Occitania

Occitania (Occitan: Occitània, IPA: [uksiˈtanjɔ], [ukʃiˈtanjɔ], [usiˈtanjɔ], [uksiˈtanja] or [utsiˈtanjɔ],[1][2] also sometimes lo País d'Òc, "the Oc Country") is the historical region in southern Europe where Occitan was historically the main language spoken, and where it is sometimes still used, for the most part as a second language. This cultural area roughly encompasses the southern half of France, as well as Monaco and smaller parts of Italy (Occitan Valleys, Guardia Piemontese) and Spain (Aran Valley). Occitania has been recognized as a linguistic and cultural concept since the Middle Ages, but has never been a legal nor a political entity under this name, although the territory was united in Roman times as the Seven Provinces (Latin: Septem Provinciæ[3]) and in the early Middle Ages (Aquitanica or the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse[4]) before the French conquest started in the early 13th century.

.svg.png)

Currently about a half million people out of 16 million in the area have a proficient knowledge of Occitan,[5] although the languages more usually spoken in the area are French, Italian, Catalan and Spanish. Since 2006, the Occitan language has been an official language of Catalonia, which includes the Aran Valley where Occitan gained official status in 1990.

Under later Roman rule (after 355), most of Occitania was known as Aquitania,[6] itself part of the Seven Provinces within a wider Provincia Romana (modern Provence), while the northern provinces of what is now France were called Gallia (Gaul). Gallia Aquitania (or Aquitanica) is thus also a name used since medieval times for Occitania (i.e. Limousin, Auvergne, Languedoc and Gascony), including Provence as well in the early 6th century. Thus the historic Duchy of Aquitaine must not be confused with the modern French region called Aquitaine: this is the main reason why the term Occitania was revived in the mid-19th century. The names "Occitania"[7] and "Occitan language" (Occitana lingua) appeared in Latin texts from as early as 1242–1254[8] to 1290[9] and during the following years of the early 14th century; texts exist in which the area is referred to indirectly as "the country of the Occitan language" (Patria Linguae Occitanae). This derives from the name Lenga d'òc that was used in Italian (Lingua d'òc) by Dante in the late 13th century. The somewhat uncommon ending of the term Occitania is most probably a portmanteau French clerks coined from òc [ɔk] and Aquitània [ɑkiˈtanjɑ], thus blending the language and the land in just one concept.[10] Occitan and Lenga d'òc both refer to the centuries-old set of Romance dialects that use òc for "yes".

Geography

Occitania includes the following regions:

- The southern half of France: Provence, Drôme-Vivarais, Auvergne, Limousin, Guyenne, Gascony, southern Dauphiné and Languedoc. French is now the dominant language in this area, where Occitan is not recognized as an official language.

- The Occitan Valleys in the Italian Аlps, where the Occitan language received legal status in 1999. These are fourteen Piedmontese valleys in the provinces of Cuneo and Torino, as well as in scattered mountain communities of the Liguria region (province of Imperia), and, unexpectedly, in one community (Guardia Piemontese) in the region of Calabria (province of Cosenza).

- The Aran valley, in the Pyrenees, in Catalonia (Spain) where Occitan has been an official language since 1990 (status granted by the partial autonomy of Aran Valley, then confirmed by the Catalan Statute)

- The Principality of Monaco (where Occitan is traditionally spoken besides Monégasque).

Occitan or langue d'oc (lenga d'òc) is a Latin-based Romance language in the same way as Spanish, Italian or French. There are six main regional varieties, with easy inter-comprehension among them: Provençal (including Niçard spoken in the vicinity of Nice), Vivaroalpenc, Auvernhat, Lemosin, Gascon (including Bearnés spoken in Béarn) and Lengadocian. All these varieties of the Occitan language are written and valid. Standard Occitan is a synthesis which respects soft regional adaptations. See also Northern Occitan and Southern Occitan.

Catalan is a language very similar to Occitan and there are quite strong historical and cultural links between Occitania and Catalonia.

History

Written texts in Occitan appeared in the 10th century: it was used at once in legal then literary, scientific or religious texts. The spoken dialects of Occitan are centuries older and appeared as soon as the 8th century, at least, revealed in toponyms or in Occitanized words left in Latin manuscripts, for instance.

Occitania was often politically united during the Early Middle Ages, under the Visigothic Kingdom and several Merovingian and Carolingian sovereigns. In Thionville, nine years before he died (805), Charlemagne vowed that his empire be partitioned into three autonomous territories according to nationalities and mother tongues: along with the Franco-German and Italian ones, was roughly what is now modern Occitania from the reunion of a broader Provence and Aquitaine.[12] But things did not go according to plan and at the division of the Frankish Empire (9th century), Occitania was split into different counties, duchies and kingdoms, bishops and abbots, self-governing communes of its walled cities. Since then the country was never politically united again, though Occitania was united by a common culture which used to cross easily the political, constantly moving boundaries. Occitania suffered a tangle of varying loyalties to nominal sovereigns: from the 9th to the 13th centuries, the dukes of Aquitaine, the counts of Foix, the counts of Toulouse and the Counts of Barcelona rivalled in their attempts at controlling the various pays of Occitania.

Occitan literature was glorious and flourishing at that time: in the 12th and 13th centuries, the troubadours invented courtly love (fin'amor) and the Lenga d'Òc spread throughout all European cultivated circles. Actually, the terms Lenga d'Òc, Occitan, and Occitania appeared at the end of the 13th century.

But from the 13th to the 17th centuries, the French kings gradually conquered Occitania, sometimes by war and slaughtering the population, sometimes by annexation with subtle political intrigue. From the end of the 15th century, the nobility and bourgeoisie started learning French while the people stuck to Occitan (this process began from the 13th century in two northernmost regions, northern Limousin and Bourbonnais). In 1539, Francis I issued the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts that imposed the use of French in administration. But despite measures such as this, a strong feeling of national identity against the French occupiers remained and Jean Racine wrote on a trip to Uzès in 1662: "What they call France here is the land beyond the Loire, which to them is a foreign country."[13]

In 1789, the revolutionary committees tried to re-establish the autonomy of the "Midi" regions: they used the Occitan language, but the Jacobin power neutralized them.

The 19th century witnessed a strong revival of the Occitan literature and the writer Frédéric Mistral was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1904.

But from 1881 onwards, children who spoke Occitan at school were punished in accordance with minister Jules Ferry's recommendations. That led to a deprecation of the language known as la vergonha (the shaming): the whole fourteen million inhabitants of the area spoke Occitan in 1914,[14] but French gained the upper hand during the 20th century. The situation got worse with the media excluding the use of the langue d'oc. In spite of that decline, the Occitan language is still alive and gaining fresh impetus.

Outer settlements

Although not really a colony in a modern sense, there was an enclave in the County of Tripoli. Raymond IV of Toulouse founded it in 1102 during the Crusades north of Jerusalem. Most people of this county came from Occitania and Italy and so the Occitan language was spoken.

Today

There are 14 to 16 million inhabitants in Occitania today. According to the 1999 census, there are 610,000 native speakers and another million people with some exposure to the language. Native speakers of Occitan are to be found mostly in the older generations. The Institut d'Estudis Occitans (IEO) has been modernizing the Occitan language since 1945, and the Conselh de la Lenga Occitana (CLO) since 1996. Nowadays Occitan is used in the most modern musical and literary styles such as rock 'n roll, folk rock (Lou Dalfin), rap (Fabulous Trobadors), reggae (Massilia Sound System) and heavy metal, detective stories or science-fiction. It is represented on the internet. Association schools (Calandretas) teach children in Occitan.

The Occitan political movement for self-government has existed since the beginning of the 20th century and particularly since post-war years (Partit Occitan, Partit de la Nacion Occitana, Anaram Au Patac, Iniciativa Per Occitània, Paratge, Bastir! etc.). The movement remains negligible in electoral and political terms. Nevertheless, Regional Elections in 2010 allowed the Partit Occitan to enter the Regional councils of Aquitaine, Auvergne, Midi-Pyrénées, and Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur.

Major demonstrations in Carcassonne (2005 and 2009) and Béziers (2007) and the week-long Estivada festivals in Rodez (2006–2010) suggest that there is a revival of Occitan language and culture. However, in France, Occitan is still not recognized as an official language, as the status of French has been constitutionally protected since 1992, and Occitan activists want the French government to adopt Occitan as the second official language for seven regions representing the South of France.

Culture

Literature

- Troubadourisme was the first notable element of a proper Occitan culture. Those poets from the High Middle Ages were highly appreciated for their refined lyricism and eventually gained popularity throughout Europe. Troubadourisme remained a tradition during centuries and its members were mainly from the aristocracy. William IX, Duke of Aquitaine and Bertran de Born epitomized that movement.

