Mondak, Montana

| Mondak | |

|---|---|

| Ghost town | |

|

Mondak, 1915 | |

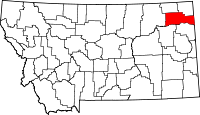

Mondak  Mondak Location of Mondak in Montana | |

| Coordinates: 48°01′13″N 104°02′50″W / 48.02028°N 104.04722°WCoordinates: 48°01′13″N 104°02′50″W / 48.02028°N 104.04722°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana |

| County | Roosevelt |

| Established | 1903 |

| Abandoned | 1925 |

| Named for | Proximity to Montana/Dakota border |

| Elevation | 2,070 ft (630 m) |

Mondak, Montana is a ghost town in Roosevelt County, which flourished c. 1903-1919, in large measure by selling alcohol to residents of North Dakota, then a dry state.[2]

Mondak—a name derived from the adjoining states—was created in 1903, mostly by local investors who realized that profit could be made by selling beer and liquor to North Dakotans. Because of its strategic location on the Missouri River and the Great Northern Railway, Mondak quickly became a thriving village. The first building was constructed in 1904, and Mondak soon boasted a bank, two hotels, three general stores, and several grain elevators. It also eventually had a church, a newspaper, a two-story brick school, and a part-time electric generating plant.[3] Locally raised grain and cattle were shipped to Minneapolis on the Great Northern, but the town’s most profitable business remained alcohol sales.

During its heyday, Mondak had at least seven saloons and a number of warehouses to store alcohol.[4] Gambling and prostitution were never legal but always winked at. There were many accidents involving inebriated men, and the crime rate was high for the size of the community. On April 4, 1913, a black construction worker killed Sheriff Thomas Courtney and a deputized citizen Richard Bermeister [5] and was promptly lynched by the residents.[6]

Mondak’s prosperity was short-lived. The area entered a drought cycle in 1916; and the Snowden Bridge, completed in 1913, reduced ferry traffic across the Missouri. In 1916 a fire destroyed several saloons and a warehouse and badly damaged a hotel and a general store.[7] In 1919 Montana instituted prohibition. Although Mondak was never entirely dry, prohibition “cramped Mondak’s style.” When the county seat, provisionally located in Mondak, moved to Poplar in 1920, Mondak’s decline accelerated. In early 1924, the railroad station closed,[8] and the bank, the town’s last viable business, closed in 1925. In 1928 another fire destroyed many remaining buildings.[9] The scant remains of the ghost town are on private property within a mile of Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site and within two miles of Fort Buford State Historic Site, North Dakota.[10]

Notes

- ↑ "Mondak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Sweetman, Alice M. (August 1965). "Mondak: Planned City of Hope Astride Montana-Dakota Border". Montana. 15: 12–27; Matzko, John (2001). Reconstructing Fort Union. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 26–32.

- ↑ Matzko (2001), p. 27. Although the church never had a resident minister, the town welcomed periodic visits from the noted Methodist prohibitionist Rev. William Van Orsdel. Sweetman & 1965 (p- 18) Lind, Robert W. (1992). Brother Van: Montana Pioneer Circuit Rider. Helena, MT: Falcon Press.

- ↑ Matzko (2001), p. 29.

- ↑ Helm, Merry (April 4, 2006). "Murder and Lynching at Mondak". Prairie Public Broadcasting.

- ↑ Matzko (2001), p. 29; Sweetman (1965), pp. 23–24. Booker T. Washington mentioned the lynching in a July 15, 1913 letter to the Boston Transcript. Harlan, Louis R.; Smock, Raymond W., eds. (1982). Booker T. Washington Papers. vol. 12. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 232.

- ↑ Yellowstone News. July 8, 1916. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Tough Town Closed Up". Grit, America's Greatest Family Newspaper. Williamsport, PA. February 24, 1924. p. 2, col. 4. "Passing of a Tough Town in Montana". The Deadwood Telegram. February 14, 1924. p. 1, col. 5.

- ↑ Matzko (2001), pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Thackeray, Lorna. "Booze Lubricated Mondak's Prosperity". Fairview Gazette.