Nagasaki

| Nagasaki 長崎市 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core city | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

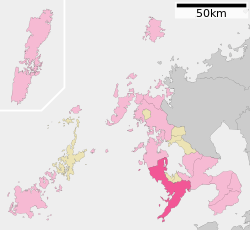

Map of Nagasaki Prefecture with Nagasaki highlighted in pink | |||||||

Nagasaki

| |||||||

| Coordinates: 32°47′N 129°52′E / 32.783°N 129.867°ECoordinates: 32°47′N 129°52′E / 32.783°N 129.867°E | |||||||

| Country | Japan | ||||||

| Region | Kyushu | ||||||

| Prefecture | Nagasaki Prefecture | ||||||

| District | n/a | ||||||

| Government | |||||||

| • Mayor | Tomihisa Taue (2007-) | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

| • Total | 406.35 km2 (156.89 sq mi) | ||||||

| • Land | 241.20 km2 (93.13 sq mi) | ||||||

| • Water | 165.15 km2 (63.76 sq mi) | ||||||

| Population (January 1, 2009) | |||||||

| • Total | 446,007 | ||||||

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (3,000/sq mi) | ||||||

| Time zone | Japan Standard Time (UTC+9) | ||||||

| - Tree | Chinese tallow tree | ||||||

| - Flower | Hydrangea | ||||||

| Phone number | 095-825-5151 | ||||||

| Address |

2-22 Sakura-machi, Nagasaki-shi, Nagasaki-ken 850-8685 | ||||||

| Website |

www | ||||||

Nagasaki (長崎市 Nagasaki-shi) (![]() listen ) is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan. It became a centre of Portuguese and Dutch influence in the 16th through 19th centuries, and the Churches and Christian Sites in Nagasaki have been proposed for inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Part of Nagasaki was home to a major Imperial Japanese Navy base during the First Sino-Japanese War and Russo-Japanese War. Its name means "long cape".

listen ) is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan. It became a centre of Portuguese and Dutch influence in the 16th through 19th centuries, and the Churches and Christian Sites in Nagasaki have been proposed for inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Part of Nagasaki was home to a major Imperial Japanese Navy base during the First Sino-Japanese War and Russo-Japanese War. Its name means "long cape".

During World War II, the American atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made Nagasaki the second and, to date, last city in the world to experience a nuclear attack.[1]

As of 1 January 2009, the city has an estimated population of 446,007 and a population density of 1,100 persons per km². The total area is 406.35 km².

History

Medieval and early modern history

A small fishing village set in a secluded harbor, Nagasaki had little historical significance until contact with Portuguese explorers in 1543. An early visitor was Fernão Mendes Pinto, who came on a Portuguese ship which landed nearby in Tanegashima.

Soon after, Portuguese ships started sailing to Japan as regular trade freighters, thus increasing the contact and trade relations between Japan and the rest of the world, and particularly with mainland China, with whom Japan had previously severed its commercial and political ties, mainly due to a number of incidents involving Wokou piracy in the South China Sea, with the Portuguese now serving as intermediaries between the two Asian countries.

Despite the mutual advantages derived from these trading contacts, which would soon be acknowledged by all parties involved, the lack of a proper seaport in Kyūshū for the purpose of harboring foreign ships posed a major problem for both merchants and the Kyushu daimyo (feudal lords) who expected to collect great advantages from the trade with the Portuguese.

In the meantime, Navarrese Jesuit missionary St. Francis Xavier arrived in Kagoshima, South Kyūshū, in 1549, and soon initiated a thorough campaign of evangelization throughout Japan, but left for China in 1551 and died soon afterwards. His followers who remained behind converted a number of daimyo. The most notable among them was Ōmura Sumitada. In 1569, Ōmura granted a permit for the establishment of a port with the purpose of harboring Portuguese ships in Nagasaki, which was finally set up in 1571, under the supervision of the Jesuit missionary Gaspar Vilela and Portuguese Captain-Major Tristão Vaz de Veiga, with Ōmura's personal assistance.[2]

.jpg)

The little harbor village quickly grew into a diverse port city , and Portuguese products imported through Nagasaki (such as tobacco, bread, textiles and a Portuguese sponge-cake called castellas) were assimilated into popular Japanese culture. Tempura derived from a popular Portuguese recipe originally known as peixinho-da-horta, and takes its name from the Portuguese word, 'tempero' another example of the enduring effects of this cultural exchange. The Portuguese also brought with them many goods from China.

