Tōdai-ji

| Tōdai-ji 東大寺 | |

|---|---|

|

Great Buddha Hall (daibutsuden), a National Treasure | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | 1 Zōshi-chō, Nara, Nara Prefecture |

| Affiliation | Kegon |

| Deity | Birushana-butsu (Vairocana Buddha) |

| Country | Japan |

| Website | http://www.todaiji.or.jp/ |

| Architectural description | |

| Founder | Emperor Shōmu |

| Completed | Early 8th century |

Tōdai-ji (東大寺, Eastern Great Temple)[1] is a Buddhist temple complex, that was once one of the powerful Seven Great Temples, located in the city of Nara, Japan. Its Great Buddha Hall (大仏殿 Daibutsuden), houses the world's largest bronze statue of the Buddha[2] Vairocana,[3] known in Japanese simply as Daibutsu (大仏?) . The temple also serves as the Japanese headquarters of the Kegon school of Buddhism. The temple is a listed UNESCO World Heritage Site as one of the "Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara", together with seven other sites including temples, shrines and places in the city of Nara. Deer, regarded as messengers of the gods in the Shinto religion, roam the grounds freely.

History

Roots

The beginning of building a temple where the Tōdai-ji complex sits today can be dated to 728, when Emperor Shōmu established Kinshōsen-ji (金鐘山寺) as an appeasement for Prince Motoi (ja:基王), his first son with his Fujiwara clan consort Kōmyōshi. Prince Motoi died a year after his birth.

During the Tenpyō era, Japan suffered from a series of disasters and epidemics. It was after experiencing these problems that Emperor Shōmu issued an edict in 741 to promote the construction of provincial temples throughout the nation. Tōdai-ji (still Kinshōsen-ji at the time) was appointed as the Provincial temple of Yamato Province and the head of all the provincial temples. With the alleged coup d'état by Nagaya in 729, an outbreak of smallpox around 735–737, worsened by consecutive years of poor crops, then followed by a rebellion led by Fujiwara no Hirotsugu in 740, the country was in a chaotic position. Emperor Shōmu had been forced to move the capital four times, indicating the level of instability during this period.[6]

Role in early Japanese Buddhism

According to legend, the monk Gyoki went to Ise Grand Shrine to reconcile Shinto with Buddhism, spending seven days and nights reciting sutras until the oracle declared Vairocana Buddha compatible with worship of the sun goddess Amaterasu.[7]

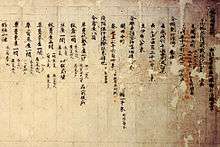

Under the Ritsuryō system of government in the Nara Period, Buddhism was heavily regulated by the state through the Sōgō (僧綱, Office of Priestly Affairs). During this time, Tōdai-ji served as the central administrative temple for the provincial temples[8] for the six Buddhist schools in Japan at the time: the Hossō, Kegon, Jōjitsu, Sanron, Ritsu and Kusha. Letters dating from this time also show that all six Buddhist schools had offices at Tōdai-ji, complete with administrators, shrines and their own library.[8]

Japanese Buddhism during this time still maintained the lineage of the Vinaya and all officially licensed monks had to take their ordination under the Vinaya at Tōdai-ji. In 754, ordination was given by Ganjin, who arrived in Japan after overcoming hardships over 12 years and six attempts of crossing the sea from China, to Empress Kōken, former Emperor Shōmu and others. Later Buddhist monks, including Kūkai and Saichō took their ordination here as well.[9] During Kūkai's administration of the Sōgō, additional ordination ceremonies were added to Tōdai-ji, including ordination of the Bodhisattva Precepts from the Brahma Net Sutra and the esoteric Precepts, or Samaya, from Kukai's own newly established Shingon school of Buddhism. Kūkai added an Abhiseka Hall for the use of initiating monks of the six Nara schools into the esoteric teachings.[8] by 829.

During its height of power, Tōdai-ji's famous Shuni-e ceremony was established by the monk Jitchū, and continues to this day.

Decline

As the center of power in Japanese Buddhism shifted away from Nara to Mount Hiei and the Tendai sect, and when the capital of Japan moved to Kamakura, Tōdai-ji's role in maintaining authority declined as well. In later generations, the Vinaya lineage also died out, despite repeated attempts to revive it, thus no more ordination ceremonies take place at Tōdai-ji.

