Persephone

| Persephone | |

|---|---|

| Goddess of the underworld, springtime, flowers, vegetation | |

| |

| Abode | The Underworld, Sicily, Mount Olympus |

| Symbol | Pomegranate, Seeds of Grain, Torch, Flowers, Deer |

| Consort | Hades |

| Parents | Zeus and Demeter |

| Siblings | Aeacus, Amphitheus I, Angelos, Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Arion, Artemis, Athena, Chrysothemis, Despoina, Dionysus, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Eubuleus, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Philomelus, Plutus, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Children | Melinoe, Zagreus |

| Roman equivalent | Proserpina |

| Part of a series on | ||||||

| Ancient Greek religion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

Godheads

|

||||||

|

Ethics |

||||||

|

Practices |

||||||

|

| ||||||

In Greek mythology, Persephone (/pərˈsɛfəni/, per-SEH-fə-nee; Greek: Περσεφόνη), also called Kore or Cora (/ˈkɔəriː/; "the maiden"),[n 1] is the daughter of Zeus and the harvest goddess Demeter, and is the queen of the underworld. Homer describes her as the formidable, venerable majestic princess of the underworld, who carries into effect the curses of men upon the souls of the dead. Persephone was married to Hades, the god-king of the underworld.[1] The myth of her abduction represents her function as the personification of vegetation, which shoots forth in spring and withdraws into the earth after harvest; hence, she is also associated with spring as well as the fertility of vegetation. Similar myths appear in the Orient, in the cults of male gods like Attis, Adonis and Osiris,[2] and in Minoan Crete.

Persephone as a vegetation goddess and her mother Demeter were the central figures of the Eleusinian mysteries that predated the Olympian pantheon and promised the initiated a more enjoyable prospect after death. Persephone is further said to have become by Zeus the mother of Dionysus, Iacchus, or Zagreus, usually in orphic tradition.[3] The origins of her cult are uncertain, but it was based on very old agrarian cults of agricultural communities.

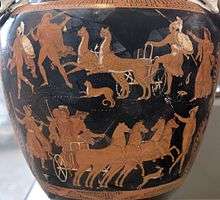

Persephone was commonly worshipped along with Demeter and with the same mysteries. To her alone were dedicated the mysteries celebrated at Athens in the month of Anthesterion. In Classical Greek art, Persephone is invariably portrayed robed, often carrying a sheaf of grain. She may appear as a mystical divinity with a sceptre and a little box, but she was mostly represented in the process of being carried off by Hades.

In Roman mythology, she is called Proserpina, and her mother, Ceres.

Name

Etymology

In a Linear B (Mycenean Greek) inscription on a tablet found at Pylos dated 1400–1200 BC, John Chadwick reconstructed[n 2] the name of a goddess *Preswa who could be identified with Persa, daughter of Oceanus and found speculative the further identification with the first element of Persephone.[5] Persephonē (Greek: Περσεφόνη) is her name in the Ionic Greek of epic literature. The Homeric form of her name is Persephoneia (Περσεφονεία,[6] Persephoneia). In other dialects she was known under variant names: Persephassa (Περσεφάσσα), Persephatta (Περσεφάττα), or simply Korē (Κόρη, "girl, maiden").[7] Plato calls her Pherepapha (Φερέπαφα) in his Cratylus, "because she is wise and touches that which is in motion". There are also the forms Periphona (Πηριφόνα) and Phersephassa (Φερσέφασσα). The existence of so many different forms shows how difficult it was for the Greeks to pronounce the word in their own language and suggests that the name may have a Pre-Greek origin.[8]

Persephatta (Περσεφάττα) is considered to mean "female thresher of grain," going by "perso-" relating to Sanskrit "parsa", "sheaf of grain" and the second constituent of the name originating in Proto-Indo European *-gʷʰn-t-ih, from the root *gʷʰen "to strike".[9]

An alternative etymology is from φέρειν φόνον, pherein phonon, "to bring (or cause) death".[10]

John Chadwick speculatively relates the name of Persephone with the name of Perse, daughter of Oceanus.[11]

Roman Proserpina

The Romans first heard of her from the Aeolian and Dorian cities of Magna Graecia, who used the dialectal variant Proserpinē (Προσερπίνη). Hence, in Roman mythology she was called Proserpina, a name erroneously derived by the Romans from proserpere, "to shoot forth"[12] and as such became an emblematic figure of the Renaissance.

At Locri, perhaps uniquely, Persephone was the protector of marriage, a role usually assumed by Hera; in the iconography of votive plaques at Locri, her abduction and marriage to Hades served as an emblem of the marital state, children at Locri were dedicated to Proserpina, and maidens about to be wed brought their peplos to be blessed.[13]

Nestis

In a Classical period text ascribed to Empedocles, c. 490 – 430 BC,[n 3] describing a correspondence among four deities and the classical elements, the name Nestis for water apparently refers to Persephone: "Now hear the fourfold roots of everything: enlivening Hera, Hades, shining Zeus. And Nestis, moistening mortal springs with tears."[14]

Of the four deities of Empedocles' elements, it is the name of Persephone alone that is taboo—Nestis is a euphemistic cult title[n 4]—for she was also the terrible Queen of the Dead, whose name was not safe to speak aloud, who was euphemistically named simply as Kore or "the Maiden", a vestige of her archaic role as the deity ruling the underworld.

Titles and functions

The epithets of Persephone reveal her double function as chthonic and vegetation goddess. The surnames given to her by the poets refer to her character as Queen of the lower world and the dead, or her symbolic meaning of the power that shoots forth and withdraws into the earth. Her common name as a vegetation goddess is Kore and in Arcadia she was worshipped under the title Despoina "the mistress", a very old chthonic divinity. Plutarch identifies her with spring and Cicero calls her the seed of the fruits of the fields. In the Eleusinian mysteries her return is the symbol of immortality and hence she was frequently represented on sarcophagi.[10]

In the mystical theories of the Orphics and the Platonists, Kore is described as the all-pervading goddess of nature[15] who both produces and destroys everything and she is therefore mentioned along or identified with other mystic divinities such as Isis, Rhea, Ge, Hestia, Pandora, Artemis, and Hecate.[16] The Orphic Persephone is further said to have become by Zeus the mother of Dionysus, Iacchus, Zagreus,[10] and the little-attested Melinoe.[17]

Epithets

As a goddess of the underworld, Persephone was given euphemistically friendly names.[18] However it is possible that some of them were the names of original goddesses:

- Despoina (dems-potnia) "the mistress" (literally "the mistress of the house") in Arcadia.

- Hagne, "pure", originally a goddess of the springs in Messenia.[19]

- Melindia or Melinoia (meli, "honey"), as the consort of Hades, in Hermione. (Compare Hecate, Melinoe)[18]

- Melivia[18]

- Melitodes[18]

- Aristi cthonia, "the best chthonic".[18]

- Praxidike, the Orphic Hymn to Persephone identifies Praxidike as an epithet of Persephone: "Praxidike, subterranean queen. The Eumenides' source [mother], fair-haired, whose frame proceeds from Zeus' ineffable and secret seeds."[20][21]

As a vegetation goddess she was called:[19][22]

- Kore, "the maiden".

