Herpesviral encephalitis

| Herpesviral encephalitis | |

|---|---|

| |

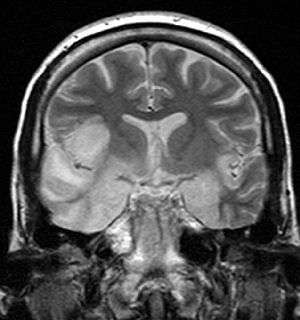

| coronal T2-weighted MR image shows high signal in the temporal lobes including hippocampal formations and parahippogampal gyrae, insulae, and right inferior frontal gyrus. A brain biopsy was performed and the histology was consistent with encephalitis. PCR was repeated on the biopsy specimen and was positive for HSV | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | B00.4 |

| ICD-9-CM | 054.3 |

| eMedicine | article/1165183 article/341142 |

Herpesviral encephalitis is encephalitis due to herpes simplex virus.

Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) is a viral infection of the human central nervous system. It is estimated to affect at least 1 in 500,000 individuals per year[1] and some studies suggest an incidence rate of 5.9 cases per 100,000 live births.[2] The majority of cases of herpes encephalitis are caused by herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), the same virus that causes cold sores. 57% of American adults are infected with HSV-1,[3] which is spread through droplets, casual contact, and sometimes sexual contact, though most infected people never have cold sores. About 10% of cases of herpes encephalitis are due to HSV-2, which is typically spread through sexual contact. About 1 in 3 cases of HSE result from primary HSV-1 infection, predominantly occurring in individuals under the age of 18; 2 in 3 cases occur in seropositive persons, few of whom have history of recurrent orofacial herpes. Approximately 50% of individuals that develop HSE are over 50 years of age.[4]

Pathophysiology

HSE is thought to be caused by the transmission of virus from a peripheral site on the face following HSV-1 reactivation, along a nerve axon, to the brain.[1] The virus lies dormant in the ganglion of the trigeminal cranial nerve, but the reason for reactivation, and its pathway to gain access to the brain, remains unclear, though changes in the immune system caused by stress clearly play a role in animal models of the disease. The olfactory nerve may also be involved in HSE,[5] which may explain its predilection for the temporal lobes of the brain, as the olfactory nerve sends branches there. In horses, a single-nucleotide polymorphism is sufficient to allow the virus to cause neurological disease;[6] but no similar mechanism has been found in humans.

Presentation

Most individuals with HSE show a decrease in their level of consciousness and an altered mental state presenting as confusion, and changes in personality. Increased numbers of white blood cells can be found in patient's cerebrospinal fluid, without the presence of pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Patients typically have a fever[1] and may have seizures. The electrical activity of the brain changes as the disease progresses, first showing abnormalities in one temporal lobe of the brain, which spread to the other temporal lobe 7–10 days later.[1] Imaging by CT or MRI shows characteristic changes in the temporal lobes (see Figure). Definite diagnosis requires testing of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) for presence of the virus. The testing takes several days to perform, and patients with suspected Herpes encephalitis should be treated with acyclovir immediately while waiting for test results.

Treatment

Herpesviral Encephalitis can be treated with high-dose intravenous aciclovir. Without treatment, HSE results in rapid death in approximately 70% of cases; survivors suffer severe neurological damage.[1] When treated, HSE is still fatal in one-third of cases, and causes serious long-term neurological damage in over half of survivors. Twenty percent of treated patients recover with minor damage. Only a small population of survivors (2.5%) regain completely normal brain function.[4] Earlier treatment (within 48 hours of symptom onset) improves the chances of a good recovery. Rarely, treated individuals can have relapse of infection weeks to months later. While the herpes virus can be spread, encephalitis itself is not infectious. Other viruses can cause similar symptoms of encephalitis, though usually milder (Herpesvirus 6, varicella zoster virus, Epstein-Barr, cytomegalovirus, coxsackievirus, etc.).

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whitley RJ (2006). "Herpes simplex encephalitis: adolescents and adults". Antiviral Res. 71 (2–3): 141–8. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.002. PMID 16675036.

- ↑ Kropp, Rhonda Y.; et al. (2006). "Neonatal herpes simplex virus infections in Canada: results of a 3-year national prospective study.". Pediatrics Vis. Sci. 117 (6): 1955–1962. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1778. PMID 16740836.

- ↑ Xu, Fujie; Sternburg Maya; Kottiri Benny; McQuilan Geraldine; Lee Francis; Nahmias Andre; Berman Stuart; Markowitz Larui (2006). "Trends in Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and Type 2 Seroprevalence in the United States". JAMA. 8. 296 (8): 964–73. doi:10.1001/jama.296.8.964. PMID 16926356.

- 1 2 Whitley RJ, Gnann JW (2002). "Viral encephalitis: familiar infections and emerging pathogens". Lancet. 359 (9305): 507–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07681-X. PMID 11853816.

- ↑ Dinn J (1980). "Transolfactory spread of virus in herpes simplex encephalitis". Br Med J. 281 (6252): 1392. doi:10.1136/bmj.281.6252.1392. PMC 1715042

. PMID 7437807.

. PMID 7437807. - ↑ van de Walle GR, Goupil R, Wishon C, et al. (2009). "A single‐nucleotide polymorphism in a herpesvirus DNA polymerase is sufficient to cause lethal neurological disease". J Infect Dis. 200 (1): 20–25. doi:10.1086/599316. PMID 19456260.

- Kumar M, Hill JM, Clement C, Varnell ED, Thompson HW, Kaufman HE (December 2009). "A double-blind placebo-controlled study to evaluate valacyclovir alone and with aspirin for asymptomatic HSV-1 DNA shedding in human tears and saliva". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50 (12): 5601–8. doi:10.1167/iovs.09-3729. PMC 2895993

. PMID 19608530.

. PMID 19608530. - Kaufman HE, Azcuy AM, Varnell ED, Sloop GD, Thompson HW, Hill JM (January 2005). "HSV-1 DNA in tears and saliva of normal adults". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46 (1): 241–7. doi:10.1167/iovs.04-0614. PMC 1200985

. PMID 15623779.

. PMID 15623779. - Hill JM, Zhao Y, Clement C, Neumann DM, Lukiw WJ (October 2009). "HSV-1 infection of human brain cells induces miRNA-146a and Alzheimer-type inflammatory signaling". NeuroReport. 20 (16): 1500–5. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283329c05. PMC 2872932

. PMID 19801956.

. PMID 19801956.

External links

- Encephalitis Global—A USA non-profit sharing an active discussion forum

- The Encephalitis Society—A Global resource on Encephalitis