- Occitan literature faced a rebirth during the Baroque period mainly in Gascony through the Béarnese dialect. Indeed, Henri IV of France whose mother-tongue was Bearnese, was designed King of France. That nomination provoked a relative enthusiasm for Bearnese literature with the publication of works by Pey de Garros and Arnaud de Salette. Toulouse was also an important place for that rebirth, especially through the poems of Pèire Godolin. Nonetheless, Occitan literature following the death of Henri IV had an important phase of decline, symbolised by the fact that local poets, as Clément Marot, begun to write in French language.

- Frédéric Mistral and his Félibrige school marked the renewal of Occitan language in literature in the middle of the 19th century. Mistral won the 1904 Nobel Prize in literature, illustrating the curiosity about the Provençal dialect, - considered as an exotic language -, in France and in Europe, where Irish soldier and poet William Bonaparte-Wyse decided to compose in the Provençal dialect of Occitan.

- The Acadèmia dels Jòcs Florals (Academy of the Floral games) held every year in Toulouse is considered one of the oldest literary institution of the Western World (founded in 1323). Its main purpose is to encourage Occitan poetry.

- In 1945 was created the cultural association Institut d'Estudis Occitans (Occitan Studies Institute) by a group of Occitan and French writers such as Jean Cassou, Tristan Tzara and Renat Nelli. Its purpose is to maintain and develop the language and influence of Occitania, mainly through the promotion of local literature and poetry.

Music

Romantic composer Gabriel Fauré was born in Pamiers, Ariège in the Pyrenees region of France.

- The Romantic music composer Déodat de Séverac was born in the region, and, following his schooling in Paris, he returned to the region to compose. He sought to incorporate the music indigenous to the area in his compositions.

Gastronomy

The Occitanian gastronomy or occitan cuisine is considered as Mediterranean but has some specific features that separate it from the Catalan cuisine or Italian cuisine. Indeed, because of the size of Occitania and the great diversity of landscapes- from the mountaineering of the Pyrenees and the Alps, rivers and lakes, and finally the Mediterranean and Atlantic coast – it can be considered as a highly varied cuisine. Compared to other Mediterranean cuisines, we could note the using of basic elements and flavors, among them meat, fish and vegetables, moreover the frequent using of the olive oil; although also compound of elements from the Atlantic coast cuisine, with cheeses, pastes, creams, butters and more high calorie food. Among well-renowned meals common on the Mediterranean coast includes ratatolha (the equivalent of Catalan samfaina), alhòli, bolhabaissa (similar to Italian Brodetto alla Vastese), pan golçat (bread with olive oil) likewise salads with mainly olives, rice, corn and wine. Another significant aspect that changes compared to its Mediterranean neighbors is the abundant amount of aromatic herbs; some of them are typically Mediterranean, like parsley, rosemary, thyme, oregano or again basil.

Some of the world-renowned traditional meals are Provençal ratatolha (ratatouille), alhòli (aioli) and daube (Provençal stew), Niçard salada nissarda (Salad Niçoise) and pan banhat (Pan-bagnat), Limousin clafotís (clafoutis), Auvergnat aligòt (aligot), Languedocien caçolet (cassoulet), or again Gascon fetge gras (foie gras).

Occitania is also home of a great variety of cheeses (like Roquefort, Bleu d'Auvergne, Cabécou, Cantal, Fourme d'Ambert, Laguiole, Pélardon, Saint-Nectaire, Salers) and a great diversity of wines such as Bordeaux, Rhône wine, Gaillac wine, Saint-Émilion wine, Blanquette de Limoux, Muscat de Rivesaltes, Provence wine, Cahors wine, Jurançon. Alcohols such as Pastis and Marie Brizard or brandies such as, Armagnac, and Cognac are produced in the area.

Image gallery

Saint-Sernin's Basilica's chevet, Toulouse. The largest Romanesque church in Europe.

Saint-Sernin's Basilica's chevet, Toulouse. The largest Romanesque church in Europe. Global view of the village of Conques.

Global view of the village of Conques._10.jpg) View of the episcopal city of Albi.

View of the episcopal city of Albi. View of the Old Town of the colorful city of Menton, on the French Riviera.

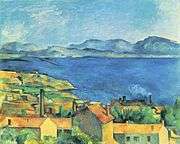

View of the Old Town of the colorful city of Menton, on the French Riviera. View of Marseilles, the largest city in Southern France.

View of Marseilles, the largest city in Southern France. The Cistercian abbey of Sénanque.

The Cistercian abbey of Sénanque.

Gorges du Verdon Canyon.

Gorges du Verdon Canyon.

One of the many lakes of the Mercantour National Park, in the French Alps.

One of the many lakes of the Mercantour National Park, in the French Alps. The fortified town of Carcassonne, Aude.

The fortified town of Carcassonne, Aude. The Roman Pont du Gard.

The Roman Pont du Gard. The headquarters of Michelin, Clermont-Ferrand.

The headquarters of Michelin, Clermont-Ferrand.

.jpg) A surfer at Soorts-Hossegor, considered as one of the best surfing spots in the world.[15]

A surfer at Soorts-Hossegor, considered as one of the best surfing spots in the world.[15] Cannes during the festival period.

Cannes during the festival period. University of Montpellier's Faculty of Medicine, the oldest and still-active medical school in the world[16]

University of Montpellier's Faculty of Medicine, the oldest and still-active medical school in the world[16]

Notable people associated with Occitania

This is a non-exhaustive list of people who were born in the Occitania historical territory (although it is difficult to know the exact boundaries), or notable people from other regions of France or Europe with Occitan roots, or notable people from other regions of France or Europe who have other significant links with the historical region. One may note that this article, 'Notable people from Occitania', is compound for a large part of personalities from the historical region of Occitania and/or who own an Occitan patronym and/or who lived for the major part of their lives in the Occitania historical territory, yet an important part of the list members still can't be considered as belonging to the Occitan historical heritage, mainly due to their mother-tongue, French.

Writers, playwrights and poets

- Petronius, courtier during the reign of Nero from Massalia, he is believed to have written the Satyricon.

- Ausonius, 4th-century Roman poet from Burdigalia.

- Bertran de Born, 12th-century troubadour.

- Comtessa de Dia, 12th-century trobairitz (female troubadour).

- Jaufre Rudel, early–mid 12th century-troubadour.

- Arnaut Daniel, late 12th-century troubadour, famous for his appearance on the Divine Comedy of Italian poet Dante.

- Bernard de Ventadour, 12th-century troubadour.

- Peire Cardenal, 13th-century troubadour.

- Antoine de la Sale, 15th-century courtier, educator and writer.

- Mellin de Saint-Gelais, Poet Laureate of Francis I of France.

- Clément Marot, 16th-century Renaissance poet.

- Théodore Agrippa d'Aubigné, early 17th-century Baroque poet.

- Bartas, 17th-century poet who wrote both in French and in Occitan.

- Honoré d'Urfé, 17th-century Pastoral writer.

- Jean-Louis Guez de Balzac, 17th-century Baroque author.

- La Rochefoucauld, 17th-century moralist born in Paris to the famous noble Rochefoucauld family whose origins go back to Charente, where he had his residence.

- Théophile de Viau, 17th-century Baroque poet and dramatist.

- Cyrano de Bergerac, 17th-century novelist and playwright. He was from a Dordognaise aristocratic family from Bergerac, although he never lived there in his entire life.

- Fénelon, 17th-century Renaissance writer.

- Nicolas Chamfort, 18th-century poet, member of the Jacobin club.

- Marquis de Sade, 18th-century aristocrat, revolutionary politician, philosopher, and writer. Born in Paris, he was the heir of the Provençal Sade house, one of the oldest family of the region. He was thus Lord of Saumane, Lacoste and Co-Lord of Mazan where he had several residences, including the famous Château de Lacoste.

- Marquis de Pompignan, 18th-century man of letter.

- Luc de Clapiers, marquis de Vauvenargues, 18th-century moralist.

- Baron de Montesquieu, an important writer and philosopher of the 18th-century Enlightenment.

- Jean-François Marmontel, historian and novelist, member of the Encyclopédistes movement.

- Fleury Mesplet, founder of the Montreal Gazette (1778).

- Jansemin, 19th-century Occitan language poet.

- Comte de Lautréamont, 19th-century poet born in Uruguay to François Ducasse (consular officer) and his wife Jacquette-Célestine Davezac, both from Southwestern France from which they returned when Ducasse was thirteen, in Tarbes and later in Pau where the poet begun to write his first works.

- Émile Augier, 19th-century dramatist.

- Honoré de Balzac, 19th-century realist writer. Born in Tours, he was the son of Bernard François Balssa, an administrator from the Tarn department in South West France, who was despatched to Tours to coordinate supplies for the Army during the Directory. François changed his name to the more noble sounding Balzac, and his son Honoré later added—without official recognition—the nobiliary particle: "de".[18] According to André Maurois and Philibert Auberrand, the original family name Balssa came from the radical bals which in Occitan means "steep rock".[19] · [20] Another commonly admitted theory is that Balssa came from the Occitan balsan, derived from Late Latin balteanus, describing a horse with white patches on its paws.

