Vaginismus

| Vaginismus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Muscles included | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| ICD-10 | F52.5, N94.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 306.51 625.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 13701 |

| MedlinePlus | 001487 |

| MeSH | D052065 |

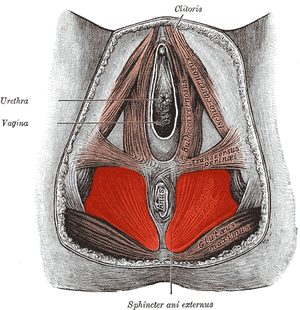

Vaginismus, sometimes called vaginism and genito-pelvic pain disorder, is a condition that affects a woman's ability to engage in vaginal penetration, including sexual intercourse, manual penetration, insertion of tampons or menstrual cups, and the penetration involved in gynecological examinations (pap tests). This is the result of an involuntary vaginal muscle spasm, which makes any kind of vaginal penetration painful or impossible. While there is a lack of evidence to definitively identify which muscle is responsible for the spasm, the pubococcygeus muscle, sometimes referred to as the "PC muscle", is most often suggested. Other muscles such as the levator ani, bulbocavernosus, circumvaginal, and perivaginal muscles have also been suggested.[1]

A woman with vaginismus does not consciously control the spasm. The vaginismic reflex can be compared to the response of the eye shutting when an object comes towards it. The severity of vaginismus, as well as the pain during penetration (including sexual penetration), varies from woman to woman.[2]

Causes

Primary vaginismus

A woman is said to have primary vaginismus when she is unable to have penetrative sex or experience vaginal penetration without pain. It is commonly discovered in teenage girls and women in their early twenties, as this is when many girls and young women in the Western world first attempt to use tampons, have penetrative sex, or undergo a Pap smear. Women with vaginismus may be unaware of the condition until they attempt vaginal penetration. A woman may be unaware of the reasons for her condition.[3]

A few of the main factors that may contribute to primary vaginismus include:

- a condition called vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, more or less synonymous with focal vaginitis, a so-called sub-clinical inflammation, in which no pain is perceived until some form of penetration is attempted

- urinary tract infections

- vaginal yeast infections

- sexual abuse, rape, other sexual assault, or attempted sexual abuse or assault

- knowledge of (or witnessing) sexual or physical abuse of others, without being personally abused

- domestic violence or similar conflict in the early home environment

- fear of pain associated with penetration, particularly the popular misconception of "breaking" the hymen upon the first attempt at penetration, or the idea that vaginal penetration will inevitably hurt the first time it occurs

- chronic pain conditions and harm-avoidance behaviour[4]

- any physically invasive trauma (not necessarily involving or even near the genitals)

- generalized anxiety

- stress

- negative emotional reaction towards sexual stimulation, e.g. disgust both at a deliberate level and also at a more implicit level[5]

- strict conservative moral education, which also can elicit negative emotions[6]

Primary vaginismus is often idiopathic.[7]

Vaginismus has been classified by Lamont[8] according to the severity of the condition. Lamont describes four degrees of vaginismus: In first degree vaginismus, the patient has spasm of the pelvic floor that can be relieved with reassurance. In second degree, the spasm is present but maintained throughout the pelvis even with reassurance. In third degree, the patient elevates the buttocks to avoid being examined. In fourth degree vaginismus (also known as grade 4 vaginismus), the most severe form of vaginismus, the patient elevates the buttocks, retreats and tightly closes the thighs to avoid examination. Pacik expanded the Lamont classification to include a fifth degree in which the patient experiences a visceral reaction such as sweating, hyperventilation, palpitations, trembling, shaking, nausea, vomiting, losing consciousness, wanting to jump off the table, or attacking the doctor.[9] The Lamont classification continues to be used to the present and allows for a common language among researchers and therapists.

A simplified and more versatile version of the classification includes symptoms that vary over four ranges. The first involves minor discomfort that may diminish during intercourse. In the second range, burning and tightness persist. In the third, entry and movement are painful, and in the fourth penetration is impossible and forced entry is extremely painful.

Although the pubococcygeus muscle is commonly thought to be the primary muscle involved in vaginismus, Pacik identified two additionally-involved spastic muscles in treated patients under sedation. These include the entry muscle (bulbocavernosum) and the mid-vaginal muscle (puborectalis). Spasm of the entry muscle accounts for the common complaint that patients often report when trying to have intercourse: "It's like hitting a brick wall".[3]

Secondary vaginismus

Secondary vaginismus occurs when a person who has previously been able to achieve penetration develops vaginismus. This may be due to physical causes such as a yeast infection or trauma during childbirth, while in some cases it may be due to psychological causes, or to a combination of causes. The treatment for secondary vaginismus is the same as for primary vaginismus, although, in these cases, previous experience with successful penetration can assist in a more rapid resolution of the condition. Peri-menopausal and menopausal vaginismus, often due to a drying of the vulvar and vaginal tissues as a result of reduced estrogen, may occur as a result of "micro-tears" first causing sexual pain then leading to vaginismus.[10]

