Tamil Muslim

| தமிழ் முஸ்லிம்கள் | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| (6 – 7 million) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 3.5 – 4 million | |

| 2,000,000 | |

| 500,000 | |

| 20,000 as of 1992[1] | |

| Rest of the World | 1 million |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Indian Muslims, Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka, Dravidian people, Sri Lankan Moors, Jawi Peranakan, Kilakarai Moors, Lebbai, Marakayar, Rowther, Kayalar | |

Tamil Muslims (Tamil: தமிழ் முஸ்லிம்கள், tamiḻ muslimgal ?) are Tamil-speaking people with Islam as their faith. There are 3 – 4 million Tamil Muslims in India mostly in Tamil Nadu state and also in neighbouring Kerala and Karnataka. A significant Tamil-speaking Muslim population numbering 1.8 million[2] or more live in the Northern and Eastern provinces and Colombo in Sri Lanka and many other pockets across central and southwest provinces, however they are listed as a separate ethnic group in official statistics.[3] There are around 500,000 in Malaysia and 20,000 in Singapore.[4] Tamil Muslims are largely urban traders rather than farmers. There is a substantial diaspora of Tamil Muslims, particularly in South East Asia, which has seen their presence as early as the 13th century.[5] In the late 20th century, the diaspora expanded to North America and Western Europe. They are called Cholias in Myanmar, Mamak in Malaysia and Rathas in South Africa.[6]

Ethnic identity

Tamil Muslims are identifiable and bonded only by a common language and faith. Otherwise, they belong to multiple ethnicities such as Dravidian, Aryan, Oriental and Semitic. Hence, their complexions range from fair to dark, facial bone structures range from sharp/oval to rounded. This was due to the frequent trading and miscegenation in South and East Asia. These races, by the 20th century, began to be listed as social classes in official gazettes of different nations as Lebbai, Marakayar, Rowther, Dekkani, Kayalar (in Maharashtra), Jawi Peranakan in Malaysia,[7][8][9][10] and Chulia[11] (in Singapore)

Law and politics

P. Kalifullah (1888–1961), was a politician of the Madras Presidency, British India. He served as the minister for public works in the Cabinet of Kurma Venkata Reddy Naidu during April–July 1937. His father T.A. Pitchai Rowther was an affluent entrepreneur from Tiruchirapalli. He belonged to the All-India Muslim League and was elected to the Madras Legislative Assembly from Tiruchirappalli in the 1937 elections. He was sympathetic to the cause of Periyar E. V. Ramasamy (Periyar) and his Self-Respect Movement. In 1937, he spoke against the introduction of compulsory Hindi classes in the Madras legislature and later participated in the anti-Hindi agitation started by Periyar. He was a lawyer by profession and was known by his honorifics as Khan Bahadur. He was also a member of the Madras Legislative Council during the early 1930s. He was the Dewan of Pudukottai after his withdrawal from political work.

In the early 19th century, Munshi Abdullah's essays on good governance and education reforms began to shape the modern Malaysian political system.

Sir Mohammad Usman was the most prominent among the early political leaders of the community. In 1930, Jamal Mohammad became the president of the Madras Presidency Muslim League.[12] Until then, the party was dominated by Urdu-speakers from the Nizamat of Hyderabad. Yakub Hasan Sait served as a minister in the Rajaji administration. Allama Karim Gani, veteran freedom fighter and a close associate of Subash Chandra Bose, who hailed from Ilayangudi, served as Information Minister in Netaji BAMA Ministry during the 1930s.

Since the late 20th century, politicians like Quaid E Millath (a close friend of Annadurai, former MP and leader Tamil Nadu Muslim League) and Dawood Shah advocated Tamil to be made an official language of India due to its antiquity in parliamentary debates[13] New leaders like Daud Sharifa Khanum have been active in pioneering social reforms like independent mosques for women.[14][15][16][17] MM Ismail was appointed additional judge of the Delhi High Court in 1967 and was transferred to the Madras High Court later. He became Chief Justice in 1979. On October 27, 1980 Justice MM Ismail was sworn in as acting Governor of Tamil Nadu. As Kamban Kazhagam president, he was responsible for organising literary festivals, which focussed on classical Tamil literature. Another prominent legal luminary is Justice SA Kader who was the Judge of Madras High Court from 1983 to 1989. He was held in high esteem for his quick grasp and speedy disposal of cases. On retirement, he held the office of President of the Tamil Nadu State Government Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission. At present, he is a Senior Advocate of the Supreme Court.[18]

