The Unsex'd Females

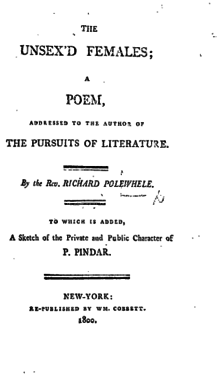

Title page from the 1800 New York edition | |

| Author | Richard Polwhele |

|---|---|

| Country | Britain |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | William Cobbett (orig. pub. Cadell and Davies) |

Publication date | 1798; rpt. 1800 |

The Unsex'd Females, a Poem (1798), by Richard Polwhele, is a polemical intervention into the public debates over the role of women at the end of the 18th century. The poem is primarily concerned with what Polwhele characterizes as the encroachment of radical French political and philosophical ideas into British society, particularly those associated with the Enlightenment. These subjects come together, for Polwhele, in the revolutionary figure of Mary Wollstonecraft.

The poem is of interest to those interested in the history of women, as well as revolutionary politics, for several reasons: it demonstrates the continued viability of the tradition of misogynist literature; it is an example of the British backlash against the ideals of the French Revolution; it is representative of the strategic conflation of women writers with revolutionary ideals during this period;[1] and it helps illuminate the obstacles faced by women writers at the end of the 18th century.

Historical context

Responding to women authors according to presumptions about their sexuality has a long history; a comparison between the critical reputations of Aphra Behn and Katherine Philips, more than a century earlier, is instructive here as these two writers were virtually symbolic of the choices available to women writers in the 18th century: Behn's reputation as "shady and amorous"[2] continued well into the 20th century, whereas Philips — known as "The Matchless Orinda" — was considered an exemplar of proper femininity.[3] Polwhele is hardly original in his opposition of "proper" and "improper" women writers and his criticism of Wollstonecraft is focused on her troubled and unconventional life as described in the frank biography by William Godwin[4] as much as on her writing.

The Unsex'd Female is complicated, however, by the tumultuous political situation at the time of its publication. The American Revolution had occurred only two decades earlier, the events of the French Revolution were even more recent, and the Haitian Revolution, the most successful of the African slave rebellions in the Western Hemisphere, was in process. Ideas about enfranchisement, liberty, and equality were widespread. To Polwhele and others who shared his perspective, these ideas were perceived as attacks on religion, the monarchy, and the government. Women's advocacy of access to education[5] was confused with the most outrageous actions ascribed to the revolutionaries: free love, irreligion, and violent upheaval. Some commenters went so far as to blame the French Revolution on "a notorious dereliction of female principle" and "the dissipated and indelicate behaviour and loose morals" of French women.[6] Many of those who had initially supported the French Revolution turned away from the excesses of the Terror, and Britain was gripped by a strong backlash against any ideas that seemed in the least revolutionary. Janet Todd writes that "Britain, once priding itself on being the most politically enlightened and liberal state in Europe, came to define itself in increasingly conservative, patriotic, and anti-French terms."[7] "Gallic" and "French" came to mean, in the popular imagination, "revolutionary," so when Polwhele writes of "Gallic freaks" (l. 21) he is not merely describing fashions in clothing. Those Britons who sympathized with the French Revolution were known as "Jacobins." Those who opposed it were "Anti-Jacobins." The Antijacobin, or Weekly Examiner (1797–1798), the Anti-Jacobin Review, and the British Critic (1793–1843), were among the conservative journals that grew up during this highly polarized period. Polwhele, a conservative member of the Anglican clergy, was himself a contributor to the Anti-Jacobin Review. According to Eleanor Ty, although feminist thought had existed for decades, the women of the 1790s seemed "particularly threatening to the anti-Jacobins" because of "the outspoken claiming of their 'rights' shortly after and coinciding with the events in France that culminated in the Revolution."[8]

(See also A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.)

Publication history and reception

As indicated in the subtitle, "Addressed to the author of the Pursuits of Literature," Polwhele was inspired to write his poem after reading satirist Thomas Mathias' "blistering attack" on the democratisation of culture in his Pursuits of Literature (1798).[9] Mathias deplored "unsex'd female writers [who] now instruct, or confuse, us and themselves, in the labyrinth of politics, or turn us wild with Gallic frenzy."[10]

The Unsex'd Females was originally published anonymously in London in 1798 by Cadell and Davies in a standalone, one volume edition. The American edition of 1800 also included A Sketch of the Private and Public Character of P. Pindar, an attack on the anti-monarchical satiric poet John Wolcott (1738–1819), a pairing publisher William Cobbett apparently saw as "a marketable combination" for a presumably Tory readership.[11]