Architecture

Initial construction

In 743, Emperor Shōmu issued a law in which he stated that the people should become directly involved with the establishment of new Buddha temples throughout Japan. His personal belief was that such piety would inspire Buddha to protect his country from further disaster. Gyōki, with his pupils, traveled the provinces asking for donations. According to records kept by Tōdai-ji, more than 2,600,000 people in total helped construct the Great Buddha and its Hall; contributing rice, wood, metal, cloth, or labor; with 350,000 working directly on the statue's construction.[10][11][12] The 16 m (52 ft)[13] high statue was built through eight castings over three years, the head and neck being cast together as a separate element.[14] The making of the statue was started first in Shigaraki. After enduring multiple fires and earthquakes, the construction was eventually resumed in Nara in 745,[10] and the Buddha was finally completed in 751. A year later, in 752, the eye-opening ceremony was held with an attendance of 10,000 monks and 4,000 dancers to celebrate the completion of the Buddha.[15] The Indian priest Bodhisena performed the eye-opening for Emperor Shōmu. The project nearly bankrupted Japan's economy, consuming most of the available bronze of the time; the gold was entirely imported.[16] 48 lacquered cinnabar pillars, 1.5 m in diameter and 30 m long, support the blue tiled roof of the Daibutsu-den.[17]

The original complex also contained two 100 m pagodas, among the tallest structures at the time. These were destroyed by an earthquake. The Shōsōin was its storehouse, and now contains many artifacts from the Tenpyo period of Japanese history.

Reconstructions post-Nara Period

The Great Buddha Hall (Daibutsuden) has been rebuilt twice after fire. The current building was finished in 1709, and although immense—57 metres (187 ft) long and 50 metres (160 ft) wide—it is actually 30% smaller than its predecessor. Until 1998, it was the world's largest wooden building.[18] It has been surpassed by modern structures, such as the Japanese baseball stadium 'Odate Jukai Dome', amongst others. The Great Buddha statue has been recast several times for various reasons, including earthquake damage. The current hands of the statue were made in the Momoyama Period (1568–1615), and the head was made in the Edo period (1615–1867).

The existing Nandaimon (Great South Gate) was constructed at the end of the 12th century based on Song Dynasty style, after the original gate was destroyed by a typhoon during the Heian period. The dancing figures of the Nio, the two 8.5-metre-tall (28 ft) guardians at the Nandaimon, were built at around the same time by Unkei, Kaikei and their workshop members. The Nio are an A-un pair known as Ungyo, which by tradition has a facial expression with a closed mouth, and Agyo, which has an open mouthed expression.[19] The two figures were closely evaluated and extensively restored by a team of art conservators between 1988 and 1993. Until then, these sculptures had never before been moved from the niches in which they were originally installed. This complex preservation project, costing $4.7 million, involved a restoration team of 15 experts from the National Treasure Repairing Institute in Kyoto.[20]

Dimensions of the Daibutsu

The temple gives the following dimensions for the statue:[21]

- Height: 14.98 m (49 ft 2 in)

- Face: 5.33 m (17 ft 6 in)

- Eyes: 1.02 m (3 ft 4 in)

- Nose: 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in)

- Ears: 2.54 m (8 ft 4 in)

The statue's shoulders are 28 meters across and there are 960 six curls atop its head.[22] The Birushana Buddha's golden halo is 27 m (87 ft) in diameter with 16 images each 2.4 m (8 ft) tall.[23]

Recently, using x-rays, a human tooth, along with pearls, mirrors, swords, and jewels were discovered inside of the knee of the Great Buddha; these are believed to be the relics of Emperor Shomu.[24]

The statue weighs 500 tonnes (550 short tons).

Temple precincts and gardens

Various buildings of the Tōdai-ji have been incorporated within the overall aesthetic intention of the gardens' design. Adjacent villas are today considered part of Tōdai-ji.

Some of these structures are now open to the public. The time spent visiting one or more of these less well-known buildings can only enhance an appreciation of the temple complex itself.

Over the centuries, the buildings and gardens have evolved together as to become an integral part of a unique, organic and living temple community.

The Tōdai-ji Culture Center opened on October 10, 2011, comprising a museum to exhibit the many sculptures and other treasures enshrined in the various temple halls, along with a library and research centre, storage facility, and auditorium.[25][26][27]

Japanese national treasures at Todai-ji

The architectural master-works are classified as:

| Romaji | Kanji |

|---|---|

| Kon-dō (Daibutsuden) | 金堂 (大仏殿) |

| Nandaimon | 南大門 |

| Kaizan-dō | 開山堂 |

| Shōrō | 鐘楼 |

| Hokke-dō (Sangatsu-dō) | 法華堂 (三月堂) |

| Nigatsu-dō | 二月堂 |

| Tegaimon | 転害門 |

Major historical events

- 728: Kinshōsen-ji, the forerunner of Tōdai-ji, is established as a gesture of appeasement for the troubled spirit of Prince Motoi.

