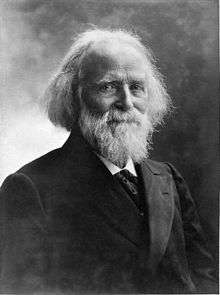

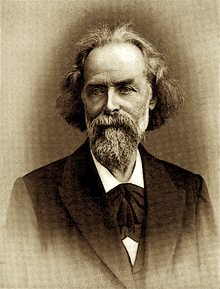

Élisée Reclus

| Élisée Reclus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

15 March 1830 Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, France |

| Died |

4 July 1905 (aged 75) Torhout, Belgium |

| Occupation | Geographer, anarchist revolutionary, and writer |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchist communism |

|---|

|

|

Concepts |

|

Organizational forms |

Jacques Élisée Reclus (French: [ʁəkly]; 15 March 1830 – 4 July 1905) was a renowned French geographer, writer and anarchist. He produced his 19-volume masterwork, La Nouvelle Géographie universelle, la terre et les hommes ("Universal Geography"), over a period of nearly 20 years (1875–1894). In 1892 he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Paris Geographical Society for this work, despite his having been banished from France because of his political activism.

Biography

Reclus was born at Sainte-Foy-la-Grande (Gironde). He was the second son of a Protestant pastor and his wife. From the family of fourteen children, several brothers, including fellow geographers Onésime and Élie Reclus, went on to achieve renown either as men of letters, politicians or members of the learned professions.

Reclus began his education in Rhenish Prussia, and continued higher studies at the Protestant college of Montauban. He completed his studies at University of Berlin, where he followed a long course of geography under Carl Ritter.

Withdrawing from France due to the political events of December 1851, he spent the next six years (1852–1857) traveling and working in Great Britain, the United States, Central America, and Colombia. Arriving in Louisiana in 1853, Reclus worked for about two and a half years as a tutor to the children of cousin Septime and Félicité Fortier at their plantation Félicité, located about 50 miles upriver from New Orleans. He recounted his passage through the Mississippi River Delta and impressions of antebellum New Orleans and the state in Fragment d'un voyage á Louisiane, published in 1855.[1]

On his return to Paris, Reclus contributed to the Revue des deux mondes, the Tour du monde and other periodicals, a large number of articles embodying the results of his geographical work. Among other works of this period was the short book Histoire d'un ruisseau, in which he traced the development of a great river from source to mouth. During 1867 and 1868, he published La Terre; description des phénomènes de la vie du globe in two volumes.

During the Siege of Paris (1870–1871), Reclus shared in the aerostatic operations conducted by Félix Nadar, and also served in the National Guard. As a member of the Association Nationale des Travailleurs, he published a hostile manifesto against the government of Versailles in support of the Paris Commune of 1871 in the Cri du Peuple.

Continuing to serve in the National Guard, which was then in open revolt, Reclus was taken prisoner on 5 April. On 16 November he was sentenced to deportation for life. Because of intervention by supporters from England, the sentence was commuted in January 1872 to perpetual banishment from France.

After a short visit to Italy, Reclus settled at Clarens, Switzerland, where he resumed his literary labours and produced Histoire d'une montagne, a companion to Histoire d'un ruisseau. There he wrote nearly the whole of his work, La Nouvelle Géographie universelle, la terre et les hommes, "an examination of every continent and country in terms of the effects that geographic features like rivers and mountains had on human populations—and vice versa,"[2] This compilation was profusely illustrated with maps, plans, and engravings. It was awarded the gold medal of the Paris Geographical Society in 1892. An English edition appeared simultaneously, also in 19 volumes, the first four by translated E. G. Ravenstein, the rest by A. H. Keane. Reclus's writings were characterized by extreme accuracy and brilliant exposition, which gave them permanent literary and scientific value.

According to Kirkpatrick Sale:[2]

His geographical work, thoroughly researched and unflinchingly scientific, laid out a picture of human-nature interaction that we today would call bioregionalism. It showed, with more detail than anyone but a dedicated geographer could possibly absorb, how the ecology of a place determined the kinds of lives and livelihoods its denizens would have and thus how people could properly live in self-regarding and self-determined bioregions without the interference of large and centralized governments that always try to homogenize diverse geographical areas.

