Operation Titanic

| Operation Titanic | |

|---|---|

| Part of Operation Bodyguard | |

The D-Day naval deceptions made up one part of Operation Bodyguard. | |

| Operational scope | Tactical Deception |

| Location | English Channel |

| Planned | 1944 |

| Planned by | London Controlling Section, Ops (B), Allied Expeditionary Air Force |

| Objective | |

| Date | 5–6 June 1944 |

| Executed by | No. 138 Squadron RAF No. 161 Squadron RAF No. 90 Squadron RAF No. 149 Squadron RAF Special Air Service |

| Outcome | Allied success |

| Casualties | 2 Short Stirling of No. 149 Squadron and their crews 8 Men Special Air Service killed or executed |

Operation Titanic was a series of military deceptions carried out by the Allied Nations during the Second World War. The operation formed part of Operation Bodyguard, the cover plan for the Normandy landings in 1944. Titanic was carried out on 5–6 June 1944 by the Royal Air Force and the Special Air Service. The objective of the operation was to drop 500 dummy parachutists in places other than the real Normandy drop zones, to deceive the German defenders into believing that a large force had landed, drawing their troops away from the beachheads.

Titanic was one of several deception operations involving the Royal Air Force on D-Day; others were Operations Glimmer and Taxable, executed by No. 218 Squadron and No. 617 Squadron, and radar deceptions by No. 101 and No. 214 squadrons.

Background

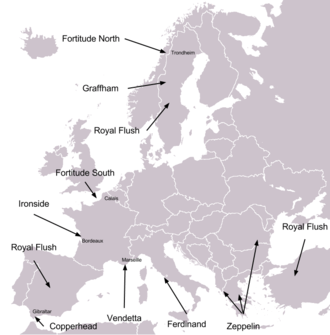

Operation Titanic formed part of Operation Bodyguard, a broad strategic military deception intended to confuse the Axis high command as to Allied intentions during the lead-up to the Normandy landings.[1] The most complex portion of Bodyguard involved a wide ranging strategic deception, organised by the London Controlling Section (LCS), in southern England called Fortitude South.[2] Through decoy hardware, radio transmissions and double agents, Fortitude attempted to inflate the size of the Allied force in England and develop a threat against the Pas-de-Calais (rather than Normandy, the real target of Operation Overlord).[3]

As D-Day approached, Allied planners moved on to tactical deceptions (roughly under the umbrella of Fortitude) to help cover the progress of the real invasion forces. The D-Day naval deceptions (Taxable and Glimmer) were planned for the eve of the Normandy landings to develop threats against the Pas-de-Calais involving No. 218 Squadron and No. 617 Squadron of the Royal Air Force and Harbour Defence Motor Launch's of the home fleet.[4] Titanic was intended as an accompaniment to these deceptions, as well as to create general confusion for the defending forces on the morning of D-Day. It simulated paratrooper drops (using dummies and small numbers of SAS personnel). The idea for Titanic originated from a plan submitted by David Strangeways (head of the tactical deception unit of 21st Army Group) which in turn was a rewrite of a plan from the Supreme HQ Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) Ops (B).[5]

Operation

Titanic was divided into four operations (I to IV), consisting of various combinations of dummy paratroopers, noisemakers, chaff (codenamed Window) and SAS personnel. The noisemakers, codenamed Pintails, were attached to each dummy to simulate rifle fire. They also carrier a small explosive timed to destroy the dummy and give the appearance of a paratrooper burning his parachute.[2][5] Four squadrons from No. 3 Group RAF (the special duties squadrons) carried out the drops. No. 138 and No. 161, flying Handley Page Halifaxs and Lockheed Hudsons, as well as No. 90 and No. 149, flying Short Stirlings.