MLAs and MPs such as JM Haroon, Abdul Rahman, Jinna, Sheik Umar (Tut), Khaleelur Rahman, Ubayadullah, Hassan Ali and T. P. M. Mohideen Khan are found across all major Dravidian political parties like Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, as well as national parties like the Indian National Congress. Former Prime Minister of Malaysia Dr.Mahathir as well as Kadir Sheikh Fadzir, Zainuddin Maidin, Anwar Ibrahim, Khairy Jamaluddin, Nor Mohamed Yakcop and Zambry Abdul Kadir too are of Tamil origins. Broadly speaking, Tamil Muslims tend to support laissez faire and free trade; and have thus been unimpressed by Communism as a public policy though fringe working class groups often called for affirmative action in the last quarter of the 20th century.[19]

Quaid-e-Millath Muhammad Ismail Sahib, became the first President of Indian Union Muslim League, soon after independence of India. The community was united in a single political party under his statesmanship. Their support was inevitable for ruling parties in the state, as well as in the Centre. He was instrumental in framing and obtaining the minority status and privileges for minorities in India. His newspaper Urimaikkural was a very popular daily.

SM Muhammed Sheriff, a.k.a. 'Madurai Sheriff Sahib' was a charismatic and prominent leader groomed by Quaid-e-Millath Sahib. He was the first elected Muslim League MP from Tamil Nadu. He produced clear documentary evidences that Kachchatheevu belonged to India. During Emergency in Indira Gandhi's period, he was the advisor to the Governor on the legislation of Tamil Nadu. He was a close associate of Sayyid Abdur Rahman Bafaqi Thangal, C. H. Mohammed Koya, Panakkad Shihab Thangal, Ebrahim Sulaiman Sait, GM Banatwalla, AK Rifayee and Siraj-ul-Millath Abdul Sammad, and the bosom friend of Nagore E.M. Hanifa, Justice Basheer Ahmed Sayeed and B. S. Abdur Rahman. He was a powerful speaker in many Indian languages. As propaganda secretary of the IUML, he strengthened, expanded and ignited the spirit of the league from grass-root level.

In Tamil Nadu and other Indian states, IUML led by Quaid-e-Millath Sahib was famous till the early 1990s. After the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, a feeling of insecurity gripped the community. Tamil Muslim youths swayed from general apathy, sought change to more involvement and interest in parochial politics. The elderly preferred the status quo and continued to national politics. Subsequently, the Indian National League split from the IUML.

In Jan, 2011, the Tamil Nadu State Unit of Indian Nation League was dissolved.[20] The Ahle-Hadith (Ghair Muqallid) reform movements began to take the front stage spearheaded by P. Jainulabdeen and consequently the organization, Tamil Nadu Muslim Munnetra Kazagham was constituted in 1995. This non-profit organisation quickly became popular and assertive among the working class. Manithaneya Makkal Katchi, the political arm of TMMK, Tamil Nadu Thowheed Jamath, the non-political arm was formed. MMK contested in three seats and won two Assembly seats viz. Ambur (A. Aslam Basha) and Ramanathapuram (M.H. Jawahirullah).

In 2016 Assembly elections, Aloor Shanavas, Deputy General Secratery of Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi contested from Kunnam constituency and lost to AIADMK candidate.[21]In recent past he bacame the prominent youth face in Tamilnadu politics.[22]

Culture

There are two main holidays in Islam: Eid Al-Fitr, Ramadan and Eid Al-Adha. Eid Al-Fitr is celebrated at the end of Ramadan (a month of fasting), and Muslims usually give zakat (charity) on the occasion. Eid Al-Adha is celebrated at the end of Hajj (annual pilgrimage to Mecca), which is one of the five pillars, and Muslims usually sacrifice an animal and distribute its meat among family, friends and the poor. All Islamic holidays follow the lunar calendar, and thus move each year relative to the solar calendar. The Islamic calendar has 12 months and 354 days on a regular year, and 355 days on a leap year.

