United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces[6] are the federal armed forces of the United States. They consist of the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard.[7] The President of the United States is the military's overall head, and helps form military policy with the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), a federal executive department, acting as the principal organ by which military policy is carried out.

From the time of its inception, the military played a decisive role in the history of the United States. A sense of national unity and identity was forged as a result of victory in the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War. Even so, the Founders were suspicious of a permanent military force. It played an important role in the American Civil War, where leading generals on both sides were picked from members of the United States military. Not until the outbreak of World War II did a large standing army become officially established. The National Security Act of 1947, adopted following World War II and during the Cold War's onset, created the modern U.S. military framework; the Act merged previously Cabinet-level Department of War and the Department of the Navy into the National Military Establishment (renamed the Department of Defense in 1949), headed by the Secretary of Defense; and created the Department of the Air Force and National Security Council.

The U.S. military is one of the largest militaries in terms of number of personnel. It draws its personnel from a large pool of paid volunteers; although conscription has been used in the past in various times of both war and peace, it has not been used since 1972. As of 2016, the United States spends about $580.3 billion annually to fund its military forces and Overseas Contingency Operations.[4] Put together, the United States constitutes roughly 40 percent of the world's military expenditures. For the period 2010–14, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) found that the United States was the world's largest exporter of major arms, accounting for 31 per cent of global shares. The United States was also the world's eighth largest importer of major weapons for the same period.[8] The U.S. military has significant capabilities in both defense and power projection due to its large budget, resulting in advanced and powerful equipment, and its widespread deployment of force around the world, including about 800 military bases in foreign locations.[9]

History

The history of the U.S. military dates to 1775, even before the Declaration of Independence marked the establishment of the United States. The Continental Army, Continental Navy, and Continental Marines were created in close succession by the Second Continental Congress in order to defend the new nation against the British Empire in the American Revolutionary War.

These forces demobilized in 1784 after the Treaty of Paris ended the War for Independence. The Congress of the Confederation created the United States Army on 3 June 1784, and the United States Congress created the United States Navy on 27 March 1794, and the United States Marine Corps on 11 July 1798. All three services trace their origins to the founding of the Continental Army (on 14 June 1775), the Continental Navy (on 13 October 1775) and the Continental Marines (on 10 November 1775), respectively. The 1787 adoption of the Constitution gave the Congress the power to "raise and support armies", "provide and maintain a navy", and to "make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces", as well as the power to declare war. The United States President is the U.S. military's commander-in-chief.

Rising tensions at various times with Britain and France and the ensuing Quasi-War and War of 1812 quickened the development of the U.S. Navy (established 13 October 1775) and the United States Marine Corps (established 10 November 1775). The U.S. Coast Guard dates its origin to the founding of the Revenue Cutter Service on 4 August 1790; that service merged with the United States Life-Saving Service in 1915 to establish the Coast Guard. The United States Air Force was established as an independent service on 18 September 1947; it traces its origin to the formation of the Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps in 1907 and was part of the Army before becoming an independent service.

The reserve branches formed a military strategic reserve during the Cold War, to be called into service in case of war.[10][11][12] Time magazine's Mark Thompson has suggested that with the War on Terror, the reserves deployed as a single force with the active branches and America no longer has a strategic reserve.[13][14][15]

Command structure

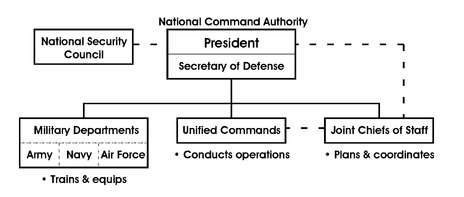

Command over the armed forces is established in the United States Constitution. The sole power of command is vested in the President by Article II as Commander-in-Chief. The Constitution also allows for the creation of "executive Departments" headed "principal officers" whose opinion the President can require. This allowance in the Constitution formed the basis for creation of the Department of Defense in 1947 by the National Security Act. The Defense Department is headed by the Secretary of Defense, who is a civilian and member of the Cabinet. The Defense Secretary is second in the military's chain of command, just below the President, and serves as the principal assistant to the President in all defense-related matters.[16] Together, the President and the Secretary of Defense comprise the National Command Authority, which by law, is the ultimate lawful source of military orders.[17]

To coordinate military strategy with political affairs, the President has a National Security Council headed by the National Security Advisor. The collective body has only advisory power to the President, but several of the members who statutorily comprise the council (the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Energy, and the Secretary of Defense) possess executive authority over their own departments.[18]

