Pointe du Hoc

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pointe du Hoc (French pronunciation: [pwɛ̃t dy ɔk]) is a promontory with a 100 ft (30 m) cliff overlooking the English Channel on the coast of Normandy in northern France. During World War II it was the highest point between Utah Beach to the west and Omaha Beach to the east. The German army fortified the area with concrete casemates and gun pits. On D-Day (6 June 1944) the United States Army Ranger Assault Group assaulted and captured Pointe du Hoc after scaling the cliffs.

Background

Pointe du Hoc lies 4 mi (6.4 km) west of the center of Omaha Beach.[2][3] As part of the Atlantic Wall fortifications, the prominent cliff top location was fortified by the Germans. The battery was initially built in 1943 to house six captured French First World War vintage GPF 155mm K418(f) guns positioned in open concrete gun pits. The battery was occupied by the 2nd Battery of Army Coastal Artillery Regiment 1260 (2/HKAA.1260).[4] To defend the promontory from attack, elements of the 352nd Infantry Division were stationed at the battery.

Prelude

To provide increased defensive capability, the Germans began to improve the defenses of the battery in the spring of 1944, with enclosed H671 concrete casemates. The plan was to build six casemates but two were unfinished when the location was attacked. The casemates were built over and in front of the circular gun pits, which housed the 155mm guns. Also built was a H636 observation bunker and L409a mounts for 20mm Flak 30 anti-aircraft guns. The 155mm guns would have threatened the Allied landings on Omaha and Utah beaches when finished, risking heavy casualties to the landing forces.

The location was bombed in April 1944, after which the Germans removed the 155mm guns. During preparation for Operation Overlord it was determined that Pointe du Hoc should be attacked by ground forces, to prevent the Germans using the casemates for observation. The U.S. 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions were given the task of assaulting the strong point early on D-Day. Elements of the 2nd Battalion went in to attack Pointe du Hoc but delays meant the remainder of the 2nd Battalion and the complete 5th Battalion landed at Omaha Beach as their secondary landing position.

Though the Germans had removed the main armament from Pointe du Hoc, the beachheads were shelled from the nearby Maisy battery. The rediscovery of the battery at Maisy has shown that it was responsible for firing on the Allied beachheads until June 9, 1944.[5][6]

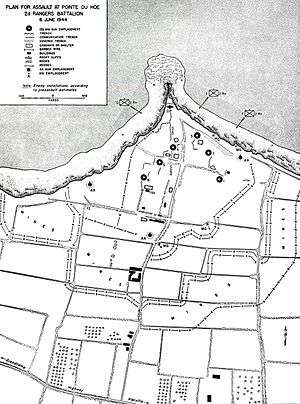

Plan

Pointe du Hoc lay within the General Leonard Gerow's V Corps field of operations. This then went to the 1st Infantry Division (the Big Red One) and then down to the right-hand assault formation, the 116th Infantry Regiment attached from 29th Division. In addition they were given two Ranger battalions to undertake the attack.

The Ranger battalions were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder. The plan called for the three companies of Rangers to be landed by sea at the foot of the cliffs, scale them using ropes, ladders, and grapples whilst under enemy fire, and engage the enemy at the top of the cliff. This was to be carried out before the main landings. The Rangers trained for the cliff assault on the Isle of Wight, under the direction of British Commandos.

Major Cleveland A. Lytle was to command Companies D, E and F of the 2nd Ranger Battalion (known as "Force A") in the assault at Pointe du Hoc. During a briefing aboard the Landing Ship Infantry TSS Ben My Chree he heard that Free French Forces sources reported the guns had not been removed. Impelled to some degree by alcohol,[7] Lytle became quite vocal that the assault would be unnecessary and suicidal and was relieved of his command at the last minute by Provisional Ranger Force commander Rudder. Rudder felt that Lytle could not convincingly lead a force with a mission that he did not believe in.[8] Lytle was later transferred to the 90th Infantry Division where he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.[9]

Battle

Landings

The assault force was carried in ten landing craft, with another two carrying supplies and four DUKW amphibious trucks carrying the 100 ft (30 m) ladders requisitioned from the London Fire Brigade. One landing craft carrying troops sank, drowning all but one of its occupants; another was swamped. One supply craft sank and the other put the stores overboard to stay afloat. German fire sank one of the DUKWs. Once within a mile of the shore, German mortars and machine guns fired on the craft.[10]

These initial setbacks resulted in a 40-minute delay in landing at the base of the cliffs, but British landing craft carrying the Rangers finally reached the base of the cliffs at 7:10am with approximately half the force it started out with. The landing craft were fitted with rocket launchers to fire grapnels and ropes up the cliffs. As the Rangers scaled the cliffs the Allied destroyers USS Satterlee and HMS Talybont provided them with fire support and ensured that the German defenders above could not fire down on the assaulting troops.[11] The cliffs proved to be higher than the ladders could reach.