- 741: Emperor Shōmu calls for nationwide establishment of provincial temples,[28] and Kinshōsen-ji appointed as the head provincial temple of Yamato.

- 743: The Emperor commands that a very large Buddha image statue shall be built—the Daibutsu or Great Buddha—and initial work is begun at Shigaraki-no-miya.[29]

- 745: The capital returns to Heijō-kyō, construction of the Great Buddha resumes in Nara. Usage of the name Tōdai-ji appears on record.[30]

- 752: The Eye-opening Ceremony celebrating the completion of the Great Buddha held.[31]

- 855: The head of the great statue of the Buddha Vairocana suddenly fell to the ground; and gifts from the pious throughout the empire were collected to create another, more well-seated head for the restored Daibutsu.[32]

Cultural references

Tōdai-ji has been used as a location in several Japanese films and television dramas. It was also used in the 1950s John Wayne movie The Barbarian and the Geisha when Nandaimon, the Great South Gate, doubled as a city's gates.

It also appears in Microsoft's game Age of Empires II.

The Great Music Experience

On May 20, 1994, the international music festival The Great Music Experience was held at Tōdai-ji, supported by the UNESCO.

Performers included the Tokyo New Philharmonic Orchestra, X Japan, INXS, Jon Bon Jovi, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Tomoyasu Hotei, Roger Taylor, classic Japanese drummers, and a Buddhist monk choir. This event, organized by British producer Tony Hollingsworth, was simultaneously broadcast in 55 countries on May 22 and 23, 1994.

Sarah Brightman in Concert with Orchestra

On November 3, 2010, English soprano Sarah Brightman was invited to sing at the Tōdai-ji in her concert tour called Sarah Brightman in Concert with Orchestra. The concert was recorded and later broadcast in Japan by the Tokyo Broadcasting System.

Gallery

Deer in front of the Great Southern Gate (Nandaimon), a National Treasure (13th century).

Deer in front of the Great Southern Gate (Nandaimon), a National Treasure (13th century). The Tegai-mon is also a National Treasure (8th century).

The Tegai-mon is also a National Treasure (8th century). Hokke-dō is also a National Treasure (8th century).

Hokke-dō is also a National Treasure (8th century). Nigatsu-dō is also a National Treasure (17th century).

Nigatsu-dō is also a National Treasure (17th century). Daibutsu; Note caretaker standing at base for scale.

Daibutsu; Note caretaker standing at base for scale. Stone Jizō from grounds of Tōdai-ji.

Stone Jizō from grounds of Tōdai-ji. Bishamonten watching over Tōdai-ji and its precincts.

Bishamonten watching over Tōdai-ji and its precincts. Komokuten, one of the pair of guardians in the Daibutsuden

Komokuten, one of the pair of guardians in the Daibutsuden Bronze bell

Bronze bell- Shuni-e held March 1 to 14 in Nigatsu-dō.

Onigawara roof tiles

Onigawara roof tiles- Bodhisattvas incised on Lotus Petal of the throne of the main Buddha, 8th century.

- Incised image on Lotus Petal of the throne of the main Buddha, 8th century. Photo.

- Openwork playing flute Bodhisattva in Octagonal Lantern Tower (8th century).

The main hall, with festival decorations

The main hall, with festival decorations A supporting post in the Daibutsuden has a hole said to be the same size as one of the Daibutsu's nostrils. Legend has it that those who pass through it will be blessed with enlightenment in their next life.

A supporting post in the Daibutsuden has a hole said to be the same size as one of the Daibutsu's nostrils. Legend has it that those who pass through it will be blessed with enlightenment in their next life.- Shaka at Birth (National Treasure)

Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara, Japan

Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara, Japan

See also

- Tamukeyama Hachiman Shrine, Shinto shrine near the temple precincts

- Kōtoku-in, location of the Kamakura Great Buddha

- Shōhō-ji, location of the Gifu Great Buddha

- Kanjin#Kanjinshoku of Todai-ji

- Nanto Shichi Daiji, Seven Great Temples of Nanto

- For an explanation of terms concerning Japanese Buddhism, Japanese Buddhist art, and Japanese Buddhist temple architecture, see the Glossary of Japanese Buddhism.

- List of National Treasures of Japan (ancient documents)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (temples)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (archaeological materials)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (paintings)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (sculptures)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (writings)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (crafts-others)

- Old Government Buildings (Wellington), New Zealand – second-largest wooden building in the world

- Ostankino Palace, third-largest wooden building in the world[33]

- Tourism in Japan

- Siege of Nara

Notes

- ↑ The temple has acquired this name by the fact it was located to the east of the Heijō-kyō.