In 1882, Reclus initiated the Anti-Marriage Movement. In accordance with these beliefs, he and his wife allowed their two daughters to "marry" without any civil or religious ceremony, an action causing embarrassment to many of his well-wishers. The French government initiated prosecution from the High Court of Lyon against the anarchists and members of the International Association, of which Reclus and the influential Peter Kropotkin were designated the two chief organizers. Kropotkin was arrested and condemned to five years' imprisonment, but Reclus escaped punishment as he remained in Switzerland.[3]

In 1894, Reclus was appointed chair of comparative geography at the University of Brussels, and moved with his family to Belgium. His brother Élie Reclus was at the university already teaching religion.[3] Élisée Reclus continued to write, contributing several important articles and essays to French, German and English scientific journals. He was awarded the 1894 Patron's Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.[4]

In 1905, shortly before his death, Reclus completed L'Homme et la terre, in which he rounded out his previous works by considering humanity's development relative to its geographical environment.[5]

Personal life

Reclus married and had a family, including two daughters.

He died at Torhout, near Bruges, Belgium.

Legacy

Reclus was admired by many prominent 19th century thinkers, including Alfred Russel Wallace,[6] George Perkins Marsh and Patrick Geddes,[7] Henry Stephens Salt,[8] and Octave Mirbeau.[9] James Joyce was influenced by Reclus' book La civilisation et les grands fleuves historiques.

Reclus advocated nature conservation and opposed meat-eating and cruelty to animals. He was a vegetarian.[10] As a result, his ideas are seen by some historians and writers as anticipating the modern social ecology and animal rights movements.[11][12]

Works

L'Homme et la terre ("The Earth and its Inhabitants"), 6 volumes:

- Élisée Reclus (1876–1894), A.H. Keane, ed., The Earth and its Inhabitants, London: Virtue & Co.

- Elisée Reclus (1890). The Earth and Its Inhabitants. D. Appleton and Company.

- Élisée Reclus (1883–1893), The Earth and its Inhabitants, New York: D. Appleton, OCLC 6631001

- The earth and its inhabitants. The universal geography, ed. by E.G. Ravenstein (A.H. Keane). (J.S. Virtue, 1878)

- The earth and its inhabitants, Asia, Volume 1 (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

- The Earth and Its Inhabitants ...: Asiatic Russia: Caucasia, Aralo-Caspian basin, Siberia' (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

- The Earth and Its Inhabitants ...: South-western Asia (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

- Anthology

- Du sentiment de la nature dans les sociétés modernes et autres textes, Éditions Premières Pierres, 2002 – ISBN 9782913534049

Articles

- "The Progress of Mankind" (Contemporary Review, 1896)

- "Attila de Gerando" (Revue Géographie, 1898)

- "A Great Globe", Geograph. Journal, 1898

- "L'Extrême-Orient" (Bulletin Antwerp Géographie Sociétie, 1898), a study of the political geography of the Far East and its possible changes

- Elisée Reclus (1867). La Guerre du Paraguay. Revue des Deux Mondes.

- A report made for parisian newspapers about the Paraguayan War, sympathetic towards the Paraguayan side.

- "La Perse" (Bulletin Sociétie Neuchateloise, 1899)

- "La Phénice et les Phéniciens" (ibid., 1900)

- "La Chine et la diplomatie européenne" (L'Humanité nouvelle series, 1900)

- "L'Enseignement de la géographie" (Institute Géographie de Bruxelles, No 5, 1901)

Books

- L'Homme et la terre (1905), e-text online, Internet Archive

See also

References

- ↑ Clark, John. "Putting Freedom on the Map: The Life and Work of Élisée Reclus (Introduction and translation of Fragment)". Mesechabe. 11 (Winter 1993): 14–17. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- 1 2 Sale, Kirkpatrick (2010-07-01) Are Anarchists Revolting?, The American Conservative

- 1 2 Ingeborg Landuyt and Geert Lernout, "Joyce's Sources: Les Grands Fleuves Historiques", originally published in Joyce Studies, Annual 6 (1995): 99–138

- ↑ "List of Past Gold Medal Winners" (PDF). Royal Geographical Society. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ Élisée Reclus, L'Homme et la terre (1905), e-text, Internet Archive

- ↑ Wallace, A. R. (1905). My Life: A Record of Events and Opinions. Chapman and Hall. OCLC 473067997.

- ↑ Livingstone, David N. (1993). The Geographical Tradition: Episodes in the History of a Contested Enterprise. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18535-6. OCLC 25787010.

- ↑ "Are we to apply the name "crank" to that great thinker and beautiful writer, Elisee Reclus? One of the finest essays ever written in praise of vegetarianism is an article which he contributed to the Humane Review when I was editing it in 1901."Salt, Henry Stephens (1930). Company I have kept. George Allen & Unwin. p. 162. OCLC 2113916.

- ↑ "...the scales were finally tipped...by Mirbeau's contact with the works of Kropotkin, Reclus and Tolstoy....They were the compound catalyst which caused Mirbeau's own ideas to crystallise, and they constituted a trilogy of enduring influences."Reg Carr, Anarchism in France: The Case of Octave Mirbeau Manchester University Press, 1977.