- Kore Soteira, "the savior maiden" in Megalopolis.

- Neotera, "the younger " in Eleusis.

- Kore of Demeter Hagne, in the Homeric hymn.

- Kore memagmeni, "the mixed daughter" (bread).

Demeter and her daughter Persephone were usually called:[22][23]

- The goddesses, often distinguished as "the older" and "the younger" in Eleusis.

- Demeters, in Rhodes and Sparta

- The thesmophoroi, "the legislators" in the Thesmophoria.

- The Great Goddesses, in Arcadia.

- The mistresses in Arcadia.[24]

- Karpophoroi, "the bringers of fruit", in Tegea of Arcadia.

Origins of the cult

The myth of the abduction of the vegetation goddess is Pre-Greek as evident in the Syro-Mesopotamian mythology of the abduction of the goddess of fertility and harvest, Ishtar (also Ashtar, Astarte and Inanna). The place of the abduction is different in each local cult. The Homeric Hymn to Demeter mentions the "plain of Nysa".[25] The locations of this probably mythical place may simply be conventions to show that a magically distant chthonic land of myth was intended in the remote past.[26][27] Demeter found and met her daughter in Eleusis, and this is the mythical disguise of what happened in the mysteries.[28]

Persephone is an old chthonic deity of the agricultural communities, who received the souls of the dead into the earth, and acquired powers over the fertility of the soil, over which she reigned. The earliest depiction of a goddess who may be identified with Persephone growing out of the ground, is on a plate from the Old-Palace period in Phaistos. The goddess has a vegetable-like appearance, and she is surrounded by dancing girls between blossoming flowers.[29][30] A similar representation, where the goddess appears to come down from the sky, is depicted on the Minoan ring of Isopata.

In some forms Hades appears with his chthonic horses. The myth of the rape of Kore was derived from the idea that Hades catches the souls of the dead like his booty, and then carries them with his horses into his kingdom. This idea is vague in Homer, but appears in later Greek depictions, and in Greek folklore. "Charos" appears with his horse and carries the dead into the underworld.[31][32]

The cults of Persephone and Demeter in the Eleusinian mysteries and in the Thesmophoria were based on very old agrarian cults. An earlier agrarian procession led by a priest, is depicted on a Minoan vase from the end of the New Palace Period.[33] Ancient cults like age-old cults of the dead, with worship of animal-headed gods and rituals for the new crop, had their position in Greek religion because they were connected with daily or seasonal tasks and consecrated by immemorial practices. The powers of animal nature fostered a belief in nymphs, and in gods with human forms and the heads or tails of animals. In the Arcadian cults, it seems that Demeter and Persephone were the first of a series of daemons with the same nature.

A lot of ancient beliefs were based on initiation into jealously-guarded mysteries (secret rites) because they offered prospects after death more enjoyable than the final end at the gloomy space of the Greek Hades. It seems that such religious practices were introduced from Minoan Crete,[34][35] Similar practices appear also in the Near East. However, the idea of immortality which appears in the syncretistic religions of the Near East did not exist in the Eleusinian mysteries at the very beginning.[36][37]

Near East - Minoan Crete

In the Near eastern myth of the primitive agricultural societies, every year the fertility goddess bore the "god of the new year", who then became her lover, and died immediately in order to be reborn and face the same destiny. Some findings from Catal Huyuk since the Neolithic age, indicate the worship of the Great Goddess accompanied by a boyish consort, who symbolizes the annual decay and return of vegetation.[38] Similar cults of resurrected gods appear in the Near East and Egypt in the cults of Attis, Adonis and Osiris,[39] In Minoan Crete, the "divine child" was related to the female vegetation divinity Ariadne who died every year.[40] The Minoan religion had its own characteristics. The cult was aniconic, the principal deities were female, and they appeared in epiphany called chiefly by ecstatic sacral dances, by tree–shaking and by baetylic rites.[41]

The daemons were a part of the religious system. They were considered divine, and they were connected with gods or goddesses of hunting. In the Minoan seals or jewellery, are depicted animal-headed daemons[42] or hybrid creatures. Some of these depictions seem similar to Near Eastern depictions, especially with the well known Babylonian daemons. A young Minotaur is depicted on a seal from Knossos.[43] Depictions of daemons between lions, of men between daemons, and processions of daemons, appear also on Mycenean seals and jewellery, and in Phigalia of Arcadia.[44]

The most peculiar feature of the Minoan belief in the divine, is the appearance of the goddess from above in the dance. Dance floors have been discovered in addition to "vaulted tombs", and it seems that the dance was ecstatic. Homer memorializes the dance floor which Daedalus built for Ariadne in the remote past.[45] On the gold ring from Isopata, four women in festal attire are performing a dance between blossoming flowers. Above a figure apparently floating in the air seems to be the goddess herself, appearing amid the whirling dance.[46] An image plate from the first palace of Phaistos, seems to be very close to the mythical image of the Anodos (ascent) of Persephone. Two girls dance between blossoming flowers, on each side of a similar but armless and legless figure which seems to grow out of the ground. The goddess is bordered by snake lines which give her a vegetable like appearance and also recall the arrangement of snake tubes which have been found in Minoan and Mycenean sanctuaries. She has a large stylized flower turned over her head, and the resemblance with the flower-picking Persephone and her companions is compelling.[29] The depiction of the goddess is similar to later images of "Anodos of Pherephata". On the Dresden vase, Persephone is growing out of the ground, and she is surrounded by the animal-tailed agricultural gods Silenoi.[47] It seems that in Crete there were festivals designated in a way corresponding to the later Greek types of festival names.[29] An agrarian procession is depicted on the "Harvesters Vase" or "Vase of the Winnowers" from the last phase of the New Palace Period (LM II), which was found in Hagia Triada. Men are walking two by two with their tool-rods on their shoulders. The leader is probably a priest with long hair carrying a stick, and dressed in a priestly robe with a fringe. A group of musicians participate singing, and one of them holds an Egyptian sistrum.[33][48]

The Minoan vegetation goddess Ariadne was closely connected with the cult of the divine child, and with the "cult of the tree". This was an ecstatic and orgiastic cult, which seems to be similar to its relative in the Syrian cult of Adonis,.[49] Kerenyi suggests that the name Ariadne (derived from ἁγνή, hagne, "pure"), was an euphemistical name given by the Greeks to the nameless "Mistress of the labyrinth" who appears in a Mycenean Greek inscription from Knossos in Crete. The Greeks used to give friendly names to the deities of the underworld. Cthonic Zeus was called Eubuleus, "the good counselor", and the ferryman of the river of the underworld Charon, "glad".[32] Despoina and "Hagne" were probably euphemistic surnames of Persephone, therefore he theorizes that the cult of Persephone was the continuation of the worship of a Minoan Great goddess. The labyrinth was both a winding dance-ground and, in the Greek view, a prison with the dreaded Minotaur at its centre.[50][51] It is possible that some religious practices, especially the mysteries, were transferred from a Cretan priesthood to Eleusis, where Demeter brought the poppy from Crete.[52] Besides these similarities, Burkert explains that up to now it is not known to what extent one can and must differentiate between Minoan and Mycenean religion.[53] It seems that the Minoan vegetation goddess Ariadne was absorbed by more powerful divinities.[54] She survived in Greek folklore as the consort of Dionysos, with whom she was worshiped in some local cults. In the Anthesteria Dionysos is the "divine child".

