Persian phonology

The Persian language has six vowel phonemes and twenty-three consonant phonemes. It features contrastive stress and syllable-final consonant clusters.

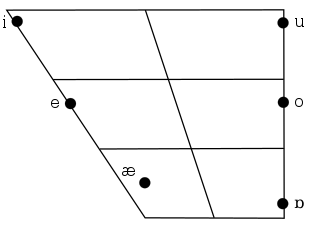

Vowels

/e/ is pronounced between the vowel of bate (for most English dialects) and the vowel of bet; /o/ is pronounced between the vowel of boat (for most English dialects) and the vowel of raw.

Word-final /o/ is rare except for تو ту /to/ ('you' [singular]), loanwords (mostly of Arabic origin), and proper and common nouns of foreign origin, and word-final /æ/ is very rare in Iranian Persian, an exception being نه на /næ/ ('no'). The word-final /æ/ in Early New Persian mostly shifted to /e/ in contemporary Iranian Persian (often romanized as ⟨eh⟩, meaning [e] is also an allophone of /æ/ in word-final position in contemporary Iranian Persian), but is preserved in the Eastern dialects.

The chart to the right reflects the vowels of many educated Persian speakers from Tehran.[1][2]

The three vowels /æ/, /e/ and /o/ are traditionally referred to as 'short' vowels and the other three (/ɒː/, /iː/ and /uː/) as 'long' vowels. In fact the three 'short' vowels are short only when in an open syllable (i.e. a syllable ending in a vowel) that is non-final (but can be unstressed or stressed), e.g. صدا садо [seˈdɒː] 'sound', خدا Худо [xoˈdɒː] 'God'. In a closed syllable (i.e. a syllable ending in a consonant) that is unstressed, they are around sixty percent as long as a long vowel; this is true for the 'long' vowel /iː/ as well. Otherwise the 'short' and 'long' vowels are all pronounced long. Example: سفتر сафтар [seˑfˈtʰæːɾ] 'firmer'.[3]

When the short vowels are in open syllables, they are also unstable and tend in informal styles to assimilate in quality to the following long vowel. Thus دویست дувест [deˈviːst] 'two hundred' becomes [diˈviːst], شلوغ шулуғ [ʃoˈluːɢ] 'crowded' becomes [ʃuˈluːɢ], رسیدن расидан [ræsiːˈdæːn] 'to arrive' becomes [resiːˈdæːn] and so on.[3]

Diphthongs

The status of diphthongs in Persian is disputed.[4][5] Some authors list ei̯, ou̯, āi̯, oi̯, ui̯,[4] others list only two ei̯ and ou̯, but some do not recognize diphthongs in Persian altogether.[4][5] A major factor that complicates the matter is the change of two classical and pre-classical Persian diphthongs: ai̯ > ei̯, au̯ > ou̯. This shift occurred in Iran but not in some modern varieties (particularly of Afghanistan).[4] Morphological analysis also supports the view that the alleged Persian diphthongs are combinations of the vowels with /j/ and /w/.[5]

The Persian orthography does not distinguish between the diphthongs and the consonants /j/ and /w/; that is, they both are written with ی and و respectively.

/ow/ becomes [oː] in colloquial Tehrani dialect but is preserved in other Western dialects and standard Iranian Persian.

Spelling and example words

For Western Persian:

| Phoneme (in IPA) | Letter | Romanization | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| /æ/ | ـَ ,ـَه; а | a | /næ/ نه на "no" |

| /ɒː/ | ـا, آ ,ىٰ; о | ā | /tɒː/ تا то "until" |

| /e̞/ | ـِ ,ـِه; и | e | /ke/ که ки "that" |

| /iː/ | ـِی; и, ӣ | ī | /ʃiːr/ شیر шир "milk" |

| /o/ | ـُ ,ـو; у | o | /to/ تو ту "you" (singular) |

| /uː/ | ـُو; у | ū | /ruːd/ رود руд "river" |

| Phoneme (in IPA) | Letter | Romanization | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| /ej/ | ـَیْ; ай | ey | /kej/ کی кай "when?" |