- ↑ http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/birushana.shtml

- ↑ JNTO Website | Find a Location | Nara | Nara-koen Park (Todai-ji Temple), Japan National Tourist Organization, retrieved on February 5, 2009

- ↑ Farris, William Wayne (1985). Population, Disease, and Land in Early Japan, 645–900. Harvard University Press. pp. 84 ff. ISBN 0-674-69005-2.

- ↑ Hall, John Whitney; Mass, Jeffrey P (1974). Medieval Japan: Essays in Institutional History. Stanford University Press. pp. 97 ff. ISBN 0-8047-1510-6.

- ↑ Hall, John W., et al., eds. (1988). The Cambridge history of Japan, pp. 398–400.

- ↑ Mino, Yutaka (1986). The Great Eastern Temple: Treasures of Japanese Buddhist Art From Todai-Ji. Garland Publishing Inc. p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Abe, Ryuichi (1999). The Weaving of Mantra: Kukai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. pp. 35, 55. ISBN 0-231-11286-6.

- ↑ Hakeda, Yoshito S. (1972). Kūkai and His Major Works. Columbia University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-231-05933-7.

- 1 2 "Official Tōdai-ji Homepage" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- ↑ Huffman, James L. (2010). Japan in World History. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ The same record keeps track of some prominent persons, among many others, being involved in the construction. E.g. Kuninaka-no-muraji Kimimaro, whose grandfather was an immigrant from the Baekje Kingdom on the Korean peninsula, is believed to have directed the construction of the Great Buddha and the Hall. Takechi-no-sanekuni is believed to have directed the sculpture part.

- ↑ The height of the original Buddha.

- ↑ Brown, Delmer et al. (1979). Gukanshō, p. 286.

- ↑ Mino, Yutaka (1986). The Great Eastern Temple: Treasures of Japanese Buddhist Art From Todai-Ji. Garland Publishing Inc. p. 34. ISBN 0-253-20390-2.

- ↑ Dresser, Christopher (1882). Japan: Its Architecture, Art and Art Manufactures. New York and London. p. 89.

- ↑ Mino, Yutaka (1986). The Great Eastern Temple: Treasures of Japanese Buddhist Art From Todai-Ji. Garland Publishing Inc. p. 33,40. ISBN 0-253-20390-2.

- ↑ "Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (JAANUS), "Niou" (仁王); "A un" (阿吽), 2001, retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ↑ Sterngold, James. "Japan Restores Old Temple Gods". The New York Times. December 28, 1991, retrieved 2011-04-14; excerpt, "The Nio are known as Ungyo, which by tradition has a closed mouth, and Agyo, which has an open mouth. The figures, which appear in some form in many Buddhist temples, are powerful bare-chested gods, wielding heavy cudgels to ward off evil spirits. Ungyo was restored first. The more delicate parts were removed, including the long ribbon streaming from its top knot. Then the statue was swathed in thick layers of cotton, laid on its back and rolled slowly to a large metal shed built for the conservation. Ungyo was replaced this year and then Agyo was removed to the shed for restoration, a process that is likely to take two years."

- ↑ 大仏さまの大きさ:

- ↑ Dresser, Christopher (1882). Japan: Its Architecture, Art and Art Manufactures. New York and London. p. 94.

- ↑ Dresser, Christopher (1882). Japan: Its Architecture, Art and Art Manufactures. New York and London. p. 89.

- ↑ Ruppert, Brian D. (2000). Jewel in the Ashes: Buddha Relics and Power in Medieval Japan. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 61–62. ISBN 0-674-00245-8.

- ↑ "Todaiji unveils museum to show ancient treasures". The Japan Times. October 12, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-10-23. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ↑ 東大寺総合文化センター [Tōdaiji Culture Center] (in Japanese). Tōdai-ji. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Nara's Todaiji Cultural Center Completed". Nagata Acoustics. February 25, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ↑ Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Titsingh, Isaac. (134). Annales des empereurs du japon, p. 72; Brown, p. 273.

- ↑ Titsingh, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Titsingh, p. 74; Varley, p. 142 n59.

- ↑ Titsingh, p. 114; Brown, p. 286.

- ↑ "В столице остается все меньше деревянных зданий". Newstube.ru. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tōdai-ji. |

- The official Tōdai-ji homepage (Japanese)

- Todai-ji Guide GoJapanGo

- Photos of Tōdai-ji Temple, its Lotus Hall and Ordination Hall

- Photos of Tōdai-ji Temple and sika deer

Coordinates: 34°41′21″N 135°50′23″E / 34.68917°N 135.83972°E