In historical times the Minoan "cult of the tree", was almost forgotten. It existed in some local cults like the cult of the vegetation goddess Helena Dendritēs (dendron, "tree") in Rhodes, and a cult of Artemis in the Peloponnese. In this cult, Artemis is hanged from a tree, just like Ariadne in Greek mythology, who was hanged from a tree when she was abandoned by Theseus.[55]

Mycenean Greece

It seems that the Greek deities began their career as powers of nature, but then they were given other functions and attributes by their worshippers.[54] The powers of animal nature fostered a belief in nymphs, whose existence was bound to the trees or the waters which they haunted, and in gods with human forms and the heads or tails of animals. The ancient gods with tails of animals who stood for primitive bodily instincts, were considered to protect the flocks and herds, and some of them survived in the cult of Dionysos (Satyrs and Seilinoi) and Pan (the goat-god). Such figures were believed to give help to men who watched over crops and herds, and later they were below the Olympians.[56]

There is evidence of a cult in Eleusis from the Mycenean period,[57] however, there are not sacral finds from this period. The cult was private and there is no information about it. As well as the names of some Greek gods in the Mycenean Greek inscriptions, also appear names of goddesses, like "the divine Mother" (the mother of the gods) or "the Goddess (or priestess) of the winds", who don't have Mycenean origin.[28] In historical times Demeter and Kore were usually referred to as "the goddesses" or "the mistresses" (Arcadia) in the mysteries.[58] In the Mycenean Greek tablets dated 1400–1200 BC, the "two mistresses (potniai) and the king" are mentioned. John Chadwick believes that these were the precursor divinities of Demeter, Persephone and Poseidon.[59]

Persephone was conflated with Despoina, "the mistress", a chthonic divinity in West-Arcadia.[35] The megaron of Eleusis, is quite similar with the "megaron" of Despoina at Lycosura.[28] The names Demeter and Kore are Greek, and this probably indicates that the Greeks adopted these divinities during their wandering, and that they were later fused with local divinities in the ancient cults.[60] The Arcadian cults come from a more primitive religion, and evidently the religious beliefs of the first Greek-speaking people who entered the region, were mixed with the beliefs of the indigenous population. Most of the temples were built near springs, and in some of them there is evidence of the existence of a fire, which was always burning. At Lycosura, a fire was burning in front of the temple of Pan (the goat-god).[23] In Eleusis, in a ritual, one child ("pais") was initiated from the hearth. The name pais (the divine child) appears in the Mycenean inscriptions.,[28] and the ritual indicates the transition from the old funerary practices to the Greek cremation.[61]

The two goddesses, were closely related with the springs and the animals. At Lycosura on a marble relief on the veil of Despoina appear figures with the heads of different animals obviously in a ritual dance, and some of them hold a flute. These could be hybrid creatures or a procession of women with animal-masks.[62] Similar processions of daemons, or human figures with animal-masks appear on Mycenean frescoes and gold rings.[63][64] It seems that Demeter and Kore, were the first of a series of daemons with the same nature, just as Artemis was the first of the nymphs.[23]

Demeter and Persephone, were the two Great Goddesses of the Arcadian mysteries. Despoine was one of her surnames just as the surname of Persephone Kore.[65] Her name was not allowed to be revealed to the uninitiated, and she was daughter of Demeter, who was united with the god of the storms and rivers Poseidon Hippios (horse).[66] In northern European folklore, the river spirit of the underworld appears frequently as a horse. The union of the fertility goddess with the beast which represents the masculine fertility, is an old Near Eastern myth, which appears in many primitive agricultural societies. The ritual copulation in Minoan Crete was related to moon-goddesses like Europa and Pasiphae, but this cult was almost forgotten by the Greeks. It survived in the myths of the hybrid creature Minotaur, and of the abduction of the Phoenician princess Europa by the white bull (Zeus).[40] The animal-headed gods were depicted in the local cults of isolated Arcadia, or in Crete in the depiction of the dog-headed Hecate.[67] The animal masks were substituted by masks representing human faces, as it appears in the temple of Artemis Orthia at Sparta. Dancing girls used these masks during the annual "vegetation ritual ".[68]

The Minoan "cult of the tree" appears also in Mycenean seals and jewellery, however, it is not known if this cult in Greece was similar with the Minoan. Later the cult of Dionysos was closely associated with trees, specifically the fig tree, and some of his bynames exhibit this, such as Endendros or Dendritēs (dendron, "tree").[69] According to Pherecydes of Syros, the second element of his name is derived from nũsa, an archaic word for "tree".[70] It is possible that the meaning of tree was re-interpreted to the name of the mountain Nysa, the birthplace of Dionysos, according to the axis mundi of Indo-European mythology .[71] In Greek mythology Nysa is a mythical mountain with an unknown location.[27] Nysion (or Mysion), the place of the abduction of Persephone was also probably a mythical place which did not exist on the map, a magically distant chthonic land of myth which was intended in the remote past.[22] An image plate from the first palace of Phaistos, seems to be very close to the mythical image of the Anodos (ascent) of Persephone. Two girls dance on each side of a similar but armless and legless figure which seems to grow out of the ground. She has a large stylized flower turned over her head.[29] The depiction of the goddess is similar with later images of "Anodos of Pherephata". On the Dresden vase Persephone is growing out of the ground, and she is surrounded by the animal-tailed agricultural gods Silenoi.[47]

It seems that in Crete there were festivals designated in a way corresponding to the later Greek types of festival names.[29] An agrarian procession is depicted on the "Harvesters Vase" or "Vase of the Winnowers" from the last phase of the New Palace Period (LM II), which was found in Hagia Triada. Men are walking two by two with their tool-rods on their shoulders. The leader is probably a priest with long hair carrying a stick, and dressed in a priestly robe with a fringe. A group of musicians participate singing, and one of them holds an Egyptian sistrum.[33][48]

Greek mythology

Abduction myth

Persephone used to live far away from the other gods, a goddess within Nature herself before the days of planting seeds and nurturing plants. In the Olympian telling, the gods Hermes and Apollo had wooed Persephone; but Demeter rejected all their gifts and hid her daughter away from the company of the Olympian gods.[72] The story of her abduction by Hades against her will is traditionally referred to as the Rape of Persephone. It is mentioned briefly in Hesiod's Theogony,[73] and told in considerable detail in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. Zeus, it is said, permitted Hades, who was in love with the beautiful Persephone, to carry her off as her mother Demeter was not likely to allow her daughter to go down to Hades. Persephone was gathering flowers with the Oceanids along with Artemis and Athena—the Homeric Hymn says—in a field when Hades came to abduct her, bursting through a cleft in the earth.[74] Demeter, when she found her daughter had disappeared, searched for her all over the earth with Hecate's torches. In most versions she forbids the earth to produce, or she neglects the earth and in the depth of her despair she causes nothing to grow. Helios, the sun, who sees everything, eventually told Demeter what had happened and at length she discovered the place of her abode. Finally, Zeus, pressed by the cries of the hungry people and by the other deities who also heard their anguish, forced Hades to return Persephone.[75]