| /ow/ | ـَوْ; ав | ow | /now/ نو нав "fresh" |

The variety of Afghanistan has preserved as well these two Classic Persian vowels:

| Phoneme (in IPA) | Letter | Romanization | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| /eː/ | ـی; е | ē | /ʃeːr/ شیر шер "lion" |

| /oː/ | ـو; ӯ | ō | /roːd/ رود рӯд "bow-string" |

In the modern Persian alphabet, the short vowels /e/, /o/, /æ/ are usually not written, as is normally done in Arabic alphabet. (See Arabic phonology § Vowels.)

Historical shifts

Early New Persian inherited from Middle Persian eight vowels: three short i, a, u and five long ī, ē, ā, ō, ū (in IPA: /i a u/ and /iː eː aː oː uː/). It is likely that this system passed into the common Persian era from a purely quantitative system into one where the short vowels differed from their long counterparts also in quality: i > /j/; u > /ʊ/; ā > /ɑː/. These quality contrasts have in modern Persian varieties become the main distinction between the two sets of vowels.[6]

The inherited eight-vowel inventory is retained without major upheaval in Dari, the only systematic innovation being the lowering of the lax close front i and u to mid vowels /e/ and /o/.

In Western Persian, two of the vowel contrasts have been lost: those between the tense mid and close vowels. Thus ē, ī have merged as /iː/, while ō, ū have merged as /uː/. In addition, similarly to Dari, the lax close vowels have become mid: i > /e/, u > /o/. The lax open vowel has become fronted: a > /æ/, and in word-final position further raised to /e/.

In both varieties ā is more or less labialized.

Tajiki has also lost two of the vowel contrasts, but differently from Western Persian: here the tense/lax contrast among the close vowels has been eliminated. That is, i, ī have merged as /i/, and u, ū have merged as /u/. The other tense back vowels have shifted as well. Mid ō has become more front: /u/ or /ʉ/, a vowel usually romanized as ů. Open ā has become a mid, labial vowel /o/.

Loanwords from Arabic generally abide to these shifts as well.

The following chart summarizes the later shifts into modern Tajik, Dari, and Western Persian.[7]

| Early New Persian | Dari Persian | Western Persian | Tajiki Persian | In script | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | /æ/ | /æ/ | /æ/ | ـَ ,ـَه; а | نه на "no" |

| /aː/ | /ɒː/ | /ɒː/ | /ɔː/ | ـا, آ ,ىٰ; о | تا то "until" |

| /i/ | /i/ | /e/ | /i/ | ِـِ ,ـِه; и | که ки "that" |

| /iː/ | /iː/ | /iː/ | ـِی; и, ӣ | شیر шир "milk" | |

| /eː/ | /eː/ | /eː/ | ـی; е | شیر шер "lion" | |

| /aj/ | /æj/ | /ej/ | /æj/ | ـَیْ; ай | کی; кай "when?" |

| /u/ | /u/ | /o/ | /u/ | ـُ ,ـو; у | تو ту "you" (singular) |

| /uː/ | /uː/ | /uː/ | ـُو; у | رود руд "river" | |

| /oː/ | /oː/ | /uː/ | ـو; ӯ | رود рӯд "bow-string" | |

| /aw/ | /æw/ | /ow/ | /æw, æv/ | ـَوْ; ав | نو нав "fresh" |

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | b | |||

| Affricate | tʃ dʒ | ||||||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | χ | h | ||

| Trill | r | ||||||

| Approximant | l | j |

Allophonic variation

Alveolar stops /t/ and /d/ are either apical alveolar or laminal denti-alveolar. The voiceless obstruents /p, t, tʃ, k/ are aspirated much like their English counterparts: they become aspirated when they begin a syllable, though aspiration is not contrastive.[8] The Persian language does not have syllable-initial consonant clusters (see below), so unlike in English, /p, t, k/ are aspirated even following /s/, as in هستم ҳастам /hæstæm/ ('I exist').[9] They are also aspirated at the end of syllables, although not as strongly.

