Hurricane Donna

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Donna over the Florida Keys | |

| Formed | August 29, 1960 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 14, 1960 |

| (Extratropical after September 13) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 930 mbar (hPa); 27.46 inHg |

| Fatalities | 164-364 total |

| Damage | $900 million (1960 USD) |

| Areas affected | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Cuba, Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, eastern Canada |

| Part of the 1960 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Donna was a 1960 hurricane which brought severe damage to the Lesser Antilles, the Greater Antilles, and the East Coast of the United States, especially Florida, in August–September 1960. The fifth tropical cyclone, third hurricane, and first major hurricane of the season, Donna developed south of Cape Verde on August 29, spawned by a tropical wave to which 63 deaths from a plane crash in Senegal were attributed. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Donna by the following day. Donna moved west-northwestward at roughly 20 mph (32 km/h) and by September 1, it reached hurricane status. Significant deepening occurred during the next 30 hours, with Donna being a moderate Category 4 hurricane by late on September 2. Intensification continued and it reached its peak intensity early on September 4, with maximum sustained winds of 145 mph (230 km/h). Thereafter, it weakened slightly as it brushed the Lesser Antilles later that day. On Sint Maarten, the storm left a quarter of the island homeless and killed seven people. An additional five deaths were reported in Anguilla and there were seven other fatalities throughout the Virgin Islands. In Puerto Rico, severe flash flooding led to 107 fatalities, 85 of them in Humacao alone. Donna further weakened to a Category 3 hurricane late on September 5, but eventually became a Category 4 hurricane again. While passing through The Bahamas, several small island communities in the central regions of the country were leveled, but no damage total or fatalities were reported.

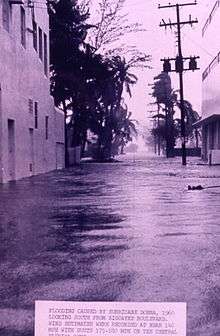

Early on September 10, Donna made landfall near Marathon, Florida with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h), hours before another landfall south of Naples at the same intensity. Florida bore the brunt of Hurricane Donna. In the Florida Keys, coastal flooding severely damaged 75% of buildings, destroyed several subdivisions in Marathon. On the mainland, 5,200 houses were impacted, which does not include the 75% of homes damaged at Fort Myers Beach; 50% of buildings were also destroyed in the city of Everglades. Crop losses were also extensive. A total of 50% of grapefruit crop was lost, 10% of the orange and tangerine crop was lost, and the avocado crop was almost destroyed. In the state of Florida alone, there were 13 deaths and $300 million in losses. Donna weakened over Florida and was a Category 2 hurricane when it re-emerged into the Atlantic from North Florida. By early on September 12, the storm made landfall near Topsail Beach, North Carolina as a strong Category 2 hurricane. Donna brought tornadoes and wind gusts up to 100 mph (155 km/h), damaging or destroying several buildings in Eastern North Carolina, while crops were impacted as far as 50 miles (80 km) inland. Additionally, storm surge caused significant beach erosion and structural damage at Wilmington and Nags Head. Eight people were killed and there were over 100 injuries. Later on September 12, Donna reemerged into the Atlantic Ocean and continued to move northeastward. The storm struck Long Island, New York late on September 12 and rapidly weakened inland. On the following day, Donna became extratropical over Maine.

Meteorological history

On August 29, a tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa near Dakar. That day, it is estimated a tropical depression developed along the wave southeast of Cape Verde. There was a lack of data for several days, but it is estimated that the system gradually intensified. On September 2, ships in the region suggested there was a tropical storm after reporting winds of over 50 mph (80 km/h). That day, the Hurricane Hunters flew into the system and observed a well-defined eye, along with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h).[1] Based on the data, the United States Weather Bureau office in San Juan, Puerto Rico initiated advisories on Hurricane Donna at 2200 UTC on September 2,[2] about 700 mi (1,100 km) east of the Lesser Antilles.[3] It is estimated that the storm attained hurricane status a day prior. The Azores High to the north was unusually powerful, which caused Donna to move to the west-northwest.[1] When advisories began, Donna was a major hurricane, which is the equivalent of a Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale; it would ultimately maintain this status for nine days.[4]