Further factors that may contribute to either Secondary or Primary Vaginismus include:

- Fear of losing control

- Not trusting one’s partner

- Self-consciousness about body image

- Sexual abuse, rape, other sexual assault, or attempted sexual abuse or assault

- Misconceptions about sex or unattainable standards for sex from exaggerated sexual materials, such as pornography or abstinence

- Fear of vagina not being wide or deep enough / fear of partner’s penis being too large

- Undiscovered or denied sexuality (specifically, being asexual or lesbian)

- Undiscovered or denied feelings of being transgender (specifically, a trans man)

Treatment

A Cochrane review found little high quality evidence regarding the treatment of vaginismus in 2012.[11] Specifically it is unclear if systematic desensitisation is better than other measures including nothing.[11]

Psychological

According to Ward and Ogden's qualitative study on the experience of vaginismus (1994), the three most common contributing factors to vaginismus are fear of painful sex; the belief that sex is wrong or shameful (often the case with patients who had a strict religious upbringing); and traumatic early childhood experiences (not necessarily sexual in nature).

People with vaginismus are twice as likely to have a history of childhood sexual interference and held less positive attitudes about their sexuality, whereas no correlation was noted for lack of sexual knowledge or (non-sexual) physical abuse.[12]

Physical

Often, when faced with a person experiencing painful intercourse, a gynecologist will recommend Kegel exercises and provide some additional lubricants.[13][14][15][16] Strengthening the muscles that unconsciously tighten during vaginismus may be extremely counter-intuitive for some people. Also, vaginismus has not been shown to affect a person's ability to produce lubrication, thus providing lubricants may be extraneous to the actual condition. Treatment of vaginismus may involve the use Hegar dilators, (sometimes called vaginal trainers[17]) progressively increasing the size of the dilator inserted into the vagina.[18]

Neuromodulators

Botulinum toxin A (Botox) has been considered as a treatment option, under the idea of temporarily reducing the hypertonicity of the pelvic floor muscles. Although no random controlled trials have been done with this treatment, experimental studies with small samples have shown it to be effective, with sustained positive results through 10 months.[1][19] Similar in its mechanism of treatment, lidocaine has also been tried as an experimental option.[1][20]

Anxiolytics and antidepressants are other pharmacotherapies that have been offered to patients in conjunction with other psychotherapy modalities, or if these patients experience high levels of anxiety from their condition.[1] Results from these types of pharmacologic therapies have not been consistent.[1]

Epidemiology

True epidemiological studies of vaginismus have not been done, as diagnosis would require painful examinations that such women would most likely avoid. Data available is primarily reported statistics from clinical settings.[1]

A study of vaginismus in people in Morocco and Sweden found a prevalence of 6%. 18-20% of people in British and Australian studies were found to have manifest dyspareunia, while the rate among elderly British people was as low as 2%.[21]

A 1990 study of people presenting to sex therapy clinics found reported vaginismus rates of between 12% and 17%, while a random sampling and structured interview survey conducted in 1994 by National Health and Sexual Life Survey documented 10%-15% of people reported that in the past six months they had experienced pain during intercourse.[7]

The most recent study-based estimates of vaginismus incidence range from 5% to 47% of people presenting for sex therapy or complaining of sexual problems, with significant differences across cultures.[22] It seems likely that a society's expectations of person's sexuality may particularly impact on the people with the condition.[23]

Sexuality

General

If someone suspects they have vaginismus, sexual penetration is likely to remain painful or truly impossible until their vaginismus is addressed. This is a highly frustrating condition, as other people, including doctors, may speculate negatively on the origin or existence of their difficulties. Vaginismus does not mean that someone does not want intercourse or does not love their partner. People with vaginismus may be able to engage in a variety of other sexual activities, as long as penetration is avoided. Sexual partners of vaginismic people may come to believe that vaginismic people do not want to engage in penetrative sex at all, though this may not be true for most such people. There is currently no indication that vaginismus reduces the sexual drive or arousal of affected people, and as such it is likely that many vaginismic people wish to engage in penetrative sex to the same degree as unaffected people, but are deterred by the pain and emotional distress that accompanies each attempt. Psychological pressure to "perform" sexually or become aroused quickly with a partner can deter the person from future attempts and/or cause their vaginismus to become more severe.

Emotional experiences

A person who is interested in having (or, at minimum, willing to have) intercourse, and finds that their vagina responds with a reflex that makes intercourse impossible, is likely to experience a wide range of emotions, from amazement to grief to embarrassment. Some people may already have negative associations with their genitals, including fears that their genitals are ugly, dirty, or sinful.

These associations can lead to negative emotions arising during any kind of sexual expression, including masturbation, and these emotions can take time to process. Feelings of shame, inadequacy or a fear of being "defective" can be deeply troubling. If multiple attempts at penetration are made before treating vaginismus, it may lead to fear of sexual intercourse, and worsen the amount of pain experienced with each subsequent attempt. Relaxation, patience and self-acceptance are vital to a pleasurable experience.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lahaie, MA; Boyer, SC; Amsel, R; Khalifé, S; Binik, YM (Sep 2010). "Vaginismus: a review of the literature on the classification/diagnosis, etiology and treatment.". Women's health (London, England). 6 (5): 705–19. doi:10.2217/whe.10.46. PMID 20887170.