The velar stops /k, ɡ/ are palatalized before front vowels or at the end of a syllable.

In Classical Persian, غ ғ and ق қ denoted the original Arabic phonemes, the voiced uvular fricative [ʁ] and the voiceless uvular stop [q], respectively. In modern Tehrani Persian (which is used in the Iranian mass media, both colloquial and standard), there is no difference in the pronunciation of غ and ق, and they are both normally pronounced as a voiced uvular stop [ɢ]. The classic pronunciations of غ ғ and ق қ are preserved in the eastern varieties, Dari and Tajiki, as well as in the southern varieties (e.g. Zoroastrian Dari language and other Central / Central Plateau or Kermanic languages).

The alveolar flap /ɾ/ has a trilled allophonic variant [r] at the beginning of a word, as in Spanish, Catalan, and other Romance languages in Spain (it can be a free variation between a trill [r] and a flap [ɾ]);[8] the trill [r] as a separate phoneme occurs word-medially especially in loanwords of Arabic origin as a result of gemination of [ɾ]. An alveolar approximant [ɹ] also occurs as an allophone of /ɾ/ before /t, d, s, z, ʃ, l/, and /ʒ/; [ɹ] is sometimes in free variation with [ɾ] in these and other positions, such that فارسی Форсӣ ('Persian') is pronounced [fɒːɹˈsiː] or [fɒːɾˈsiː] and سقرلات сақирлот ('scarlet') becomes [sæɣeˑɹˈlɒːt] or [sæɣeˑɾˈlɒːt]. /r/ is sometimes realized as a long approximant [ɹː].

The velar nasal [ŋ] is an allophone of /n/ before /k,g/

/f, k, s, ʃ, x/ may be voiced to, respectively, [v, ɡ, z, ʒ, ɣ] before voiced consonants; /n/ may be bilabial [m] before bilabial consonants. Also /b/ may in some cases change into [β], or even [v]; for example باز боз ('open') may be pronounced [bɒːz] as well as [vɒːz] or [vɒː], colloquially.

Dialectal variation

The pronunciation of و в [w] in Classical Persian shifted to [v] in Iranian Persian, but is retained in Dari or Afghan Persian; but in modern Persian [w] is lost if preceded by a consonant and followed by a vowel in one whole syllable, e.g. خواب хоб /x(w)ɒb/ 'sleep', as Persian has no syllable-initial consonant clusters (see below).

Spelling and example words

| Phoneme | Perso-Arabic Alphabet | Tajik Alphabet | Example | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /p/ | پ | п | /peˈdæɾ/ | پدر | падар | 'father' |