Due to the instability during the Sengoku period, Sumitada and Jesuit leader Alexandro Valignano conceived a plan to pass administrative control over to the Society of Jesus rather than see the Catholic city taken over by a non-Catholic daimyo. Thus, for a brief period after 1580, the city of Nagasaki was a Jesuit colony, under their administrative and military control. It became a refuge for Christians escaping maltreatment in other regions of Japan.[3] In 1587, however, Toyotomi Hideyoshi's campaign to unify the country arrived in Kyūshū. Concerned with the large Christian influence in southern Japan, as well as the active and what was perceived as the arrogant role the Jesuits were playing in the Japanese political arena, Hideyoshi ordered the expulsion of all missionaries, and placed the city under his direct control. However, the expulsion order went largely unenforced, and the fact remained that most of Nagasaki's population remained openly practicing Catholic.

In 1596, the Spanish ship San Felipe was wrecked off the coast of Shikoku, and Hideyoshi learned from its pilot[4] that the Spanish Franciscans were the vanguard of an Iberian invasion of Japan. In response, Hideyoshi ordered the crucifixions of twenty-six Catholics in Nagasaki on February 5 of that year (i.e. the "Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan"). Portuguese traders were not ostracized, however, and so the city continued to thrive.

In 1602, Augustinian missionaries also arrived in Japan, and when Tokugawa Ieyasu took power in 1603, Catholicism was still tolerated. Many Catholic daimyo had been critical allies at the Battle of Sekigahara, and the Tokugawa position was not strong enough to move against them. Once Osaka Castle had been taken and Toyotomi Hideyoshi's offspring killed, though, the Tokugawa dominance was assured. In addition, the Dutch and English presence allowed trade without religious strings attached. Thus, in 1614, Catholicism was officially banned and all missionaries ordered to leave. Most Catholic daimyo apostatized, and forced their subjects to do so, although a few would not renounce the religion and left the country for Macau, Luzon and Japantowns in Southeast Asia. A brutal campaign of persecution followed, with thousands of converts across Kyūshū and other parts of Japan killed, tortured, or forced to renounce their religion (see Martyrs of Japan).

Catholicism's last gasp as an open religion, and the last major military action in Japan until the Meiji Restoration, was the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637. While there is no evidence that Europeans directly incited the rebellion, Shimabara Domain had been a Christian han for several decades, and the rebels adopted many Portuguese motifs and Christian icons. Consequently, in Tokugawa society the word "Shimabara" solidified the connection between Christianity and disloyalty, constantly used again and again in Tokugawa propaganda.

The Shimabara Rebellion also convinced many policy-makers that foreign influences were more trouble than they were worth, leading to the national isolation policy. The Portuguese, who had been previously living on a specially constructed island-prison in Nagasaki harbour called Dejima, were expelled from the archipelago altogether, and the Dutch were moved from their base at Hirado into the trading island. In 1720 the ban on Dutch books was lifted, causing hundreds of scholars to flood into Nagasaki to study European science and art. Consequently, Nagasaki became a major center of rangaku, or "Dutch Learning". During the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate governed the city, appointing a hatamoto, the Nagasaki bugyō, as its chief administrator.

Consensus among historians was once that Nagasaki was Japan's only window on the world during its time as a closed country in the Tokugawa era. However, nowadays it is generally accepted that this was not the case, since Japan interacted and traded with the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Korea and Russia through Satsuma, Tsushima and Matsumae respectively. Nevertheless, Nagasaki was depicted in contemporary art and literature as a cosmopolitan port brimming with exotic curiosities from the Western World.[5]

In 1808, during the Napoleonic Wars the Royal Navy frigate HMS Phaeton entered Nagasaki Harbor in search of Dutch trading ships. The local magistrate was unable to resist the British demand for food, fuel, and water, later committing seppuku as a result. Laws were passed in the wake of this incident strengthening coastal defenses, threatening death to intruding foreigners, and prompting the training of English and Russian translators.

