When the Last Sword Is Drawn, depicted the end of Shinsengumi, focusing on various historical figures such as Saitō Hajime.[15]

Manga artist Nobuhiro Watsuki is a self-proclaimed fan of the Shinsengumi and many of his characters in Rurouni Kenshin are based on its members, including Sagara Sanosuke (inspired by Harada Sanousuke); Shinomori Aoshi (modeled after Hijikata Toshizō); Seta Sōjirō (based on Okita Souji); and Saitō Hajime. The 2003 manga, Getsu Mei Sei Ki or Goodbye Shinsengumi by Kenji Morita depicted the life of Hijikata Toshizō. The manga Kaze Hikaru presents a fictional tale of a girl joining the Shinsengumi in disguise and falling in love with Okita Soji. The manga, Peacemaker Kurogane by Nanae Chrono is a historical fiction taking place during the end of the Tokugawa period, following a young boy, Ichimura Tetsunosuke, who tries to join the Shinsengumi. In Hideaki Sorachi's action-comedy manga, Gintama, the Shinsengumi (真選組) are popular characters. Their depiction however, being freely adapted for comedy purposes, was sometimes criticised for lacking historical precision. The anime series Soar High! Isami features three 5th graders who are fictional descendants of the Shinsengumi and they fight against the evil organization, the Black Goblin.

The game series/anime adaptation Hakuouki (The pale cherry blossom demons – or, the strange ballad of the shinsengumi) follows a girl, looking for her lost father (a doctor who worked with the Shinsengumi). The premise mixes supernatural elements and fictional enemies and historical events. The Shinsengumi characters are fictionalized adaptations of the real members and retain their real names throughout the show.[16]

The 2004 video game, Fu-un Shinsengumi which was developed by Genki and published by Konami is based on the Shinsengumi. In March 2012, the stand-alone expansion for Total War Shogun 2, Fall of the Samurai features the Shinsengumi as recruitable agents used for assassination and bribery, and as an elite combat unit capable of fighting both at range and in melee.

A popular Los Angeles-based Japanese restaurant, Shen-Sen-Gumi,[17] sells hakata-style ramen, with no association to the historical "ruthless murdering death squad" description.

The comedy anime Gintama, or Silver Soul, has several characters based on the Shinsengumi, and even the group themselves. Gintama tends to favour Hijikata Toushiro 'The Demon'/'Mayo Loving Freak' Kondo, 'the Gorilla' Okita Sougo, 'the Sadist'.

See also

Further reading

- Hillsborough R. Shinsengumi: the Shogun's last samurai corps. 2005 ISBN 0-8048-3627-2.

- Hillsborough R. Samurai sketches: from the bloody final years of the shogun. 2001 ISBN 0-9667401-8-1

- Kikuchi A. 菊地明 and Aikawa T. 相川司. Shinsengumi Jitsuroku 新選組実錄." Chikuma-shobō 筑摩書房, Tokyo 1996.

- Ōishi M. 大石学. Shinsengumi: Saigo no Bushi no Jitsuzō 新選組:最後の武士」の実像. Chūōkōron-shinsha 中央公論新社, Tokyo, 2004.

- Sasaki S. 佐々木克. Boshin sensō: Haisha no Meiji ishin 戊辰戦争 : 敗者の明治維新. Chūōkōron-shinsha 中央公論社, Tokyo,1977.

References

- ↑ Watsuki, N. "Glossary of the Restoration." Rurouni Kenshin Volume 3. Viz Media p190.

- ↑ Hurst G. and Hurst I. "Armed martial arts of Japan: swordsmanship and archery." Yale University Press 1998 p95. ISBN 9780300116748.

- 1 2 Turnbull S. "The Samurai swordsman – master of war." Tuttle Publishing, 2013 ISBN 1462908349, 9781462908349.

- ↑ Wakabayashi B. T. Anti-foreignism and Western learning in early-modern Japan: the new theses of 1825. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1986.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dougill J. "Kyoto: a cultural history." Oxford University Press, 2006 p171. ISBN 0195301374, 9780195301373.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Oishi M. Shinsengumi: Saigo no Bushi no Jitsuzō. Shin Jinbutsu Oraisha, Tokyo, 2004.

- ↑ Tokeshi J. "Kendo: rules and philosophy." University of Hawaii Press, 2003 p227 ISBN 0824825985, 9780824825980.

- ↑ "Bessengumi" An argument for Matsudaira Katamori bestowing the name can be made by comparing the similarity of the name "Shinsengumi" to one of Aizu's later frontline combat units, the Bessengumi (別選組, the "Separately Selected Corps").

- ↑ Clements J. "A brief history of the samurai." Constable & Robinson, 2013 ISBN 1472107721, 9781472107725.

- ↑ "Takagi became a professor of economics at Hitotsubashi University." Kuwana city website.

- 1 2 Turnbull S. "Katana: the samurai sword." Osprey Publishing, 2011 ISBN 1849086583, 9781849086585.

- 1 2 Zwier L. and Cunnungham M. "The End of the Shoguns and the birth of modern Japan (Pivotal moments in history series)." Twenty-First Century Books, revised edition, 2013 p63 ISBN 146770377X, 9781467703772.

- ↑ 新選組! NHK website.

- ↑ "Shinsengumi: Assassins of Honour IMDB website.

- ↑ "When the last sword is drawn." IMDB website

- ↑ Kapell M. and Elliot A. (ed.)"Playing with the past: digital games and the simulation of history." A&C Black, 2013 p140 ISBN 1623563879, 9781623563875.

- ↑ "Home | Best Japanese Restaurant Los Angeles - Shin-Sen-Gumi". www.shinsengumigroup.com. Retrieved 2016-06-24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shinsengumi. |

- Shinsengumi Headquarters Website created to address the needs of those who are interested in the history, related film/TV/anime, fanfiction, fanart and various incarnations of the Shinsengumi.

- Hajimenokizu A site dedicated to Saitou Hajime and the Shinsengumi in various fictional and historical incarnations.

- Samurai archives – Shinsengumi.