Hades indeed complied with the request, but first he tricked her, giving her some pomegranate seeds to eat. Persephone was released by Hermes, who had been sent to retrieve her, but because she had tasted food in the underworld, she was obliged to spend a third of each year (the winter months) there, and the remaining part of the year with the gods above.[76] With the later writers Ovid and Hyginus, Persephone's time in the underworld becomes half the year.[77]

Various local traditions place Persephone's abduction in a different location. The Sicilians, among whom her worship was probably introduced by the Corinthian and Megarian colonists, believed that Hades found her in the meadows near Enna, and that a well arose on the spot where he descended with her into the lower world. The Cretans thought that their own island had been the scene of the rape, and the Eleusinians mentioned the Nysian plain in Boeotia, and said that Persephone had descended with Hades into the lower world at the entrance of the western Oceanus. Later accounts place the rape in Attica, near Athens, or near Eleusis.[75]

.jpg)

The Homeric hymn mentions the Nysion (or Mysion) which was probably a mythical place. The location of this mythical place may simply be a convention to show that a magically distant chthonic land of myth was intended in the remote past.[22] Before Persephone was abducted by Hades, the shepherd Eumolpus and the swineherd Eubuleus saw a girl in a black chariot driven by an invisible driver being carried off into the earth which had violently opened up. Eubuleus was feeding his pigs at the opening to the underworld when Persephone was abducted by Plouton. His swine were swallowed by the earth along with her, and the myth is an etiology for the relation of pigs with the ancient rites in Thesmophoria,[78] and in Eleusis.

In the hymn, Persephone returns and she is reunited with her mother near Eleusis. Demeter as she has been promised established her mysteries (orgies) when the Eleusinians built for her a temple near the spring of Callichorus. These were awful mysteries which were not allowed to be uttered. The uninitiated would spend a miserable existence in the gloomy space of Hades after death.[n 5]

In some versions, Ascalaphus informed the other deities that Persephone had eaten the pomegranate seeds. When Demeter and her daughter were reunited, the Earth flourished with vegetation and color, but for some months each year, when Persephone returned to the underworld, the earth once again became a barren realm. This is an origin story to explain the seasons.

In an earlier version, Hecate rescued Persephone. On an Attic red-figured bell krater of c. 440 BC in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Persephone is rising as if up stairs from a cleft in the earth, while Hermes stands aside; Hecate, holding two torches, looks back as she leads her to the enthroned Demeter.[79]

The 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia Suda introduces a goddess of a blessed afterlife assured to Orphic mystery initiates. This Macaria is asserted to be the daughter of Hades, but no mother is mentioned.[80]

Interpretation of the myth

In the myth Pluto abducts Persephone to be his wife and the queen of his realm.[81] Pluto (Πλούτων, Ploutōn) was a name for the ruler of the underworld; the god was also known as Hades, a name for the underworld itself. The name Pluton was conflated with that of Ploutos (Πλούτος Ploutos, "wealth"), a god of wealth, because mineral wealth was found underground, and because Pluto as a chthonic god ruled the deep earth that contained the seeds necessary for a bountiful harvest.[82] Plouton is lord of the dead, but as Persephone's husband he has serious claims to the powers of fertility.[83]

In the Theogony of Hesiod, Demeter was united with the hero Iasion in Crete and she bore Ploutos.[73] This union seems to be a reference to a hieros gamos (ritual copulation) to ensure the earth's fertility.[83] This ritual copulation appears in Minoan Crete, in many Near Eastern agricultural societies, and also in the Anthesteria.[n 6]

Nilsson believes that the original cult of Ploutos (or Pluto) in Eleusis was similar with the Minoan cult of the "divine child", who died in order to be reborn. The child was abandoned by his mother and then it was brought up by the powers of nature. Similar myths appear in the cults of Hyakinthos (Amyklai), Erichthonios (Athens), and later in the cult of Dionysos.[85]

The Greek version of the abduction myth is related to grain – important and rare in the Greek environment – and the return (ascent) of Persephone was celebrated at the autumn sowing. Pluto (Ploutos) represents the wealth of the grain that was stored in underground silos or ceramic jars (pithoi), during summer months. Similar subterranean pithoi were used in ancient times for burials and Pluto is fused with Hades, the King of the realm of the dead. During summer months, the Greek grain-Maiden (Kore) is lying in the grain of the underground silos, in the realm of Hades and she is fused with Persephone, the Queen of the underworld. At the beginning of the autumn, when the seeds of the old crop are laid on the fields, she ascends and is reunited with her mother Demeter, for at that time the old crop and the new meet each other. For the initiated, this union was the symbol of the eternity of human life that flows from the generations which spring from each other.[86][87]

Arcadian myths

The primitive myths of isolated Arcadia seem to be related to the first Greek-speaking people who came from the north-east during the bronze age. Despoina (the mistress), the goddess of the Arcadian mysteries, is the daughter of Demeter and Poseidon Hippios (horse), who represents the river spirit of the underworld that appears as a horse as often happens in northern-European folklore. He pursues the mare-Demeter and from the union she bears the horse Arion and a daughter who originally had the form or the shape of a mare. The two goddesses were not clearly separated and they were closely connected with the springs and the animals. They were related with the god of rivers and springs; Poseidon and especially with Artemis, the Mistress of the Animals who was the first nymph.[1] According to the Greek tradition a hunt-goddess preceded the harvest goddess.[88] In Arcadia, Demeter and Persephone were often called Despoinai (Δέσποιναι, "the mistresses") in historical times. They are the two Great Goddesses of the Arcadian cults, and evidently they come from a more primitive religion.[22] The Greek god Poseidon probably substituted the companion (Paredros, Πάρεδρος) of the Minoan Great goddess[89] in the Arcadian mysteries.

Queen of the Underworld

Persephone held an ancient role as the dread queen of the Underworld, within which tradition it was forbidden to speak her name. This tradition comes from her conflation with the very old chthonic divinity Despoina (the mistress), whose real name could not be revealed to anyone except those initiated to her mysteries.[66] As goddess of death she was also called a daughter of Zeus and Styx,[90] the river that formed the boundary between Earth and the underworld. Homer describes her as the formidable, venerable majestic queen of the shades, who carries into effect the curses of men upon the souls of the dead, along with her husband Hades.[91] In the reformulation of Greek mythology expressed in the Orphic Hymns, Dionysus and Melinoe are separately called children of Zeus and Persephone.[92] Groves sacred to her stood at the western extremity of the earth on the frontiers of the lower world, which itself was called "house of Persephone".[93]

Her central myth served as the context for the secret rites of regeneration at Eleusis,[94] which promised immortality to initiates.