The Tōjinyashiki (唐人屋敷) or Chinese Factory in Nagasaki was also an important conduit for Chinese goods and information for the Japanese market. Various colourful Chinese merchants and artists sailed between the Chinese mainland and Nagasaki. Some actually combined the roles of merchant and artist such as 18th century Yi Hai. It is believed that as much as one-third of the population of Nagasaki at this time may have been Chinese.[6]

Modern history

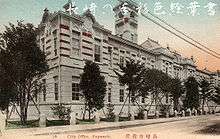

With the Meiji Restoration, Japan opened its doors once again to foreign trade and diplomatic relations. Nagasaki became a free port in 1859 and modernization began in earnest in 1868. Nagasaki was officially proclaimed a city on April 1, 1889. With Christianity legalized and the Kakure Kirishitan coming out of hiding, Nagasaki regained its earlier role as a center for Roman Catholicism in Japan.

During the Meiji period, Nagasaki became a center of heavy industry. Its main industry was ship-building, with the dockyards under control of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries becoming one of the prime contractors for the Imperial Japanese Navy, and with Nagasaki harbor used as an anchorage under the control of nearby Sasebo Naval District. During World War II, at the time of the nuclear attack, Nagasaki was an important industrial city, containing both plants of the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, the Akunoura Engine Works, Mitsubishi Arms Plant, Mitsubishi Electric Shipyards, Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works, several other small factories, and most of the ports storage and trans-shipment facilities, which employed about 90% of the city's labor force, and accounted for 90% of the city's industry. These connections with the Japanese war effort made Nagasaki a major target for strategic bombing by the Allies during the war.[7][8]

Atomic bombing of Nagasaki during World War II

For 12 months prior to the nuclear attack, Nagasaki had experienced five small-scale air attacks by an aggregate of 136 U.S. planes which dropped a total of 270 tons of high explosive, 53 tons of incendiary, and 20 tons of fragmentation bombs. Of these, a raid of August 1, 1945, was most effective, with few of the bombs hitting the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, several hitting the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, and six bombs landing at the Nagasaki Medical School and Hospital, with three direct hits on buildings there. While the damage from these few bombs was relatively small, it created considerable concern in Nagasaki and a number of people, principally school children, were evacuated to rural areas for safety, thus reducing the population in the city at the time of the atomic attack.[7][9][10][11]

On the day of the nuclear strike, the population in Nagasaki was estimated to be 263,000, which consisted of 240,000 Japanese residents, 10,000 Korean residents, 2,500 conscripted Korean workers, 9,000 Japanese soldiers, 600 conscripted Chinese workers, and 400 Allied POWs.[11] That day, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Bockscar, commanded by Major Charles Sweeney, departed from Tinian's North Field just before dawn, this time carrying a plutonium bomb, code named "Fat Man". The primary target for the bomb was Kokura, with the secondary target, Nagasaki, if the primary target was too cloudy to make a visual sighting. When the plane reached Kokura at 9:44 a.m. (10:44 a.m. Tinian Time), the city was obscured by clouds and smoke, as the nearby city of Yawata had been firebombed on the previous day. Unable to make a bombing attack on visual due to the clouds and smoke and with limited fuel, the plane left the city at 10:30 a.m. for the secondary target. After 20 minutes, the plane arrived at 10:50 a.m. over Nagasaki, but the city was also concealed by clouds. Desperately short of fuel and after making a couple of bombing runs without obtaining any visual target, the crew was forced to use radar in order to drop the bomb. At the last minute, the opening of the clouds allowed them to make visual contact with a racetrack in Nagasaki, and they dropped the bomb on the city's Urakami Valley midway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south, and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works in the north.[12] After 53 seconds of its release, the bomb exploded at 11:02 a.m. at an approximate altitude of 1,800 feet.[13]

