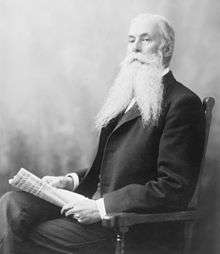

Sanford B. Dole

| Sanford Dole | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Territorial Governor of Hawaii | |

|

In office 14 June 1900 – 23 November 1903 | |

| Appointed by | William McKinley |

| Preceded by | Position Established |

| Succeeded by | George Carter |

| President of Hawaii | |

|

In office 4 July 1894 – 14 June 1900 | |

| Preceded by | Position Established (Liliuokalani as Queen) |

| Succeeded by | Position Abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Sanford Ballard Dole 23 April 1844 Honolulu, Kingdom of Hawaii |

| Died |

9 June 1926 (aged 82) Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii |

| Political party | Republican Party |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Prentice Cate Dole |

Sanford Ballard Dole (April 23, 1844 – June 9, 1926) was a lawyer and jurist in the Hawaiian Islands as a kingdom, protectorate, republic and territory. An enemy of the Hawaiian royalty and friend of the elite immigrant community, Dole advocated the westernization of Hawaiian government and culture. After the overthrow of the monarchy, he served as President of Hawaii until his government secured Hawaii's annexation by the United States.

Early years

Dole was born April 23, 1844 in Honolulu to Protestant Christian missionaries from Maine in the United States. His father was Daniel Dole (1808–1878) principal at Punahou School and mother was Emily Hoyt Ballard (1808–1844). His mother died from complications within a few days of his birth. Dole was named after his uncle, Sandford K. Ballard who was a classmate of his father's at Bowdoin College (and brother of his mother) who died in 1841.[1] He was nursed by a native Hawaiian, and his father remarried to Charlotte Close Knapp in 1846. In 1855 the family moved to Kōloa on the island of Kauaʻi, where they operated another school.[2]

Dole attended Punahou school for one year, and then Williams College in 1866–1867. He worked in a law office in Boston for another year, and although he never attended law school, he received an honorary LL.D. degree from Williams in 1897.[3] In December 1880 he was commissioned as a Notary Public in Honolulu. Dole won the 1884 and 1886 elections to the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a representative from Kauaʻi.[4]

Bayonet Constitution

In June 1887 local businessmen, sugar planters and politicians backed by the Honolulu Rifles forced the dismissal of the cabinet of controversial Walter M. Gibson and forced the adoption of the 1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The new documents limited voting rights exclusively to only the literate males of the following populations: Hawaiian, European, and American descent...while imposing income and wealth requirements to be eligible to vote for the House of Nobles, thus, effectively consolidating power among only the elite residents of the island. In addition, the new Constitution minimized the power of the Monarch in favor of more influential governance by the cabinet. Dole and other lawyers of American descent drafted this document, which became known as the "Bayonet Constitution".[5]

King Kalākaua appointed Dole a justice of the Supreme Court of the Kingdom of Hawaii on December 28, 1887, and to a commission to revise judiciary laws on January 24, 1888. After Kalākaua's death, his sister Queen Liliʻuokalani appointed him to her Privy Council on August 31, 1891.[4]

End of the monarchy

.jpg)

The monarchy ended on January 17, 1893 after the Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii organized by many of the same actors involved in the 1887 revolt. Although Dole declined to officially be part of the Committee of Safety on January 14, he helped draft their declaration.[6]:589

Dole was named president of the Provisional Government of Hawaii that was formed after the coup, and was recognized within 48 hours by all nations with diplomatic ties to the Kingdom of Hawaii, including the United Kingdom.[7] His cabinet (called the "executive council") included James A. King as minister of the interior,[8] William Owen Smith as attorney general,[9] and banker Peter Cushman Jones as minister of finance. Dole acted as minister of foreign affairs himself until February 15, 1894.[4] Later Samuel Mills Damon would serve as minister of finance.[10]

With Grover Cleveland's election as President of the United States, the Provisional Government's hopes of annexation were derailed for a time. Indeed, Cleveland tried to directly help reinstate the monarchy, after an investigation led by James Henderson Blount. The Blount Report of July 17, 1893, commissioned by President Cleveland, concluded that the Committee of Safety conspired with U.S. ambassador John L. Stevens to land the United States Marine Corps, to forcibly remove Queen Liliʻuokalani from power, and declare a Provisional Government of Hawaii consisting of members from the Committee of Safety.

On November 16, 1893, Albert Willis presented the Queen with Cleveland's request that she grant amnesty to the Revolutionists in return for reinstatement. The Queen refused, and, according to Willis, demanded capital punishment for those involved. On December 23, unaware that Cleveland had referred the matter to Congress, Willis presented the Provisional Government with Cleveland's demand to restore the queen to the throne – the Provisional Government refused.

Queen Liliuokalani wrote in her book Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, that she did not demand capital punishment.[11]

The Morgan Report of February 26, 1894, concluded that the overthrow was locally based, motivated by a history of corruption of the monarchy, and that American troops only served to protect American property and citizens and had no role in the end of the Hawaiian Monarchy.[12]

The Provisional Government held a constitutional convention and on July 4, 1894, established the Republic of Hawaii.

President of the republic

Lorrin A. Thurston declined the presidency of the republic, and Dole was chosen to lead the government instead. Dole would serve as the first and only president from 1894 to 1898. Dole in turn appointed Thurston to lead a lobbying effort in Washington, DC and secure Hawaiʻi's annexation. Dole was successful as a diplomat – every nation that recognized the Kingdom of Hawaii also recognized the republic.

