Operation Tractable

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Operation Tractable was the final offensive conducted by Canadian and Polish troops, supported by one brigade of British tanks, as part of the Battle of Normandy during World War II. The goal of this operation was to capture the strategically important French town of Falaise and then the smaller towns of Trun and Chambois. This operation was undertaken by the 1st Polish Armoured Division and the First Canadian Army against Army Group B of the Wehrmacht as part of the largest encirclement on the Western Front during the Second World War. Despite a slow start and limited gains north of Falaise, novel tactics by the 1st Polish Armoured Division—under the command of Generał brygady Stanisław Maczek during the drive for Chambois—enabled the Falaise Gap to be partially closed by 19 August 1944, trapping about 150,000 German soldiers in the Falaise Pocket.

Although the Falaise Gap was narrowed to a distance of several hundred yards, attacks and counter-attacks by two battle groups of the 1st Polish Armoured Division and the II SS Panzer Corps on Hill 262 (Mont Ormel) prevented the quick closing of the gap and thousands of German troops escaped. During two days of nearly continuous fighting, Polish forces using artillery barrages and close-quarter fighting, managed to hold off counter-attacks by seven German divisions. On 21 August, elements of the First Canadian Army relieved the Polish survivors and sealed the Falaise Pocket by linking up with the Third US Army. This led to the surrender and capture of the remaining units of the German 7th Army in the pocket.

Background

Following break-out by the US 1st and 3rd Armies from the beachhead during the Battle of Normandy after Operation Cobra on 25 July 1944, Adolf Hitler ordered an immediate counterattack against Allied forces in the form of Operation Lüttich. Lieutenant General Omar Bradley—the commanding general of the US 12th Army Group—was notified of the counterattack in advance through signals intercepted via Ultra radio intercepts and deciphering and thus prepared his troops and their commanders to defeat this counteroffensive and to encircle as much of the Wehrmacht force as possible.[2] By the afternoon of 7 August, Operation Lüttich had been defeated by concerted, large-scale fighter-bomber air strikes against the German Panzers and trucks. In the process, forces of the German 7th Army became further enveloped by the Allied advance out of Normandy.[2]

Following these failed German offensives, the town of Falaise became a major objective of Commonwealth forces, since its capture would cut off virtually all of Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge's Army Group B.[3] To achieve this, General Harry Crerar, commanding the newly formed Canadian 1st Army and Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds—commanding the Canadian II Corps, planned an Anglo-Canadian offensive with the code name of Operation Totalize. This offensive was designed to break through the defences in the Anglo-Canadian sector of the Normandy front.[4] Operation Totalize would rely on an unusual night attack using heavy bombers and the new Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers to achieve a breakthrough of German defences. Despite initial gains on Verrières Ridge and near Cintheaux, the Canadian Army's offensive stalled on 9 August, with strong Wehrmacht counterattacks resulting in heavy casualties for the Canadian and Polish armoured and infantry divisions.[5] By 10 August, Canadian troops had reached Hill 195, north of Falaise. They were unable to advance farther immediately and they had been unable to capture Falaise.[5]

Prelude

Offensive strategy

Operation Tractable incorporated lessons learned from Operation Totalize, notably the effectiveness of mechanized infantry units and tactical bombing raids by heavy bombers.[6] Unlike the previous operation, Tractable was launched in daylight. An initial bombing raid was to weaken German defences and was to be followed by an advance by the Canadian 4th Armoured Division on the western flank of Hill 195, while the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division attacked on the eastern flank with the Canadian 2nd Armoured Brigade in support. Their advance would be protected by a large smokescreen laid down by Canadian artillery.[6] Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery hoped that Canadian forces would achieve control of Falaise by midnight on August 14. From there, all three formations would advance towards Trun, 18 kilometres (11 mi) east of Falaise, with the additional assistance of the Polish 1st Armoured Division, numbering approximately 10,000 men.[7] Once in Trun, a linkup with the American 3rd Army at Chambois could be quickly accomplished.[8]