- André Antoine, actor, theatre manager, film director, author, and critic as well as one of the leading member of the Naturalist movement.

- Théophile Gautier, 19th-century poet and writer.

- Jules Vallès, 19th-century writer.

- Émile Gaboriau, 19th-century writer, journalist and novelist.

- Alphonse Daudet, 19th-century novelist.

- Pierre Loti, 19th-century novelist and naval officer.

- Frédéric Mistral, 19th-century and early 20th-century Occitan-language poet and 1904 Nobel Prize in Literature winner. Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral chose her pen name after him.

- Théodore Aubanel, 19th-century poet.

- Edmond Rostand, late 19th-century playwright and novelist.

- Charles Maurras, late 19th-century and 20th-century influential poet, author and critic.

- Paul Valéry, 20th-century poet

- Jean Paulhan, 20th-century writer and intellectual

- Pierre Reverdy, 20th-century poet

- André Gide, 20th-century writer and 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Born in Paris, his family was from Uzès, in the Gard department. He was from an old Protestant family from Southern France. His father Paul Gide and his uncle Charles Gide, were both born in Uzès. Gide is a popular last name in the Gard and Bouches du Rhône departments.[21]

- Francis Jammes, 20th-century lyrical poet

- Jean Giraudoux, 20th-century novelist, essayist and playwright.

- Jules Romains, 20th-century poet and writer, founder of the Unanimism literary movement.

- Francis Ponge, 20th-century poet and essayist.

- Léon Bloy, 20th-century writer.

- Jean Anouilh, 20th-century playwright.

- René Char, 20th-century poet.

- François Mauriac, 20th-century writer and 1952 Nobel Prize in Literature winner.

- Marcel Pagnol, 20th-century writer

- Marguerite Duras, 20th-century writer. Born Marguerite Donnadieu in French Indochina, she chose her pen name after Duras, the commune her parents originated from, in the Lot-et-Garonne department.

- Jean Giono, 20th-century writer.

- Antonin Artaud, 20th-century dramatist, poet, essayist, actor, and theatre director.

- Pierre Boulle, 20th-century writer.

- Françoise Sagan, 20th-century novelist, screenwriter and playwright

- Marcela Delpastre, 20th-century Occitan-language writer.

- Jean Vilar, theatre director and actor, founder of the Festival d'Avignon.

- Anne Desclos, 20th-century journalist and novelist.

- Joan Bodon, 20th-century Occitan-language writer. His mother, Albanie Boudou (née Balssa), was said to be connected by blood with 19th-century novelist Honoré de Balzac.[22]

- Jean Echenoz, 20th-century writer.

- J. M. G. Le Clézio, 20th-century writer and poet, 2008 Nobel Prize in Literature winner.

- Philippe Sollers, 20th-century writer and critic.

- Romain Puertolas, contemporary writer.

- Charles Dantzig, contemporary writer.

Philosophers

- Isaac the Blind, medieval kabbalistic philosopher.

- Samuel ibn Tibbon, medieval philosopher and doctor.

- Gersonides, medieval philosopher, Talmudist, mathematician, physician, astronomer and astrologer.

- Pierre Bayle, philosopher and writer, forerunner of the Encyclopedists and an advocate of the principle of the toleration of divergent beliefs, his works subsequently influenced the development of the Enlightenment.

- Étienne de La Boétie, judge, writer and philosopher known for his Discourse on Voluntary Servitude.

- Michel de Montaigne, one of the most influential writers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre. His works influenced writers all over the world such as René Descartes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau or again Ralph Waldo Emerson and Friedrich Nietzsche.

- Pierre Gassendi, philosopher and mathematician. His best known intellectual project attempted to reconcile Epicureanism atomism with Christianity.

- Blaise Pascal, mathematician, physicist, inventor, writer and Christian philosopher. He started some pioneering work on calculating machines as a teenager. After three years of effort and fifty prototypes, he was one of the first two inventors of the mechanical calculator. Later, he developed a method to solve the Problem of points, giving birth during the 18th Century to the probabilities calculation, his works still strongly influence modern economic theories and social science.

- Maine de Biran, 18th-century Spiritualist philosopher.

- Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, essayist and political theorist of the French revolution. He also made significant theoretical contributions to the nascent social sciences.

- Pierre Jean George Cabanis, 18th-century physiologist and Materialist philosopher.

- Auguste Comte, philosopher, he was a founder of the discipline of sociology and of the doctrine of positivism. He is sometimes regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term.

- Charles Bernard Renouvier, 19th-century philosopher.

- Jean Hyppolite, philosopher, known for championing the work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, philosopher and Jesuit priest, who trained as a paleontologist and geologist and took part in the discovery of Peking Man. He conceived the idea of the Omega Point (a maximum level of complexity and consciousness towards which he believed the universe was evolving) and developed Vladimir Vernadsky's concept of noosphere.

- Louis Lavelle, 20th-century philosopher, influenced by Continental philosophy and Spiritualism.

- Jean Cavaillès, 20th-century philosopher and mathematician who took part in the French Resistance within the Libération movement. He came from a long line of Huguenot officers from the South West of France. His last name, Cavaillès, derivates from cavalh, the Occitan word for horse.

- Henri Lefebvre, 20th-century Marxist philosopher and sociologist.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, 20th-century philosopher, playwright, novelist and political activist. Born in Paris, his family originated from Thiviers, in Dordogne where young Sartre spent his holidays.[23] His last name Sartre, came from "satre", the occitan word for "tailor".

- Paul Ricœur, 20th Century philosopher, tbest known for combining phenomenological description with hermeneutics.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, 20th-century phenomenological philosopher.

- Henri Lefebvre, Marxist philosopher and sociologist.

- Georges Canguilhem, philosopher and physician, specialized in the philosophy of science.

- Georges Bataille, 20th-century influential intellectual and literary figure.

- Pierre Bourdieu, sociologist, anthropologist and philosopher, his sociological work is dominated by the analysis of the reproduction mechanisms of the social hierarchies.

- Michel Serres, 20th-century philosopher, his works are generally focused on the scientific progress and its effect on our society.

- Georges Dumézil, comparative philologist. He was born in Paris to a Girondin family from Bayon.

- René Girard, 20th-century anthropological philosopher, historian and literary critic.

- Jacques Ellul, 20th-century philosopher, law professor, sociologist, lay theologian, and Christian anarchist.

- Alain Badiou, 20th-century marxist philosopher. Born in French Morocco, his father Raymond Badiou was mayor of Toulouse from 1944 to 1958. His last name, Badiou, comes from the Occitan badiu for simpleton.[24]

- Daniel Bensaïd, 20th-century Trotskyist philosopher.

- Jean-Luc Nancy, contemporary philosopher.

Scientists

- Tacitus, Roman historian, author of the Annals and the Histories, probably born in Gallia Narbonensis.

- Pope Sylvester II, Pope, prolific scholar and teacher who endorsed and promoted study of Arab and Greco-Roman arithmetic, mathematics, and astronomy, reintroducing to Europe the abacus and armillary sphere, which had been lost to Europe since the end of the Greco-Roman era.

- Gregory of Tours, Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours from Urbs Arverna. He is the main contemporary source for Merovingian history. His most notable work was his Decem Libri Historiarum or Ten Books of Histories, better known as the Historia Francorum ("History of the Franks").

- Guy de Chauliac, physician and surgeon, author of the influential treatise Chirurgia Magna.

- Jean de Roquetaillade, Franciscan alchemist

- Joseph Justus Scaliger, religious leader and scholar, considered as the father of Chronology.

- Bernard Palissy, potter, hydraulics engineer and craftsman, famous for his imitations of Chinese porcelain.

- Nostradamus, apothecary who published collections of prophecies that have since become famous worldwide. He was also a physician.

- Oronce Finé, mathematician and cartographer.

- Michel Rolle, mathematician, best known for the 1691 Rolle's theorem.

- Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, astronomer, antiquary and savant.

- Henri Pitot, hydraulic engineer, inventor of the Pitot tube and author of the Pitot theorem in plane geometry.

- Jean Astruc, professor of medicine, who wrote the first great treatise on syphilis and venereal diseases.

- Pierre de Fermat, amateur mathematician who is given credit for early developments that led to infinitesimal calculus, including his technique of adequality.

- Louis Bertrand Castel, mathematician and physician.

- Jean-Antoine Chaptal, chemist, physician, agronomist, industrialist, statesman, educator and philanthropist, discoverer of the chaptalizatio procedure.

- Louis Bertrand Castel, botanist.

- Louis Feuillée, botanist, astronomer and geographer.

- Michel Adanson, botanist and naturalist ; the Adansonia, commonly known as the baobab tree, was named after him.