Dole's government weathered several attempts to restore the monarchy, including an attempted armed rebellion, the January 24, 1895 counter-revolution. Leader Robert William Wilcox and the other conspirators were captured and sentenced to death, but had their sentences reduced or commuted by Dole. The Queen abdicated and swore allegiance to the Republic of Hawaii in February. While under arrest, she wrote, "I hereby do fully and unequivocally admit and declare that the Government of the Republic of Hawaii is the only lawful Government of the Hawaiian Islands, and that the late Hawaiian monarchy is finally and forever ended, and no longer of any legal or actual validity, force or effect whatsoever."[13]

Queen Liliʻuokalani provided a more detailed story of the events from her perspective in the later chapters of her book.[11]

.jpg)

Governor and federal judge

In March 1899 Henry Ernest Cooper, who had been chairman of the Committee of Safety in 1893, became attorney general.[9] President William McKinley appointed Dole to become the first territorial governor after U.S. annexation of Hawaii, and the Hawaiian Organic Act organized its government. Dole assumed the office on June 14, 1900 but resigned November 23, 1903 to accept an appointment by Theodore Roosevelt as judge for the US District Court after the death of Morris M. Estee. He served in that post until December 16, 1915, and was replaced by Horace Worth Vaughan.[14] He also served on commissions for Honolulu parks, and the public archives.[4] He died after a series of strokes on June 9, 1926. His ashes were interred in the cemetery of Kawaiahaʻo Church.[15]

Family and legacy

His cousin Edmund Pearson Dole (1850–1928) came to Hawaii to practice as a lawyer in 1895, and became Attorney General of Hawaii from 1900 to 1903.[16] Sanford Dole was the cousin once removed of James Dole who came to Hawaii in 1899 and founded the Hawaiian Pineapple Company on Oahu, which later became the Dole Food Company.[17] James' father Charles Fletcher Dole also came to Hawaii in 1909.[18]

Dole Middle School, located in Kalihi Valley on the island of Oʻahu, was named after him in April 1956, about a century after his father founded the school in Kōloa.[19] In the film Princess Kaiulani, his role was played by Will Patton.[20]

In Hawaiian, the pale and hair-like Spanish moss is called ʻumiʻumi-o-Dole, meaning "Dole's beard".

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sanford B. Dole. |

- ↑ Nehemiah Cleaveland; Alpheus Spring Packard (1882). History of Bowdoin college: With biographical sketches of its graduates, from 1806 to 1879, inclusive. J. R. Osgood & Company. p. 487.

- ↑ Hawaiian Mission Children's Society (1901). Portraits of American Protestant missionaries to Hawaii. Honolulu: Hawaiian gazette company. p. 73.

- ↑ Williams College (1905). General catalogue of the officers and graduates of Williams college, 1905. The College. p. 178.

- 1 2 3 4 "Dole, Sanford Ballard office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ↑ David W. Forbes (2003). Hawaiian national bibliography, 1780-1900. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-8248-2636-9.

- ↑ Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1967). Hawaiian Kingdom 1874-1893, the Kalakaua Dynasty. 3. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1.

- ↑ http://morganreport.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=DIPLOMATIC_RECOGNITION_OF_THE_PROVISIONAL_GOVERNMENT

- ↑ "King, James A. office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- 1 2 "Attorney General office record" (PDF). state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Minister of finance office record" (PDF). state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- 1 2 Liliʻuokalani (Queen of Hawaii) (1898). Hawaii's story by Hawaii's queen, Liliuokalani. Lee and Shepard, reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, LLC (July 25, 2007). ISBN 978-0-548-22265-2.

- ↑ Andrade Jr., Ernest (1996). Unconquerable Rebel: Robert W. Wilcox and Hawaiian Politics, 1880-1903. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-417-6.

- ↑ William Adam Russ (1992). The Hawaiian Republic (1894-98) And Its Struggle to Win Annexation. Associated University Presses. pp. 71–72. ISBN 0-945636-52-0.

- ↑ Elizabeth H. Ryan, ed. (1918). Reports of causes determined in the United States District court for the district of Hawaii. Hawaiian Gazette company. p. iii.

- ↑ William Disbro (November 6, 2001). "Mission Houses Cemetery, Honolulu, Hawaii". Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Dole, Edmund Pearson office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ↑ "James Drummond Dole "The Pineapple King"". Jamaica Plain Historical Society. Roxbury Latin School. April 2008. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Patriot Dole". The Friend. LXVI (3). Honolulu. March 1906. p. 3.

- ↑ "Sanford Ballard Dole". Dole Middle School web site. April 23, 1956. Retrieved September 9, 2010. (Dedication speech)

- ↑ Princess Kaiulani at the Internet Movie Database

Further reading

- Ethel Moseley Damon (1957). Sanford Ballard Dole and his Hawaii: With an analysis of Justice Dole's legal opinions. Published for the Hawaiian Historical Society by Pacific Books.

- Helena G. Allen (June 1988). Sanford Ballard Dole: Hawaii's only president, 1844-1926. A. H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0-87062-184-0.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Liliuokalani as Queen of Hawaii |

President of Hawaii 1893 – 1900 |

Republic of Hawaii annexed by United States |

| First Territory of Hawaii established |

Territorial Governor of Hawaii 1900 – 1903 |

Succeeded by George R. Carter |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by Morris M. Estee |

US District Court Judge 1903–1915 |

Succeeded by Horace W. Vaughan |