The Unsex'd Females was "well known" among the responses to Wollstonecraft and her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.[12] One reviewer comments this "ingenious poem" with its "playful sallies of sarcastic wit" against "our modern ladies,"[13] though others found it "a tedious, lifeless piece of writing."[14] Critical responses largely fell along clear-cut political lines. Mathias, whose Pursuits of Literature had been so inspirational to Polwhele, was himself somewhat tepid in his enthusiasm for the work.[15]

Structure and themes

The poem itself consists of 206 lines of heroic couplets. There are a quantity of footnotes, to the degree that they outweigh the poem, word for word, by a considerable margin. In these footnotes Polwhele elaborates on various points which might get lost in verse and underscores the primacy of his polemical purpose. In structure the poem is straightforward: Polwhele compares two groups of writers, the "unsex'd females" of the title — "unsex'd" meaning un-feminine or un-womanly — and a second group of exemplary women writers. He also makes some more general points about feminine decorum in the earlier part of the poem.

Unsex'd females

The poem betrays a particular animus for Mary Wollstonecraft and, by extension, others Polwhele considered to be of her radical, pro-French camp: writers Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Mary Robinson, Charlotte Turner Smith, Helen Maria Williams, Ann Yearsley, Mary Hays and Ann Jebb, and artists Angelica Kauffman and Emma Crewe. Strangely, perhaps, only Hays, Jebb and Smith shared political sympathies with Wollstonecraft, and Smith, by 1798, had turned her back on her previous ideas. The others, though, in different ways, all fell afoul of restrictive ideas of female (and class) decorum. Yearsley, for example, a labouring-class poet who had a dispute with her patron, Hannah More, is accused of longing "to rustle, like her sex, in silk" (l.102). According to one editor, "one can only conclude that Polwhele attacks these women not for what they are, but for what they are not: they are unsexed, unfeminine, either because they are immodest, or unsentimental, or insubordinate. Women must do more than simply avoid setting a bad example: they must provide a positive model of chaste, sentimental, subordinate femininity."[16] Of this transgressive group, Polwhele invites the reader:

Survey with me, what ne'er our fathers saw,

A female band despising NATURE's law,

As "proud defiance" flashes from their arms,

And vengeance smothers all their softer charms. (ll.11–14)

His remarks on Wollstonecraft, "whom no decorum checks" (l.63), stray from the literary and political into the personal; he invokes her complicated personal history and, of her death in childbirth, comments in a note: "I cannot but think, that the Hand of Providence is visible, in her life, her death… As she was given up to her 'heart's lusts,' and let 'to follow her own imaginations, that the fallacy of her doctrines and the effects of an irreligious conduct, might be manifested to the world; and as she died a death that strongly marked the distinction of the sexes, by pointing out the destiny of women, and the diseases to which they are liable" (29–30).

Proper ladies

After a catalogue of the various evils of the age, the poem ends on a positive note when it turns to a group of writers, many of them Bluestockings, who reverse the dangerous literary, philosophical and political trends outlined in the earlier sections. The approved writers, in contrast to the "witlings" (l.9) previously described, are lauded for their facility in combining morality and feminine decorum with literary publication, and comprise a number of Polwhele's acquaintance: Elizabeth Montagu is praised for her ability to "refine a letter'd age" (l.188) and Elizabeth Carter for hers to "with a milder air, diffuse / The moral precepts of the Grecian Muse" (ll.189–90). Frances Burney is praised for her ability to "mix with sparkling humour chaste / Delicious feelings and the purest taste" (ll.195–96). "And listening girls perceive a charm unknown / In grave advice, as utter'd by [Hester] CHAPONE" (ll.191–192). Anna Seward, Hester Thrale Piozzi, Ann Radcliffe, artist Diana Beauclerk, and, most centrally, Hannah More, who is set up as a sort of "anti-Wollstonecraft," complete the list of proper women writers:

… round their MORE the sisters sigh'd!

Soft on each tongue repentant murmurs died;

And sweetly scatter'd (as they glanc'd away)

Their conscious "blushes spoke a brighter day." (ll.203–206)

In The Unsex'd Females, Polwhele initially seems to divide women writers according to their sexual reputations, but a closer examination reveals that he positions them largely symbolically. Why, for example, would Emma Crewe be in Wollstonecraft's group while Diana Beauclerk is in More's, particularly as the two knew each other and worked together? Beauclerk, in fact, had her own scandalous history: divorced by her husband for adultery, revealed to have had a child by her lover while still married, she was hardly a "proper lady." She was, however, a well-connected, well-established member of the aristocracy who painted charming, decorative pieces. Hannah More herself, while hardly a revolutionary, held a number of ideas uncannily similar to those of Wollstonecraft, ideas about the importance of female education, for example.[17] Polwhele's polemical structure is not concerned with these nuances, however, and he positions these writers strictly according to his overarching scheme.