Economy

The global purchasing power of Tamil Muslims in 2015 was estimated at almost $23 billion viz. $8 billion in Sri Lanka, $6 billion in Tamil Nadu, $5 billion in Malaysia, $1 billion in Singapore and $3 billion from rest of the world. Tamil Muslims have historically been money changers[23] (not money lenders) throughout South and South East Asia especially in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Hong Kong are dominated by them.[24]

Tamil Muslims are also involved in various trades like retail, mutton shops, foreign bazaars, etc.[25] They are also involved in pearl/gem trade[26] and leather industry.[27] The coloured stone business which Sri Lanka is famous for is in the hands of Tamil Muslims. Other than Gujarati and Marwaris, the only community doing wholesale diamond business in ASEAN is Tamil Muslim from Ramanathapuram district. Semiprecious stones like peridot, rubilite, amethyst, or moonstone are led by Tamil Muslims from Thanjavur district in ASEAN. Paper business is run by entrepreneurs from Erwadi. Department store and textile showrooms are run by businessmen from Pallapatti. The largest exporters of leather products are from Ambur, Vaniyambadi, Pernambettu, Ranipet and Melvisharam. Independent shops in Burma Bazaar market of Chennai is led by entrepreneurs from Ramanathapuram district. Due to new emerging opportunities, lot of Tamil Muslims went to the Persian Gulf and ASEAN.[28]

There are about 2,000 HNWI entrepreneurs within the community and at least one billionaire viz. B.S. Abdur Rahman (better known as the Buhari Group) who founded the conglomerate ETA Star Group, Chennai Citi Centre, Chepauk Stadium, Marina Lighthouse, Valluvar Kottam, Government General Hospital, Gemini Flyover, Crescent Engineering College, et al.. He owned over 70 ocean-going vessels.[29] Periya Thambi Nainar of the 17th century was widely regarded as the first millionaire from the Tamil Muslim community.[30][31]

Education

After independence, Tamil Muslim entrepreneurs began to build schools and colleges. Jamal Mohamed College in Trichy, Waqf Board College in Madurai, Khadir Mohideen College, Adirampattinam, New College in Chennai and Haji Karutha Rowther Hawdhiya College in Uthamapalayam are some of famous service based Tamil Muslim colleges. In the mid 1980s, scores of Tamil Muslim self-financing educational institutions were started. Crescent Engineering College was upgraded to BS Abdur Rahman University. In Tamil Nadu, the school education of the Tamil Muslims is above-average compared to general literacy level. But in higher and technical education Tamil Muslims lag behind, due to entrepreneurial commitments and jobs in the Persian Gulf and South East Asia. But now the picture is changing slowly. There are over 65 Tamil Muslim educational institutions in Tamil Nadu.

Legends and rituals

The Aqidah of the Tamil Muslims is based on Sunnah heavily influenced by the Shadhili and Qadiri flavours of Sufism. While Marakkayars adhere to Shafi school, Rowthers favour Hanafi madhab. Coastal families tend to be matrilocal, matrilineal and matriarchal as male members work overseas for long terms. The nikkah (marriage) registers mahr (dower) and witness. For instance, it is common to see a groom pay the bride mahr (dower) of ₹10,000. Tamil Muslims practice monogamy and male circumcision.[32] Like the thali of Tamil Hindu brides, Tamil Muslim women wear a chain strung with black beads called Karugamani which is tied by the groom's elder female relative to the bride's neck on the day of nikkah.[33] As a mark of modesty Tamil Muslim women usually wear white thuppatti (whilst travelling only) which is draped over their whole body on top of the saree. Many Tamil Muslims visit (Dargah) ziyarat on major life milestones like child births.[34]