Continuing to the west-northwest, Donna strengthened further, and on September 4, Donna reached it's peak intensity, with maximum sustained winds of 145 mph (233 km/h).[5] After maintaining peak winds for about 12 hours, the hurricane weakened slightly as it approached the Lesser Antilles.[4] Late on September 4, the eye of Donna moved over Barbuda, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, and Anguilla, and passed just south of Anegada. Despite having weakened, Donna remained well-organized, described in the Monthly Weather Review as akin to "an intense, idealized hurricane." A weakening trough to the north turned the hurricane more northwesterly, bringing it within 85 mi (137 km) of the north coast of Puerto Rico. By September 7, Donna had turned more to the west after the ridge built to the north. Over the next few days, the intense hurricane moved slowly through the southern Bahamas without defined steering currents, and the eye passed near or over Mayaguana, Acklins, Fortune Island, and Ragged Island.[1]

While passing through the Straits of Florida, Donna brushed the northern coast of Cuba on September 9 with gale-force winds. Subsequently, a cold front moved eastward through the United States and weakened the ridge, causing the hurricane to turn more to the northwest. It re-intensified over warm sea surface temperatures,[1] and the hurricane's minimum barometric pressure dropped to 932 mbar (27.5 inHg) on September 10.[4] Between 0200 and 0300 UTC that day, the 21 mi (34 km) wide eye of Donna crossed through the Florida Keys just northeast of Marathon, with sustained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) and gusts to 178 mph (286 km/h). The hurricane continued to the northwest along the southwest coast of Florida, passing over Naples and Fort Myers before turning inland to the northeast. At 0800 UTC on September 11, Donna exited Daytona Beach into the western Atlantic with winds of about 105 mph (165 km/h), still as an organized hurricane. Accelerating to the northeast due to an approaching trough, the hurricane re-intensified slightly before making landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina, early on September 12. At 0900 UTC that day, Donna again emerged over open waters near Virginia, although it had weakened and the eye expanded to over 50 mi (80 km) in diameter. Late on September 12, the hurricane crossed Long Island and later moved through New England.[1] On September 13, Donna became extratropical over northern Maine before entering eastern Canada, having become associated with the approaching cold front. After moving across Quebec and Labrador, Donna reached the Labrador Sea and dissipated early on September 14.[1][4]

Preparations

At noon on September 3, a hurricane watch was issued for the Leeward Islands, which at 6 p.m was upgraded to a warning. Also at 6 p.m., hurricane watches were raised for Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, which at 6 a.m. on September 4, were upgraded to warnings. By 6 a.m. on September 5, hurricane warnings were dropped for the Leeward Islands, and at 9 a.m., southwest Puerto Rico and the Virgin Island's hurricane warnings were downgraded to gale warnings. By noon, all remaining hurricane warnings for Puerto Rico were changed to gale warnings.[6] In Puerto Rico, flood warnings were issued on September 5, although some residents in the region did not heed the notice; many returned to their homes after the hurricane passed to the north.[1] On Vieques Island, about 1,700 United States Marines evacuated to naval ships.[7] Officials advised small boats to remain at port, and thousands of residents evacuated to schools set up as Red Cross shelters.[8] Along the Cuban coast, about 3,000 people evacuated inland or to churches and schools,[9][10] while in the Bahamas, stores closed and boats were sent to port.[11]

Beginning on September 7, hurricane watches were put in place for the Florida coast from Key West to Melbourne. The next day, the watches were upgraded to hurricane warnings from Key West to Key Largo, with hurricane watches raised on the west coast northward to Fort Myers, and gale warnings issued from Key Largo to Vero Beach. By September 11, hurricane warnings were in effect for southern Florida from Daytona Beach on the east coast to Cedar Key on the west coast, including Lake Okeechobee. Gale warnings were in place northward from Cedar Key to St. Marks, as well as from Daytona Beach northward to Savannah, Georgia.[6] Evacuations in the Florida Keys disrupted traffic along the Overseas Highway.[9] The Air Force evacuated 90 Boeing B-47 Stratojets from Homestead Air Reserve Base. At Kennedy Space Center, the threat of the storm caused the launching of two missiles to be postponed.[11] Most flights out of Miami International Airport were canceled during the storm's approach. Officials closed schools in Miami and the Florida Keys,[10] and recommended residents in low-lying areas of the Florida Keys and southwestern Florida to evacuate. Ultimately, about 12,000 people in southern Florida sought refuge in storm shelters, two of which were damaged during the storm.[12] In Miami-Dade County alone, there were 77 storm shelters housing 10,000 people.[13]