Just as the President and the Secretary of Defense are in charge of the entire military establishment, maintaining civilian control of the military, so too are each of the Defense Department's constitutive military departments headed by civilians. The five branches are organized into three departments, each with civilian heads. The Department of the Army is headed by the Secretary of the Army, the Department of the Navy is headed by the Secretary of the Navy, and the Department of the Air Force is headed by the Secretary of the Air Force. The Marine Corps is organized under the Department of the Navy. The Coast Guard is not under the administration of the Defense Department, but the Department of Homeland Security and receives its operational orders from the Secretary of Homeland Security. However, the Coast Guard may be transferred to the Department of the Navy by the President or Congress during a time of war, thereby placing it within the Defense Department.[19]

The President, Secretary of Defense, and other senior executive officials are advised by a seven-member Joint Chiefs of Staff, which is headed by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the highest-ranking officer in the United States military, and the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[20] The rest of the body is composed of the heads of each of the Defense Department's service branches (the Chief of Staff of the Army, the Chief of Naval Operations, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force) as well as the Chief of the National Guard Bureau. Although commanding one of the five military branches, the Commandant of the Coast Guard is not a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Despite being composed of the highest-ranking officers in each of the respective branches, the Joint Chiefs of Staff does not possess operational command authority. Rather, the Goldwater-Nichols Act charges them only with advisory power.[21]

All of the branches work together during operations and joint missions in Unified Combatant Commands, under the authority of the Secretary of Defense with the exception of the Coast Guard. Each of the Unified Combatant Commands is headed by a Combatant Commander, a senior commissioned officer who exercises supreme command authority per 10 U.S.C. § 164 over all of the forces, regardless of branch, within his geographical or functional command. By statute, the chain of command flows from the President to the Secretary of Defense to each of the Combatant Commanders.[22] In practice, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff often acts as an intermediary between the Secretary of Defense and the Combatant Commanders.

All five armed services are among the seven uniformed services of the United States, the two others being the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps (under the Department of Health and Human Services) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Commissioned Officer Corps (under the Department of Commerce).

Budget

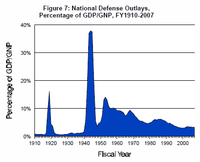

The United States has the world's largest military budget. In the fiscal year 2016, $580.3 billion in funding were enacted for the Department of Defense (DoD) and for "Overseas Contingency Operations" in the War on Terrorism.[4] Outside of direct DoD spending, the United States spends another $218 to $262 billion each year on other defense-related programs, such as Veterans Affairs, Homeland Security, nuclear weapons maintenance, and the State Department.

By service, $146.9 billion was allocated for the Army, $168.8 billion for the Navy and Marine Corps, $161.8 billion for the Air Force and $102.8 billion for defense-wide spending.[4] By function, $138.6 billion was requested for personnel, $244.4 billion for operations and maintenance, $118.9 billion for procurement, $69.0 billion for research and development, $1.3 billion for revolving and management funds, $6.9 billion for military construction, and $1.3 billion for family housing.[4]

In FY 2009, major defense programs saw continued funding:

- $4.1 billion was requested for the next-generation fighter, F-22 Raptor, which was to roll out an additional 20 planes in 2009

- $6.7 billion was requested for the F-35 Lightning II, which is still under development, but 16 planes were slated to be built

- The Future Combat System program is expected to see $3.6 billion for its development.

- A total of $12.3 billion was requested for missile defense, including Patriot CAP, PAC-3 and SBIRS-High.

Loren Thompson, a defense analyst with the Lexington Institute, has blamed the "vast sums of money" squandered on cutting-edge technology projects that were then canceled on shortsighted political operatives who lack a long-term perspective in setting requirements. The result is that the number of items bought under a given program are cut. The total development costs of the program are divided over fewer platforms, making the per-unit cost seem higher and so the numbers are cut again and again in a death spiral.[23] Although the United States was the world's biggest exporter of major weapons in 2010–14, the US was also the world's eight biggest importer during the same period. US arms imports increased by 21 per cent between 2005–2009 and 2010–14.[8]

Cost containment measures in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Obama administration's energy policy will play critical determining roles because health care and fuel costs are the two fastest-growing segments of the defense budget.[24][25]

Personnel

The projected active duty end strength in the armed forces for FY 2017 was 1,281,900 people,[4] with an additional 801,200 people in the seven reserve components.[4] It is an all-volunteer military, but conscription through the Selective Service System can be enacted at the President's request and Congress' approval. All males ages 18 through 25 who are living in the United States are required to register with the Selective Service for a potential future draft.