Within less than a second after the detonation, the north of the city was destroyed and 35,000 people were killed.[14] Among the deaths were 6,200 out of the 7,500 employees of the Mitsubishi Munitions plant, and 24,000 others (including 2,000 Koreans) who worked in other war plants and factories in the city, as well as 150 Japanese soldiers. The industrial damage in Nagasaki was high, leaving 68–80% of the non-dock industrial production destroyed. It was the second and, to date, the last use of a nuclear weapon in combat, and also the second detonation of a plutonium bomb. The first combat use of a nuclear weapon was the "Little Boy" bomb, which was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the first plutonium bomb was tested in central New Mexico, United States, on July 16, 1945. The Fat Man bomb was somewhat more powerful than the one dropped over Hiroshima, but because of Nagasaki's more uneven terrain, there was less damage.[15][16][17][18]

After the war

The city was rebuilt after the war, albeit dramatically changed. The pace of reconstruction was slow. The first simple emergency dwellings were not provided until 1946. The focus on redevelopment was the replacement of war industries with foreign trade, shipbuilding and fishing. This was formally declared when the Nagasaki International Culture City Reconstruction Law was passed in May 1949.[19] New temples were built, as well as new churches owing to an increase in the presence of Christianity.[20] Some of the rubble was left as a memorial, such as a one-legged torii at Sannō Shrine and an arch near ground zero. New structures were also raised as memorials, such as the Atomic Bomb Museum. Nagasaki remains first and foremost a port city, supporting a rich ship building industry and setting a strong example of perseverance and peace.

On January 4, 2005, the towns of Iōjima, Kōyagi, Nomozaki, Sanwa, Sotome and Takashima (all from Nishisonogi District) were officially merged into Nagasaki.

Geography and climate

Nagasaki and Nishisonogi Peninsulas are located within the city limits. The city is surrounded by the cities of Isahaya and Saikai, and the towns of Togitsu and Nagayo in Nishisonogi District.

Nagasaki lies at the head of a long bay which forms the best natural harbor on the island of Kyūshū. The main commercial and residential area of the city lies on a small plain near the end of the bay. Two rivers divided by a mountain spur form the two main valleys in which the city lies. The heavily built-up area of the city is confined by the terrain to less than 4 square miles (10 km2).

Nagasaki has the typical humid subtropical climate of Kyūshū and Honshū, characterized by mild winters and long, hot, and humid summers. Apart from Kanazawa and Shizuoka it is the wettest sizeable city in Japan and indeed all of temperate Eurasia. In the summer, the combination of persistent heat and high humidity results in unpleasant conditions, with wet-bulb temperatures sometimes reaching 26 °C (79 °F). In the winter, however, Nagasaki is drier and sunnier than Gotō to the west, and temperatures are slightly milder than further inland in Kyūshū. Since records began in 1878 the wettest month has been July 1982 with 1,178 millimetres (46 in) including 555 millimetres (21.9 in) in a single day, whilst the driest month has been September 1967 with 1.8 millimetres (0.07 in). Precipitation occurs year-round, though winter is the driest season; rainfall peaks sharply in June & July. August is the warmest month of the year. On January 24, 2016, a snowfall of 17 centimetres (6.7 in) was recorded.[21]

| Climate data for Nagasaki, Nagasaki (1981~2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.3 (70.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

29.0 (84.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

37.6 (99.7) |

36.1 (97) |

33.7 (92.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

37.7 (99.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

28.6 (83.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.8 (73) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

24.8 (76.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

17.2 (63) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.0 (68) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

16.1 (61) |

10.8 (51.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

13.9 (57) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.2 (22.6) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.9 (48) |

15.0 (59) |

17.0 (62.6) |

11.1 (52) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−3.9 (25) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 64.0 (2.52) |

85.7 (3.374) |

132.0 (5.197) |

151.3 (5.957) |

179.3 (7.059) |

314.6 (12.386) |

314.4 (12.378) |

195.4 (7.693) |

188.8 (7.433) |

85.8 (3.378) |

85.6 (3.37) |

60.8 (2.394) |

1,857.7 (73.139) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 2 (0.8) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