- Jean-Baptiste Denys, physician, notable for having performed the first fully documented human blood transfusion.

- Réaumur, scientist who contributed to many different fields, especially entomology and metallography.

- Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, one of the most prominent figure of the late 16th century Botany.

- Charles Plumier, botanist and botany explorer, after whom the Frangipani genus Plumeria is named.

- François Laurent d'Arlandes, pioneer of hot air ballooning.

- Montgolfier brothers, inventors of the Montgolfière-style hot air balloon.

- Jean-Charles de Borda, mathematician and physicist, he developed the Borda count voting system and contributed to the construction of the standard metre, basis of the metric system.

- Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, chemist and physicist, famous for his two gas laws.

- Marc Seguin, engineer, inventor of the wire-cable suspension bridge and the multi-tubular steam-engine Firetube boiler.

- Bernard de Montfaucon, Benedictine monk regarded as one of the founders of modern archaeology.

- Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, phsyician who proposed a painless method for executions that inspired the guillotine.

- Jean-Baptiste Dumas, chemist, best known for his works on organic analysis and synthesis, as well as the determination of atomic weights (relative atomic masses) and molecular weights by measuring vapor densities.

- Marc René, marquis de Montalembert, military engineer.

- Philippe Pinel, physician who was instrumental in the development of a more humane psychological approach to the custody and care of psychiatric patients and pioneer of the moral therapy.

- Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, Swiss botanist, he came from one of the oldest noble families of Provence that moved to Switzerland at the end of the 16th century to escape religious persecution.

- Aimé Bonpland, explorer and botanist, who traveled with Alexander von Humboldt in Latin America from 1799 to 1804.

- Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, physician, author of the Coulomb's law . He gave the definition of the electrostatic force of attraction and repulsion, and did important work on friction.

- Jean-Baptiste Say, economist, famous for his law of markets. Born in Lyon, he was from a Protestant family who originated from Florac, in Lozère. The Say family moved to Nîmes after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes to finally reach Geneva, where his father was born. Say was a particularly popular last name in the Tarn-et-Garonne department at that time and its origins are quite murky.[25]

- Bertrand de Molleville, politician and scientist, inventor of the secateurs.

- René Lesson, surgeon, naturalist, ornithologist, and herpetologist.

- Louis-Sébastien Lenormand, chemist, physicist, inventor and the first pioneer in modern parachuting in the world.

- Dominique Jean Larrey, considered as the first modern military surgeon.

- François-Vincent Raspail, chemist, naturalist, physician and political figure, founder of Cytochemistry.

- François Arago, important mathematician, astronomer and physicist.

- Jean Pierre Flourens, physiologist and a pioneer in Anesthesia.

- Antoine Bussy, chemist, who is credited to have isolated the element beryllium, in 1828, the same year as Friedrich Wöhler.

- Élisée Reclus, renowned geographer, writer and anarchist, precursor of Social geography.

- Alphonse Borrelly, astronomer, who discovered an important number of asteroids and comets, including the periodic comet 19P/Borrelly.

- Philippe de Girard, uncredited inventor of the tin canning process and inventor of the first flax spinning frame in 1810. The industrial town of Żyrardów in Poland was thus named after him.

- Antoine Jérôme Balard, chemist, one of the discoverers of bromine.

- Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, physician and pedagogue, notably credited with describing the first case of Tourette syndrome. He was also educator of the deaf, and experienced his theories in the celebrated case of Victor of Aveyron.

- Frédéric Bastiat, economist, classical liberalist, he developed the economic concept of opportunity cost, and introduced the Parable of the broken window.

- Pierre Frédéric Sarrus, mathematician, known for having developed the Sarrus linkage.

- Jean-François Champollion, decipherer of the Egyptian hieroglyphs.

- Paulin Talabot, railway and canal engineer.

- Pierre André Latreille, famous zoologist, specialising in arthropods.

- Antoine Marfan, one of the most important figures of modern pediatrics and first describer of the Marfan syndrome.

- Henri Fabre, aviator and inventor of the first successful seaplane, the Fabre Hydravion.

- Charles Cros, poet and inventor, best known for being the first person to conceive a method for reproducing recorded sound, an invention he named the Paleophone.

- Charles Gaudichaud-Beaupré, botanist who made several expeditions in Oceania and South America.

- Jean Cruveilhier, pathologist and anatomist.

- Joseph Monier, gardener and one of the principal inventors of reinforced concrete.

- Guillaume Dupuytren, anatomist and military surgeon.

- Gabriel Tarde, sociologist, criminologist and social psychologist who conceived sociology as based on small psychological interactions among individuals.

- Georges Sagnac, physicist who lent his name to the Sagnac effect.

- Édouard Roche, astronomer and mathematician, best known for his work in celestial mechanics.

- Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran, chemist, discoverer of gallium, samarium and dysprosium.

- Jacques-Arsène d'Arsonval, physician, physicist, and inventor of the moving-coil D'Arsonval galvanometer and the thermocouple ammeter.

- Auguste Charlois, astronomer, who discovered around 99 asteroids.

- Jean Gaston Darboux, mathematician, he made several important contributions to geometry and mathematical analysis.

- Arthur Fallot, physician, who described in detail the four anatomical characteristics of the tetralogy of Fallot.

- Alphonse Beau de Rochas, engineer who originated the principle of the four-stroke internal-combustion engine.

- Émile Borel, mathematician, known for being along with Henri Lebesgue and René-Louis Baire one of the pioneers of the measure theory and its application to probability theory. He was also a politician and member of the French Resistance, and is regarded as one of the precursors of the European idea.

- Édouard Lartet, palaeontologist and one of the founders of modern palaeontology.

- Ernest Fourneau, medicinal chemist who made major contributions to the discovery of synthetic local anesthetics, as well as in the synthesis of suramin.

- Alfred Binet, psychologist who invented the first practical intelligence test, the Binet-Simon scale.

- Claude Gay, prominent botanist and naturalist of the Chilean flora.

- Michel Chevalier, engineer and economist.

- Joseph Valentin Boussinesq, mathematician and physician who made significant contributions to the theory of hydrodynamics and heat. He is the first developer of the Korteweg–de Vries equation.

- Albert Calmette ForMemRS, physician, bacteriologist and immunologist, who discovered the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin used in the BCG vaccine against tuberculosis. and conceived the first antivenom for snake venom known as the Calmette's serum.

- Émile Duclaux, microbiologist and chemist.

- Louis Mékarski, engineer and inventor who patented the Mekarski system of compressed-air powered trams.

- Louis Arthur Ducos du Hauron, one of the pioneers of color photography.

- Jean-Henri Fabre, prominent entomologist.

- Gaston Planté, physicist who invented the lead–acid battery in 1859. The lead-acid battery eventually became the first rechargeable electric battery marketed for commercial use.

- Guillaume Bigourdan, astronomer who won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1919.

- Clément Ader, aviation precursor.

- Charles Fabry, physicist, co-inventor of the Fabry–Pérot interferometer.

- Bernard Brunhes, geophysicist who discovered the Earth's magnetic field reversals.

- Giuseppe Peano, Italian mathematician, best known for his works in logic, born in Coni, in Piedmontese Occitania.

- Georges Jean Marie Darrieus, aeronautical engineer and inventor of the Darrieus rotor.

- Paul Vidal de La Blache, one of the most prominent figure of modern French geography.

- Pierre Paul Émile Roux, physician, bacteriologist and immunologist as well as co-founder of the Pasteur Institute and responsible for the Institute's production of the anti-diphtheria serum.

- Eugène Freyssinet, structural and civil engineer, precursor of prestressed concrete.

- Paul Broca, physician, surgeon, anatomist, and anthropologist.

- Madeleine Brès, the first French woman, and one of the first in Europe, to obtain a medical degree.

- Paul Sabatier, chemist, awarded of the 1912 Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Victor Grignard.

- Jean Cabannes, physicist, specializing in optics.

- Paul Dirac, English theoretical physicist who made fundamental contributions to the early development of both quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics. His paternal family originated from Dirac,[26] in South West France, and moved to Switzerland after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes to finally join Bristol where Paul was born.

- Henri Dulac, mathematician who refined the Bendixson–Dulac theorem.

- Marcellin Boule, palaeontologist.

- André Lichnerowicz, differential geometer and mathematical physicist.

- Jacques Cousteau, naval officer and explorer who co-developed the Aqua-Lung, pioneered marine conservation and helped to popularize Oceanography throughout the world.

- Paul Montel, mathematician, known for his notion of Normal family.

- Célestin Freinet, prominent pedagogue and educational reformer.

- Gaston Julia, mathematician, born in French Algeria to a Pyrenean family.

- René Grousset, historian and prominent specialist of the Asian history.

- Germaine Tillion, ethnologist and Resistant.

- Jean Dausset, immunologist, awarded of the 1980 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine along with Baruj Benacerraf and George Davis Snell.