- ↑ Reissing, Elke; Yitzchak Binik; Samir Khalife (May 1999). "Does Vaginismus Exist? A Critical Review of the Literature". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 187 (5): 261–274. doi:10.1097/00005053-199905000-00001. PMID 10348080. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- 1 2 Pacik PT (December 2009). "Botox treatment for vaginismus". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 124 (6): 455e–6e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bf7f11. PMID 19952618.

- ↑ Borg, Charmaine; Peters, L. M.; Weijmar Schultz, W.; de Jong, P. J. (February 2012). "Vaginismus: Heightened Harm Avoidance and Pain Catastrophizing Cognitions". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 9 (2): 558–567. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02535.x.

- ↑ Borg, Charmaine; Peter J. De Jong; Willibrord Weijmar Schultz (June 2010). "Vaginismus and Dyspareunia: Automatic vs. Deliberate: Disgust Responsivity". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7 (6): 2149–2157. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01800.x.

- ↑ Borg, Charmaine; Peter J. de Jong; Willibrord Weijmar Schultz (Jan 2011). "Vaginismus and Dyspareunia: Relationship with General and Sex-Related Moral Standards". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (1): 223–231. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02080.x.

- 1 2 "Vaginismus". Sexual Pain Disorders and Vaginismus. Armenian Medical Network. 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Lamont, JA (1978). "Vaginismus". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 131 (6): 633–6. PMID 686049.

- ↑ Pacik, PT.; Cole, JB. (2010). When Sex Seems Impossible. Stories of Vaginismus and How You Can Achieve Intimacy. Odyne Publishing. pp. 40–7.

- ↑ Pacik, Peter (2010). When Sex Seems Impossible. Stories of Vaginismus & How You Can Achieve Intimacy. Manchester, NH: Odyne. pp. 8–16. ISBN 978-0-9830134-0-2.

- 1 2 Melnik, T; Hawton, K; McGuire, H (12 December 2012). "Interventions for vaginismus.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 12: CD001760. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001760.pub2. PMID 23235583.

- ↑ Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen D, Amsel R (2003). "Etiological correlates of vaginismus: sexual and physical abuse, sexual knowledge, sexual self-schema, and relationship adjustment". J Sex Marital Ther. 29 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1080/713847095. PMID 12519667.

- ↑ "When sex hurts – vaginismus". The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada. n.d.

- ↑ Herndon, Jaime (2012). "Vaginismus". Healthline. George Kruick, MD. Retrieved March 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Nazario, Brunilda, MD. (2012). "Women's Health: Vaginismus". WebMD. Retrieved March 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "When sex gives more pain than pleasure.". Harvard Health Publications. Harvard Health. 2012. Retrieved March 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ nhs, nhs (2015). "NHS Choices Vaginal Trainers to treat vaginismus". NHS Choices Vaginismus treatment. NHS.

- ↑ Doleys, Daniel (6 December 2012). Behavioral Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 377. ISBN 9781468440706.

- ↑ Pacik, PT. Vaginismus: A Review of Current Concepts and Treatment using Botox Injections, Bupivacaine Injections and Progressive Dilation Under Anesthesia. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Journal, doi:10.1007/s00266-011-9737-5

- ↑ Melnik, T; Hawton, K; McGuire, H (Dec 12, 2012). "Interventions for vaginismus.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 12: CD001760. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001760.pub2. PMID 23235583.

- ↑ Lewis RW, Fugl-Meyer KS, Bosch R, et al. (July 2004). "Epidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunction". J Sex Med. 1 (1): 35–9. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10106.x. PMID 16422981.

- ↑ see Reissing et al. 1999; Nusbaum 2000; Oktay 2003

- ↑ "Critical literature Review on Vaginismus". Critical literature Review on Vaginismus. Vaginismus Awareness Network. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

Further reading

- Crowley T, Richardson D, Goldmeier D (January 2006). "Recommendations for the management of vaginismus: BASHH Special Interest Group for Sexual Dysfunction". Int J STD AIDS. 17 (1): 14–8. doi:10.1258/095646206775220586. PMID 16409672.

- Nasab M., Farnoosh, Z. "Management of vaginismus with cognitive-behavioral therapy, self-finger approach: A study of 70 cases". Iranian J Basic Med Sci. 28 (2): 69–71.

- Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalifé S (May 1999). "Does vaginismus exist? A critical review of the literature". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 187 (5): 261–74. doi:10.1097/00005053-199905000-00001. PMID 10348080.

- van der Velde J, Everaerd W (2001). "The relationship between involuntary pelvic floor muscle activity, muscle awareness and experienced threat in women with and without vaginismus". Behav Res Ther. 39 (4): 395–408. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00007-3. PMID 11280339.

- Ward E., Ogden, J. (1994). "Experiencing Vaginismus: sufferers beliefs about causes and effects". Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 9 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1080/02674659408409565.