4 (1.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.5 mm) | 11.1 | 9.9 | 12.5 | 10.8 | 10.6 | 13.5 | 11.6 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 6.2 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 124.7 |

| Average snowy days | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 64 | 66 | 68 | 72 | 79 | 80 | 75 | 73 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 70 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 102.8 | 119.7 | 148.5 | 174.7 | 184.4 | 135.3 | 178.7 | 210.7 | 172.8 | 181.4 | 137.9 | 119.1 | 1,866 |

| Source #1: Japan Meteorological Agency[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Japan Meteorological Agency (records)[23] | |||||||||||||

Education

Universities

- Nagasaki University

- Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science

- Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies[24]

- Kwassui Women's College

- Nagasaki Junshin University

- Siebold University of Nagasaki

Junior colleges

- Nagasaki Junior College

- Nagasaki Junshin Women's Junior College

- Tamaki Women's Junior College (玉木女子短期大学)

- Nagasaki Women's Junior College (長崎女子短期大学)

Transportation

The nearest airport is Nagasaki Airport in the nearby city of Ōmura. The Kyushu Railway Company (JR Kyushu) provides rail transportation on the Nagasaki Main Line, whose terminal is at Nagasaki Station. In addition, the Nagasaki Electric Tramway operates five routes in the city. The Nagasaki Expressway serves vehicular traffic with interchanges at Nagasaki and Susukizuka. In addition, six national highways crisscross the city: Routes 34, 202, 251, 324, and 499.

Sports

Nagasaki is represented in the J. League of football with its local club, V-Varen Nagasaki.

Main sites

- Confucius Shrine

- Dejima Museum of History

- Former residence of Shuhan Takashima

- Former site of Latin Seminario

- Former site of the British Consulate in Nagasaki

- Former site of Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Nagasaki Branch

- Glover Garden

- Former Glover Residence

- Former Alt Residence

- Former Ringer Residence

- Former Walker Residence

- Fukusai-ji

- Gunkanjima

- Higashi-Yamate Juniban Mansion

- Kazagashira Park

- Kōfuku-ji

- Megane Bridge

- Mount Inasa

- Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum[25] (Located next to the Peace Park)

- Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture[26]

- Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

- Nagasaki Peace Park

- Atomic Bomb Hypocenter (Located near the Peace Park)

- Nagasaki Peace Pagoda

- Nagasaki Penguin Aquarium[27]

- Nagasaki Chinatown

- Nagasaki Science Museum[27]

- Nagasaki Subtropical Botanical Garden

- Nyoko-do Hermitage

- Ōura Church

- Sannō Shrine - One-legged stone torii, sometimes called an arch or gateway

- Sakamoto International Cemetery

- Shōfuku-ji

- Siebold Memorial Museum

- Sōfuku-ji - Daiyūhōden and Daiippomon are national treasures of Japan.

- Suwa Shrine

- Syusaku Endo Literature Museum

- Tateyama Park

- Twenty-Six Martyrs Museum and Monument

- Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum

- Urakami Cathedral

- Miyo-Ken, a temple where the white snake is worshiped[28]

-

Monument at the atomic bomb hypocenter in Nagasaki

-

Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

-

Sōfuku-ji (National treasure of Japan)

Events

The Prince Takamatsu Cup Nishinippon Round-Kyūshū Ekiden, the world's longest relay race, begins in Nagasaki each November.

Kunchi, the most famous festival in Nagasaki, is held from 7–9 October.

The Nagasaki Lantern Festival,[29] celebrating the Chinese New Year, is celebrated from February 18 to March 4.