- Edmond Malinvaud, economist.

- Maurice Duverger, sociologist and jurist, who developed the Duverger's law.

- Alexander Grothendieck German-born French mathematician who grew up in Montpellier where he attended the municipal University and lived for the rest of his live in Ariège as a hermit, until his death in 2014.

- Alfred Sauvy, demographer, anthropologist and historian who first coined the term Third World.

- Jean-Marie Souriau, mathematician, known for works in symplectic geometry, in which he was one of the pioneers.

- Jean-Pierre Serre, mathematician, who made fundamental contributions to algebraic topology, algebraic geometry, and algebraic number theory. He was awarded the Fields Medal in 1954, the Wolf Prize in 2000 and the Abel Prize in 2003, making him one of four mathematicians to achieve this (along with Pierre Deligne, John Milnor, and John G. Thompson).

- Jacques Le Goff, historian and eminent specialist of the Middle Ages, most specifically the 12th and 13th centuries.

- André Neveu, physicist who coinvented the Neveu-Schwarz algebra and the Gross-Neveu model.

- Jacques-Louis Lions, mathematician, awarded of the 1991 Japan Prize and Harvey Prize. He is listed as an ISI highly cited researcher. He was elected president of the International Mathematical Union in 1991.

- Robert Lafont, linguist.

- Frank Merle, mathematician, specializing in partial differential equations and mathematical physics, awarded of the 2005 Bôcher Prize.

- Albert Fert, physicist, one of the discoverers of giant magnetoresistance which brought about a breakthrough in gigabyte hard disks, awarded of the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physics, together with Peter Grünberg.

- Alain Connes, mathematician, who revolutionned the Von Neumann algebra, resolving major problems on this field, notably the classification of the Type III factors. He was awarded of the 1982 Fields Medal.

- Pierre-Paul Grassé, zoologist.

- Bernard Gregory, physicist, former director-general of CERN.

- Christian Metz, film theorist and semiologist.

- Pierre-Louis Lions, mathematician, who received the 1994 Fields Medal for his works on nonlinear partial differential equations.

- Michel Talagrand, mathematician, specializing in functional analysis and probability theory.

- Alain Colmerauer, computer scientist and creator of the logic programming language Prolog.

- Michel Broué, mathematician, specializing in algebraic geometry and representation theory.

- Cédric Villani, mathematician, awarded of the 2010 Fields Medal for his works on partial differential equations and mathematical physics

- Jean-Jacques Laffont, economist, specializing in public economics and information economics, he was awarded of the 1993 Yrjö Jahnsson prize along with his colleague and collaborator Jean Tirole.

- Jean-Loup Chrétien, retired Général de Brigade (brigadier general) in the Armée de l'Air (French air force), and former CNES spationaut.

- Alain Carpentier, surgeon, who is given credit for the development of the first fully implantable artificial heart.

- Alfred A. Tomatis, prominent otolaryngologist and inventor.

- Catherine Cesarsky, astronomer and former president of the International Astronomical Union.

- Boris Cyrulnik, doctor, ethologist, neurologist, and psychiatrist.

- Alain Aspect, physicist, known for his works on Bell test experiments.

- Bernard Maris, economist, murdered on 7 January 2015, during the Charlie Hebdo shooting.

- Jérôme Rota, software developer, co-founder of DivX, Inc..

- Jacques Marescaux, surgeon, believed to be the first one in the world to operate a person without leaving a scar.

Artists

- Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 18th-century rococo painter and printmaker.

- Claude Joseph Vernet, 18th-century painter.

- Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 19th-century neoclassical painter.

- Auguste Renoir, 19th-century artist, one of the leading painter in the development of the Impressionist style.

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 19th-century post-impressionist painter, printmaker, draughtsman and illustrator.

- Rosa Bonheur, 19th-century realist painter.

- Frédéric Bazille, 19th-century impressionist painter.

- William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 19th-century academic painter.

- Odilon Redon, 19th-century symbolist painter, printmaker, draughtsman and pastellist.

- Alexandre Cabanel, 19th-century academic painter.

- Jean-Paul Laurens, 19th-century academic painter and sculptor.

- Honoré Daumier, printmaker, caricaturist, painter, and sculptor, whose many works offer commentary on social and political life in France in the 19th century.

- Paul Cézanne, 19th-century post-impressionist painter whose work laid the foundations of the transition from the 19th-century conception of artistic endeavour to a new and radically different world of art in the 20th century.

- Suzanne Valadon, 19th-century and early 20th-century.

- Arthur Batut, early 20th-century photographer and pioneer of aerial photography.

- Eugène Atget, early 20th-century photographer, regarded as one of the pioneer of documentary photography.

- Albert Marquet, 20th-century Fauvist painter.

- Aristide Maillol, 20th-century sculptor, painter and printmaker.

- Antoine Bourdelle, 20th-century sculptor, painter, and teacher.

- Yves Klein, 20th-century artist, considered an important figure in post-war European art.

- César, 20th-century sculptor and member of the Nouveau Réalisme.

- Arman, 20th-century painter, sculptor and printmaker, member of the Nouveau Réalisme.

- Lucien Clergue, photographer.

- Pierre Soulages, painter, engraver and sculptor.

- Sempé, cartoonist.

- Daniel Goossens, cartoonist.

Architects

- Guillaume Cammas, 18th-century painter and architect, author of the Capitole de Toulouse's facade.

- Jean-Baptiste Michel Vallin de la Mothe, who became Catherine II official court architect and mainly worked in Saint-Petersburg.

- Jean Nouvel, he obtained the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, the Wolf Prize in Arts in 2005 and the Pritzker Prize in 2008. Among his most acclaimed works, we can quote the Arab World Institute in Paris, the Torre Agbar in Barcelona or again the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

- Paul Andreu, famous for his designs of airports.

- Dominique Perrault, urban planner and architect, known for the design of the French National Library.

Musicians

- Jean-Joseph Mouret, composer from the Baroque era.

- André Campra, composer and conductor from the Baroque era.

- Jean-Joseph de Mondonville, 18th-century composer and violinist.

- Gabriel Fauré, 19th- and early 20th-century Post-romantic composer and organist.

- Déodat de Séverac, 19th- and early 20th-century Impressionist composer, influenced in his works by his native Languedoc.

- Emmanuel Chabrier, 19th-century Romantic composer.

- Marius Petipa, 19th-century influential ballet choreographer.

- Joseph Canteloube, 20th-century composer and musicologist.

- André Messager, 20th-century composer.

- Georges Auric, 20th-century composer. Member of Les Six.

- Darius Milhaud, 20th-century composer and teacher. Member of Les Six.

- Olivier Messiaen, 20th-century composer and organist.

- Michel Petrucciani, 20th-century jazz pianist.

- Chinese Man, trip hop band.

- David Fray, classical pianist.

- Maurice Béjart, choreographer and opera director.

- Alidé Sans

- Alonzo

- Marcel Amont, 20th-century French singer and Occitan-language songwriter.

- Ève Angeli

- Les Ablettes, 20th-century punk rock band.

- Thierry Amiel

- The Avener, DJ and music producer.

- Gilbert Bécaud, 20th-century singer.

- Priscilla Betti

- Guy Bonnet, 20th-century Occitan-language songwriter.

- Boulevard des Airs

- Georges Brassens, 20th-century songwriter, known for its poetic lyrics and using of black humor.

- Alan Braxe, electronic music artist.

- Francis Cabrel, 20th-century singer and songwriter.

- Cats on Trees

- Cécilia Cara

- Cocoon

- Collectif Métissé, Soma Riba

- Caroline Costa

- Lou Dalfin

- Emma Daumas

- Anne-Marie David, singer and winner of the 1973 Eurovision Song Contest.

- Rosina de Pèira

- Dionysos

- Diabologum

- DJ Fou

- Julien Doré, singer and songwriter.

- Pauline Ester, 20th-century singer.

- Eths

- Fabulous Trobadors

- Faf Larage

- fr:Fascagat

- Félicien Taris

- Fréro Delavega

- Gojira, heavy metal band.

- Gold

- Goulamas'k

- Gipsy Kings

- Hyphen Hyphen, electro-pop band.

- IAM, late 20th-century hip hop band.

- Images

- Imany

- Jean-Roch, influential DJ.

- oc:Joanda

- Jul

- Kaolin

- Marina Kaye

- Kazero

- Kid Wise

- Kungs

- La Femme, psych-punk rock band.

- La Mal Coiffée, occitan vocal band

- Jean-Jacques Lafon, 20th-century singer.

- Marie Laforêt, 20th-century singer.

- Francis Lalanne, 20th-century singer.

- Serge Lama, 20th-century singer.

- Boby Lapointe, 20th-century singer.

- M83, electro band.

- Jean-Pierre Mader, 20th-century singer.

- Christophe Maé, singer and songwriter.