Literature

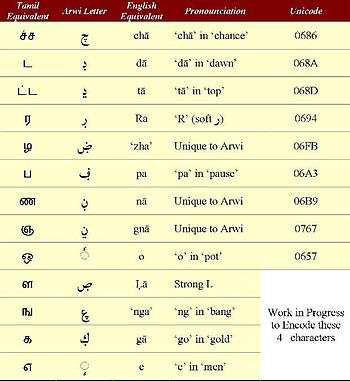

Tamil Muslim culture and literature are heavily influenced by the Shadhili and Qadiri flavours of Sufism. Their domain range from mystical to medical, from fictional to political, from philosophical to legal. Few Tamil Muslims wrote Tamil literature in Nastaliq script, known as Arwi.[35] The Arwi language is a written register of the Tamil language with some alphabets and usages borrowed from the Arabic language. It is the widely used dialect among Tamil Muslims of Sri Lanka.[36] A few Islamic schools still teach the basics of Arwi as part of their curricula. The earliest Tamil Muslim literary works could be traced to the 14th century in the form of Palsanthmalai, a small work of eight stanzas. In 1572, Seyku Issaku, better known as Vanna Parimala Pulavar, published Aayira Masala Venru Vazhankum Adisaya Puranam detailing the Islamic principles and beliefs in a FAQ format. In 1592, Aali Pulavar wrote the Mikurasu Malai. The epic Seerapuranam by Umaru Pulavar is dated to the 17th century[37] and still considered as the crowning achievement of Tamil Muslim literature. Other significant works of 17th century include Thiruneri Neetham by Sufi master Pir Mohammad, Kanakabhisheka Malai by Seyku Nainar Khan (alias Kanakavirayar), Tirumana Katchi by Sekathi Nainan and the Iraq war ballad Sackoon Pataippor.[38] Notable publications of 18th century include Yakobu Sithat Patal, a medical primer on Siddha Vaithyam (distinguished from Ayurvedic medicine).[39] Nevertheless, an independent Tamil Muslim identity evolved only in the last quarter of the 20th century triggered by the rise of Dravidian politics as well as the introduction of new mass communications and lithographic technologies.[40][41] The world's first Tamil Islamic Literature Conference was held in Trichy in 1973. In early 2000. the Department of Tamil Islamic Literature was set up in the University of Madras.[42] Literati such as Kavikko Abdur Rahman, Mu Metha, Jainulabudeen, Pavalar Inqulab, A. Rokkiah[43] and A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, the 11th President of India, helped push the frontiers of enlightenment into the 21st century.[44] The pioneering fortnightly journal Samarasam was established in 1981 to highlight and cater to the ethnic Tamil Muslim community's issues. Aayiram Masala (Questions) was dated to be 450–500 years old, other than the popularly known Seera Puranam written by Umaru pulavar. In the modern times, Tamil poetry was enriched by contributions from Kavikko Abdur Rahman, Kavi Kaa Mu Sheriff, Kavignar Mu Metha, Bismi, Manavai Musthafa, Salma, APJ Abdul Kalam etc.[45] Established in 1979, Islamic Foundation Trust has published 129 books in Tamil, 14 in English and 16 in Arabic languages. It has also brought out audio Cassettes and CDs of the Noble Quran.[46]

Vocabulary

Tamil Muslim vocabulary includes several peculiar Malay[47] loanwords like thuppatti (purdah), nabi (messenger of god),[48] thozhugai (prayer), nonbu (fasting), kayili (lungi), chicha (younger paternal uncle), peribaapu (elder paternal uncle), peribuvva (wife of elder paternal uncle), chichani (wife of younger paternal uncle), pallivaasal (mosque), aanam (curry), et al. The vocabulary varies across sects. Western and Northern districts of Tamil Nadu use different words influenced by Malayalam and Arabic.[49] The word Marakkayar comes from the Arabic markab meaning a boat.[50]

Art

Artistes such as Nagore S.M.A.Kadir,(Carnatic Musician), Sheik Chinna Moulana, (Nadawaram Vidwan), Nagore E.M. Hanifa, Kaayal A.R. Sheik Mohamed, Nassar (actor), Shaam (actor), Ameer Sultan, Rajkiran (Tamil Actor), B. H. Abdul Hameed, Shahul Hameed, A. R. Rahman,Pakoda Kader are popular in the Tamil film industry.

