Italian general election, 1992

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

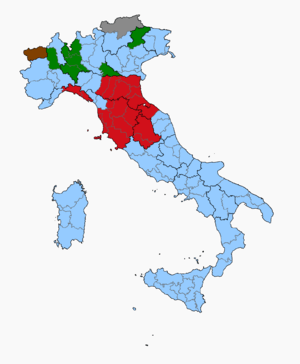

| Legislative election results map. Light Blue denotes provinces with a Christian Democratic plurality, Red denotes those with a Democratic Socialist plurality, Green denotes those with a Lega Nord plurality, Gray and Brown denotes those with a Regionalist plurality. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

General elections were held in Italy on April 5, 1992 for the 11th Parliament of the Republic.[3] They were the first without the traditionally second most important political force in Italian politics, the Italian Communist Party (PCI), which had been disbanded in 1991. It was replaced by a more social-democratic oriented force, the Democratic Party of the Left (PDS), and by a minority entity formed by members who did not want to renounce the communist tradition, the Communist Refoundation Party (PRC). However, put together they gained around 4% less than what the already declining PCI had obtained in the 1987 Italian general election, despite PRC had absorbed the disbanded Proletarian Democracy (DP).

The other major feature was the sudden rise of the federalist Lega Nord, which increased its vote from 0.5% of the preceding elections to more than 8%, increasing from a single member both in the Chamber and the Senate to 55 and 25, respectively. The onda lunga ("long wave") of Bettino Craxi's now centrist-oriented Italian Socialist Party, which in the past elections had been forecast next to overcome PCI, seemed to stop. Christian Democracy and the other traditional government parties, with the exception of the Republicans and the Liberals, also experienced a slight decrease in their vote.

Electoral system

The pure party-list proportional representation had traditionally become the electoral system for the Chamber of Deputies. Italian provinces were united in 32 constituencies, each electing a group of candidates. At constituency level, seats were divided between open lists using the largest remainder method with Imperiali quota. The remaining votes and seats were transferred at national level, where they were divided using the Hare quota, and automatically distributed to best losers into the local lists.

For the Senate, 237 single-seat constituencies were established, even if the assembly had risen to 315 members. The candidates needed a landslide victory of two thirds of votes to be elected, a goal which could be reached only by the German minorities in South Tirol. All remained votes and seats were grouped in party lists and regional constituencies, where a D'Hondt method was used: inside the lists, candidates with the best percentages were elected.

Historical background

In 1991 the Italian Communist Party split into the Democratic Party of the Left (PDS), led by Achille Occhetto, and the Communist Refoundation Party (PRC), headed by Armando Cossutta. Occhetto, leader of the PCI since 1988, stunned the party faithfully assembled in a working-class section of Bologna with a speech heralding the end of communism, a move now referred to in Italian politics as the svolta della Bolognina (Bolognina turning point). The collapse of the communist governments in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe had convinced Occhetto that the era of Eurocommunism was over, and he transformed the PCI into a progressive left-wing party, the PDS. Cossutta and a third of the PCI membership refused to join the PDS, and instead founded the Communist Refoundation Party.[4]

On 17 February 1992, judge Antonio Di Pietro had Mario Chiesa, a member of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), arrested for accepting a bribe from a Milan cleaning firm. The Italian Socialist Party distanced themselves from Chiesa. Bettino Craxi called Mario Chiesa mariuolo, or "villain", a "wild splinter" of the otherwise clean PSI. Upset over this treatment by his former colleagues, Chiesa began to give information about corruption implicating his colleagues. This marked the beginning of the Mani pulite investigation; news of political corruption began spreading in the press.