- Mans de Breish, 20th-century Occitan-language songwriter.

- Mélissa Mars

- Massilia Sound System

- Mireille Mathieu, 20th-century singer.

- Møme

- Moos

- Jean-Louis Murat, singer and songwriter.

- Les Naufragés, Spi et la Gaudriole, folk band (ex-fr:OTH)

- Noir Désir, 20th-century rock band.

- Claude Nougaro, 20th-century singer and songwriter.

- Oai Star

- fr:OTH, 20th-century punk rock band.

- Patric, 20th-century Occitan-language songwriter.

- Panzer Flower, electro-pop band.

- Partenaire Particulier, electronic and new wave band

- Pierre Perret, 20th-century singer and songwriter.

- Stéphane Pompougnac, DJ and record producer.

- Sylvie Pullès

- Regg'Lyss

- Ringo, 20th-century singer.

- Dick Rivers, 20th-century singer.

- Olivia Ruiz

- Patrick Sébastien, 20th-century singer.

- Hélène Ségara, 20th-century singer.

- Jean Ségurel

- Émilie Simon, singer and composer of electronic music.

- Soko, singer and songwriter.

- Stille Volk

- Michèle Torr, 20th-century singer.

- Charles Trenet, 20th-century singer and songwriter.

- Wazoo

- Zebda

Statesmen, entrepreneurs and activists

- Richard I, 12th-century King of England, spent most of his life in Aquitaine and spoke Occitan language.

- Garsenda, 12th-century countess and trobairitz.

- Eleanor of Aquitaine, 12th-century Duchess of Aquitaine, Queen consort of France and later Queen consort of England, often regarded as one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

- Beatrice de Planissoles, Cathar minor noble.

- Richard II of England, 14th- century King of England who inspired Shakespeare's play.

- Francis I of France, 16th-century first King of France from the Angoulême branch who paved the way for the French Renaissance.

- Marguerite de Navarre, 16th-century princess of France and patron of Humanists and reformers. She is sometimes regarded as the "The First Modern Woman" due to her independence and important role in the spreading of the Renaissance in the French Kingdom.

- Jeanne d'Albret, 16th-century Queen regnant of Navarre and a key-figure of Protestantism in France.

- Henry IV of France, 16th-century King of France, known as Le Bon Roi Henri (Good King Henry), he remains one of the most emblematic King of France, notably for having been raised in the Protestant faith.

- Vincent de Paul, Roman Catholic priest who dedicated himself to serving the poor.

- Jean Nicot, diplomat and scholar who introduced snuff tobacco to the French royal court. The tobacco plant, Nicotiana,a flowering garden plant, was named after him by Carl Linnaeus, as was nicotine.

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson, explorer and fur trader, co-founder of the Hudson's Bay Company.

- Olympe de Gouges, 18th-century activist, known as one of the pioneer of Feminism.

- Louis de Bonald, 18th-century politician, a counter-revolutionary and conservator, known for his social theories that would later inspire Sociology.

- Paul Barras, main executive leader of the Directory regime.

- Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, leader of the early stages of the French revolution.

- Charles XIV John of Sweden (Jean Bernadotte), 19th-century Jacobines leader, Marshal of France, later King Charles XIV of Sweden and founder of the House of Bernadotte, the current royal family of Sweden.

- Louis Auguste Blanqui, socialist and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

- François Guizot, historian, orator and statesman, key figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848.

- Léon Gambetta, 19th-century Prime minister of France, a prominent political figure during and after the difficult period of the Franco-Prussian War, viewed as an humiliation by the French. He was also the proclaimer of the Third Republic.

- Bernadette Soubirous, Christian mystic and Saint. After her visions, Lourdes went on to become a major pilgrimage site.

- Charles Dupuy, 19th-century statesman, three times Prime Minister of France.

- Marie François Sadi Carnot, 19th-century statesman and fifth president of the Third Republic.

- Charles de Freycinet, early 20th-century statesman, four times Prime Minister of France.

- Théodore Steeg, 20th-century Radical politician.

- Armand Fallières, 20th-century statesman and president of the French republic from 1906 to 1913.

- Jean Jaurès, 20th-century statesman and one of the most important figure of the French Left.

- Émile Combes, statesman, who led the French Left political coalition Bloc des gauches's cabinet from June 1902 – January 1905.

- Gaston Doumergue, 20th-century statesman. He was the 13th President of France.

- Vincent Auriol, 20th-century French president. He was the first president of the Fourth Republic.

- André and Édouard Michelin, industrialists and founders of the Compagnie Générale des Établissements Michelin in 1888 in Clermont-Ferrand.

- Édouard Daladier, French Radical politician and Prime Minister of France at the start of the Second World War.

- François Darlan, 20th-century Prime minister of France during the pro-German Vichy regime.

- Jean Moulin, hero of the French resistance.

- Begum Om Habibeh Aga Khan, fourth and last wife of Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III.

- Jean Monnet, 20th-century political economist and diplomat. He is regarded by many as the chief architect of European unity and the founding father of the European Union.

- René Cassin, 1968 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948.

- Georges Pompidou, 20th-century French president.

- Jeanne Calment, supercentenarian who has the longest confirmed human lifespan on record.

- Henrik, Prince Consort of Denmark, husband of Queen Margrethe II.

- Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, 20th-century French president.

- Simone Veil, 20th-century lawyer and politician, survivor from the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, she is primary known as the mother of the law legalizing abortion in France on 17 January 1975.

- Jean-Luc Lagardère, founder and former CEO of the Lagardère Group.

- François Mitterrand, President of France from 1981 to 1995. He was therefore the longest-serving President of France and the first one from the Left under the Fifth Republic.

- Claude Bébéar, founder and former CEO of AXA.

- Bernard Kouchner, politician and physician, co-founder of Medecins Sans Frontiers.

- Michel Camdessus, applied economist and Managing Director of the IMF from 1987 to 2000, which makes him the longest serving Managing Director of this international institution.

- Lucien Barrière, heir and founder of the Lucien Barrière group.

- François Bayrou, leader of the centrist political party MoDem.

- Francis Bouygues, businessman and film producer, founder of Bouygues.

- Ives Roqueta, Occitan-language author and activist.

- Max Roqueta, Occitan-language activist, former president of the Institut d'études occitanes (Occitan research Institute).

- Daniel Cohn-Bendit, French-German politician.

Sport

- Bernard Laporte, rugby union coach and former French Secretary of State for Sport. He was head coach of the French national team and is currently the head coach at Rugby Club Toulonnais

- Claude Onesta, handball coach and responsible of France's Men's handball team since 2001. He has one of the most beautiful Handball coaching records with titles in major competitions such as The Olympics, The World Championship, and The European Championship.

- Claude Puel, current head coach of the OGC Nice

- Jean-Pierre Rives, former rugby player. "A cult figure in France," according to the BBC, he came to epitomise the team's spirit and "ultra-committed, guts-and-glory style of play. He was awarded the Order of the Legion of Honor and was inducted into the International Rugby Hall of Fame. He is one of the most emblematic rugby player of all time and described by Australian actor Hugh Jackman as "A small guy on the field, he finished every game with blood on face".

- Philippe Sella, former rugby player. An important figure of the French National team as well as the London Saracens. He later became a member of the International Rugby Hall of Fame in 1999 and the IRB Hall of Fame in 2008.

- Several rugby players members of the IRB Hall of Fame such as Jean Prat, Jo Maso and André Boniface as well as contemporary players like Yannick Jauzion, Fabien Pelous, William Servat, Cédric Heymans, Maxime Médard, Aurélien Rougerie, Dimitri Szarzewski, Yoann Huget and Hugo Bonneval.

- Adolphe Bousquet, two times Olympic medalist in rugby union.

- François Borde, Olympic medalist in rugby union.

- Several professional swimmers such as Olympic champions Camille Lacourt, Clément Lefert, Alain Bernard and Yannick Agnel.

- Renaud Lavillenie, pole vaulter, Olympic champion, and current world record holder.

- Tony Estanguet, slalom canoeist, multiple times Olympic gold medalist.

- Colette Besson, Olympic champion athlete.

- Nicole Duclos, athlete.

- Joseph Guillemot, Olympic champion long-distance runner.

- Stéphane Diagana, world champion athlete.

- Sébastien Ogier, rally driver and current holder of the World Rally Drivers' Championship.

- Nicolas Vouilloz, former rally driver.

- Gustave Garrigou, cyclist.

- Lucien Aimar, cyclist who won the 1966 Tour de France.

- Charles Coste, cyclist and Olympic medalist.

- Guillaume Néry, free-diver.

- Alain Giresse, retired international footballer and member of the Euro 84 winning team.

- Eric Cantona, former International footballer and important player of Manchester United F.C. in the mid-1990s.

- David Ginola, former international footballer.

- Zinedine Zidane, former international footballer.

- Laurent Blanc, former international footballer.