Cuisine

- Champon

- Sara udon

- Mogi Biwa

- Kasutera

- Chinese Confections

- Urakami Soboro

- Shippoku Cuisine

- Toruko rice (Turkish rice)

- Karasumi

- Nagasaki Kakuni Manju

Twin towns

The city of Nagasaki maintains sister cities or friendship relations with other cities worldwide.[30]

Hiroshima, Japan

Hiroshima, Japan Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States, since 1955[30]

Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States, since 1955[30] Dupnitsa, Bulgaria

Dupnitsa, Bulgaria Santos, Brazil, since 1972[30]

Santos, Brazil, since 1972[30] Fuzhou, China, since 1980[30]

Fuzhou, China, since 1980[30] Middelburg, Netherlands, since 1978[30]

Middelburg, Netherlands, since 1978[30] Porto, Portugal, since 1978[30][31]

Porto, Portugal, since 1978[30][31] Vaux-sur-Aure, France, since 2005; sister city of Sotome since 1978[30]

Vaux-sur-Aure, France, since 2005; sister city of Sotome since 1978[30]

See also

- Cultural treatments of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Foreign cemeteries in Japan

- Hashima Island (Gunkanjima)

References

- ↑ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- ↑ Boxer, The Christian Century In Japan 1549-1650, p. 100-101

- ↑ Diego Paccheco, Monumenta Nipponica, 1970

- ↑ so says the Jesuit account

- ↑ Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan, Richard Bowring and Haruko Laurie

- ↑ Screech, Timon. The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan: The Lens Within the Heart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. p15.

- 1 2 "Chapter II The Effects of the Atomic Bombings". United States Strategic Bombing Survey.

- ↑ How Effective is Strategic Bombing?: Lessons Learned From World War II to Kosovo (World of War). NYU Press. December 1, 2000. pp. 86–87.

- ↑ "Avalon Project - The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki".

- ↑ Bradley, F.J. (1999). No Strategic Targets Left. Turner Publishing Company. p. 103. ISBN 1-5631-1483-6.

- 1 2 Skylark, Tom (2002). Final Months of the Pacific War. Georgetown University Press. p. 178.

- ↑ Bruce Cameron Reed (October 16, 2013). The History and Science of the Manhattan Project. Springer Publishing. p. 400. ISBN 3-6424-0296-8.

- ↑ "BBC - WW2 People's War - Timeline".

- ↑ Robert Hull (October 11, 2011). Welcome To Planet Earth - 2050 - Population Zero. AuthorHouse. p. 215. ISBN 1-4634-2604-6.

- ↑ Nuke-Rebuke: Writers & Artists Against Nuclear Energy & Weapons (The Contemporary anthology series). The Spirit That Moves Us Press. May 1, 1984. pp. 22–29.

- ↑ Groves 1962, pp. 343–346.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al., pp. 396-397

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 396–397

- ↑ "AtomicBombMuseum.org - After the Bomb".

- ↑ "Nagasaki History Facts and Timeline".

- ↑ あすにかけ全国的に厳しい冷え込み続く 気象庁

- ↑ "平年値(年・月ごとの値)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- ↑ "観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- ↑ "長崎外国語大学 - Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies". Nagasaki-gaigo.ac.jp. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "お知らせ 長崎市平和・原爆のホームページが変わりました。". .city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ "長崎歴史文化博物館". Nmhc.jp. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- 1 2 "移転のお知らせ". .city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ The Encircled Serpent: A Study of Serpent Symbolism in All Countries and Ages - M. Oldfield Howey - Google Books. Books.google.com. 2005-03-31. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "長崎ランタンフェスティバル". Nagasaki-lantern.com. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Sister Cities of Nagasaki City". © 2008-2009 International Affairs Section Nagasaki City Hall. Archived from the original on July 29, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-10. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "International Relations of the City of Porto" (PDF). Municipal Directorateofthe Presidency Services International Relations Office. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nagasaki. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Nagasaki. |

- Nagasaki City official website (Japanese)

- Nagasaki City official website (English)

- Is Nagasaki still radioactive? - No. Includes explanation.

- Nagasaki after atomic bombing - interactive aerial map

- Nuclear Files.org Comprehensive information on the history, and political and social implications of the US atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Nagasaki Prefectural Tourism Federation

- Nagasaki Product Promotion Association

- Useful information for foreign residents, produced by Nagasaki International Association