Botany

Polwhele had a variety of targets. In addition to literary and artistic improprieties, he deplored the popular female pastime of amateur botany. While this may seem a strange preoccupation to a contemporary reader, Polwhele was in fact intervening in an ongoing, and quite heated debate about the propriety of girls and women learning about the reproduction of plants, a debate that arose in part after Erasmus Darwin published an English translation of the work of Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, as well as his own poem, "The Loves of the Plants" (1790):

With secret sighs the Virgin Lily droops,

And jealous Cowslips hang their tawny cups.

How the young Rose in beauty's damask pride

Drinks the warm blushes of his bashful bride;

With honey'd lips enamour'd Woodbines meet,

Clasp with fond arms, and mix their kisses sweet. (ll.15–20)

To Polwhele this is practically pornography and he graphically depicts the repercussions should women and girls be allowed to practise botany:

With bliss botanic as their bosoms heave,

Still pluck forbidden fruit, with mother Eve,

For puberty in signing florets pant,

Or point the prostitution of a plant;

Dissect its organ of unhallow'd lust,

And fondly gaze the titillating dust. (ll.29–34)

Perhaps ironically, these lines in particular were singled out by the anti-Jacobin British Critic, apparently unaware of the authorship of the poem, as being in "bad taste."[18]

According to Ann B. Shteir, "Polwhele's objections [to women practicing botany] combine critiques of female scientific practices with critiques of other 'Gallic' and 'revolutionary' practices, such as acknowledging sexuality and teaching children about sex."[19] In a note, Polwhele writes that "Botany has lately become a fashionable amusement with the ladies. But how the study of the sexual system of plants can accord with female modesty, I am not able to comprehend… I have, several times, seen boys and girls botanizing together" (8). His concerns about propriety dovetail neatly with what Robin Jarvis describes as the "intellectual backlash provoked by the French Revolution" whereby "by the mid-1790s scientific opinions were no longer ideologically neutral."[20]

French fashions

Polwhele is concerned with the moral ramifications of the intellectual activities of girls and women, most centrally writing. He does not, however, restrain his comments to academic pursuits; he inveighs, for example, against French fashions in dress and draws a clear line from French style to French philosophy:

With equal ease, in body or in mind,

To Gallic freaks or Gallic faith resign'd,

The crane-like neck, as Fashion bids, lay bare,

Or frizzle, bold in front, their borrow'd hair;

Scarce by a gossamery film carest,

Sport, in full view, the meretricious breast. (ll.20–24)

There is a long-standing tradition of satirising the more extreme aspects of fashion, and women's fashion in particular. The less restrictive fashion of this period came in for considerable caricature. Polwhele, with his anti-French, nationalistic tone, contributes to a sub-set of such satires, a sub-set which expresses unease with feminism in terms of the "controversy concerning female fashions."[21]

Legacy

During his lifetime Polwhele was seen as a minor figure, though prolific, and after his death he was little read. The contemporary reader may find some of Polwhele's preoccupations, particularly botany and fashion, amusing. The Unsex'd Females, however, was a salvo in a propaganda war that the participants took extremely seriously. After the revolution in literary criticism in the 1970s and 1980s when it was successfully argued that works could not solely be judged on their literary merit, poems such as Polwhele's were resurrected. They have subsequently shed considerable light on the cultural moments during which they were written. The Unsex'd Females remains of considerable interest today as a vibrant example of the politically charged culture of the revolutionary period in Britain.

Notes

- ↑ Sharon M. Setzer, Introduction, A Letter to the Women of England and the Natural Daughter, Mary Robinson, Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2003

- ↑ Virginia Woolf, Ch. 4, A Room of One's Own, 1929.

- ↑ "John Dryden, Henry Vaughan, Sir William Temple, Wentworth Dillon, the earl of Roscommon, and Roger Boyle, the earl of Orrery, are among the many who wrote poems of tribute to Philips." Paula Loscocco, "Manly Sweetness: Katherine Philips among the Neoclassicals," Huntington Library Quarterly 56.3 (Summer 1993): n.2.

- ↑ William Godwin, Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798)

- ↑ See History of Feminism

- ↑ Jane West, Letters to a Young Lady, in which the Duties and Character of women are considered, 3 vols. (London, 1806), I 58.

- ↑ Janet Todd, The Sign of Angelica: women, writing and fiction, 1600–1800 (London: Virgo, 1989. 196.) See also John Bull.

- ↑ Eleanor Rose Ty, Unsex'd Revolutionaries: Five Women Novelists of the 1790s (University of Toronto Press, 1993. 4).