The main opposition to Simonds's force was the 12th SS Panzer Division, which included the remnants of two infantry divisions. German forces within the Falaise Pocket approached 350,000 men.[9] Had surprise been achieved, the Canadians would likely have succeeded in a rapid break-through.[10] However, on the night of 13/14 August, a Canadian officer lost his way while moving between divisional headquarters. He drove into German lines and was promptly killed. The Germans discovered a copy of Simonds' orders on his body.[6] As a result, the 12th SS Panzer Division placed the bulk of its remaining strength—500 grenadiers and 15 tanks, along with twelve 8.8 cm PaK 43 anti-tank guns—[11] along the Allies' expected line of approach.[6]

Battle

Initial drive for Falaise

Operation Tractable began at 12:00 on 14 August, when 800 Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax heavy bombers of RAF Bomber Command struck German positions along the front.[6] As with Totalize, many of the bombers mistakenly dropped their bombs short of their targets, causing 400 Polish and Canadian casualties.[6] Covered by a smoke screen laid down by their artillery, two Canadian divisions moved forwards.[6] Although their line of sight was reduced, German units still managed to inflict severe casualties on the Canadian 4th Armoured Division, which included its Armoured Brigade commander Brigadier Leslie Booth, as the division moved south toward Falaise.[6] Throughout the day, continual attacks by the Canadian 4th and Polish 1st Armoured Divisions managed to force a crossing of the Laison River. Limited access to the crossing points over the Dives River allowed counterattacks by the German 102nd SS Heavy Panzer Battalion.[6] The town of Potigny fell to Polish forces in the late afternoon.[12] By the end of the first day, elements of the Canadian 3rd and 4th Divisions had reached Point 159, directly north of Falaise, although they had been unable to break into the town. To bolster his offensive, Simonds ordered the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division to move toward the front, with the hope that this reinforcement would be sufficient to enable his divisions to capture the town.[13]

Although the first day's progress was slower than expected, Operation Tractable resumed on 15 August; both armoured divisions pushed southeast toward Falaise.[14] The Canadian 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions—with the support of the Canadian 2nd Armoured Brigade—continued their drive south towards the town.[15] After harsh fighting, the 4th Armoured Division captured Soulangy but the gains made were minimal as strong German resistance prevented a breakthrough to Trun.[16] On 16 August, the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division broke into Falaise, encountering minor opposition from Waffen-SS units and scattered pockets of German infantry.[13] Although it would take two more days to clear all resistance in the town, the first major objective of Operation Tractable had been achieved. Simonds began to reorganize the bulk of his armoured forces for a renewed push towards Trun to close the Falaise Pocket.[14]

16–19 August

Drives for Trun and Chambois

The drive for Trun by Polish and Canadian Armoured Divisions began on 16 August, with preliminary attacks in preparation for an assault against Trun and Chambois. On 17 August, both armoured divisions of the Canadian 1st Army advanced.[6] By early afternoon, the Polish 1st Armoured Division had outflanked the 12th SS Panzer Division, enabling several Polish formations to both reach the 4th Armoured Division's objectives and significantly expand the bridgehead northwest of Trun.[17] Stanisław Maczek—the Polish divisional commander—split his forces into three battlegroups each of an armoured regiment and an infantry battalion.[nb 1][18] One of these struck southwest, cutting off Trun and establishing itself on the high ground dominating the town and the Dives river valley, allowing for a powerful assault by the Canadian 4th Armoured Division on Trun. The town was liberated on the morning of 18 August.[19]

As Canadian and Polish forces liberated Trun, Maczek's second armoured battlegroup manoeuvred southeast, capturing Champeaux and anchoring future attacks against Chambois across a 6-mile (9.7 km) front.[17] At its closest, the front was 4 miles (6.4 km) from forces of the US V Corps in the town. By the evening of 18 August, all of Maczek's battlegroups had established themselves directly north of Chambois (one outside of the town, one near Vimoutiers and one[nb 2] at the foot of Hill 262).[21] With reinforcements quickly arriving from the 4th Canadian 4th Armoured Division, Maczek was in an ideal position to close the gap the following day. The presence of the Polish Armoured Division also alerted Generalfeldmarshall Walther Model of the need to keep the pocket open.[20]