Cult of Persephone

Persephone was worshipped along with her mother Demeter and in the same mysteries. Her cults included agrarian magic, dancing, and rituals. The priests used special vessels and holy symbols, and the people participated with rhymes. In Eleusis there is evidence of sacred laws and other inscriptions.[95]

The Cult of Demeter and the Maiden is found at Attica, in the main festivals Thesmophoria and Eleusinian mysteries and in a lot of local cults. These festivals were almost always celebrated at the autumn sowing, and at full-moon according to the Greek tradition. In some local cults the feasts were dedicated to Demeter.

Thesmophoria

Thesmophoria, were celebrated in Athens, and the festival was widely spread in Greece. This was a festival of secret women-only rituals connected with marriage customs and commemorated the third of the year, in the month Pyanepsion, when Kore was abducted and Demeter abstained from her role as goddess of harvest and growth. The ceremony involved sinking sacrifices into the earth by night and retrieving the decaying remains of pigs that had been placed in the megara of Demeter (trenches and pits or natural clefts in rock), the previous year. These were placed on altars, mixed with seeds, then planted.[96] Pits rich in organic matter at Eleusis have been taken as evidence that the Thesmophoria was held there as well as in other demes of Attica.[97] This agrarian magic was also used in the cult of the earth-goddesses potniai (mistresses) in the Cabeirian, and in Knidos.[98]

The festival was celebrated over three days. The first was the "way up" to the sacred space, the second, the day of feasting when they ate pomegranate seeds and the third was a meat feast in celebration of Kalligeneia a goddess of beautiful birth. Zeus penetrated the mysteries as Zeus- Eubuleus[96] which is an euphemistical name of Hades (Chthonios Zeus).[18] In the original myth which is an etiology for the ancient rites, Eubuleus was a swineherd who was feeding his pigs at the opening to the underworld when Persephone was abducted by Plouton. His swine were swallowed by the earth along with her.[78]

Eleusinian mysteries

The Eleusinian mysteries was a festival celebrated at the autumn sowing in the city of Eleusis. Inscriptions refer to "the Goddesses" accompanied by the agricultural god Triptolemos (probably son of Ge and Oceanus),[99] and "the God and the Goddess" (Persephone and Plouton) accompanied by Eubuleus who probably led the way back from the underworld.[100] The myth was represented in a cycle with three phases: the "descent", the "search", and the "ascent", with contrasted emotions from sorrow to joy which roused the mystae to exultation. The main theme was the ascent of Persephone and the reunion with her mother Demeter.[86] The festival activities included dancing, probably across the Rharian field, where according to the myth the first grain grew.

At the beginning of the feast, the priests filled two special vessels and poured them out, the one towards the west, and the other towards the east. The people looking both to the sky and the earth shouted in a magical rhyme "rain and conceive". In a ritual, a child was initiated from the hearth (the divine fire). It was the ritual of the "divine child" who originally was Ploutos. In the Homeric hymn the ritual is connected with the myth of the agricultural god Triptolemos[61] The high point of the celebration was "an ear of grain cut in silence", which represented the force of the new life. The idea of immortality didn't exist in the mysteries at the beginning, but the initiated believed that they would have a better fate in the underworld. Death remained a reality, but at the same time a new beginning like the plant which grows from the buried seed.[28] In the earliest depictions Persephone is an armless and legless deity, who grows out of the ground.[101]

Local cults

_(12853680765).jpg)

Local cults of Demeter and Kore existed in Greece, Asia Minor, Sicily, Magna Graecia, and Libya.

- Attica:[102]

- Athens, in the mysteries of Agrae. This was a local cult near the river Ilissos. They were celebrated during spring in the month Anthesterion. Later they became an obligation for the participants of the “greater” Eleusinian mysteries. There was a temple of Demeter and Kore, and an image of Triptolemos.[103]

- Piraeus: The Skirophoria, a festival related to the Thesmophoria.

- Megara: Cult of Demeter thesmophoros and Kore. The city was named after its megara .[104]

- Aegina: Cult of Demeter thesmophoros and Kore.

- Phlya, near Koropi, in the mysteries of Phlya: These have very old roots, and were probably originally dedicated to Demeter Anesidora, Kore, and Zeus- Ktesios, who was the god of the underground stored grain. Pausanias mentions a temple of Demeter-Anesidora, Kore Protogone, and Zeus Ktesios. The surname Protogonos, indicates a later Orphic influence. It seems that the mysteries were related to the mysteries of Andania in Messene.[105]

- Boeotia:

- Thebes, which Zeus is said to have given to her as an acknowledgement for a favour she had bestowed upon him.[106] Pausanias records a grove of Cabeirian Demeter and the Maid, three miles outside the gates of Thebes, where a ritual was performed, so-called on the grounds that Demeter gave it to the Cabeiri, who established it at Thebes. The Thebans told Pausanias that some inhabitants of Naupactus had performed the same rituals there, and had met with divine vengeance.[107] The Cabeirian mysteries were introduced from Asia Minor at the end of the archaic period. Nothing is known of the older cult, and it seems that the Cabeiri were originally wine-daemons. Inscriptions from the temple in Thebes mention the old one as Cabir, and the new one as son (pais), who are different.[105] According to Pausanias, Pelarge, the daughter of Potnieus, was connected with the cult of Demeter in the Cabeirian (potniai).[98]

- A feast in Boeotia, in the month Demetrios (Pyanepsion), probably similar with the Thesmophoria.

- Thebes: Cult of Demeter and Kore in a feast named Thesmophoria but probably different. It was celebrated in the summer month Bukatios.[22][108]

- Peloponnese (except Arcadia)[22]

- Hermione: An old cult of Demeter Chthonia, Kore, and Klymenos (Hades). Cows were pushed into the temple, and then they were killed by four women. It is possible that Hermione was a mythical name, the place of the souls.[18]

- Asine: Cult of Demeter Chthonia. The cult seems to be related to the original cult of Demeter in Hermione.[18]

- Lakonia: Temple of Demeter Eleusinia near Taygetos. The feast was named Eleuhinia, and the name was given before the relation of Demeter with the cult of Eleusis.

- Lakonia at Aigila: Dedicated to Demeter. Men were excluded.

- near Sparta: Cult of Demeter and Kore, the Demeters (Δαμάτερες, "Damaters"). According to Hesychius, the feast lasted three days (Thesmophoria).

- Corinth: Cult of Demeter, Kore and Pluton.[18]

- Triphylia in Elis: Cult of Demeter, Kore and Hades.[18]

- Pellene: Dedicated to the Mysian Demeter. Men were excluded. The next day, men and women became naked.

- Andania in Messenia (near the borders of Arcadia): Cult of the Great goddesses, Demeter and Hagne. Hagne, a goddess of the spring, was the original deity before Demeter. The temple was built near a spring.