| /b/ | ب | б | /bærɒːˈdær/ | برادر | бародар | 'brother' |

| /t/ | ت, ط | т | /tɒː/ | تا | то | 'till' |

| /d/ | د | д | /duːst/ | دوست | дӯст | 'friend' |

| /k/ | ک | к | /keʃˈvæɾ/ | کشور | кишвар | 'country' |

| /ɡ/ | گ | г | /ɡoˈruːh/ | گروه | гурӯҳ | 'group' |

| /ʔ/ | ع, ء | ъ | /mæʔˈnɒː/ | معنا | маъно | 'meaning' |

| /t͡ʃ/ | چ | ч | /tʃuːb/ | چوب | чӯб | 'wood' |

| /d͡ʒ/ | ج | ҷ | /dʒæˈvɒːn/ | جوان | ҷавон | 'young' |

| /f/ | ف | ф | /feˈʃɒːɾ/ | فشار | фишор | 'pressure' |

| /v/ | و | в | /viːˈʒa/ | ویژه | вижа | 'special' |

| /s/ | س , ص , ث | с | /sɒːˈje/ | سایه | соя | 'shadow' |

| /z/ | ز , ذ , ض , ظ | з | /ɒːˈzɒːd/ | آزاد | озод | 'free' |

| /ʃ/ | ش | ш | /ʃɒːh/ | شاه | шоҳ | 'king' |

| /ʒ/ | ژ | ж | /ʒɒːˈle/ | ژاله | жола | 'dew' |

| /χ/ | خ | х | /χɒːˈne/ | خانه | хона | 'house' |

| /b/ | غ | ғ | /ʁærb/ | غرب | ғарб | 'west' |

| /b/ | ق | қ | /ɢæˈlæm/ | قلم | қалам | 'pen' |

| /h/ | وه , ح | ҳ | /hæft/ | هفت | ҳафт | 'seven' |

| /m/ | م | м | /mɒːˈdær/ | مادر | модар | 'mother' |

| /n/ | ن | н | /nɒːn/ | نان | нон | 'bread' |

| /l/ | ل | л | /læb/ | لب | лаб | 'lip' |

| /ɾ/ | ر | р | /iːˈɾɒːn/ | ایران | Эрон | 'Iran' |

| /j/ | ی | й | /jɒː/ | یا | ё | 'or' |

Consonants can be geminated, often in words from Arabic. This is represented in the IPA either by doubling the consonant, سیّد саййид [sejjed], or with the length marker ⟨ː⟩, [sejːed].[10]

Phonotactics

Syllable structure

Syllables may be structured as (C)(S)V(S)(C(C)).[8][11]

Persian syllable structure consists of an optional syllable onset, consisting of one consonant; an obligatory syllable nucleus, consisting of a vowel optionally preceded by and/or followed by a semivowel; and an optional syllable coda, consisting of one or two consonants. The following restrictions apply:

- Onset

- Consonant (C): Can be any consonant. (Onset is composed only of one consonant; consonant clusters are only found in loanwords, sometimes an epenthetic /æ/ is inserted between consonants.)

- Nucleus

- Semivowel (S)

- Vowel (V)

- Semivowel (S)

- Coda

- First consonant (C): Can be any consonant.

- Second consonant (C): Can also be any consonant (mostly /d/, /k/, /s/, /t/, & /z/).

Word Accent

The Persian word-accent has been described as a stress accent by some,[12] and as a pitch accent by others.[13] In fact the accented syllables in Persian are generally pronounced with a raised pitch as well as stress; but in certain contexts words may become deaccented and lose their high pitch.[14][15]

From an intonational point of view, Persian words (or accentual phrases) usually have the intonation (L +) H* (where L is low and H* is a high-toned stressed syllable), e.g. کتاب китоб /keˈtɒ́b/ 'book'; unless there is a suffix, in which case the intonation is (L +) H* + L, e.g. کتابم китобам /keˈtɒ́b-æm/ 'my book'. The last accent of a sentence is usually accompanied by a low boundary tone, which produces a falling pitch on the last accented syllable, e.g. کتاب بود китоб буд /keˈtɒ̂b buːd/ 'it was a book'.[14][15]

When two words are joined in an اضافه изофа ezafe construction, they can either be pronounced accentually as two separate words, e.g. مردم اینجا мардуми инҷо /mærˈdóm-e inˈd͡ʒɒ́/ 'the people (of) here', or else the first word loses its high tone and the two words are pronounced as a single accentual phrase: /mærˈdom-e inˈd͡ʒɒ́/. Words also become deaccented following a focused word; for example, in the sentence نامۀ مامانم بود رو میز Номии момонам буд ру миз /nɒˈme-ye mɒˈmɒn-æm bud ru miz/ 'it was my mom's letter on the table' all the syllables following the word مامان момон /mɒˈmɒn/ 'mom' are pronounced with a low pitch.[14]

Knowing the rules for the correct placement of the accent is essential for proper pronunciation.[16]

- Accent is heard on the last stem-syllable of most words.

