Heat shock factor

| HSF-type DNA-binding | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | HSF_DNA-bind | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00447 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000232 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00381 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1hks | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1hks | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vertebrate heat shock transcription factor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Vert_HS_TF | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF06546 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR010542 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Heat shock factor (HSF), in molecular biology, is the name given to transcription factors that regulate the expression of the heat shock proteins.[1][2] A typical example is the heat shock factor of Drosophila melanogaster.[3]

Function

Heat shock factors (HSF) are transcriptional activators of heat shock genes.[3] These activators bind specifically to Heat Shock sequence Elements (HSE) throughout the genome[4] whose consensus-sequence is a tandem array of three oppositely oriented "AGAAN" motifs or a degenerate version thereof. Under non-stressed conditions, Drosophila HSF is a nuclear-localized unbound monomer, whereas heat shock activation results in trimerization and binding to the HSE.[5] The Heat Shock sequence Element is highly conserved from yeast to humans.[6]

Heat shock factor 1 (HSF-1) is the major regulator of heat shock protein transcription in eukaryotes. In the absence of cellular stress, HSF-1 is inhibited by association with heat shock proteins and is therefore not active. Cellular stresses, such as increased temperature, can cause proteins in the cell to misfold. Heat shock proteins bind to the misfolded proteins and dissociate from HSF-1. This allows HSF1 to form trimers and translocate to the cell nucleus and activate transcription.[7] Its function is not only critical to overcome the proteotoxic effects of thermal stress, but also needed for proper animal development and the overall survival of cancer cells.[8][9]

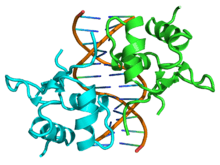

Structure

Each HSF monomer contains one C-terminal and three N-terminal leucine zipper repeats.[10] Point mutations in these regions result in disruption of cellular localisation, rendering the protein constitutively nuclear in humans.[5] Two sequences flanking the N-terminal zippers fit the consensus of a bi-partite nuclear localization signal (NLS). Interaction between the N- and C-terminal zippers may result in a structure that masks the NLS sequences: following activation of HSF, these may then be unmasked, resulting in relocalisation of the protein to the nucleus.[10] The DNA-binding component of HSF lies to the N-terminus of the first NLS region, and is referred to as the HSF domain.

Isoforms

Humans express the following heat shock factors:

| gene | protein |

|---|---|

| HSF1 | heat shock transcription factor 1 |

| HSF2 | heat shock transcription factor 2 |

| HSF2BP | heat shock transcription factor 2 binding protein |

| HSF4 | heat shock transcription factor 4 |

| HSF5 | heat shock transcription factor family member 5 |

| HSFX1 | heat shock transcription factor family, X linked 1 |

| HSFX2 | heat shock transcription factor family, X linked 2 |

| HSFY1 | heat shock transcription factor, Y-linked 1 |

| HSFY2 | heat shock transcription factor, Y-linked 2 |

References

- ↑ Sorger PK (May 1991). "Heat shock factor and the heat shock response". Cell. 65 (3): 363–6. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90452-5. PMID 2018972.

- ↑ Morimoto RI (March 1993). "Cells in stress: transcriptional activation of heat shock genes". Science. 259 (5100): 1409–10. doi:10.1126/science.8451637. PMID 8451637.

- 1 2 Clos J, Westwood JT, Becker PB, Wilson S, Lambert K, Wu C (November 1990). "Molecular cloning and expression of a hexameric Drosophila heat shock factor subject to negative regulation". Cell. 63 (5): 1085–97. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90511-C. PMID 2257625.

- ↑ Guertin, MJ; Lis, JT (Sep 2010). "Chromatin landscape dictates HSF binding to target DNA elements.". PLoS Genetics. 6 (9): e1001114. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001114. PMC 2936546

. PMID 20844575.

. PMID 20844575. - 1 2 Rabindran SK, Giorgi G, Clos J, Wu C (August 1991). "Molecular cloning and expression of a human heat shock factor, HSF1". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (16): 6906–10. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.16.6906. PMC 52202

. PMID 1871105.

. PMID 1871105. - ↑ Guertin, MJ; Petesch SJ; Zobeck KL; Min IM; Lis JT. (2010). "Drosophila heat shock system as a general model to investigate transcriptional regulation.". Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 75: 1–9. doi:10.1101/sqb.2010.75.039. PMID 21467139.

- ↑ Prahlad, V, Morimoto RI (Dec 2008). "Integrating the stress response: lessons for neurodegenerative diseases from C. elegans". Trends in Cell Biology. 19 (2): 52–61. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.002. PMID 19112021.

- ↑ Salamanca, HH; Fuda N; Shi H; Lis JT. (2011). "An RNA aptamer perturbs heat shock transcription factor activity in Drosophila melanogaster". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (15): 6729–6740. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr206. PMID 21576228.

- ↑ Salamanca, HH; Antonyak MA; Cerione RA; Shi H; Lis JT. (2014). "Inhibiting heat shock factor 1 in human cancer cells with a potent RNA aptamer.". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e96330. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096330. PMC 4011729

. PMID 24800749.

. PMID 24800749. - 1 2 Schuetz TJ, Gallo GJ, Sheldon L, Tempst P, Kingston RE (August 1991). "Isolation of a cDNA for HSF2: evidence for two heat shock factor genes in humans". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (16): 6911–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.16.6911. PMC 52203

. PMID 1871106.

. PMID 1871106.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Pfam and InterPro IPR000232