- ↑ "History of Vegetarianism – Élisée Reclus (1830 – 1905)". ivu.org. International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ↑ Marshall, Peter (1993). "Élisée Reclus: The Geographer of Liberty". Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Fontana. ISBN 0-00-686245-4. OCLC 490216031.

- ↑ JON HOCHSCHARTNER, Elisee Reclus - The Vegetarian Communard, CounterPunch, 2014.03.19

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Reclus, Jean Jacques Elisée". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 957,958.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Reclus, Jean Jacques Elisée". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 957,958.

Further reading

- "Élisée Reclus, savant et anarchiste". Cahiers Pensée et Action. Paris -Bruxelles. 1956.

- Brun, Christophe (2015), Élisée Reclus, une chronologie familiale, 1796-2015, 440 p., illustrations, tableaux généalogiques, documents. , .

- The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists and Secret Police by Alex Butterworth (Pantheon Books, 2010)

- Clark, John P. (1997). "The Dialectical Social Geography of Élisée Reclus". In Light, Andrew; Smith, Jonathan M. Philosophy and Geography 1: Space, Place, and Environmental Ethics. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 117–142.

- Cornuault, Joël (1995). Élisée Reclus, géographe et poète. Eglise-Neuve d'Issac: Éditions fédérop.

- Cornuault, Joël (1999). Élisée Reclus, étonnant géographe. Périgueux: Fanlac.

- Cornuault, Joël (2005). Élisée Reclus et les Fleurs Sauvages. Bergerac: Librairie La Brèche.

- Cornuault, Joël (1996–2006). Les Cahiers Élisée Reclus. Bergerac: Librairie La Brèche.

- Dunbar, Gary S. (1978). Elisée Reclus; A Historian of Nature. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books.

- Ferretti, Federico (2007). Il mondo senza la mappa: Elisée Reclus e i Geografi Anarchici. Milano: Zero in condotta.

- Ferretti, Federico (2010). "Comment Elisée Reclus est devenu athée: un nouveau document biographique". Cybergeo, European Journal of Geography.

- Ferretti, Federico (2011). "The correspondence between Élisée Reclus and Pëtr Kropotkin as a source for the history of geography". Journal of Historical Geography. 37 (2): 216–222. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2010.10.001.

- Ferretti, Federico (2012). Elisée Reclus, lettres de prison et d'exil. Lardy.

- Ferretti, Federico (2013). ""They have the right to throw us out": Élisée Reclus' New Universal Geography". Antipode. 1 (45). doi:10.1111/anti.12006.

- Fleming, Marie (1979). The Anarchist Way of Socialism. Totowa, N.J., USA: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Fleming, Marie (1988). The Geography of Freedom: the Odyssey of Élisée Reclus. Montréal: Black Rose Books.

- Gonot, Roger (1996). Élisée Reclus, Prophète de l'idéal anarchiste. Covedi.

- Ishill, Joseph (1927). Élisée and Élie Reclus. Berkeley Heights, New Jersey: The Oriole Press.

- Kropotkin P. A. Obituary. Elisée Reclus // Geographical Journal. 1905. Vol. 26, № 3, Sept. P. 337-343; Obituary. Elisée Reclus. London, 1905. 8 p.

- Lamaison, Crestian (2005). Élisée Reclus, l'Orthésien qui écrivait la Terre. Orthez: Cité du Livre.

- Pelletier, Philippe (2005). "La géographie innovante d'Élisée Reclus". Les Amis de Sainte-Foy et sa Région. 86 (2): 7–38.

- Philippe Pelletier, Elisée Reclus, géographie et anarchie, Paris, Editions du monde Libertaire, 2009.

- Sarrazin, Hélène (1985). Élisée Reclus ou la passion du monde. Paris: La Découverte.

- Springer, Simon, Anarchism! What Geography Still Ought to Be", Antipode, 2012.

- Springer, Simon, Anarchism and geography: a brief genealogy of anarchist geographies", Geography Compass, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Élisée Reclus. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Élisée Reclus |

- Élisée Reclus, Research on Anarchism

- Élisée Reclus entry at the Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia

- Élisée Reclus entry at the Anarchy Archives

- Samuel Stephenson, "Jacques Elisée Reclus (15 March 1830 – 4 July 1905)", Reed College

- Ingeborg Landuyt and Geert Lernout, "Joyce's Sources: Les Grands Fleuves Historiques", originally published in Joyce Studies, Annual 6 (1995): 99-138.

- Élisée Reclus, "An Anarchist on Anarchy" (1884)

- Works by Elisée Reclus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Élisée Reclus at Internet Archive