At 5 p.m. on September 10, gale warnings were extended northward to Myrtle Beach. At 11 p.m., hurricane warnings were lowered in the Florida Keys but extended northward from Daytona Beach to Savannah, Georgia.[6] At 11 a.m. on September 11, all warnings were lowered south of Vero Beach and along the Florida west coast, while hurricane warnings were extended northward from Savannah to Myrtle Beach. At 5 p.m., hurricane warnings were lowered south of Fernandina Beach, while they were extended northward to include the entire North Carolina coast. Gale warnings were issued northward to Cape May. At 9 p.m., hurricane warnings were extended northward to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, while gale warnings and a hurricane watch were issued northward to Eastport, Maine.[14] Ships at dock in Newport, Rhode Island were towed out into the bay to weather the storm.[15] On September 12 at 5 a.m., hurricane warnings were extended northward to Eastport, and dropped south of Cape Hatteras. At 7 a.m., hurricane warnings were lowered south of Cape Charles. At 2 p.m., hurricane warnings were dropped south of Cape May. At 5 p.m., hurricane warnings were discontinued south of Manasquan, New Jersey. At 8 p.m., hurricane warnings expired south of Block Island. By 11 p.m. on September 12, all hurricane warnings had been lowered.[14]

Impact

Hurricane Donna was a very destructive hurricane that caused extensive damage from the Lesser Antilles to New England. At least 364 people were killed by the hurricane and property damage was estimated at $900 million (1960 USD).[16]

West Africa and Caribbean

The precursor to Hurricane Donna brought severe weather to the Dakar area of Senegal.[17] Air France Flight AF343, which was flying from Paris, France to Abidjan, Ivory Coast, attempted to land at the Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport as a layover. However, due to squally weather, the plane instead crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, killing all 63 people on board.[18] Heavy rainfall was also reported in Cape Verde on August 30.[1]

Hurricane Donna caused very extensive damage on Saint-Martin, killed 7 and left at least a quarter of the island's population homeless. A weather station in Sint Maarten reported sustained wind gusts of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a 952 mbar (28.1 inHg) pressure reading in the main airport.[1] Donna killed two people on Antigua.[19] During the passing of hurricane Donna, Anguilla recorded five deaths, including a woman who died when the roof of her house collapsed.

Despite passing only 35 mi (56 km) north of the island, Donna caused only minor damage on St. Thomas in the United States Virgin Islands. A station there reported a wind gust of 60 mph (97 km/h).[1] Some fences were toppled, while several houses were reported to have been damaged or destroyed. Electrical and telephone services were also disrupted. The highest daily rainfall total on the island was 8.78 inches (223 mm), causing minor local flooding. On Saint John, several small boats capsized.

While passing to the north of Puerto Rico, Donna produced winds of 38 mph (61 km/h) in San Juan. Along the north coast of the island, high tides of around 6 ft (1.8 m) and strong waves caused coastal flooding.[1] The hurricane dropped torrential rainfall, peaking at 16.23 in (412 mm) at Naguabo in the central portion of the island. Large areas of eastern Puerto Rico received over 10 in (250 mm) of precipitation.[20] The hurricane left about 2,500 people homeless on the island.[11] Despite advanced warning of the floods, the hurricane killed 107 people on the island, of which 84 were in Humacao.[1]

In Haiti, the southern periphery of the hurricane killed three people in Port au Prince.[19] Later, Donna brushed the north coast of Cuba with strong winds and heavy rainfall,[1] causing damage along much of the coast.[9] In Gibara, the storm wrecked 80 houses.[10]

Turks and Caicos and Bahamas

On Grand Turk in what is now the Turks and Caicos, Donna produced winds of 58 mph (93 km/h), as the strongest winds remained north of the island. However, the storm dropped heavy rainfall of over 20 in (510 mm), much of which fell in a 12‑hour period.[1] Despite the rains, damage there was minor.[11]

In the Bahamas, the anemometer at Ragged Island blew away after registering a 150 mph (240 km/h) wind gust. At Mayaguana, where residents evacuated to a missile tracking base, hurricane-force winds raged for 13 hours.[1] The winds largely destroyed the village of Abraham's Bay on the island.[21] Andros experienced hurricane-force winds for a few hours, and winds on Fortune Island were estimated at 173 mph (278 km/h) before the anemometer blew away. The strongest winds remained south of the northwestern Bahamas, which limited damage there.[1] Donna cut communications between several islands.[11]

Several small island communities in the central Bahamas were leveled. North Caicos reported 20 inches (510 mm) of rainfall in 24 hours.[22]

United States

Fifty people were reported dead in the United States, with damages totaling to $3.35 billion.[23] Donna crossed directly over Texas Tower 4, causing severe damage to the structure and leading to its eventual loss in January 1961.[24]