- Didier Deschamps, former international footballer.

- Vincent Candela, former international footballer.

- Fabien Barthez, former international footballer.

- Johan Micoud, former international footballer and member of the Euro 2000 winning team.

- Gaël Clichy, international footballer, he currently plays for Manchester City F.C..

- Philippe Mexès, international footballer, he currently plays for Milan.

- Samir Nasri, international footballer, he currently plays for Manchester City F.C..

- Mathieu Flamini, international footballer, he currently plays for Arsenal F.C..

- Aymeric Laporte, professional footballer, he currently plays for Athletic Bilbao.

- Blaise Matuidi, international footballer, he currently plays for Paris Saint-Germain.

- Lucas Hernández, international footballer, he currently plays for Atlético Madrid.

- Hugo Lloris, international footballer, he currently plays for Tottenham Hotspur F.C..

- Laurent Koscielny, international footballer, he currently plays for Arsenal F.C..

- Several handball players such as Xavier Barachet, Michaël Guigou, William Accambray, Théo Derot and Jérôme Fernandez.

- Richard Gasquet and Gilles Simon, tennis players.

- Thomas Heurtel, international basketball player from Anadolu Efes Istanbul.

- Louis François, Greco-Roman wrestler.

- Céline Dumerc, Sandrine Gruda and Paoline Salagnac, female basketball players.

- Yoann Jaumel, Earvin N'Gapeth, Pierre Pujol and Kévin Tillie, international volleyball players.

- Martin Fourcade, biathlete.

- Adrien Hardy, olympic medalist rower.

- Brigitte Guibal, olympic medalist slalom canoeer

- Marion Bartoli, former professional tennis player and winner of the 2013 Wimbledon Championships singles title.

- Pierre Jonquères d'Oriola and Christian d'Oriola, olympic medalists in fencing.

- Guy de Luget, olympic medalist in fencing.

- Dominique Sarron and Christian Sarron, Grand Prix motorcycle road racers.

- Gabriella Papadakis, ice dancer.

- Émilie Andéol, judoka.

- Martin Braud and Cédric Forgit, slalom canoer.

- Annie Famose, Alpine skier and Olympic medalist.

- Marielle Goitschel, Alpine skier and Olympic champion.

- Isabelle Delobel, ice dancer.

- François Gabart, professional offshore yacht racer who won the 2012-13 Vendée Globe.

- Audrey Prieto, female freestyle wrestler.

- Gauthier de Tessières, alpine ski racer.

- Claude Piquemal, athlete.

- Wilfrid Forgues, olympic medalist slalom canoeer.

- René Thomas, early 20th-century motor racing champion.

- Mathieu Crépel, professional snowboarder.

- Isabelle Blanc, snowboarder and Olympic champion.

- Erwann Le Péchoux, world champion in fencing.

- Marie-Laure Brunet, olympic biathlete.

- Xavier de Le Rue, big mountain snowboarder.

- Doriane Vidal, snowboarder and Olympic medalist.

- Pierre Vaultier, snowboarder and Olympic champion.

- Marie Marvingt, athlete, mountaineer, aviator and journalist.

- Johann Zarco, Grand Prix motorcycle racer.

- René Arnoux, motor racing driver.

- Joris Daudet, cyclist, 1997 and 2016 World Cup overall title winner in BMX.

- Cyril Abidi, kickboxer.

- Samy Schiavo, MMA fighter.

- Jules Bianchi, motor racing driver.

- Puig Aubert, prominent rugby league figure.

- Richard Tardits, former American football linebacker for the New England Patriots of the NFL.

- Boris Bede, Canadian football player.

- Bruce Bochy, former baseball player and current manager of the San Francisco Giants.

- Jehan Buhan, Olympic champion in foil competition.

- Jacques Lataste, two times Olympic champion in the team foil competition.

- Jean-Claude Magnan, Olympic champion in foil competition.

- Pascale Trinquet, Olympic champion in foil competition.

- Brigitte Latrille-Gaudin, Olympic champion in the team foil competition.

- Lionel Plumenail, Olympic champion in the team foil competition.

- Roger François, 1928 Olympic champion in weightlifting.

- Jean-Noël Ferrari, Olympic champion in the team foil competition.

- Guy Lapébie, cyclist, two times Olympic Champion in 4000m team pursuit and in Team road race.

- Arnaud Geyre, racing cyclist, Cycling at the men's team road race.

- Serge Maury, sailor, 1972 Olympic champion in the finn class.

- Gaston Aumoitte, Olympic champion in Croquet.

- Maurice Larrouy, Olympic champion in Shooting.

- Marguerite Broquedis, 1912 Olympic champion in tennis.

- Jean Boiteux, 1952 Olympic champion in freestyle swimming.

- Camille Muffat, 2012 Olympic champion in freestyle swimming.

- Henri Deglane, Olympic champion in Greco-Roman wrestling.

- Marie-Claire Restoux, 1996 Olympic champion in Judo.

- Boris Sanson, Olympic champion in team fencing.

- Nicolas Lopez, Olympic champion in team fencing.

- André Labatut, Olympic champion in the foil and épée competitions.

- René Bougnol, Olympic champion in the team foil event.

- Émile Coste, Olympic champion in the individual foil event.

- Pierre Durand, Jr., 1988 Olympic chammpion in equestrian individual jumping.

- Jean Teulère, Olympic champion in equestrian team eventing.

- Charles Coste, 1948 Olympic champion in team puruit.

- Fernand Decanali, 1948 Olympic champion in team pursuit.

- Frank Adisson, 1996 Olympic champion in slalom canoeing.

- Benoît Peschier, 2004 Olympic champion in slalom canoeing.

- Sébastien Vieilledent, Olympic champion in rowing.

- Michel Andrieux 2000 Olympic champion in rowing.

- Laurent Porchier, Olympic champion in rowing.

- Bernard Malivoire, Olympic champion in rowing.

- Virginie Dedieu, Olympic medalist in synchronized swimming.

- Jean-Philippe Gatien, Olympic silver medalist in table tennis.

- Astier Nicolas and Mathieu Lemoine, Olympic champion during the 2016 equestrian Team eventing.

- Denis Gargaud Chanut, Olympic champion in slalom canoeing.

- David Roumieu

Cinema

- Max Linder, 20th-century actor, director, screenwriter, producer and comedian of the silent film era.

- Louis Feuillade, 20th-century director of the silent film era.

- Fernandel, 20th-century actor and singer, who played in classic French, Italian and later American movies such as Paris Holiday or again Around the World in 80 Days.

- Charles Boyer, 20th-century actor who had a successful carrier at Holywood where he played in movies like The Garden of Allah along with actresses such as Marlene Dietrich and Hedy Lamarr.

- Robert Bresson, 20th-century film director and probably the most influential figure of the French New Wave.

- Éric Rohmer, 20th Century film director and one of the most important member of the French New Wave.

- Bernadette Lafont, actress, famous for her role in 1960s Nouvelle Vague movies.

- Henri Serre, Nouvelle Vague actor.

- René Clément, director and screenwriter.

- Simone Simon, actress.

- Simone Mareuil, actress, best known for her role in Luis Buñuel movie Un Chien Andalou.

- Maurice Pialat, film director and screenwriter.

- Louis Jourdan, film and television actor.

- Capucine, fashion model and actress.

- Danielle Darrieux, actress and pop icon who had a successful carrier at Holywood.

- André Cayatte, film director from the Nouvelle Vague who won two Golden Lions in 1950 and 1960.

- André Téchiné, film director from the late Nouvelle Vague who won the Best Director Award at Cannes Film Festival.

- Gérard Philipe, actor.

- Pierre Schoendoerffer, film director, screenwriter, writer, war reporter and war cameraman who won the Academy Award for Documentary Feature for The Anderson Platoon.

- Jean-Louis Trintignant, actor, screenwriter and film director.

- Édouard Molinaro, film director and screenwriter.

- Mireille Darc, actress and model.

- Jean-Claude Carrière, screenwriter, actor and Academy Award honoree.

- François Dupeyron, film director and screenwriter.

- Jean-Xavier de Lestrade, award-winning film director.

- Robert Guédiguian, film director, screenwriter, producer and actor.

- Jean Eustache, film director.

- Bertrand Bonello, film director, member of the New French Extremity movement

- Emmanuelle Béart, actress and model.

- Sandrine Bonnaire, actress, film director and screenwriter.

- Ariane Ascaride, actress and screenwriter.

- Audrey Tautou, actress and model, she achieved international recognition for her lead role in the 2001 film Amélie (2001), and later played in movies such as Stephen Frears's Dirty Pretty Things (2002) and Ron Howard's The Da Vinci Code (2006).

- Lou de Laâge, television, film and stage actress.

- Delphine Chanéac, model and actress.

- William Abadie, actor.

- Nicolas Cazalé, actor and model.

- Rémi Gaillard, famous YouTube prankster.