M. R. D. Foot, intelligence officer for the SAS brigade, was ordered to arrange the special forces contingent. He first approached the head of 1st SAS Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Paddy Mayne, who refused to take part in an intelligence operation, having had a bad experience implementing deception plans whilst in north Africa. However, Lieutenant Colonel Brian Franks of the 2nd SAS Regiment was convinced to take part in the operation.[6] 2nd SAS provided twelve men under the command of Captain Frederick James Fowles(Chick) and Lieutenant Norman Harry Poole. After landing these teams were to locate and open fire on the German forces, allowing some to escape in the hope they would report the parachute drops.[7]

In total, around four hundred dummies were planned to be dropped as part of the operation. Titanic I simulated the drop of an airborne division north of the Seine river; near Yvetot, Yerville, Doudeville in the Seine-Maritime region and Fauville in the Eure region. Two hundred dummies and two SAS teams were parachuted in across these four Titanic I targets. Titanic II would have involved dropping fifty dummies east of the Dives River to draw German reserves onto that side of the river. However, this segment of the operation was cancelled just before 6 June. A further fifty dummies were dropped, under Titanic III, in the Calvados region near Maltot and the woods to the north of Baron-sur-Odon to draw German reserves away to the west of Caen. Finally, Titanic IV involved two hundred dummies dropped near Marigny in the Manche, as with Titanic I the intention was to simulate the dropping of an airborne division.[7] Two SAS teams were also dropped near Saint-Lô. This group commanded by Captain Fowles and Lieutenant Poole landed at 00:20 on 6 June 1944, 10 minutes ahead of schedule.[8] To deceive the Germans into thinking there was a large parachute landing in progress, the SAS teams played 30 minute pre-recorded sounds of men shouting and weapons fire including mortars.[7]

The mission went according to plan. The only aircraft lost were two Short Stirlings and their crews from No. 149 Squadron taking part in Titanic III. Eight men from the SAS failed to return; they were all either killed in action or executed by the Germans in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.[7][9][10]

Impact

At 02:00 on 6 June 1944, the Germans reported the landing of parachutists east of Caen and in the Coutances, Valognes and Saint-Lô areas and hearing ships engines out at sea. In response the Germans ordered the 7th Army to increase the level of their preparedness and to expect an invasion, but General Hans Speidel decreased the level of alert when it was reported only dummy parachutists had been found.[11] However, Generalfeldmarshall Gerd von Rundstedt ordered the 12th SS Panzerdivision Hitlerjugend to deal with a supposed parachute landing on the coast near Lisieux which was found to consist solely of dummies from Titanic III.[11] The dummies and SAS teams of Titanic IV diverted a Kampfgruppe from the 915th Grenadier Regiment, the 352nd Infantry Division reserve away from the Omaha and Gold beaches and the 101st Airborne Divisions drop zones.[8] The regiment, believing an airborne division had landed, were employed searching woods instead of heading to the invasion beaches.[11] Enigma intercepts from the area of Titanic I revealed that the German commander was reporting a major landing up the coast from Le Havre (well to the north of the landing beaches) and that he had been cut off by them.[11]

References

Bibliography

- Barbier, Mary (2007). D-day deception: Operation Fortitude and the Normandy invasion. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-2759-9479-2.

- Foot, M R D (12 May 1994). "Why we remember that June day". London: The Independent.

- Godson, Roy; Wirtz, James J (2003). Strategic denial and deception: the twenty-first century challenge. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0898-6.

- Holt, Thaddeus (2004). The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-5042-7.

- Latimer, Jon (2001). Deception in War. New York: New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-381-0.

- Levine, Joshua (2011). Operation Fortitude : the true story of the key spy operation of WWII that saved D-Day. London: Collins. ISBN 9780007313532.

- Ramsey, Winston G (1995). D-Day then and now, Volume 1. Battle of Britain Prints International. ISBN 0-900913-84-3.

External links

- "Operation Titanic (D-Day)-Oscar was no dummy, or was he?". Retrieved January 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "D-Day Revisited — RAF Operations". Retrieved January 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "D Day Timeline". Royal Air Force. Retrieved 25 July 2010.