Maury County, Tennessee

| Maury County, Tennessee | ||

|---|---|---|

Maury County Courthouse in Columbia | ||

| ||

|

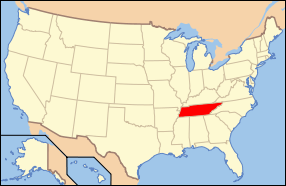

Location in the U.S. state of Tennessee | ||

Tennessee's location in the U.S. | ||

| Founded | 1807 | |

| Named for | Abram Poindexter Maury[1] | |

| Seat | Columbia | |

| Largest city | Columbia | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 616 sq mi (1,595 km2) | |

| • Land | 613 sq mi (1,588 km2) | |

| • Water | 2.4 sq mi (6 km2), 0.4% | |

| Population | ||

| • Total | 95,300 (2,014 est.) | |

| • Density | 132/sq mi (51/km²) | |

| Congressional districts | 4th, 7th | |

| Time zone | Central: UTC-6/-5 | |

| Website |

www | |

Maury County /ˈmɒreɪ/ or "murray" is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee, in the area legally known as Middle Tennessee. As of the 2010 census, the population was 80,956.[2] Its county seat is Columbia.[3]

Maury County is included in the Nashville-Davidson-Murfreesboro-Franklin, TN Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The county was formed in 1807 from Williamson County and Indian lands. Maury County was named in honor of Major Abram Poindexter Maury of Williamson County, who was a member of the Tennessee legislature, and an uncle of Commodore Matthew Fontaine Maury.[1]

The rich soil of Maury County led to a thriving agricultural sector, starting in the 19th century. The county was part of a 41-county region that became known and legally defined as Middle Tennessee. The area contains the majority of population in the state. Planters in Maury County relied on the labor of African-American slaves to raise and process cotton, tobacco and livestock (especially dairy cattle).

With the mechanization of agriculture, particularly from the 1930s, the need for farm labor in the county was reduced. In addition, many African Americans moved to northern and midwestern industrial cities in the 20th century for opportunities, particularly during the Great Migration. This movement out of the county continued after World War II. Other changes have led to increased population in the county since the late 20th century, and the county has led the state in beef cattle production.[1]

Columbia Race Riot of 1946

On the night of February 26–27, 1946, a disturbance known as the "Columbia Race Riot" took place in Columbia, the county seat. It was the first time in the state in which blacks had fought back to defend themselves from a white attack, and the national press defined it as the first "major racial confrontation" after World War II.[4] It marked a new spirit of resistance by veterans and others following African-American participation in World War II, which they believed should have earned them their full rights as citizens in the United States, even in the Jim Crow South.[5] James Stephenson, an African-American Navy veteran, was in a store with his mother who complained about being overcharged for poor repairs. A white repair apprentice, Billy Fleming hit Ms Stephenson; James Stephenson was a welterweight on the Navy boxing team and responded by sending Fleming through a glass window. Both Stephenson and his mother were arrested; Fleming's father convinced the sheriff to charge them with attempted murder. Hearing that Fleming had gone to the hospital, a white mob gathered and rumors were that the Stephensons would be lynched.[6]

Julius Blair, a 76-year-old store owner in the black community, arranged to have the Stephensons released to his custody, and he got them out of town for their protection. The white mob did not disperse, but a hundred black men patrolled their neighborhood, determined to resist. Four police officers were ambushed while walking in "Mink Slide", their name for the African-American business district, also known as "The Bottom". After this skirmish with police, state troopers arrived as reinforcements, soon outnumbering the blacks. The troopers participated in the subsequent attacks, ransacking businesses and rounding up people. They cut off phone service to Mink Slide, but the owner of a funeral home got a call through to Nashville and asked for help from the NAACP. The county jail was overcrowded with black suspects, who were questioned for days without counsel. In the disturbance, two black men were killed "trying to escape."[7] More than 20 black men were eventually charged with rioting and attempted murder.

The NAACP sent Thurgood Marshall as the lead attorney to defend Stephenson and other blacks in the case, with trials taking place during the summer of 1946. He was assisted by two local attorneys, Zephaniah Alexander Looby, originally from the British West Indies but later to serve as a member of the Nashville City Council, and Maurice Weaver, a local white activist lawyer. Marshall was also preparing litigation for education and voting rights cases; in 1954 he gained a ruling by the United States Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Marshall later was appointed as the first black United States Supreme Court justice.[8] In Columbia, Marshall achieved acquittals of 23 black men from an all-white jury.[4] At the last trials in November 1946, he also won acquittal for Rooster Bill Pillow, and a reduction in sentence for Papa Kennedy, which allowed him free on bail.[9]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 616 square miles (1,600 km2), of which 613 square miles (1,590 km2) is land and 2.4 square miles (6.2 km2) (0.4%) is water.[10]

Adjacent counties

- Williamson County (north)

- Marshall County (east)

- Giles County (south)

- Lawrence County (southwest)

- Lewis County (west)

- Hickman County (northwest)

National protected area

- Natchez Trace Parkway (part)