- Arcadia[23]

- Pheneos : Mysteries of Demeter Thesmia and Demeter Eleusinia. The Eleusinian cult was introduced later. The priest took the holy book from a natural cleft. He used the mask of Demeter Kidaria, and he hit his stick on the earth, in a kind of agrarian magic. An Arcadian dance was named kidaris.

- Pallantion near Tripoli: Cult of Demeter and Kore.

- Karyai: Cult of Kore and Pluton.[18]

- Tegea: Cult of Demeter and Kore, the Karpophoroi, "Fruit givers".

- Megalopolis: Cult of the Great goddesses, Demeter and Kore Sotira, "the savior ".

- Mantineia: Cult of Demeter and Kore in the fest Koragia.[109]

- Trapezus: Mysteries of the Great goddesses, Demeter and Kore. The temple was built near a spring, and a fire was burning out of the earth.

- near Thelpusa in Onkeion: Temple of Demeter Erinys (vengeful) and Demeter Lusia (bathing). In the myth Demeter was united with Poseidon Hippios (horse) and bore the horse Arion and the unnamed. The name Despoina was given in West Arcadia.

- Phigalia: Cult of the mare-headed Demeter (black), and Despoina. Demeter was depicted in her archaic form, a Medusa type with a horse's head with snaky hair, holding a dove and a dolphin.[110] The temple was built near a spring.

- Lycosura,Main article: DespoinaCult of Demeter and Despoina. In the portico of the temple of Despoina there was a tablet with the inscriptions of the mysteries. In front of the temple there was an altar to Demeter and another to Despoine, after which was one of the Great Mother. By the sides stood Artemis and Anytos, the Titan who brought up Despoine. Besides the temple, there was also a hall where the Arcadians celebrated the mysteries[111][112] A fire was always burning in front of the temple of Pan (the goat-god), the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks. In a relief appear dancing animal-headed women (or with animal-masks) in a procession. Near the temple have been found terracotta figures with human bodies, and heads of animals.[23]

- Islands

- Paros: Cult of Demeter, Kore and Zeus-Eubuleus.[18]

- Amorgos: Cult of Demeter, Kore and Zeus-Eubuleus.[18]

- Delos: Cult of Demeter, Kore, and Zeus-Eubuleus. Probably a different feast with the name Thesmophoria, celebrated in a summer month (the same month in Thebes). Two big loaves of bread were oferred to the two goddesses. Another feast was named Megalartia.[22][108]

- Mykonos: Cult of Demeter, Kore and Zeus-Buleus.

- Crete : Cult of Demeter and Kore, in the month Thesmophorios.

- Rhodes: Cult of Demeter and Kore, in the month Thesmophorios. The two goddesses are the Damaters in an inscription from Lindos

- Asia Minor

- Sicily

- Magna Graecia

- Epizephyrian Locri: A temple associated with childbirth; its treasure was looted by Pyrrhus.[115]

- Archaeological finds suggest that worship of Demeter and Persephone was widespread in Sicily and Greek Italy.

- Libya

Ancient literary references

- Homer:

- Iliad:

- "the gods fulfilled his curse, even Zeus of the nether world and dread Persephone." (9, line 457; A. T. Murray, trans)

- "Althea prayed instantly to the gods, being grieved for her brother's slaying; and furthermore instantly beat with her hands upon the all-nurturing earth, calling upon Hades and dread Persephone" (9, 569)

- Odyssey:

- "And come to the house of Hades and dread Persephoneia to seek sooth saying of the spirit of Theban Teiresias. To him even in death Persephoneia has granted reason that ..." (book 10, card 473)

- Iliad:

- Hymns to Demeter[116]

- Hymn 2:

- "Mistress Demeter goddess of heaven, which God or mortal man has rapt away Persephone and pierced with sorrow your dear heart?(hymn 2, card 40)

- Hymn 13:

- "I start to sing for Demeter the lovely-faced goddess, for her and her daughter the most beautiful Persephoneia. Hail goddess keep this city safe!" (hymn 13, card 1)

- Hymn 2:

- Pindar[116]

- Olympian:

- "Now go Echo, to the dark-walled home of Phersephona."(book O, poem 14)

- Isthmean:

- "Aecus showed them the way to the house of Phersephona and nymphs, one of them carrying a ball."(book 1, poem 8)

- Nemean:

- "Island which Zeus, the lord of Olympus gave to Phersephona;he nodded descent with his flowers hair."(book N, poem 1)

- Pythian:

- "You splendor-loving city, most beautiful on earth, home of Phersephona. You who inhabit the hill of well-built dwellings."(book P, poem 12)

- Olympian:

- Aeschylus[116]

- Libation bearers:

- Electra:"O Phersephassa, grant us indeed a glorious victory!" (card 479)

- Libation bearers:

- Aristophanes[116]

- Thesmophoriazusae:

- Mnesilochos:"Thou Mistress Demeter, the most valuable friend and thou Pherephatta, grant that I may be able to offer you!" (card 266)

- Thesmophoriazusae:

- Euripides[116]

- Alcestis:

- "O you brave and best hail, sitting as attendand Beside's Hades bride Phersephone!" (card 741)

- Hecuba:

- "It is said that any of the dead that stand beside Phersephone, that the Danaids have left the plains to Troy." (card 130)

- Alcestis:

- Bacchylides[116]

- Epinicians:

- "Flashing thunderbolt went down to the halls of slender-ankled Phersephona to bring up into the light of Hades." (book Ep. poem 5)

- Epinicians:

- Vergil[117]

- The Aeneid:

- "For since she had not died through fate, or by a well-earned death, but wretchedly, before her time, inflamed with sudden madness, Proserpine had not yet taken a lock of golden hair from her head, or condemned her soul to Stygian Orcus." (IV.696-99)

- The Aeneid:

Modern reception

In 1934, Igor Stravinsky based his melodrama Perséphone on Persephone's story. In 1961, Frederick Ashton of the Royal Ballet appropriated Stravinsky's score, to choreograph a ballet starring Svetlana Beriosova as Persephone.

Persephone also appears many times in popular culture. Featured in a variety of young adult novels such as "Persephone"[118] by Kaitlin Bevis, "Persephone's Orchard"[119] by Molly Ringle, "The Goddess Test" by Aimee Carter, "The Goddess Letters" by Carol Orlock, and "Abandon" by Meg Cabot, her story has also been treated by Suzanne Banay Santo in “Persephone Under the Earth" in the light of women's spirituality. Here Santo treats the mythic elements in terms of maternal sacrifice to the burgeoning sexuality of an adolescent daughter. Accompanied by the classic, sensual paintings of Frederic Lord Leighton and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Santo portrays Persephone not as a victim but as a woman in quest of sexual depth and power, transcending the role of daughter, though ultimately returning to it as an awakened Queen.[120]

See also

- Rape of Persephone

- Anthesphoria, festival honoring Proserpina, and Persephone

Notes and references

- Notes

- ↑ Cora, the Latinization of Kore, is not usually used anymore in modern English.