The U.S. military is the world's second largest, after China's People's Liberation Army, and has troops deployed around the globe.

From 1776 until September 2012, a total of 40 million people have served in the United States Armed Forces.[26]

The FY 2017 DoD budget request[4] plan calls for an active duty end strength of 1,281,900, a decrease of 19,400 from the 2016 baseline as a result of decrements in the Army (15,000 fewer personnel) and Navy (4,400 fewer personnel) strength. The budget request also calls for a reserve component end strength of 801,200, a decrease of 9,800 personnel.

As in most militaries, members of the U.S. military hold a rank, either that of officer, warrant, or enlisted, to determine seniority and eligibility for promotion. Those who have served are known as veterans. Rank names may be different between services, but they are matched to each other by their corresponding paygrade.[27] Officers who hold the same rank or paygrade are distinguished by their date of rank to determine seniority, while officers who serve in certain positions of office of importance set by law, outrank all other officers in active duty of the same rank and paygrade, regardless of their date of rank.[28] Currently, only one in four persons in the United States of the proper age meet the moral, academic and physical standards for military service.[29]

Personnel in each service

2010 Demographic Reports and end strengths for reserve components.[4][30][31] (should be updated using 2011 Demographic Reports[32] and Dec.2011 DMDC military personnel data[33])

| Component | Military | Enlisted | Officer | Male | Female | Civilian |

| | 541,291 | 438,670 | 98,126 | 465,784 | 75,507 | 299,644 |

| | 195,338 | 173,474 | 21,864 | 181,845 | 13,493 | 20,484 |

| | 317,237 | 260,253 | 52,546 | 265,852 | 51,385 | 179,293 |

| | 333,772 | 265,519 | 64,290 | 270,462 | 63,310 | 174,754 |

| | 42,357 | 35,567 | 6,790 | 7,057 | ||

| Total Active | 1,429,995 | 1,137,916 | 236,826 | 1,219,510 | 210,485 | |

| | 342,000 | |||||

| | 198,000 | |||||

| | 38,900 | |||||

| | 57,400 | |||||

| | 105,500 | |||||

| | 69,200 | |||||

| | 7,000 | |||||

| Total Reserves | 818,000 | |||||

| Other DoD Personnel | 108,833 |

These numbers do not take into account the use of Private Military and Private Security Companies (PSCs). Quarterly PSC census reports are available for United States Central Command (USCENTCOM)'s area of operations—i.e., Iraq and Afghanistan.[34] As of March 2011, there were 18,971 private security contractor (PSC) personnel in Afghanistan working for DoD; in Iraq, there were 9,207 PSC personnel, down from a high of 15,279 in June 2009.[35] As of October 2012, in Afghanistan, there were 18,914 PSC personnel working for DoD; in Iraq, there were 2,116 PSC personnel.[36] The total number of DoD contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan was more than 137,400; reported PSCs were only a part of the number.

Personnel stationing

Overseas

As of 31 December 2010, U.S. armed forces were stationed in 150 countries; the number of non-contingent deployments per country ranges from 1 in Suriname to over 50,000 in Germany.[37] Some of the largest deployments are: 103,700 in Afghanistan, 52,440 in Germany (see list), 35,688 in Japan (USFJ), 28,500 in South Korea (USFK), 9,660 in Italy, and 9,015 in the United Kingdom. These numbers change frequently due to the regular recall and deployment of units.

Altogether, 77,917 military personnel are located in Europe, 141 in the former Soviet Union, 47,236 in East Asia and the Pacific, 3,362 in North Africa, the Near East, and South Asia, 1,355 in sub-Saharan Africa and 1,941 in the Western Hemisphere excluding the United States itself.

Within the United States

Including U.S. territories and ships afloat within territorial waters

As of 31 December 2009, a total of 1,137,568 personnel were on active duty within the United States and its territories (including 84,461 afloat).[38] The vast majority (941,629 personnel) were stationed at bases within the contiguous United States. There were an additional 37,245 in Hawaii and 20,450 in Alaska; 84,461 were at sea, 2,972 in Guam, and 179 in Puerto Rico.

Types of personnel

Enlisted

Prospective service members are often recruited from high school or college, the target age ranges being 18–35 in the Army, 18–28 in the Marine Corps, 18–34 in the Navy, 18–39 in the Air Force, and 18–27 (up to age 32 if qualified for attending guaranteed "A" school) in the Coast Guard. With the permission of a parent or guardian, applicants can enlist at age 17 and participate in the Delayed Entry Program (DEP), in which the applicant is given the opportunity to participate in locally sponsored military activities, which can range from sports to competitions led by recruiters or other military liaisons (each recruiting station's DEP varies).