- Gilles Marini, actor.

- Mylène Jampanoï, actress.

Men of war and explorers

- Pytheas, Greek geographer from Massalia, who made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe in about 325 BC.

- Vercingetorix, chieftain of the Arverni tribe who fought against Roman forces during the last phase of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars at the Battle of Gergovia. He was probably born either in Gergovie or Nemossos (nowadays part of Clermont-Ferrand).

- Avitus, Western Roman Emperor from 8 or 9 July 455 to 17 October 456.

- Euric, King of the Visigoths from 466 until his death in 484.

- William II Sánchez of Gascony, Duke of Gascony from circa 961 at least until 996, he fought during the Reconquista. He is mainly known to have perpetrated a major defeat of the Vikings at Taller in 982.

- Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse, one of the leaders of the First Crusade.

- Mercadier, warrior and chief of mercenaries in service of Richard I, King of England.

- James I of Aragon, King of Aragon, Count of Barcelona, and Lord of Montpellier from 1213 to 1276; King of Majorca from 1231 to 1276; and Valencia from 1238 to 1276.

- Isabella of Angoulême, queen consort of England from 1200 until John's death in 1216.

- Jean Poton de Xaintrailles, minor noble who was appointed Marshal of France and who distinguished himself during the Hundred Years' War, notably at the Battle of Gerberoy.

- La Hire, major military commander of the late the Hundred Years' War and leader of the Battle of Patay.

- Jean III de Grailly, captal de Buch, one of the main commander of the Hundred Years' War who was attached to the English side.

- Gaston of Foix, Duke of Nemours, military commander who took brilliantly part in the War of the League of Cambrai.

- Jacques de La Palice, nobleman and military commander.

- Bayard, legendary soldier, sometimes known as "the knight without fear and beyond reproach".

- Pierre d'Aubusson, Grand Master of the order of St. John of Jerusalem and revered by all Christendom as "the Shield of the Church". He was the leader of the 1480 Siege of Rhodes attack.

- Louis des Balbes de Berton de Crillon, soldier, nicknamed the man without fear.

- Jean Parisot de la Valette, 49th Grand Master of the Order of Malta, from 21 August 1557 to his death in 1568. Knight Hospitaller, he joined the order in the Langue de Provence, he fought with distinction against the Turks at Rhodes. He commanded the resistance against the Ottomans at the Great Siege of Malta in 1565. Valletta, capital of Malta was named after him.

- Samuel de Champlain, navigator, cartographer, draughtsman, soldier, explorer, geographer, ethnologist, diplomat, and chronicler, considered as the "Father of New France".

- Jean-François Roberval, adventurer and first Lieutenant General of New France.

- Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons, merchant, explorer and colonizer who founded the first permanent French settlement in Canada.

- d'Artagnan, legendary captain of the Musketeers of the Guard who inspired Alexandre Dumas' d'Artagnan character.

- Armand d'Athos, Isaac de Porthau and Henri d'Aramitz, members of the Musketeers of the Guard who inspired Alexandre Dumas for his novel The Three Musketeers.

- Vicomte of Turenne, member of the Auvergnat La Tour d'Auvergne family, who distinguished himself during the battles of Nördlingen, Zusmarshausen, Turckheim and Dunes.

- Daniel Montbars, buccaneer, known as Montbars the Destroyer.

- Jean-Baptiste du Casse, buccaneer, admiral, and colonial administrator.

- Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, explorer and adventurer in New France, In 1701, he founded Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, the beginnings of modern Detroit, which he commanded until 1710. William H. Murphy and Henry M. Leland, founders of the Cadillac auto company in Detroit, paid homage to him by using his name for their company and his armorial bearings as its logo in 1902.

- Claude-Jean Allouez, Jesuit missionary and French explorer of North America, mainly Michigan and Wisconsin.

- Pierre Laclède, fur trader who, with his young assistant and stepson Auguste Chouteau, founded St. Louis in 1764.

- Marguerite Delaye, heroine of the Siege of Montelimar, during the French Wars of Religion.

- Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, commander of the forces in North America during the Seven Years' War, whose North American theatre is known as the French and Indian War in the United States.

- François Joseph Paul de Grasse, admiral, known for his command of the French fleet at the Battle of the Chesapeake, which led directly to the British surrender at Yorktown.

- Jean-François de La Pérouse, officer of the Royal French Navy. He was chosen by the Marquis de Castries and Louis XVI to lead an expedition around the world to complete James Cook discoveries in the Pacific Ocean. This maritime expedition mysteriously vanished, body and soul, at Vanikoro (Santa Cruz Islands) in 1788, three years after his departure from Brest. Numerous places were named after him, including the La Pérouse Strait between Russia and Japan.

- Nicolas-Louis d'Assas, captain of the Régiment d'Auvergne and hero of the Battle of Kloster Kampen.

- Lafayette, general and key figure of the American Revolutionary War. He was a close friend of George Washington. He is sometimes known as the Hero of the Two Worlds.

- John Ligonier, 1st Earl Ligonier, British soldier who became Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in 1757.

- Louis de Freycinet, navigator who published in 1811 the first map to show a full outline of the coastline of Australia.

- Guillaume Brune, Marshal of France who distinguished himself as Brigadier general during the late Revolutionary period battles of Castricum and Pozzolo.

- Jean Lafitte, French-American pirate and privateer in the Gulf of Mexico who took part in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans.

- Louis-René Levassor de Latouche Tréville, Vice-admiral who fought during the American Revolutionary War and under Napoleon during the Raids on Boulogne.

- Several Marshals of France of the Napoleonic Era, including Joachim Murat, Jean Lannes, Jean-Baptiste Bessières, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan or again André Masséna and Jean-de-Dieu Soult.

- Louis Desaix, general and military leader who distinguished himself during the Napoleonic Egyptian campaign.

- François Certain Canrobert, Marshal of France, one of the leader of the allied forces during the Crimean War, notably in the Battle of Inkerman and the Siege of Sevastopol.

- Pierre Bosquet, Marshal of France, who particularly served during the Crimean War and the conquest of Algeria.

- Thomas Robert Bugeaud, Marshal of France and Governor-General of Algeria primary remembered for his key role during the conquest of Algeria and the Battle of Isly.

- Jean-Joseph Ange d'Hautpoul, cavalry general of the Napoleonic wars.

- Jean Danjou, decorated captain who fought during the legendary Battle of Camarón.

- Abel Douay, general, killed in combat during the Battle of Wissembourg where the French defenders, although greatly outnumbered, fought heroically.

- Ferdinand Foch, Marshal of France, of Poland and of United Kingdom. Hero of the First World War, Addington says, "to a large extent the final Allied strategy which won the war on land in Western Europe in 1918 was Foch's alone."

- Joseph Joffre, general who served as Commander-in-Chief of French forces on the Western Front from the start of World War I until the end of 1916, best known for regrouping the retreating allied armies to defeat the Germans at the strategically decisive First Battle of the Marne in September 1914.

- Lionel de Marmier, World War I and II flying ace.

- Maryse Bastié, aviator and World War I pilot.

- Georges Bégué, engineer and agent in the Special Operations Executive during World War II.

Fashion

- Paul Iribe, illustrator and designer.

- Ted Lapidus, fashion designer.

- André Courrèges, fashion designer, primary remembered for its futuristic creations and his works at Balenciaga.

- Marcelle Auclair, co-founder of the fashion magazine Marie Claire.

- Christian Lacroix, fashion designer. His creations are often inspired by his native Camargue.

- Marithé + François Girbaud, fashion designers, known for their denim jeans.

- Emanuel Ungaro, fashion designer and founder of the House of Ungaro.

- Inès de la Fressange, model and arisocrat. She was named to the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1998.

- Christian Audigier, fashion designer.

- Cindy Bruna, model.

- Aymeline Valade, model.

- Sophie Theallet, fashion designer.

- Anais Mali, Victoria's Secret model.

- Isabelle Caro, model and actress.

Cooking

- Auguste Escoffier, chef, restaurateur and culinary writer who popularized and updated traditional French cooking methods.

- Alain Ducasse, chef.

- Pierre Gagnaire, chef.

- Michel Bras, chef.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Occitania. |

References

- ↑ Regional pronunciations: Occitània = [u(k)siˈtanjɔ, ukʃiˈtanjɔ, u(k)siˈtanja]. Note that the variant Occitania* = [utsitanˈi(j)ɔ] is considered incorrect, since it is influenced by French, according to Alibert's prescriptive grammar (p. viii) and to the prescriptions of the Occitan Language Council (p. 101).

- ↑ When speaking Occitan, Occitania can be easily referred to as lo país , i.e. 'the country'.

- ↑ Map of the Roman Empire, ca400 AD

- ↑ Map of the Visigothic Kingdom

- ↑ World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous People

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Juge (2001) Petit précis – Chronologie occitane – Histoire & civilisation, p. 14