In February 1991, Lega Nord, which was first launched as an upgrade of Alleanza Nord in December 1989, was officially transformed into a party through the merger of various regional parties, notably including Lega Lombarda and Liga Veneta, under the leadership of Umberto Bossi. These continue to exist as "national sections" of the federal party, which presents itself in regional and local contests as "Lega Lombarda–Lega Nord", "Liga Veneta–Lega Nord", "Lega Nord–Piemont", and so on.[5][6][7]

The League exploited resentment against Rome's centralism (with the famous slogan Roma ladrona, which loosely means "Rome big thief") and the Italian government, common in northern Italy as many northerners felt that the government wasted resources collected mostly from northerners' taxes.[8] Cultural influences from bordering countries in the North and resentment against illegal immigrants were also exploited. The party's electoral successes began roughly at a time when public disillusionment with the established political parties was at its height. The Tangentopoli corruption scandals, which invested most of the established parties, were unveiled from 1992 on.[6][7] However, contrarily to what many pundits observed at the beginning of the 1990s, Lega Nord became a stable political force and it is by far the oldest party among those represented in the Italian Parliament.

Lega Nord's first electoral breakthrough was at the 1990 regional elections, but it was with the 1992 general election that the party emerged as a leading political actor. Having gained 8.7% of the vote, 56 deputies and 26 senators,[9] it became the fourth largest party of the country and within Parliament.

Parties and leaders

Results

the Christian Democracy (DC) party lost many votes, but its coalition prior to the elections managed to keep a small majority, while opposition parties gained votes. However the largest opposition party Italian Communist Party split after the fall of the Soviet Union and there was no opposition leadership. Many votes went to Lega Nord, a party that was not inclined to alliances at the time. The resulting parliament was therefore weak and difficult to bring to an agreement, and new elections arrived as soon as 1994.

Fundamental to this exponential expansion was the general attitude of the main politicians to drop support for minor politicians who got caught; this made many of them feel betrayed, and they often implicated many other politicians, who in turn would implicate even more. On 2 September 1992, the Socialist politician Sergio Moroni, charged with corruption, committed suicide. He left a letter pleading guilty, declaring that crimes were not for his personal gain but for the party's benefit, and accused the financing system of all parties.

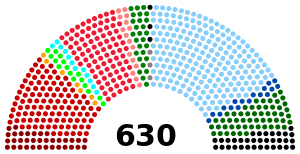

Chamber of Deputies

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democracy | 11,640,265 | 29.66 | 206 | −28 | |

| Democratic Party of the Left | 6,321,084 | 16.11 | 107 | −70 | |

| Italian Socialist Party | 5,343,930 | 13.62 | 92 | −2 | |

| Lega Nord | 3,396,012 | 8.65 | 55 | +54 | |

| Communist Refoundation Party | 2,204,641 | 5.62 | 35 | New | |

| Italian Social Movement | 2,107,037 | 5.37 | 34 | −1 | |

| Italian Republican Party | 1,722,465 | 4.39 | 27 | +6 | |

| Italian Liberal Party | 1,121,264 | 2.86 | 17 | +6 | |

| Federation of the Greens | 1,093,995 | 2.79 | 16 | +3 | |

| Italian Democratic Socialist Party | 1,064,647 | 2.71 | 16 | −1 | |

| The Network | 730,171 | 1.86 | 12 | New | |

| Pannella List | 485,694 | 1.24 | 7 | −6 | |

| Yes Referendum | 485,694 | 0.81 | 0 | New | |

| Pensioners' Party | 485,694 | 0.81 | 0 | New | |

| Other Leagues | 220,559 | 0.56 | 0 | New | |

| South Tyrolean People's Party | 198,447 | 0.51 | 3 | ±0 | |

| Hunting, Fishing, Environment | 192,799 | 0.49 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Federalism–Pensioners Living Men (UV–PSd'Az–SSK–UfS–Others) | 154,621 | 0.39 | 1 | New | |

| Lega Autonomia Veneta | 152,301 | 0.39 | 1 | New | |

| Housewives–Pensioners League | 133,717 | 0.34 | 0 | New | |

| Autonomist Lists | 94,583 | 0.24 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Southern Action League | 53,759 | 0.14 | 0 | New | |

| Autonomous Veneto | 49,035 | 0.12 | 0 | New | |

| Federalist Greens | 42,647 | 0.11 | 0 | New | |

| Aosta Valley coalition | 41,404 | 0.11 | 1 | ±0 | |

| Others | 116,007 | 0.30 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 2,232,489 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 41,479,764 | 100 | 630 | ±0 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 47,486,964 | 87.35 | – | – | |