After enlistment, new recruits undergo basic training (also known as "boot camp" in the Marine Corps, Navy and Coast Guard), followed by schooling in their primary Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) or rating at any of the numerous training facilities around the world. Each branch conducts basic training differently. Marines send all non-infantry MOS's to an infantry skills course known as Marine Combat Training prior to their technical schools. Air Force Basic Military Training graduates attend Technical Training and are awarded an Air Force Specialty Code (AFSC) at the apprentice (3) skill level. All Army recruits undergo Basic Combat Training (BCT), followed by Advanced Individual Training (AIT), with the exceptions of cavalry scouts, infantry, armor, combat engineers, and military police recruits who go to One Station Unit Training (OSUT), which combines BCT and AIT. The Navy sends its recruits to Recruit Training and then to "A" schools to earn a rating. The Coast Guard's recruits attend basic training and follow with an "A" school to earn a rating.

Initially, recruits without higher education or college degrees will hold the pay grade of E-1, and will be elevated to E-2 usually soon after basic training. Different services have different incentive programs for enlistees, such as higher initial ranks for college credit, being an Eagle Scout, and referring friends who go on to enlist as well. Participation in DEP is one way recruits can achieve rank before their departure to basic training.

There are several different authorized pay grade advancement requirements in each junior-enlisted rank category (E-1 to E-3), which differ by service. Enlistees in the Army can attain the initial pay grade of E-4 (specialist) with a four-year degree, but the highest initial pay grade is usually E-3 (members of the Army Band program can expect to enter service at the grade of E-4). Promotion through the junior enlisted ranks occurs after serving for a specified number of years (which, however, can be waived by the soldier's chain of command), a specified level of technical proficiency, or maintenance of good conduct. Promotion can be denied with reason.

Non-commissioned officers

With very few exceptions, becoming a non-commissioned officer (NCO) in the U.S. military is accomplished by progression through the lower enlisted ranks. However, unlike promotion through the lower enlisted tier, promotion to NCO is generally competitive. NCO ranks begin at E-4 or E-5, depending upon service, and are generally attained between three and six years of service. Junior NCOs function as first-line supervisors and squad leaders, training the junior enlisted in their duties and guiding their career advancement.

While considered part of the non-commissioned officer corps by law, senior non-commissioned officers (SNCOs) referred to as chief petty officers in the Navy and Coast Guard, or staff non-commissioned officers in the Marine Corps, perform duties more focused on leadership rather than technical expertise. Promotion to the SNCO ranks, E-7 through E-9 (E-6 through E-9 in the Marine Corps) is highly competitive. Personnel totals at the pay grades of E-8 and E-9 are limited by federal law to 2.5 percent and 1 percent of a service's enlisted force, respectively. SNCOs act as leaders of small units and as staff. Some SNCOs manage programs at headquarters level and a select few wield responsibility at the highest levels of the military structure. Most unit commanders have a SNCO as an enlisted advisor. All SNCOs are expected to mentor junior commissioned officers as well as the enlisted in their duty sections. The typical enlistee can expect to attain SNCO rank after 10 to 16 years of service.

Each of the five services employs a single Senior Enlisted Advisor at departmental level. This individual is the highest ranking enlisted member within that respective service and functions as the chief advisor to the service secretary, service chief of staff, and Congress on matters concerning the enlisted force. These individuals carry responsibilities and protocol requirements equivalent to three-star general and flag officers. They are as follows:

- Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chairman

- Sergeant Major of the Army

- Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps

- Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy

- Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force

- Master Chief Petty Officer of the Coast Guard

Warrant officers

Additionally, all services except for the Air Force have an active warrant-officer corps. Above the rank of Warrant Officer One, these officers may also be commissioned, but usually serve in a more technical and specialized role within units. More recently though they can also serve in more traditional leadership roles associated with the more recognizable officer corps. With one notable exception (Army helicopter and fixed-wing pilots), these officers ordinarily have already been in the military often serving in senior NCO positions in the field in which they later serve as a Warrant Officer as a technical expert. Most Army pilots have served some enlisted time. It is also possible to enlist, complete basic training, go directly to the Warrant Officer Candidate school at Fort Rucker, Alabama, and then on to flight school.

Warrant officers in the U.S. military garner the same customs and courtesies as commissioned officers. They may attend the officer's club, receive a command and are saluted by junior warrant officers and all enlisted service members.