- Accent is heard on the first syllable of interjections, conjunctions and vocatives. E.g. بله бали /ˈbæle/ ('yes'), نخیر /ˈnæxeir/ нахайр ('no, indeed'), ولی валӣ /ˈvæli/ ('but'), چرا /ˈtʃeɾɒ/ чиро ('why'), اگر агар /ˈæɡæɾ/ ('if'), مرسی /ˈmeɾsi/ мерси ('thanks'), خانم /ˈxɒnom/ хонум ('Ma'am'), آقا /ˈɒɢɒ/ оқо ('Sir'); cf. 4-4 below.

- Never accented are:

- personal suffixes on verbs (/-æm/ ('I do..'), /-i/ ('you do..'), .., /-ænd/ ('they do..') (with one exception, cf. 4-1 below);

- a small set of very common noun enclitics: the /ezɒfe/ اضافه изофа (/-e/, /-je) ('of'), /-ɾɒ/ a direct object marker, /-i/ ('a'), /-o/ ('and');

- the possessive and pronoun-object suffixes, /-æm/, /-et/, /-eʃ/, &c.

- Always accented are:

- the personal suffixes on the positive future auxiliary verb (the single exception to 3-1 above);

- the negative verb prefix /næ-/, /ne-/, if present;

- if /næ-/, /ne-/ is not present, then the first non-negative verb prefix (e.g. /mi-/ ('-ing'), /be-/ ('do!') or the prefix noun in compound verbs (e.g. کار кор /kɒr/ in کار میکردم кор мекардам /ˈkɒr mi-kærdæm/);

- the last syllable of all other words, including the infinitive ending /-æn/ and the participial ending /-te/, /-de/ in verbal derivatives, noun suffixes like /-i/ ('-ish') and /-eɡi/, all plural suffixes (/-hɒ/, /-ɒn/), adjective comparative suffixes (/-tæɾ/, /-tæɾin/), and ordinal-number suffixes (/-om/). Nouns not in the vocative are stressed on the final syllable: خانم хонум /xɒˈnom/ ('lady'), آقا оқо /ɒˈɢɒ/ ('gentleman'); cf. 2 above.

- In the informal language, the present perfect tense is pronounced like the simple past tense. Only the word-accent distinguishes between these tenses: the accented personal suffix indicates the present perfect and the unstressed one the simple past tense:

| Formal | Informal | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| /diːˈde.æm/ دیده ام дида ам | /diːˈdæm/ | 'I have seen' |

| /ˈdiːdæm/ دیدم дидам | /ˈdiːdæm/ | 'I saw' |

Colloquial Iranian Persian

When spoken formally, Iranian Persian is pronounced as written. But colloquial pronunciation as used by all classes makes a number of very common substitutions. Note that Iranians can interchange colloquial and formal sociolects in conversational speech. They include:[16][17]

- In the Tehrani accent and also most of the accents in Central and Southern Iran, the sequence /ɒn/ in the colloquial language is nearly always pronounced [un]. The only common exceptions are high prestige words, such as قرآن Қуръон [ɢoɾʔɒn] ('Qur'an'), and ایران Эрон [ʔiˈɾɒn] ('Iran'), and foreign nouns (both common and proper), like the Spanish surname بلتران Beltran [belˈtɾɒn], which are pronounced as written. A few words written as /ɒm/ are pronounced [um], especially forms of the verb آمدن /ɒmædæn/ омадан ('to come').

- In the Tehrani accent, the unstressed direct object suffix marker را ро /ɾɒ/ is pronounced /ɾo/ after a vowel, and /o/ after a consonant.

- The stems of many verbs have a short colloquial form, especially است аст /æst/ ('he/she is'), which is colloquially shortened to /e/ after a consonant or /s/ after a vowel.

