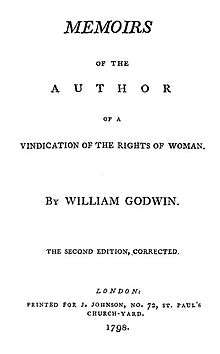

Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798) is William Godwin's biography of his wife Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).

Godwin felt it was his duty to edit and publish Wollstonecraft's unfinished works after her death. A week after her funeral, he started on this project and a memoir of her life. In order to prepare to write the biography, he reread all of her works, spoke with her friends, and ordered and numbered their correspondence. After four months of hard work, he had completed both projects. According to William St Clair, who has written a biography of the Godwins and the Shelleys, Wollstonecraft was so famous by this time that Godwin did not have to mention her name in the title of the memoir.[1]

Published in January 1798, Godwin's account of Wollstonecraft's life is wracked with sorrow and, inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Confessions, unusually frank for its time.[2] He did not shrink from presenting the parts of Wollstonecraft's life that late eighteenth-century British society would judge either immoral or in bad taste, such as her close friendship with a woman, her love affairs, her illegitimate child, her suicide attempts and her agonizing death.[3][4] In the "Preface", Godwin explains:

I cannot easily prevail on myself to doubt, that the more fully we are presented with the picture and story of such persons as the subject of the following narrative, the more generally shall we feel in ourselves an attachment to their fate and a sympathy in their excellencies. There are not many individuals with whose character the public welfare and improvement are more intimately connected than the author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman.[4]

Godwin's openness was not always appreciated by the people he named or by Wollstonecraft's sisters. Everina and Eliza ran a school in Ireland and they lost students as a result of the Memoir.[5]

Joseph Johnson, Wollstonecraft's life-long friend and the book's publisher, tried to dissuade Godwin from including explicit details regarding her life, but he refused.[6] However, the book was heavily criticized and Godwin was forced to revise it for a second edition in August of the same year.[7] Rarely published in the nineteenth century and sparingly even today, Memoirs is most often viewed as a source for information on Wollstonecraft. However, with the rise of interest in biography and autobiography as important genres in and of themselves, scholars are increasingly studying it for its own sake.[8][9]

Claudia Johnson has written that "Godwin's Memoirs appeared virtually to celebrate Wollstonecraft's suicidal tendencies as somehow appropriate in a heroine of her exquisite sensibility".[10]

The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine pilloried the book, writing that "if it does not shew what it is wise to pursue, it manifests what it is wise to avoid. It illustrates both the sentiments and conduct resulting from such principles as those of Mrs. Wollstonecroft [sic] and Mr. Godwin. It also in some degree accounts for the formation of such visionary theories and pernicious doctrines."[11] The review surveys Wollstonecraft's entire life and indicts almost every element of it, from her efforts to care for Fanny Blood, her close friend, to her writings. Of her two Vindications in particular, it criticizes her "extravagance" and lack of logic.[12] However, when the review comes to discuss her relationship with Gilbert Imlay, it tips over into outright slander, accusing her of being a "concubine" and a "kept mistress" and writing "the biographer does not mention many of her amours. Indeed it was unnecessary: two or three instances of action often decide a character as well as a thousand."[13] Rising to a fever pitch at the end, the review claims that "the moral sentiments and moral conduct of Mrs. Wollstonecroft [sic], resulting from their principles and theories, exemplify and illustrate JACOBIN MORALITY" and warns parents against bringing up their children using her advice.[7][14]

Notes

- ↑ St Clair, 180.

- ↑ St Clair, 184.

- ↑ Clemit and Walker, "Introduction"

- 1 2 St Clair, 182.

- ↑ St Clair, 182, 184.

- ↑ St Clair, 183.

- 1 2 St Clair, 185.

- ↑ Clemit and Walker, "Introduction".

- ↑ St Clair, 183–84.

- ↑ Johnson, Claudia. Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1988), 64.

- ↑ Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine (July 1798), 94.

- ↑ Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine (July 1798), 95.

- ↑ Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine (July 1798), 97.

- ↑ Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine (July 1798), 98–9.

Bibliography

- —. Analytical Review 27 (March 1798): 235-240.

- —. Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine 1 (July 1798): 94-102.

- —. Lady's Monitor 1 (12-17 (November–12 December 1801): 91-131.

- —. Monthly Review 27 (November 1798): 321-324.

- —. New Annual Register for 1798 (1799): 271.

- Favret, Mary. Romantic Correspondence: Women, Politics and the Fiction of Letters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Godwin, William. Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Eds. Pamela Clemit and Gina Luria Walker. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2001. ISBN 1-55111-259-0.

- Jones, Vivien. "The Death of Mary Wollstonecraft". British Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 20.2 (1997): 187-205.

- Myers, Mitzi. "Godwin's Memoirs of Wollstonecraft: The Shaping of Self and Subject". Studies in Romanticism 20 (1981): 299-316.

- St Clair, William. The Godwins and the Shelleys: The biography of a family. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1989. ISBN 0-8018-4233-6.

- Todd, Janet. "Mary Wollstonecraft and the Rights of Death". Gender, Art and Death. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993.

- Tomalin, Claire. The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft. Rev. ed. New York: Penguin, 1992. ISBN 0-14-016761-7.

.jpg)