Closing the Gap

Early on 19 August, LGen Simonds met with his divisional commanders to finalize plans for closing the gap. The 4th Armoured Division would attack toward Chambois, on the western flank of two battlegroups of the Polish 1st Armoured Division.[20] Two additional Polish battlegroups would strike eastward, securing Hill 262 to cover the eastern flanks of the assault.[16] The 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions would continue their grinding offensives against the northern extremities of the Falaise Pocket, inflicting heavy casualties on the exhausted remains of the 12th SS Panzer Division.[19] The assault began almost immediately after the meeting, with one battlegroup of the Polish 1st advancing toward Chambois and "Currie Task Force" of the 4th Armoured Division covering their advance. Simultaneously, two Polish battlegroups moved for Hill 262. Despite heavy German resistance, Battlegroup Zgorzelski was able to secure Point 137, directly west of Hill 262.[22] By early afternoon, Battlegroup Stefanowicz had captured the hill, annihilating a German infantry company in the process. As a result of the fighting, Polish casualties accounted for nearly 50% of those sustained by the Canadian 1st Army.[23]

By late afternoon of 19 August, Canadian and Polish forces had linked with the US 80th Division and 90th Division already stationed in the town. The Falaise Gap had been closed, trapping Model′s forces. As the linkup occurred, Model′s II SS Panzer Corps had begun its counterattack against Polish forces on Hill 262, hoping to reopen the pocket.[24] With American and Canadian forces facing German counterattacks in their sectors, the Polish forces would have to defend against two veteran Panzer divisions to keep the gap closed.

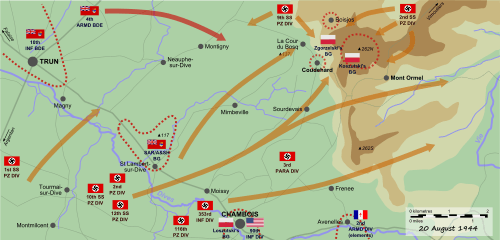

20 August

St. Lambert-sur-Dives and Hill 117

On the morning of 20 August, two German formations—the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions, attacked Polish positions on Hill 262.[24] At the same time, the 16th Infantry and 12th SS Panzer Divisions attacked American and Canadian forces from within the pocket, opening small channels through Allied positions. By mid-morning, 2,000 survivors of the German 2nd Parachute Division had managed to breach Canadian positions along the Dives River, as well as at Point 117.[25] At approximately noon, several units of the 10th SS, 12th SS and 116th Panzer Divisions managed to break through these weakened positions.[26]

By mid afternoon, reinforcements from an armoured battlegroup under Major David Vivian Currie managed to reach St. Lambert-sur-Dives, denying two German armies evacuation of the pocket. Over the next 36 hours, the battlegroup repulsed almost continual attacks by German forces, destroying seven German tanks, twelve 88 mm (3.46 in) anti-tank guns and 40 vehicles. In the brutal fighting around Lambert-sur-Dives, Currie's battlegroup was able to inflict nearly 2,000 casualties on attacking German forces, including 300 killed and 1,100 captured.[27] By the evening of 20 August, the Germans had exhausted their attack against St. Lambert-sur-Dives; the surviving members of the 84th Corps—commanded by General Elfeld—surrendered to Canadian and American forces near Chambois.[15] For his actions at St. Lambert-sur-Dives, Currie was awarded the Victoria Cross, the only Canadian so honoured for service in the Normandy Campaign.[27]

Hill 262 (Mont Ormel)

While Currie's force stalled German forces outside of St. Lambert, two battlegroups of Maczek's Polish 1st Armoured Division were engaged in a protracted battle with two well-trained SS Panzer divisions. Throughout the night of the 19th, Polish forces had entrenched themselves along the south, southwest and northeastern lines of approach to Hill 262.[28] Directly southwest of Mont Ormel, German units moved along what would later become known as "The Corridor of Death", as the Polish inflicted heavy casualties on German forces moving towards Mont Ormel with a well-coordinated artillery barrage.[26] The Polish infantry and armour were supported by the guns of the 58th Battery, 4th Medium Regiment, 2nd Canadian Army Group Royal Artillery (AGRA) and assisted by the Artillery observer, Pierre Sévigny. Captain Pierre Sévigny's assistance was crucial in defending Hill 262 and he later received the Virtuti Militari (Poland's highest military decoration) for his exertions during the battle.