State protected areas

- Duck River Complex State Natural Area

- James K. Polk Home (state historic site)

- Stillhouse Hollow Falls State Natural Area

- Williamsport Wildlife Management Area

- Yanahli Wildlife Management Area

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 10,359 | — | |

| 1820 | 22,141 | 113.7% | |

| 1830 | 27,665 | 24.9% | |

| 1840 | 28,186 | 1.9% | |

| 1850 | 29,520 | 4.7% | |

| 1860 | 32,498 | 10.1% | |

| 1870 | 36,289 | 11.7% | |

| 1880 | 39,904 | 10.0% | |

| 1890 | 38,112 | −4.5% | |

| 1900 | 42,703 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 40,456 | −5.3% | |

| 1920 | 35,403 | −12.5% | |

| 1930 | 34,016 | −3.9% | |

| 1940 | 40,357 | 18.6% | |

| 1950 | 40,368 | 0.0% | |

| 1960 | 41,699 | 3.3% | |

| 1970 | 43,376 | 4.0% | |

| 1980 | 51,095 | 17.8% | |

| 1990 | 54,812 | 7.3% | |

| 2000 | 69,498 | 26.8% | |

| 2010 | 80,956 | 16.5% | |

| Est. 2015 | 87,757 | [11] | 8.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] 1790-1960[13] 1900-1990[14] 1990-2000[15] 2010-2014[2] | |||

As of the census[17] of 2000, there were 69,498 people, 26,444 households, and 19,277 families residing in the county. The population density was 113 people per square mile (44/km²). There were 28,674 housing units at an average density of 47 per square mile (18/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 57% White, 41% Black or African American, 0.31% Native American, 0.33% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 1.44% from other races, and 1.25% from two or more races. 3.26% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 26,444 households out of which 34.80% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.90% were married couples living together, 12.90% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.10% were non-families. 23.20% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.80% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.58 and the average family size was 3.03.

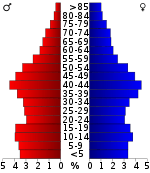

In the county, the population was spread out with 26.20% under the age of 18, 8.70% from 18 to 24, 29.80% from 25 to 44, 23.20% from 45 to 64, and 12.00% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 94.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.30 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $41,591, and the median income for a family was $48,010. Males had a median income of $37,675 versus $23,334 for females. The per capita income for the county was $19,365. About 8.30% of families and 10.90% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.50% of those under age 18 and 12.10% of those age 65 or over.

There were declines in population and declines in population growth from 1900 to 1930, and from 1940 to 1970. These periods related to the migration of people from rural to urban areas for work, especially as mechanization reduced the need for agricultural laborers. In addition, these time periods related to the Great Migration of African Americans out of the Jim Crow South to northern and midwestern industrial cities for more opportunities. The African-American population became highly urbanized. Expansion of the railroads, auto and steel industries provided new work opportunities in the early 20th century.

Transportation

The Maury County Airport is a county-owned public-use airport located 2 nautical miles (3.7 km; 2.3 mi) northeast of the central business district of Mount Pleasant[18] and 8 nautical miles (15 km; 9.2 mi) southwest of Columbia.[19]

Communities

Cities

- Columbia (county seat)

- Mount Pleasant

- Spring Hill (partly in Williamson County)

Census-designated place

- Summertown (mostly in Lawrence County and a small portion in Lewis County)

Unincorporated communities

- Ashwood

- Carters Creek

- Culleoka

- Glendale

- Fly

- Fountain Heights

- Hampshire

- Hopewell

- Mt. Joy

- Neapolis

- Santa Fe

- Sawdust

- Williamsport

Notable people

- James Philip Eagle – the 16th Governor of the State of Arkansas[20]

- Cordie Cheek, 19-year-old lynched in 1933 by a mob including county officials when he was falsely accused of rape[21]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Marise P. Lightfoot, "Maury County," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 11 March 2013.

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- 1 2 King (2012), Devil in the Grove, p. 8

- ↑ Gilbert King, Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America, HarperCollins, 2012, pp. 7-20

- ↑ King (2012), Devil in the Grove, p. 11

- ↑ King (2012), Devil in the Grove, p. 13

- ↑ Carroll Van West. "Columbia race riot, 1946". Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ King (2012), Devil in the Grove, p. 14

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ "County Totals Dataset: Population, Population Change and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ Based on 2000 census data

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ FAA Airport Master Record for MRC (Form 5010 PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. Effective August 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Distance and heading from Columbia, TN (35°36'54"N 87°02'40"W) to Maury County Airport (35°33'16"N 87°10'45"W)". Great Circle Mapper. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Arkansas Governor James Philip Eagle". National Governors Association. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ↑ King, Gilbert (2012). Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys and the Dawn of a New America. p. 12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maury County, Tennessee. |

- Official site

- Maury County, TNGenWeb - free genealogy resources for the county

- Maury County at DMOZ

- Columbia Daily Herald

|

Hickman County | Williamson County |  | |

| Lewis County | |

Marshall County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Lawrence County | Giles County |

Coordinates: 35°37′N 87°05′W / 35.62°N 87.08°W