Attack

The original plans had also called for an additional, larger Ranger force of eight companies (Companies A and B of the 2nd Ranger Battalion and the entire 5th Ranger Battalion) to follow the first attack, if successful. Flares from the cliff tops were to signal this second wave to join the attack, but because of the delayed landing, the signal came too late, and the other Rangers landed on Omaha instead of Pointe du Hoc. The added impetus these 500 plus Rangers provided on the stalled Omaha Beach landing has been conjectured to have averted a disastrous failure there, since they carried the assault beyond the beach, into the overlooking bluffs and outflanked the German defenses.

The force at the top of the cliffs also found that their radios were ineffective.[12] Upon reaching the fortifications, most of the Rangers learned for the first time that the main objective of the assault, the artillery battery, had been removed. The Rangers regrouped at the top of the cliffs, and a small patrol went off in search of the guns. Two different patrols found five of the six guns nearby (the sixth was being fixed elsewhere) and destroyed their firing mechanisms with thermite grenades.[7]

German counter-attacks

The costliest part of the battle for Pointe du Hoc for the Rangers came after the successful cliff assault. Determined to hold the vital high ground, yet isolated from other Allied forces, the Rangers fended off several counter-attacks from the German 914th Grenadier Regiment. The 5th Ranger Battalion and elements of the 116th Infantry Regiment headed towards Pointe du Hoc from Omaha Beach. However, only twenty-three Rangers from the 5th were able to link up with the 2nd Rangers during the evening of 6 June 1944. During the night the Germans forced the Rangers into a smaller enclave along the cliff, and some were taken prisoner.[6]:84-140

It was not until the morning of 8 June that the Rangers at Pointe du Hoc were finally relieved by the 2nd and 5th Rangers, plus the 1st Battalion of the 116th Infantry, accompanied by tanks from the 743rd Tank Battalion.[6]:133-134

Aftermath

Casualties

At the end of the two-day action, the initial Ranger landing force of 225+ was reduced to about 90 fighting men.[13][14] In the aftermath of the battle, some Rangers became convinced that French civilians had taken part in the fighting on the German side. A number of French civilians accused of shooting at American forces or of serving as artillery observers for the Germans were executed.[15]

Timeline

- 6 June 1944

.jpg)

06.39 – H-Hour – D, E and F companies of 2nd Ranger Battalion approach the Normandy coast in a flotilla of twelve craft.

07.05 – Strong tides and navigation errors mean the initial assault arrives late and the 5th Ranger Battalion as well A and B companies from 2nd Battalion move to Omaha Beach instead.

07.30 – Rangers fight their way up the cliff and reach the top and start engaging the Germans across the battery. Rangers discover the casemates are empty.

08.15 – Approximately 35 Rangers achieving the secondary objective of building a roadblock.

09.00 – Six German guns are located and destroyed using thermite charges.

For the rest of the day the Rangers repel several German counter-attacks. During the evening, one patrol from the Rangers that landed at Omaha beach make it through to join the Rangers at Pointe du Hoc.

- 7 June 1944

The Rangers continue to defend an even smaller area on Pointe du Hoc against German counter-attacks.

Afternoon – A platoon of Rangers arrives on an LST, with wounded removed.

- 8 June 1944

Morning – The Rangers are relieved by troops arriving from Omaha beach.

Commemoration

Pointe du Hoc now features a memorial and museum dedicated to the battle. Many of the original fortifications have been left in place and the site remains speckled with a number of bomb craters. On 11 January 1979 this 13-hectare field was transferred to American control, and the American Battle Monuments Commission was made responsible for its maintenance.[16]

Part of the modern day site, with the remains of a gun pit in the foreground.

Part of the modern day site, with the remains of a gun pit in the foreground. Pointe du Hoc, modern view, seen from the south-east.

Pointe du Hoc, modern view, seen from the south-east.- Present day view of the cliff of Pointe du Hoc with the monument on the top-right.

US President Ronald Reagan giving a speech commemorating the 40th anniversary of the event.