From the northeast, the 2nd SS Panzer Division planned an assault in force against the four infantry battalions and two armoured regiments of the Polish 1st Armoured Division dug in on Hill 262.[26] The 9th SS Panzer Division would attack from the north, while simultaneously preventing Canadian units from reinforcing the Polish armoured division. Having managed to break out of the Falaise Pocket, the 10th SS, 12th SS and 116th Panzer Divisions would then attack Hill 262 from the southwest. If this major obstacle could be cleared, German units could initiate a full withdrawal from the Falaise Pocket.[29]

The first attack against Polish positions was by the "Der Führer" Regiment of the 2nd SS Panzer Division. Although the Podhale Rifles battalion was able to repel the attack, it expended a substantial amount of its ammunition in doing so.[30] The second attack was devastating to the dwindling armoured forces of the Polish battlegroups. A single German tank, positioned on Point 239 (northeast of Mont Ormel), was able to destroy five Sherman medium tanks within two minutes.[25] At this time, the 3rd Parachute Division—along with an armoured regiment of the 1st SS Panzer Division—attacked Mont Ormel from inside the Falaise Pocket. This attack was repulsed by the artillery, which "massacred" German infantry and armour closing in on their positions.[31]

As the assault from the southwest ran out of steam, the 2nd SS Panzer Division resumed its attack on the northeast of the ridge. Since Polish units were now concentrated on the southern edges of the position, the 2nd SS was able to force a path through to the 3rd Parachute Division by noon, opening a corridor out of the pocket.[31] By mid-afternoon, close to 10,000 German troops had escaped through the corridor.[31] Despite being overwhelmed by strong counterattacks, Polish forces continued to hold the high ground on Mont Ormel, which they referred to as "The Mace" (Maczuga), exacting a deadly toll on passing German forces through the use of well-coordinated artillery fire.[32] Irritated by the presence of these units, which were exacting a heavy toll on his men, Generaloberst Paul Hausser—commanding the 7th Army—ordered the positions to be "eliminated".[31] Although substantial forces, including the 352nd Infantry Division and several battlegroups from the 2nd SS Panzer Division inflicted heavy casualties on the 8th and 9th Battalions of the Polish 1st Armoured Division, the counterattack was ultimately fought off. The battle had cost the Poles almost all of their ammunition, leaving them in a precarious position.[32]

At 19:00 on 20 August, a 20-minute ceasefire was arranged to allow German forces to evacuate a large convoy of medical vehicles. Immediately following the passage of these vehicles, the fighting resumed and intensified. Although the Germans were incapable of dislodging the Polish forces, the hill's defenders had reached the point of exhaustion.[25] With ammunition supplies extremely low, the Poles were forced to watch as the remnants of the XLVII Panzer Corps escaped from the pocket. Despite this, Polish artillery continued to bombard every German unit that entered the evacuation corridor. Stefanowicz—commander of the Polish battlegroups on Hill 262—was sceptical of his force's chance of survival:[33]

Gentlemen. Everything is lost. I do not believe [the] Canadians will manage to help us. We have only 110 men left, with 50 rounds per gun and 5 rounds per tank ... Fight to the end! To surrender to the SS is senseless, you know it well. Gentlemen! Good luck – tonight, we will die for Poland and civilization. We will fight to the last platoon, to the last tank, then to the last man.[33]