- ↑ The actual word in Linear B is 𐀟𐀩𐁚, pe-re-*82 or pe-re-swa; it is found on the PY Tn 316 tablet.[4]

- ↑ Empedocles was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher who was a citizen of Agrigentum, a Greek colony in Sicily.

- ↑ Kingsley 1995 identifies Nestis as a cult title of Persephone.

- ↑ Hom. Hymn. to Demeter 470:

"Awful mysteries which no one may in any way transgress or pry into or utter, for deep awe of the gods checks the voice. Happy is he among men upon earth who has seen these mysteries; but he who is uninitiate and who has no part in them, never has lot of like good things once he is dead, down in the darkness and gloom". - ↑ "This is the time when Zeus mated with Semele, who is also Persephone, and Dionysos was conceived. It is also the time when Dionysos took Ariadne to be His wife, and so we celebrate the marriage of the Basilinna (religious Queen) and the God". [84]

- References

- 1 2 Martin Nilsson (1967). Die Geschichte der Griechische Religion Vol I pp 462–463, 479–480

- ↑ Fraser. The golden bough. Adonis, Attis and Osiris. Martin Nilsson (1967). Vol I, pp. 215

- ↑ reference needed

- ↑ Raymoure, K.A. "pe-re-*82". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean. "PY 316 Tn (44)". DĀMOS: Database of Mycenaean at Oslo. University of Oslo.

- ↑ Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-521-29037-6. At Google Books.

- ↑ Homer (1899). Odyssey. Clarendon Press. p. 230. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ H.G. Liddell and R. Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- ↑ Martin P. Nilsson (1967), Die Geschichte der Griechische Religion, Volume I, C.F. Beck Verlag, p. 474

- ↑ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1179.

- 1 2 3 Smith, "Perse'phone"

- ↑ Comments about the goddess pe-re-*82 of Pylos tablet Tn 316, tentatively reconstructed as *Preswa

- ”It is tempting to see...the classical Perse...daughter of Oceanus...; whether it may be further identified with the first element of Persephone is only speculative.” John Chadwick. Documents in Mycenean Greek. Second Edition

- ↑ Cicero. De Natura Deorum 2.26

- ↑ Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood, "Persephone" The Journal of Hellenic Studies 98 (1978:101–121).

- ↑ Peter Kingsley, in Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition (Oxford University Press, 1995).

- ↑ Orphic Hymn 29.16

- ↑ Schol. ad. Theocritus 2.12

- ↑ In the Hymn to Melinoe, where the father is Zeus Chthonios, either Zeus in his chthonic aspect, or Pluto; Radcliffe G. Edmonds III, "Orphic Mythology," in A Companion to Greek Mythology (Blackwell, 2011), p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Rhode (1961), Psyche I, pp. 206–210

- 1 2 Nilsson (1967) Vol I, pp. 478–480

- ↑ Orphic Hymn 29 to Persephone

- ↑ "PERSEPHONE - Greek Goddess of Spring, Queen of the Underworld (Roman Proserpina)".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Nilsson (1967) Vol I, pp. 463–466

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nilsson, pp. 477–480 :"The Arcadian Great goddesses"

- ↑ Pausanias.Description of Greece 5.15.4, 5, 6

- ↑ Homeric Hymn to Demeter, 17.

- ↑ Nilsson (1967), Vol I, p. 463

- 1 2 "In Greek mythology Nysa is a mythical mountain with unknown location, the birthplace of the god Dionysos.": Fox, William Sherwood (1916), The Mythology of All Races, v.1, Greek and Roman, General editor, Louis Herbert Gray, p.217

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burkert (1985), pp. 285–290.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burkert (1985) p. 42

- ↑ Burkert (1985) pp. 40–45

- ↑ Martin Nilsson (1967) Vol I, pp. 453-455

- 1 2 Charon, "glad", probably euphemistically "death". Liddell and Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1843, 1985 printing), entries on χαροπός and χάρων, pp. 1980–1981; Brill's New Pauly (Leiden and Boston 2003), vol. 3, entry on "Charon", pp. 202–203.

- 1 2 3 J.Sakellarakis (1987). Herakleion Museum. Illustrated guide to the Museum. Ekdotike Athenon, p. 64 (Gallery VIII case No. 184)

- ↑ Kerenyi (1976), Dionysos, archetypal image of indestructible life.Princeton University Press. p. 24

- 1 2 Karl Kerenyi (1967). Eleusis. Archetypal image of mother and daughter. Princeton University Press. p. 31f

- ↑ Burkert (1985) p. 289

- ↑ ἕν ἀνδρῶν, ἕν θεῶν γένος, "One is the nature of men, another one the nature of gods": Erwin Rhode (1961), Psyche I p. 293

- ↑ Burkert p.12

- ↑ J.Frazer The Golden Bough, Part IV, Adonis, Attis and Osiris

- 1 2 F.Schachermeyer (1972), Die Minoische Kultur des alten Kreta, W.Kohlhammer Stuttgart, pp. 141, 308

- ↑ Thera and the Aegean World I, 1978, Publ. Thera and the Aegean, p. 669 ISBN 0-9506133-0-4 (A. Furumark: Thera catastrophe, Consequencies for the European civilization)

- ↑ A series of four daemons on a seal from Phaistos: Nilsson (1967) Vol I, pp. 294297 , Tf 22,3

- ↑ Nilsson (1967), Vol I , pp. 294–297

- ↑ "Daemon between two lions (Mycenea)". "Man between daemons (Phigalia)": Nilsson (1967), Vol I, pp. 294–297, Tf 20,7 TF 19,6

- ↑ Burkert (1985) pp. 34-40

- ↑ Burkert (1985) p. 40

- 1 2 "Hermes and the Anodos of Pherephata": Nilsson (1967) p. 509 taf. 39,1

- 1 2 F.Schachermeyer (1967) p. 144

- ↑ Burkert (1985), p. 24

- ↑ Karl Kerenyi (1976), Dionysos: archetypal image of indestructible life, pp. 89, 90 ISBN 0-691-02915-6

- ↑ Hesychius, listing of ἀδνόν, a Cretan-Greek form for ἁγνόν, "pure"

- ↑ Kerenyi(1976), p.24

- ↑ "To what extent one can and must differentiate between Minoan and Mycenaean religion is a question which has not yet found a conclusive answer" :.Burkert (1985). p. 21.