Cuisine

Tamil Muslim cuisine is a syncretic mixture of Tamil Hindu and Northern Muslim recipes and flavours.[51] Its distinguishing feature is the total absence of hot kebab and pungent colorful spices that tend to permeate most Indian non-vegetarian food. The spice used is basically the same as those used by other South Indian communities, though the mixtures might vary. One special dish is 'kuruma' which is very low on chilly where the hotness is substituted by increasing the amount of white pepper, and with a heavy dose of poppy seed paste. This dish is further made richer by adding ground almonds and cashew nuts. Pandanus amaryllifolius Pandan leaves are used where it's available, especially in Sri Lanka and the Malay archipelago. This leaf gives out a distinct flavour only when cooked. In deltaic towns like Karaikal and Ambagarathur, sahan saappaadu is the main style of food presentation in banquets (where two or more guests eat from one large round plate, while seated on the floor). Tamil Muslim cuisine also includes the use of masi or cured/dried tuna fish, which is powdered and used with many different items. But this is limited to the coastal districts. They also use ada urugai, which is whole lime pickled in salt without chillies; this is mashed and mixed with the masi powder. The combination gives a sour taste and a distinctly different flavor. The diet of Tamil Muslims is non-vegetarian and seldom includes beef. Coconut oil is used for dressing while a few older generation folks chew betel tobacco after a heavy lunch.[52]

References

- ↑ Mani, A. (1992). "Aspects of identity and change among Tamil Muslims in Singapore Aspects of identity and change among Tamil Muslims in Singapore". Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs, Journal. 13 (2): 337–357. doi:10.1080/02666959208716253.

- ↑ Mattison Mines, Social stratification among the Muslims in Tamil Nadu, South India, Caste and Social Stratification Among Muslims in India, ed. Imtiaz Ahamed, New Delhi, 1978; Muslim Merchants – The Economic Behaviours of the Indian Muslim Community, Shri Ram Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources, New Delhi, 1972

- ↑ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, pp. 3–5, 9

- ↑ Sinnappa Arasaratnam, Merchants, Companies and Commerce on the Coromandel Coast 1650 – 1740, New Delhi 1986; Maritime India in the Seventeenth Century, New Delhi 1994; Maritime Commerce and English Power (South East India), 1750 – 1800, New Delhi 1996; Dutch East Indian Company and the Kingdom of Madura, 1650 – 1700, Tamil Culture, Vol. 1, 1963, pp. 48–74; A Note on Periyathambi Marakkayar, 17th century Commercial Magnate, Tamil Culture, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1964, pp. 1–7; Indian Merchants and the Decline of Indian Mercantile Activity, the Coromandel case, The Calcutta Historical Journal, Vol. VII, No. 2/1983, pp. 27–43; Commerce, Merchants and Entrepreneurship in Tamil Country in 18th century, paper presented in the 8th World Tamil Conference seminar, Thanjavur, 1995

- ↑ Tamil Muslims in Zheng He's fleet. 1421.tv. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ A. R. Sayeed, Indian Muslims and some Problems of Modernisation, Dimensions of Social Changes in India, ed. M. N. Srinivas, New Delhi, 1977, p.217

- ↑ Tamil Muslims dominate restaurant industry in Malaysia

- ↑ Kings, Sects and Temples in South India. Ier.sagepub.com (1977-01-01). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ Understanding Backward Classes of Muslim Society. Scribd.com (2010-08-21). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ Hiltebeitel, A (1999) Rethinking India's oral and classical epics. p. 376 (11). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-34050-3

- ↑ Zafar Anjum, Indians Roar In The Lion City. littleindia.com

- ↑ J.B.P.More (1 January 1997). Political Evolution of Muslims in Tamilnadu and Madras 1930–1947. Orient Blackswan. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-81-250-1192-7. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ Tamil Muslim Periyar Thatstamil.oneindia.in. Retrieved on 2012-06-27

- ↑ Biswas, Soutik. (2004-01-27) World's first Masjid for Women. BBC News. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ Pandey, Geeta. (2005-08-19) World | South Asia | Women battle on with mosque plan. BBC News. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ S.T.E.P.S.

- ↑ TMMK opposes a mosque!. News.newamericamedia.org. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ http://www.supremecourtofindia.nic.in/circular/senioradvocates.pdf

- ↑ Susan Bayly, Saints, Goddesses and Kings — Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, Cambridge, 1989

- ↑ Tamil Nadu / Chennai News : Indian National League State unit dissolved. The Hindu (2011-01-21). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ "Kunnam constituency candidates list".

- ↑ "Aloor shanavaz at age 30".