US President Ronald Reagan giving a speech commemorating the 40th anniversary of the event.

Media

The movie, The Longest Day (1962) depicts the assault and capture of Pointe du Hoc.

The assault on Pointe du Hoc has been portrayed in the 2005 video game Call of Duty 2, in which the player is a member of the Dog Company, 2nd Ranger Battalion, and is faced with destroying the artillery battery and fending off the counter-attacks.[17]

Pointe du Hoc is a map in the Battlefield 2 modification, Forgotten Hope 2.[18]

Pointe du Hoc is also a map in the strategy game Company of Heroes.

In the original script of Saving Private Ryan, Miller and his men landed at Pointe du Hoc, however this was scrapped and they landed at Omaha Beach instead.

References

- ↑ Zaloga (2009) p.50

- ↑ Heinz W.C. When We Were One: Stories of World War II, Basic Books, 2003, ISBN 978-0-306-81208-8, p170

- ↑ Le Cacheux, G. and Quellien J. Dictionnaire de la libération du nord-ouest de la France, C. Corlet, 1994, ISBN 978-2-85480-475-1, p289

- ↑ Zaloga, Steven. D-Day Fortifications in Normandy. Osprey Publications. ISBN 9781841768762.

- ↑ http://www.maisybattery.com The Maisy Battery

- 1 2 3 Sterne, Gary (2014). The Cover-up at Omaha Beach. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 286. ISBN 9781629143279.

- 1 2 American Battle Monuments Commission. "The Battle of Pointe du Hoc (interactive multimedia presentation)". ABMC website. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ↑ p.210 Gawne, Jonathan Spearheading D-Day: American Special Units 6 June 1944 2001 History and Collections

- ↑ LTC Cleveland Lytle, U.S.A. "Distinguished Service Cross Recipients". Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ↑ "The Ultimate Sacrifice: Rudder's Rangers at Pointe-du-Hoc" militaryhistoryonline.com

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. "D-Day: The Battle for Normandy". (2009) pp. 102–103

- ↑ Beevor, p. 103

- ↑ Bahmanyar, Mir (2006). Shadow Warriors: a History of the US Army Rangers. Osprey Publishing. pp. 48–49. ISBN 1-84603-142-7.

- ↑ Piehler, G. Kurt (2010). The United States and the Second World War: New Perspectives on Diplomacy, War, and the Home Front. Fordham University Press. p. 161. ISBN 0-8232-3120-8.

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. "D-Day: The Battle for Normandy". (New York: Penguin, 2009), p. 106

- ↑ "The American Battle Monuments Commission". Retrieved 29 October 2012.

The site, preserved since the war by the French Committee of the Pointe du Hoc, which erected an impressive granite monument at the edge of the cliff, was transferred to American control by formal agreement between the two governments on 11 January 1979 in Paris, with Ambassador Arthur A. Hartman signing for the United States and Secretary of State for Veterans Affairs Maurice Plantier signing for France.

- ↑ "Call of Duty 2 Review". Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ http://forgottenhope.warumdarum.de/fh2_maps.php?map=18

Further reading

- Anon (1946). "Pointe Du Hoe 2d Ranger Battalion 6 June 1944". Small Unit Actions (CMH Pub 100-14). American Forces in Action (United States Army Center of Military History 1991 ed.). Washington, DC: Historical Division, War Dept. OCLC 14207588.

- Harrison, G. A. (1951). Cross-Channel Attack (PDF). United States Army in World War II: The European Theater of Operations. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 606012173. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- O'Donnell, P. K. (2012). Dog Company: the Boys of Pointe Du Hoc: the Rangers Who Accomplished D-Day's Toughest Mission and Led the Way Across Europe. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-30682-029-8.

- Zaloga, S. J. (2009). Rangers Lead The Way, Pointe-du-Hoc D-Day 1944. Raid. 1. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-394-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pointe du Hoc. |

- Author Interview, November 15, 2012 Pritzker Military Library

- American D-Day: Omaha Beach, Utah Beach & Pointe du Hoc

- D-Day - Etat des Lieux: Pointe du Hoc

- President Reagan's speech at the 40th anniversary commemoration

- Ranger Monument on the American Battle Monuments Commission web site

- The World War II US Army Rangers celebrate the 50th Anniversary of D-Day

- Migraction.net: seawatching at Pointe du Hoc - for visitors interested in sea birds at this site

Coordinates: 49°23′45″N 0°59′20″W / 49.39583°N 0.98889°W