- 1 2 Bernard Clive Dietrich (1974). The Origins of the Greek Religion. Walter and Gruyter & Co. pp. 65–66 ISBN 3-11-003982-6

- ↑ Nilsson (1967) pp. 274–276, 713

- ↑ Bowra (1957), pp. 44–46

- ↑ G .Mylonas (1932). Eleusiniaka. I,1 ff

- ↑ Nilsson (1967), pp. 463–465

- ↑ John Chadwick (1976).The Mycenean World. Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Nilsson. (1967). Vol I, pp. 473–474

- 1 2 "In Greek mythology Achileus becomes immortal by the divine fire. His heel was his only mortal element, because it was not touched by the fire : Wunderlich (1972), The secret of Crete p. 134

- ↑ Pausanias :8.25, 4 -8.42 -8.37, 1ff. :Nilsson (1967) Vol I, p. 479,480

- ↑ Martin Robertson (1959). La peinture Grecque. Edition d'art Albert Skira. Geneve p.31, National Archaeological Museum of Athens, No2665

- ↑ "procession of daemons in front of a goddess on a goldring from Tiryns." Martin Nilsson (1967) Vol I, p. 293

- ↑ " Despoine was her surname among the many, just as they surnamed Demeter's daughter by Zeus Kore": Pausanias 8.37.1,8.38.2

- 1 2 "Pausanias 8.37.9". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ↑ Wunderlich (1972), The secret of Crete p. 284

- ↑ Nilsson (1967), p.311

- ↑ Janda (2010), pp. 16–44

- ↑ Testimonia of Pherecydes in an early 5th-century BC fragment, FGrH 3, 178, in the context of a discussion on the name of Dionysus: "Nũsas (acc. pl.), he [Pherecydes] said, was what they called the trees."

- ↑ The axis mundi of Indo-European mythology is represented both as a world-tree and as a world-mountain: Janda (2010), pp. 16–44

- ↑ "Loves of Hermes : Greek mythology". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- 1 2 Hesiod, Theogony 914.

- ↑ Homeric Hymn to Demeter, 4–20, 414–434.

- 1 2 "Theoi Project - Persephone". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ↑ Gantz, p. 65.

- ↑ Gantz, p. 67.

- 1 2 Reference to the Thesmophoria in Lucian's Dialogues of the Courtesans 2.1.

- ↑ The figures are unmistakable, as they are inscribed "Persophata, Hermes, Hekate, Demeter"; Gisela M. A. Richter, "An Athenian Vase with the Return of Persephone" The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 26.10 (October 1931:245–248)

- ↑ Suidas s.v. Makariai, with English translation at Suda On Line, Adler number mu 51

- ↑ William Hansen (2005) Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans (Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 180–182.

- ↑ Hansen, Classical Mythology, p. 182.

- 1 2 Ap. Athanassakis (2004), Hesiod. Theogony, Works and Days, Shield ,Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 56.

- ↑ The Anthesteria Bibliotheca Arcana (1997)

- ↑ Martin Nilsson (1967). Vol I, pp. 215–219

- 1 2 "Martin Nilsson, The Greek popular religion, The religion of Eleusis, pp 51-54". Sacred-texts.com. 2005-11-08. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ↑ Martin Nilsson (1967) Vol I, pp. 473–474

- ↑ Pausanias 2.30.2

- ↑ Nilsson, VoI, p. 444

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library 1.3.

- ↑ Homer. Odyssey, 10.494

- ↑ Orphica, 26, 71

- ↑ Odyssey 10.491, 10.509

- ↑ Károly Kerényi, Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter, 1967, passim

- ↑ Burkert (1985), pp. 285–289

- 1 2 Burkert (1985), pp. 240–243

- ↑ Clinton, Greek Sanctuaries, p. 113.

- 1 2 Potniai: Pelarge daughter of Potnieus is connected with the cult of Demeter in the Cabeirian : Pausanias 9.25,8, Nilsson (1967) Vol I pp. 151, 463

- ↑ Pseudo Apollodorus Biblioteca IV.2

- ↑ Kevin Klinton (1993), Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches, Routledge, p. 11

- ↑ Burkert (1985), p. 42

- ↑ Nilsson (1967) Vol I, pp. 463–465

- ↑ Pausanias 1.14,1: Nilsson (1967), Vol I, pp. 668–670

- ↑ Pausanias I 42,6 , Nilsson (1967), Vol I, p. 463

- 1 2 Nilsson (1967), Vol I, pp. 668–670

- ↑ Scholia ad. Euripides Phoen. 487

- ↑ Pausanias 9.25.5

- 1 2 Diodorus Siculus (v.4.7) :"At Thebes or Delos the festival occurred two months earlier, so any seed-sowing connection was not intrinsic."

- ↑ For Mantinea, see Brill's New Pauly "Persephone", II D.

- ↑ L. H. Jeffery (1976). Archaic Greece: The Greek city states c. 800-500 B.C (Ernest Benn Limited) p. 23 ISBN 0-510-03271-0

- ↑ "Pausanias 8.37.1,8.38.2". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ↑ "Reconstruction of interior of Sanctuary of Despoina". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 16: Nilsson (1967) ,Vol I, p. 464

- ↑ Brill's New Pauly, "Persephone", citing Diodorus 5.4

- ↑ Livy: 29.8, 29.18

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "perseus tufts-persephone". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ↑ "Virgil: Aeneid IV". Poetryintranslation.com. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ↑ "Persephone (Daughters of Zeus, #1)".

- ↑ "Persephone's Orchard".

- ↑ Santo, Suzanne Banay (2012). Persephone Under the Earth. Red Butterfly Publications. ISBN 0-988-09140-2.

Sources

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921.

- Bowra Maurice (1957), The Greek experience. The World Publishing Company, Cleveland and New York.

- Burkert Walter (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press . ISBN 0-674-36281-0

- Farnell, Lewis Richard (1906), The Cults of the Greek States, Volume 3 (Chapters on: Demeter and Kore-Persephone; Cult-Monuments of Demeter-Kore; Ideal Types of Demeter-Kore).

- Gantz, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0801853609 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0801853623 (Vol. 2).

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919.

- Janda, Michael (2010), Die Musik nach dem Chaos. Innsbruck

- Kerenyi Karl (1967), Eleusis: Archetypal image of mother and daughter . Princeton University Press.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1976), Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, Princeton: Bollingen, Google Books preview

- Nilsson Martin (1967), Die Geschichte der Griechischen Religion, Vol I, C.F Beck Verlag, Muenchen. Revised ed.

- Nilsson Martin (1950), Minoan-Mycenaean Religion, and its Survival in Greek Religion, Lund:Gleerup. Revised 2nd ed.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918.

- Rohde Erwin (1961), Psyche. Seelenkult und Unsterblichkeitsglaube der Griechen. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellshaft. Darmstad. (First edition 1893): full text in German downloadable as pdf.

- Rohde Erwin (2000), Psyche: The Cult of Souls and the Belief in Immortality among the Greeks , trans. from the 8th edn. by W. B. Hillis (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1925; reprinted by Routledge, 2000), online

- Schachermeyr Fritz (1964), Die Minoische Kultur des alten Kreta, W.Kohlhammer Verlag Stuttgart.

- Stephen King (2008), Duma Key

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Perse'phone"

- Zuntz Günther (1973), Persephone: Three Essays on Religion and Thought in Magna Graecia

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Persephone. |

- Martin Nilsson. The Greek popular religion

- Adams John Paul. Mycenean divinities

- Theoi project:Persephone Goddess

- Theoi project:The Rape of Persephone

- The Princeton Encyclopedia of classical sites:Despoina

- Theoi project:Despoine

- Kore Photographs

- Flickr users' photos tagged with Persephone