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||||

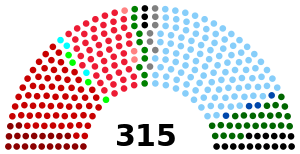

Senate of the Republic

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democracy | 9,088,494 | 27.27 | 107 | −18 | |

| Democratic Party of the Left | 5,682,888 | 17.05 | 64 | −37 | |

| Italian Socialist Party | 4,523,873 | 13.57 | 49 | +13 | |

| Lega Nord | 2,732,461 | 8.20 | 25 | +24 | |

| Communist Refoundation Party | 2,171,950 | 6.52 | 20 | New | |

| Italian Social Movement | 2,171,215 | 6.51 | 16 | ±0 | |

| Italian Republican Party | 1,565,142 | 4.70 | 10 | +2 | |

| Federation of the Greens | 1,027,303 | 3.08 | 4 | +3 | |

| Italian Liberal Party | 939,159 | 2.82 | 4 | +1 | |

| Italian Democratic Socialist Party | 853,895 | 2.56 | 3 | −2 | |

| Yes Referendum | 332,318 | 1.00 | 0 | New | |

| The Network | 239,868 | 0.72 | 3 | New | |

| Pensioners' Party | 215,889 | 0.65 | 0 | New | |

| Federalism–Pensioners Living Men (UV–PSd'Az–SSK–UfS–Others) | 174,713 | 0.52 | 1 | New | |

| South Tyrolean People's Party | 168,113 | 0.50 | 3 | +1 | |

| Pannella List | 166,708 | 0.50 | 0 | −3 | |

| For Calabria | 143,976 | 0.43 | 2 | New | |

| Lega Autonomia Veneta | 142,446 | 0.43 | 1 | New | |

| Housewives-Pensioners League | 134,327 | 0.40 | 0 | New | |

| Lega Alpina Lumbarda | 119,153 | 0.36 | 1 | New | |

| Hunting, Fishing, Environment | 116,395 | 0.35 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Autonomist Lists | 95,687 | 0.29 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Autonomous Veneto | 50,938 | 0.15 | 0 | New | |

| Southern Action League | 49,769 | 0.15 | 0 | New | |

| For Molise | 48,352 | 0.15 | 1 | New | |

| Federalist Greens | 47,051 | 0.14 | 0 | New | |

| Aosta Valley coalition | 34,150 | 0.10 | 1 | ±0 | |

| Others | 151,170 | 0.45 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 2,409,646 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 35,651,621 | 100 | 315 | ±0 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 41,022,758 | 86.9 | – | – | |

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||||

References

- ↑ Members of PDS parliamentary groups after the disbandment of the Communist Party.

- ↑ Due to impossibility of direct confrontation cause the disbandment of the Communist Party, the percentage refers to the empiric sum of PDS and PRC in 1992, and the result of PCI and DP in 1987.

- ↑ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1048 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- ↑ Kertzer, David I. (1998). Politics and Symbols: The Italian Communist Party and the Fall of Communism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07724-7.

- ↑ Ignazi, Pietro (2008). Partiti politici in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino. p. 88.

- 1 2 Ginsborg, Paul (1996). L'Italia del tempo presente. Turin: Einaudi. pp. 336–337, 534–535.

- 1 2 Galli, Giorgio (2001). I partiti politici italiani. Milan: BUR. pp. 379–380, 384.

- ↑ Rumiz, Paolo (2001). La secessione leggera. Dove nasce la rabbia del profondo Nord. Milan: Feltrinelli. pp. 10–13.

- ↑ Parenzo, David; Romano, Davide (2009). Romanzo padano. Da Bossi a Bossi. Storia della Lega. Milan: Sperling & Kupfer. pp. 263–266.