21 August

After the brutality of the combat that had occurred during the day, night was welcomed by both German and Polish forces surrounding Mont Ormel. Fighting was sporadic, as both sides avoided contact with one another. Frequent Polish artillery barrages interrupted German attempts to retreat from the sector.[32] By morning, German attacks on the position had resumed. Although not as coordinated as on the day before,[34] the attack still managed to reach the last of the Polish defenders on Mont Ormel. As the remaining Polish forces repelled the assault, their tanks were forced to use the last of their ammunition.[34] At approximately 12:00, the last SS remnants launched a final assault on the positions of the 9th Battalion. Polish forces defeated them at point-blank range. There would be no further attacks; the two battlegroups of the Polish 1st Armoured Division had survived the onslaught, despite being surrounded by German forces for three days. Both Reynolds and McGilvray place the Polish losses on the Maczuga at 351 killed and wounded and 11 tanks lost,[35][36] although Jarymowycz gives higher figures of 325 killed, 1,002 wounded, and 114 missing — approximately 20% of the division's combat strength.[26] Within an hour, The Canadian Grenadier Guards managed to link up with what remained of Stefanowicz's men.[16] By late afternoon, the remainder of the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions had begun their retreat to the Seine River.[37] The Falaise Gap had been permanently closed, with a large number of German forces still trapped in the pocket.[38]

Aftermath

By the evening of 21 August 1944, the vast majority of the German forces remaining in the Falaise Pocket had surrendered.[15] Nearly all of the strong German formations that had caused significant damage to the Canadian 1st Army throughout the Normandy campaign had been destroyed. Two panzer divisions—the Panzer Lehr and 9th SS—now existed in name only.[39] The formidable 12th SS Panzer Division had lost 94% of its armour, nearly all of its field-guns and 70% of its vehicles. Several German units, notably the 2nd and the 12th SS Panzer Divisions had managed to escape east toward the Seine River, albeit without most of their motorized equipment. Conservative estimates for the number of German soldiers captured in the Falaise Pocket approach 50,000,[40] although some estimates put total German losses (killed and captured) in the Pocket as high as 200,000.[37]

By 23 August, the remainder of the Wehrmacht's Seventh Army had entrenched itself along the Seine River,[39] in preparation for the defence of Paris. Simultaneously, elements of Army Group G—including the German 15th Army and the 5th Panzer Army—moved to engage American forces in the south. In the following week, elements of the Canadian 1st Army repeatedly attacked these German units on the Seine in attempts to break through to the Channel Ports.[41] On the evening of 23 August, French and American Army units entered Paris.[42]

Casualties

Due to the successive offensives of early August, exact Canadian casualties for Operation Tractable are not known but losses during Totalize and Tractable are put at 5,500 men.[43] German casualties during Operation Tractable are also uncertain; approximate figures can be found for casualties within the Falaise Pocket but not for the Canadian operations during Tractable. After the Falaise Pocket, the German 7th Army was severely depleted, having lost from 50,000–200,000 men, over 200 tanks, 1,000 guns and 5,000 other vehicles.[39] In the fighting around Hill 262, the Germans lost 2,000 men killed, 5,000 taken prisoner, 55 tanks, 44 guns and 152 armoured vehicles.[35] Polish casualties for Operation Tractable (until 22 August) are 1,441 men, of whom 325 were killed (including 21 officers), 1,002 were wounded (35 officers) and 114 missing, which includes 263 men lost before the Chambois and Ormel actions from 14–18 August.[35][24]

Battle honours

In the British and Commonwealth system of battle honours, participation in Operation Tractable (included as part of the honour Falaise for service from 7–22 August) was recognized in 1957, 1958, and 1959 by the award of the battle honours Laison (or "The Laison" for Canadian units), for service on 14–17 August, Chambois from 18–22 August and St Lambert-sur-Dives from 19–22 August.[44]

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

- 1 2 Fortin, p. 68

- 1 2 Van der Vat, p. 163

- ↑ D'Este, p. 404

- ↑ Zuehlke, p. 168

- 1 2 Bercuson, p. 230

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bercuson, p. 231

- ↑ McGilvray, p. 52

- ↑ D'Este, p. 429

- ↑ Bercuson, p. 229

- ↑ D'Este, p. 430

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 419

- ↑ "Operation Tractable". Memorial Mont-Ormel. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- 1 2 Copp. p. 104