The Air Force ceased to grant warrants in 1959 when the grades of E-8 and E-9 were created. Most non-flying duties performed by warrant officers in other services are instead performed by senior NCOs in the Air Force.

Commissioned officers

Officers receive a commission in one of the branches of the U.S. military through one of the following routes.

- Service academies (United States Military Academy in West Point, New York; United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland; United States Air Force Academy at Colorado Springs, Colorado; the United States Coast Guard Academy at New London, Connecticut; and the United States Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, New York)

- Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC)

- Officer Candidate School (OCS) (Officer Training School (OTS) in the Air Force): This can be through active-duty academies, or through state-run academies in the case of the Army National Guard.

- Direct commission: civilians who have special skills that are critical to sustaining military operations and supporting troops may receive direct commissions. These officers occupy leadership positions in law, medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nurse corps, intelligence, supply-logistics-transportation, engineering, public affairs, chaplain corps, oceanography, and others.

- Battlefield commission: Under certain conditions, enlisted personnel who have skills that separate them from their peers can become officers by direct commissioning of a commander so authorized to grant them. This type of commission is rarely granted and is reserved only for the most exceptional enlisted personnel; it is done on an ad hoc basis, typically only in wartime. No direct battlefield commissions have been awarded since the Vietnam War. The Navy and Air Force do not employ this commissioning path.

- Limited Duty Officer: Due to the highly technical nature of some officer billets, the Marine Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard employ a system of promoting proven senior enlisted members to the ranks of commissioned officers. They fill a need that is similar to, but distinct from that filled by Warrant Officers (to the point where their accession is through the same school). While Warrant Officers remain technical experts, LDOs take on the role of a generalist, like that of officers commissioned through more traditional sources. LDOs are limited, not by their authority, but by the types of billets they are allowed to fill. However, in recent times, they have come to be used more and more like their more-traditional counterparts.

Officers receive a commission assigning them to the officer corps from the president with the Senate's consent. To accept this commission, all officers must take an oath of office.

Through their careers, officers usually will receive further training at one or a number of the many staff colleges.

Company grade officers in pay grades O-1 through O-3 (known as "junior" officers in the Navy and Coast Guard) function as leaders of smaller units or sections of a unit, typically with an experienced SNCO (or CPO in the Navy and Coast Guard) assistant and mentor.

Field grade officers in pay grades O-4 through O-6 (known as "senior" officers in the Navy and Coast Guard) lead significantly larger and more complex operations, with gradually more competitive promotion requirements.

General officers, or flag officers in the Navy and Coast Guard, serve at the highest levels and oversee major portions of the military mission.

Five-star ranking

These are ranks of the highest honor and responsibility in the armed forces, but they are almost never given during peacetime and only a very small number of officers during wartime have held a five-star rank:

No corresponding rank exists for the Marine Corps or the Coast Guard. As with three- and four-star ranks, Congress is the approving authority for a five-star rank confirmation.

The rank of General of the Armies is considered senior to General of the Army, but was never held by active duty officers at the same time as persons who held the rank of General of the Army. It has been held by two people: John J. Pershing who received the rank in 1919 after World War I, and George Washington who received it posthumously in 1976 as part of the American Bicentennial celebrations. Pershing, appointed to General of the Armies in active duty status for life, was still alive at the time of the first five-star appointments during World War II, and was thereby acknowledged as superior in grade by seniority to any World War II–era Generals of the Army. George Washington's appointment by Public Law 94-479 to General of the Armies of the United States was established by law as having "rank and precedence over all other grades of the Army, past or present", making him not only superior to Pershing, but superior to any grade in the Army in perpetuity.

In the Navy, the rank of Admiral of the Navy theoretically corresponds to that of General of the Armies, though it was never held by active-duty officers at the same time as persons who held the rank of Fleet Admiral. George Dewey is the only person to have ever held this rank. After the establishment of the rank of Fleet Admiral in 1944, the Department of the Navy specified that the rank of Fleet Admiral was to be junior to the rank of Admiral of the Navy. However, since Dewey died in 1917 before the establishment of the rank of Fleet Admiral, the six-star rank has not been totally confirmed.

Role of women

The Woman's Army Auxiliary Corps was established in the United States in 1942. Women saw combat during World War II, first as nurses in the Pearl Harbor attacks on 7 December 1941. The Woman's Naval Reserve and Marine Corps Women's Reserve were also created during this conflict. In 1944 WACs arrived in the Pacific and landed in Normandy on D-Day. During the war, 67 Army nurses and 16 Navy nurses were captured and spent three years as Japanese prisoners of war. There were 350,000 American women who served during World War Two and 16 were killed in action; in total, they gained over 1,500 medals, citations and commendations. Virginia Hall, serving with the Office of Strategic Services, received the second-highest US combat award, the Distinguished Service Cross, for action behind enemy lines in France.