- The 2nd and 3rd person plural verb subject suffixes, written /-id/ and /-ænd/ respectively, are pronounced [-in] and [-æn].

- Many frequently-occurring verbs are shortened, such as میخواهم /mixɒːhæm/ михоҳам ('I want') → [mixɒːm], and میروم /miɾævæm/ меравам ('I go'_ → [miɾæm].

Example

| Broad IPA Transcription | Perso-Arabic script | Cyrillic script | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| /jek ˈɾuz ˈbɒde ʃoˈmɒlo xorˈʃid bɒhæm dæʔˈvɒ ˈmikæɾdænd ke koˈdɒm jek ɢæviˈtæɾ æst/[1] | یک روز باد شمال و خورشید با هم دعوا میکردند که کدام یک قویتر است | Як руз боди шумал у хуршед бо ҳам даъво микарданд ки кудом як қавитар аст. | [One day] the North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger. |

References

- 1 2 International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-521-63751-0.

- ↑ Campbell, George L. (1995). "Persian". Concise compendium of the world's languages (1st publ. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 385. ISBN 0415160499.

- 1 2 Toosarvandani, Maziar D. 2004 "Vowel Length in Modern Farsi", JRAS, Series 3, 14, 3, pp. 241–251.

- 1 2 3 4 Windfuhr, Gernot L. (1979). Persian grammar: History and State of its Study. Mouton. p. 137. ISBN 9027977747.

- 1 2 3 Alamolhoda, Seyyed Morleza (2000). "Phonostatistics and Phonotactics of the Syllable in Modern Persian". Studia Orientalia. 89: 14–15. ISSN 0039-3282.

- ↑ Rees, Daniel A. (2008). "From Middle Persian to Proto-Modern Persian". Towards Proto-Persian: An Optimality Theoretic Historical Reconstruction (Ph.D.).

- ↑ Windfuhr, Gernot (1987). "Persian". In Bernard Comrie. The World's Major Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 543. ISBN 978-0-19-506511-4.

- 1 2 3 Mahootian, Shahrzad (1997). Persian. London: Routledge. pp. 287, 292, 303, 305. ISBN 0-415-02311-4.

- ↑ Mace, John (March 1993). Modern Persian. Teach Yourself. ISBN 0-8442-3815-5.

- ↑ Vrzić, Zvjezdana (2007), Farsi: A Complete Course for Beginners, Living Language, Random House, p. xxiii, ISBN 978-1-4000-2347-9

- ↑ Jahani, Carina (2005). "The Glottal Plosive: A Phoneme in Spoken Modern Persian or Not?". In Éva Ágnes Csató; Bo Isaksson; Carina Jahani. Linguistic Convergence and Areal Diffusion: Case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 79–96. ISBN 0-415-30804-6.

- ↑ Windfuhr, Gernot L. 1997. . In Kaye, Alan S. / Daniels, Peter T. (eds). Phonologies of Asia and Africa (including the Caucasus), I-II, pp.675-689. Winona Lake, Eisenbrauns.

- ↑ Abolhasanizadeh, Vahideh, Mahmood Bijankhan, & Carlos Gussenhoven, 2012. "The Persian pitch accent and its retention after the focus", Lingua 122, 13.

- 1 2 3 Sadat-Tehrani, Nima, 2007. "The Intonational Grammar of Persian". Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manitoba, pp.3, 22, 46-47, 51.

- 1 2 Hosseini, Seyed Ayat 2014 "The Phonology and Phonetics of Prosodic Prominence in Persian" Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Tokyo, p.22f for a review of the literature; also p.35.

- 1 2 Mace, John (2003). Persian Grammar: For reference and revision. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1695-5.

- ↑ Thackston, W. M. (1993-05-01). "Colloquial Transformations". An Introduction to Persian (3rd Rev ed.). Ibex Publishers. pp. 205–214. ISBN 0-936347-29-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iranian Persian pronunciation. |