- ↑ Thomas James Mathias, The Pursuits of Literature: A Satirical Poem in Four Dialogues. 6th. ed. London: T. Becket, 1798.

- ↑ "Judith Pascoe, "'Unsex'd females': Barbauld, Robinson, and Smith," The Cambridge Companion to English Literature, 1740–1830, Jon Mee and Tom Keymer, eds. (Cambridge University Press, 2004. 212).

- ↑ Noah Heringman, " 'Manlius to Peter Pindar': Satire, Patriotism, and Masculinity in the 1790s," Romantic Circles Praxis Series: Romanticism and Patriotism: Nation, Empire, Bodies, Rhetoric, May 2006.

- ↑ Adriana Craciun, Mary Wollstonecraft's a Vindication of the Rights of Woman: A Sourcebook (Routledge, 2002, 2).

- ↑ Ralph Griffiths, The Monthly Review 30 (1799): 103.

- ↑ Introduction, The Unsex'd Females, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- ↑ Appendix I, The Unsex'd Females, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- ↑ Introduction, The Unsex'd Females, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library. See also William Stafford, English Feminists and Their Opponents in the 1790s: unsex'd and proper females (Manchester University Press, 2002) for the argument that Polwhele and other Anti-Jacobin critics were inconsistent, approving the public speech of their female allies while deploring the same activities in their opponents.

- ↑ Literary scholar Mitzi Myer has argued that the political binaries of "conservative" and "progressive," "left" and "right," do not always apply in the 18th century. Mitzi Myers, "Reform or Ruin: 'A Revolution in Female Manners,'" Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 11 (1982): 199–216.

- ↑ William Stafford, English Feminists and Their Opponents in the 1790s: unsex'd and proper females (Manchester University Press, 2002. 2).

- ↑ Ann B. Shteir, Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora's Daughters and Botany in England, 1760 to 1860 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. 28.)

- ↑ Robin Jarvis, The Romantic Period: the intellectual and cultural context of English literature, 1789–1830 (Harlow, UK: Pearson/Longman, 2004. 120.)

- ↑ Paul Langford, A Polite and Commercial People: England 1727–1783, Oxford University Press, 1994, 603.

Bibliography

- Calè, Luisa. "'A Female Band despising Nature's Law': Botany, Gender and Revolution in the 1790s." Romanticism on the Net 17 (February 2000). Accessed 24 April 2007.

- Courtney, W. P. ‘Polwhele, Richard (1760–1838)’, rev. Grant P. Cerny. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed 19 Feb 2007.

- Haut, Asia. "Reading Flora: Erasmus Darwin's The Botanic Garden, Henry Fuseli's illustrations, and various literary responses." Word & Image 20.4 (Oct–Dec 2004):240–256.

- Lovell, Jennifer. "A Bath Butterfly Botany and Eighteenth Century Sexual Politics." National Library of Australia News 15.7 (April 2005).

- Pascoe, Judith. "'Unsex'd females': Barbauld, Robinson, and Smith." The Cambridge Companion to English Literature, 1740–1830. Jon Mee and Tom Keymer, eds. Cambridge University Press, 2004. 211–226.

- Polwhele, Richard (1810). Poems. London: Rivington's. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Rizzo, Betty. "Male Oratory and Female Prate: 'Then Hush and Be an Angel Quite'." Eighteenth-Century Life 29.1 (2005) 23–49.

- Shteir, Ann B. Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora's Daughters and Botany in England, 1760 to 1860. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8018-6175-6 ISBN 0-8018-5141-6.

- Stafford, William (2002). English Feminists and Their Opponents in the 1790s: Unsex'd and Proper Females. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719060823. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Todd, Janet. "The Polwhelean Tradition and Richard Cobb." Studies in Burke and His Time 16 (1975):271–77.

- Ty, Eleanor Rose. Unsex'd Revolutionaries: Five Women Novelists of the 1790s. University of Toronto Press. 1993.

- Byrnes, Peter: The unsex'd females: a poem, addressed to the author of the Pursuits of literature University of Oxford Text Archive

External links

- Erasmus Darwin, "The Botanic Garden. Part II. Containing the Loves of the Plants. a Poem. With Philosophical Notes." (Etext, Project Gutenberg)

- Richard Polwhele, The Unsex'd Females: A Poem, Addressed to the Author of the Pursuits of Literature. London: Printed for Cadell and Davies, in the Strand. 1798. (Etext, U of Virginia)

- Preposterous Headdresses and Feathered Ladies: Hair, Wigs, Barbers, and Hairdressers. An Exhibit at the Lewis Walpole Library, May 8-October 29, 2003.

- Anna Seward, "Sonnet to the Rev. Richard Polwhele" (written before 1799; reprinted 1810)

.jpg)