After World War II, demobilization led to the vast majority of serving women being returned to civilian life. Law 625, The Women's Armed Services Act of 1948, was signed by President Truman, allowing women to serve in the armed forces in fully integrated units during peace time, with only the WAC remaining a separate female unit. During the Korean War of 1950–1953 many women served in the Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals, with women serving in Korea numbering 120,000 during the conflict. During the Vietnam War, 600 women served in the country as part of the Air Force, along with 500 members of the WAC, and over 6,000 medical personnel and support staff. The Ordnance Corps began accepting female missile technicians in 1974,[40] and female crewmembers and officers were accepted into Field Artillery missile units.[41][42]

In 1974, the first six women aviators earned their wings as Navy pilots. The Congressionally mandated prohibition on women in combat places limitations on the pilots' advancement,[43] but at least two retired as captains.[44] In 1989, Capt Linda L. Bray, 29, became the first woman to command American soldiers in battle, during the invasion of Panama. The 1991 Gulf War proved to be the pivotal time for the role of women in the American Armed forces to come to the attention of the world media. There are many reports of women engaging enemy forces during the conflict.[45]

In the 2000s, women can serve on American combat ships, including in command roles. They are permitted to serve on submarines.[46] They are not permitted to participate in special forces programs such as Navy SEALs. Women enlisted soldiers are barred from serving in Infantry, Special Forces, however female enlisted members and officers can hold staff positions in every branch of the Army except infantry and armor. Women can however serve on the staffs of infantry and armor units at Division level and above, and be members of Special Operations Forces. Women can fly military aircraft and make up 2% of all pilots in the U.S. Military. In 2003, Major Kim Campbell was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for landing her combat damaged A-10 Thunderbolt II with no hydraulic control and only one functional engine after being struck by hostile fire over Baghdad.

On 3 December 2015, United States of America Defense Secretary, Ashton Carter, announced that all military combat jobs would become available to women.[47] This gave women access to the roughly 10% of military jobs which were previously closed off due to their combat nature.[48] The decision gave military services until January 2016 to seek exceptions to the rule if they believe that certain jobs, such as machine gunner's, should be restricted to men only.[49] These restrictions were due in part to prior studies which stated that mixed gender units are less capable in combat.[50] Physical requirements for all jobs remained unchanged, though.[50] Many women believe this will allow for them to improve their positions in the military since most high-ranking officers start in combat positions. Since women are now available to work in any position in the military, female entry into the draft has been proposed.[51]

Sergeant Leigh Ann Hester became the first woman to receive the Silver Star, the third-highest US decoration for valor, for direct participation in combat. In Afghanistan, Monica Lin Brown was presented the Silver Star for shielding wounded soldiers with her body.[52] In March 2012, the U.S. military had two women, Ann E. Dunwoody and Janet C. Wolfenbarger, with the rank of four-star general.[53][54] In 2016, General Lori Robinson became the first female officer to command a major Unified Combatant Command (USNORTHCOM) in the history of the United States Armed Forces.[55]

Order of precedence

Under current Department of Defense regulation, the various components of the Armed Forces have a set order of seniority. Examples of the use of this system include the display of service flags, placement of Soldiers, Marines, Sailors, and Airmen in formation, etc. When the Coast Guard shall operate as part of the Navy, the cadets, United States Coast Guard Academy, the United States Coast Guard, and the Coast Guard Reserve shall take precedence, respectively, after the midshipmen, United States Naval Academy; the United States Navy; and Navy Reserve.[56]

- Cadets, U.S. Military Academy

- Midshipmen, U.S. Naval Academy

- Cadets, U.S. Coast Guard Academy (when part of the Navy)

- Cadets, U.S. Air Force Academy

- Cadets, U.S. Coast Guard Academy (when part of the Department of Homeland Security)

- Midshipmen, U.S. Merchant Marine Academy

- United States Army

- United States Marine Corps

- United States Navy

- United States Coast Guard (when part of the Navy)

- United States Air Force

- United States Coast Guard (when part of Homeland Security)

- Army National Guard of the United States

- United States Army Reserve

- United States Marine Corps Reserve

- United States Navy Reserve

- United States Coast Guard Reserve (when part of the Navy)

- Air National Guard of the United States

- United States Air Force Reserve

- United States Coast Guard Reserve (when part of Homeland Security)

- Other training and auxiliary organizations of the Army, Marine Corps, Merchant Marine, Civil Air Patrol, and Coast Guard Auxiliary, as in the preceding order. However, the Civil Air Patrol actually predates the Air Force as an independent service. The CAP was constituted through the Administrative Order 9 of 1 December 1941 and operated under the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II. The CAP became the official civilian auxiliary of the newly independent USAF with the enactment of Public Law 80-557 on 26 May 1948.