- 1 2 Jarymowycz, p. 188

- 1 2 3 Van der Vat, p. 169

- 1 2 3 Bercuson, p. 232

- 1 2 3 Jarymowycz, p. 192

- ↑ Stacey, p. 260

- 1 2 Zuehlke, p. 169

- 1 2 3 Jarymowycz, p. 193

- ↑ Stacey, p. 261

- ↑ "Closing the Falaise Gap". Memorial Mont-Ormel. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ↑ Jarymowycz, p. 195. By the night of August 18, Polish fatalities totaled 263, while Canadian fatalities totaled 284

- 1 2 3 Jarymowycz, p. 195

- 1 2 3 "2nd SS Panzer Corps counterattack". Memorial Mont-Ormel. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Jarymowycz, p. 196

- 1 2 "David Vivian Currie's Victoria Cross". Veteran Affairs Canada. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ↑ D'Este, p. 456

- ↑ Fey, p. 175

- ↑ Jarymowycz, p. 197

- 1 2 3 4 Van der Vat, p. 168

- 1 2 3 D'Este, p. 458

- 1 2 Jarymowycz, p. 201

- 1 2 "The End of the German 7th Army". Memorial Mont-Ormel. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- 1 2 3 McGilvray, p. 54

- ↑ Reynolds, p. 280

- 1 2 Bercuson, p. 233

- ↑ Fey, p. 176

- 1 2 3 Keegan, p. 410

- ↑ D'Este, p. 455

- ↑ Copp, p. 106

- ↑ Keegan, p. 414

- ↑ Jarymowycz, p. 203

- ↑ Rodger, p. 248

References

- Books

- Bercuson, David (1995) Maple leaf Against the Axis. Ottawa: Red Deer Press. ISBN 0-88995-305-8

- Bercuson, David (2004). M Waffen-SS. Stackpole Books. Mechanicsburg PA.ISBN 978-0-8117-2905-5

- D'Este, Carlo (1983). Decision in Normandy. New York: Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 1-56852-260-6

- Fey, William [1990] (2003). Armor battles of the Waffen-SS, 1943–45. Stackpole Books. Mechanicsburg PA. ISBN 0-81172-905-2.

- Fortin, Ludovic (2004). British Tanks In Normandy. Paris: Histoire & Collections. ISBN 2-915239-33-9.

- Jarymowycz, Roman (2001). Tank Tactics; from Normandy to Lorraine. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-55587-950-0

- Keegan, John (1989). The Second World War. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-3035-73-8.

- McGilvray, Evan (2004). The Black Devils March, a Doomed Odyssey: The 1st Polish Armoured Division 1939–1945. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-874622-42-0.

- Napier, S. (2015). Armoured Campaign in Normandy June–August 1944. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-75096-270-4.

- Reynolds, Michael (2001) [1997]. Steel Inferno: I SS Panzer Corps in Normandy. Da Capo Press. ISBN 1-885119-44-5.

- Rodger, Alexander (2003). Battle Honours of the British Empire and Commonwealth Land Forces. Marlborough: Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-637-5.

- Stacey, Colonel C. P.; Bond, Major C. C. J. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. III. Ottawa: The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 829337883. Retrieved 2013-05-19.

- Van der Vat, D. (2003). D-Day; The Greatest Invasion, A People's History. Toronto: Madison Press. ISBN 1-55192-586-9.

- Wilmot, C. (1997). The Struggle for Europe. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-85326-677-9.

- Zuehlke, M. (2001). The Canadian Military Atlas. London: Stoddart. ISBN 0-7737-3289-6.

- Journals

- Maczek, Stanisław (2006) [1944]. "The First Polish Armoured Division in Normandy". Canadian Military History. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. 15 (2): 51–70. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

External links

- Analysis of Operation Cobra and the Falaise Gap Manoeuvres in WWII, Granier, T. R. (1985)

- AAF Counter-Air Operations April 1943 – June 1944

- Situation Maps Western Europe Day-by-Day

Coordinates: 48°53′34″N 0°11′31″W / 48.89278°N 0.19194°W