- ↑ N. Seeralan, The Survey of Ports and Harbours in Madras Presidency 1858 – 1900, unpublished M.Phil. thesis, Bharatidasan University, Tiruchirapalli, 1987, p. 31

- ↑ Historical dominance on money changing business. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ C. W. E. Cotton, Handbook of Commercial Information for India, Trivandrum, 1942, p. 67

- ↑ S. Arunachalam, The History of Pearl Fishery of Tamil Coast, Annamalai Nagar 1952, p. 11

- ↑ Sanjay Subramanian, The Political Economy of Commerce, Southern India 1500 – 1650, New York 1990

- ↑ T. Jayarajan, Social and Economic Customs and Practices of Marakkayars of Tamil Nadu — a case study of Marakkayars of Adiramapattinam, unpublished M.Phil. thesis, Bharatidasan University, Tiruchirapalli, 1990

- ↑ Buhari Group's global reach

- ↑ Burten Stein, All the Kings' Manas and Papers on Medieval South Indian History, Madras 1984, p. 243

- ↑ R. E. M. Wheeler and A. Ghosh Arikkamedu — an Indo-Roman Trading Centre on the East Coast of India, Ancient India, No.2, New Delhi 1956, pp. 17–124

- ↑ Robert Caldwell, A Political and General History of the District of Tirunelveli in the Presidency of Madras, from the earliest period to its cession to the English Government in 1801 (Rpt) New Delhi, 1989, pp. 282–288

- ↑ Syed Abdul Razack, Social and Cultural Life of the Carnatic Nawabs and Nobles — as gleaned through the Persian sources, unpublished M.Phil. thesis, University of Madras, 1980

- ↑ Stephen F' Dale Recent Researches on the Islamic Communities of Peninsular India, Studies in South India, ed. Robert E. Frykenbers and Paulin Kolenda (Madras 1985)

- ↑ Islam in Tamilnadu: Varia. (PDF) Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ 216 th year commemoration today: Remembering His Holiness Bukhary Thangal Sunday Observer – January 5, 2003. Online version accessed on 2009-08-14

- ↑ The Diversity in Indian Islam. International.ucla.edu. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India, London 1886, VIII p. 216; N. A. Ameer Ali, Vallal Seethakkathiyin Vaazhvum Kaalamum, Madras 1983, p. 30-31, Ka. Mu. Sheriff, Vallal Seethakkathi Varalaru, 1986, pp. 60–62, M. Idris Marakkayar, Nanilam Potrum Nannagar Keelakkarai, 1990

- ↑ Durate Barbosa, The Book of Durate Barbosa: An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and their Inhabitants, ed. M. L. Dames, London Hakluyt Society, 1980, II, p. 124

- ↑ Tamil Muslim identity. Hindu.com (2004-10-12). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ J.B.P.More (1 January 2004). Muslim Identity, Print Culture, and the Dravidian Factor in Tamil Nadu. Orient Blackswan. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-81-250-2632-7. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ Islamic Voice (magazine)

- ↑ Irandaam Jaamangalin Kathai. Hindu.com. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ Rebel Poet in the Panchayat. Boloji.com (2004-06-26). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ Islamic Foundation Trust(IFT). Ift-chennai.org. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ Samarasam tamil Magazine. Samarasam.net. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ↑ J. H. Garstin, Manual of South Arcot District, Madras 1878, p. 408

- ↑ A Manual of Madras Presidency (ed) C. D. Macleans, Madras 1885, II, p. 423

- ↑ S. M. H. Nainar (Tr) Tuhfat-ul-Mujahidin of Zainuddin, University of Madras, 1942, p. 6; Arab Geographers' knowledge of South India, University of Madras, 1942, pp. 53–56

- ↑ Marakkayar is derived from Markab (boat)

- ↑ Business Line Archived July 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kumar Suresh Singh (2004). People of India: Maharashtra. Popular Prakashan. pp. 1930–. ISBN 978-81-7991-102-0. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

External links

- TNTJ to support DMK in 2011 elections if Muslims Quota increased. Twocircles.net. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- Thousands of Muslims converge at massive TNTJ rally. IndianMuslimobserver.com (2011-01-28). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- web Rating for TNTJ. Alexa (2010-02-16). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- TNTJ demands 10 percentage reservation for muslims. The Hindu (2010-06-13). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.