Note: While the U.S. Navy is "older" than the Marine Corps,[57] the Marine Corps takes precedence due to previous inconsistencies in the Navy's birth date. The Marine Corps has recognized its observed birth date on a more consistent basis. The Second Continental Congress is considered to have established the Navy on 13 October 1775 by authorizing the purchase of ships, but did not actually pass the "Rules for the Regulation of the Navy of the United Colonies" until 27 November 1775.[58] The Marine Corps was established by act of said Congress on 10 November 1775. The Navy did not officially recognize 13 October 1775 as its birth date until 1972, when then–Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo Zumwalt authorized it to be observed as such.[57]

See also

- Awards and decorations of the United States military

- Full-spectrum dominance

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of currently active United States military land vehicles

- List of currently active United States military watercraft

- Military expression

- Military justice

- National Guard

- Public opinion of the military

- Servicemembers' Group Life Insurance

- Sexual orientation and gender identity in the United States military

- State Defense Force

- TRICARE – Health care plan for the U.S. uniformed services

- United States military casualties of war

- United States military veteran suicide

- United States Service academies

- Women in the United States Army

- Women in the United States Marines

- Women in the United States Navy

- Women in the United States Air Force

- Women in the United States Coast Guard

References

- ↑ "United States Army". Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ↑ "Contact Us: Frequently Asked Questions - airforce.com". airforce.com. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Plan Your Next Move to Become a Coast Guard Member". Enlisted Opportunities. U.S. Coast Guard. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Department of Defense (DoD) Releases Fiscal Year 2017 President's Budget Proposal". U.S. Department of Defense. 9 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2015" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ↑ As stated on the official U.S. Navy website, "armed forces" is capitalized when preceded by "United States" or "U.S.".

- ↑ 10 U.S.C. § 101(a)(4)

- 1 2 "Trends in International Arms Transfer, 2014". www.sipri.org. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ http://www.acq.osd.mil/ie/download/bsr/CompletedBSR2015-Final.pdf Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Greenhill, Jim. "Casey: National Guard's Future Not in Strategic Reserve." National Guard Bureau, 3 August 2010.

- ↑ Roscoe Bartlett "Bartlett Opening Statement for Hearing on Army and Air Force National Guard and Reserve Component Equipment Posture." House Armed Services Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces, 1 April 2011.

- ↑ "Statement by General Craig R. McKinley, Chief National Guard Bureau, Before the Senate Appropriations Committee Subcommittee on Defense, Second Session, 111th Congress". Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ↑ Thompson, Mark. "On Guard: A Seventh Member for the Joint Chiefs?" Time, 13 September 2011.

- ↑ Friedman, George. "Frittering Away the Strategic Reserve". The Officer, September 2008.

- ↑ "GAO-06-170T: Army National Guard's Role, Organization, and Equipment Need to Be Reexamined" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. 20 October 2005. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ↑ Title 10 of the United States Code §113

- ↑ "World-Wide Military Command and Control System (WWMCCS), Department of Defense Directive 5100.30". Issued by Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard on December 2, 1971.

- ↑ "National Security Council". www.whitehouse.gov. The White House. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ↑ The United States Coast Guard has both military and law enforcement functions. Title 14 of the United States Code provides that "The Coast Guard as established 28 January 1915, shall be a military service and a branch of the armed forces of the United States at all times." Coast Guard units, or ships of its predecessor service, the Revenue Cutter Service, have seen combat in every war and armed conflict of the United States since 1790, including the Iraq War.

- ↑ "Organization Chart of the Joint Chiefs of Staff" (pdf). JCS Leadership. Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ 10 USC 152. Chairman: appointment; grade and rank

- ↑ Watson, Cynthia A. (2010). Combatant Commands: Origins, Structure, and Engagements. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-35432-8.

- ↑ Thompson, Loren B. "How To Waste $100 Billion: Weapons That Didn't Work Out." Forbes Magazine, 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Miles, Donna. "Review to Consider Consequences of Budget Cuts." American Forces Press Service, 21 April 2011.

- ↑ "White House Forum on Energy Security." The White House, 26 April 2011.

- ↑ Scott McGaugh (16 February 2013). "Learning from America's Wars, Past and Present U.S. Battlefield Medicine has come". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ For example, a lieutenant general in the Army is equivalent to a vice admiral in that Navy since they both carry a paygrade of O-9.

- ↑ "Department of Defence Instruction 1310.01: Rank and Seniority of Commissioned Officers" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. 6 May 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ↑ Barber, Barrie. "Military looking for more tech-savvy recruits." Springfield News-Sun. 11 March 2012.

- ↑ "tbc". U.S. Department of Defense. 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ↑ "Active Duty Military Personnel by Rank/Grade" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ↑ "tbc". U.S. Department of Defense. 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ "tbc". U.S. Department of Defense. 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ "CONTRACTOR SUPPORT OF U.S. OPERATIONS IN THE USCENTCOM AREA OF RESPONSIBILITY TO INCLUDE IRAQ AND AFGHANISTAN" (PDF). US Secretary of Defense. 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ "DOD's Use of PSCs in Afghanistan and Iraq" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ "CONTRACTOR SUPPORT OF U.S. OPERATIONS IN THE USCENTCOM AREA OF RESPONSIBILITY TO INCLUDE IRAQ AND AFGHANISTAN" (DOC). US Secretary of Defense. 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ "Active duty military personnel strengths by regional area and by country" (PDF). U.S. Department of Defense. 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ↑ "Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Michael G. (27 September 2005). "First All-female Crew Flies Combat Mission". DefendAmerica.mil. United States Department of Defense. Retrieved 2 July 2006.

- ↑ "The Women of Redstone Arsenal". United States Army. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ Busse, Charlane (July 1978). "First women join Pershing training" (PDF). Field Artillery Journal. United States Army Field Artillery School: 40. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ↑ "The Journal interviews: 1LT Elizabeth A. Tourville" (PDF). Field Artillery Journal. United States Army Field Artillery School: 40–43. November 1978. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ↑ https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1356&dat=19840823&id=kdgTAAAAIBAJ&sjid=iwYEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6981,4703933|Ocala Star-Banner 23 August 1984.

- ↑ http://www.history.navy.mil/nan/backissues/1990s/1997/mj97/ppp.pdf|Naval Aviation News, May–June 1997.

- ↑ http://userpages.aug.com/captbarb/femvetsds.html

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/apr/29/us-navy-submarines-women US navy lifts ban on women submariners (The Guardian (UK), 29 April 2010).

- ↑ Baldor, Lolita. "Carter Telling Military to Open all Combat Jobs to Women". Military.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ Lamothe, Dan. "Washington Post". In historic decision, Pentagon chief opens all jobs in combat units to women. Washington Post. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Connley, Courtney. "Black Enterprise". Breaking Barriers: U.S. Military Opens up Combat Jobs to Women. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- 1 2 Tilghman, Andrew. "Military Times". All combat jobs open to women in the military. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "TIMES". Now Women Should Register For The Draft. TIMES. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Clare, Micah E. (24 March 2008), "Face of Defense: Woman Soldier Receives Silver Star", American Forces Press Service

- ↑ Military's First Female Four-Star General

- ↑ http://militarytimes.com/blogs/offduty-plus/2012/03/28/wolfenbarger-confirmed-as-1st-female-af-4-star/

- ↑ "Carter Names First Female Combatant Commander". U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ 10 U.S.C. § 118 (prior section 133b renumbered in 1986); DoD Directive 1005.8 dated 31 October 77 and AR 600-25

- 1 2 Naval History & Heritage Command. "Precedence of the U.S. Navy and the Marine Corps", U.S. Department of the Navy. 11 February 2016

- ↑ "Rules for the Regulation of the Navy of the United Colonies of North-America". Naval Historical Center. Department of the Navy. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Military of the United States. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: United States Armed Forces |

- Official U.S. Department of Defense website

- Global Security on U.S. Military Operations

- Department of Defense regulation detailing Order of precedence: DoD Directive 1005.8, 31 October 1977 and also in law at Title 10, United States Code, Section 133.

- Army regulation detailing Order of Precedence: AR 840-10, 1 November 1998

- Marine Corps regulation on Order of Precedence: NAVMC 2691, Marine Corps Drill and Ceremonies Manual, Part II, Ceremonies, Chapter 12-1.

- Navy regulation detailing Order of Precedence: U.S. Navy Regulations, Chapter 12, Flags, Pennants, Honors, Ceremonies and Customs.

- Air Force regulation detailing Order of Precedence: AFMAN 36-2203, Drill and Ceremonies, 3 June 1996, Chapter 7, Section A.

- Types of Military Service - Today's Military