Donna was the only hurricane to affect every state along the East Coast with hurricane-force winds.[25]

Florida

The U.S. state of Florida received the most damage from Hurricane Donna. Portions of southern and western Florida received over 10 in (250 mm) of rainfall from the hurricane, peaking at 13.24 in (336 mm).[20] Strong winds were observed in the state, with a sustained wind speed of 120 mph (190 km/h) in Tavernier and a gusts up to 150 mph (240 km/h) at Sombrero Key Light.[26] In Miami, winds reached 97 mph (156 km/h). Southeast of the city, high waves washed a 104 ft (32 m) freighter onshore an island.[12] The highest observed storm surge of 13 ft (4.0 m) was reported at Marathon. The hurricane also lashed Southwest Florida, where tides were 4 to 7 feet (1.2 to 2.1 m) above normal.[26]

In Miami-Dade County, thousands of low-lying homes in the Homestead area were flooded. Overall, 857 houses in the country were destroyed, while about 2,317 others suffered damage. Significant agricultural losses were also reported. Donna was the first hurricane to affect Miami, Florida since Hurricane King in October 1950.[27]

In the Florida Keys, some areas experienced "almost complete destruction".[26] Further north between Marathon and Tavernier, an estimated 75% of buildings were extensively damaged. In the former, tides inundated the city and destroyed several subdivisions.[26] In Key West, one death was confirmed and 71 people were injured. About 564 homes were demolished and an additional 1,382 were damaged, 583 of them severely.[28] Storm surge inundated parts of the Overseas Highway and washed out several portions near bridges. Many boats and docks were severely damaged or destroyed. Additionally, the pipeline supplying water to the Florida Keys was wrecked in three places.[26]

Large tracts of mangrove forest were lost in the western portion of Everglades National Park, while at least 35% of the white heron population in the park were killed.[29] In Everglades, about 50% of buildings were destroyed due to strong winds and coastal flooding. Late on September 11, 2 to 3 feet (0.61 to 0.91 m) of water was reported throughout the area. The city briefly became inaccessible due to inundated roads. Many small building were destroyed, and roofs were blown off or damaged. Thousands of trees were toppled,[26] blocking portions of the Tamiami Trail.[12] Throughout Collier County, strong winds and coastal flooding combined destroyed 153 homes, inflicted major impact on an additional 409, and 1,049 others suffered minor damage.[30] The turn into southern Florida lessened damage in the Tampa area.[31]

Throughout the state, the storm destroyed 2,156 homes and trailers, severely damaged 3,903, and inflicted minor impact on 30,524 others. Approximately 391 farm buildings were destroyed, an additional 989 suffered extensive impact, and 2,499 others received minor damage. Roughly 174 buildings were demolished, 1,029 received major impact, and 4,254 suffered minor damage. Additionally, 281 boats were destroyed or severely damaged. A total of 50% of grapefruit crop was lost, 10% of the orange and tangerine crops were ruined, and the avocado crop was almost destroyed. With at least $350 million in damage in Florida alone, Donna was the costliest hurricane to impact the state, at the time. Additionally, there were 13 confirmed fatalities, six from drowning, four from heart attacks, two from automobile accidents, and two from electrocution. About 1,188 others were injured.[32]

Southeastern United States and Mid-Atlantic

The storm brought minor impact to Georgia. Wind gusts of 50 mph (80 km/h) along the coast felled trees and tree limbs, resulting in electrical and telephone service outages. In Brunswick, a power outage at the power plant caused a minor explosion. Heavy rainfall temporarily flooded some streets in the city. Further north in South Carolina, gale-force winds were reported along the coast, but caused little damage. A tornado spawned in the Charleston area destroyed several houses and severely damaged a number of others, and injured a few people by flying glass. Damage from this tornado was over $500,000. Another tornado touched down in Garden City and destroyed and extensively damaged six buildings.[26] In Beaufort County, many trees were uprooted, power lines were downed, homes were unroofed, piers were destroyed, and there was significant damage to corn and soybean crops.[33]

In North Carolina, Donna brought two tornadoes to the state. The first of which damaged several small buildings in Bladen County. The second tornado was spawned in Sampson County, where it destroyed a dwelling with eight occupants, all of whom were hospitalized. Along the coast, wind gusts as high as 100 mph (155 km/h) damaged or destroyed several buildings. Additionally crops were impacted as far as 50 miles (80 km) inland. Storm tides ranging from 4 to 8 feet (1.2 to 2.4 m) above normal caused significant beach erosion and structural damage Wilmington and Nags Head.[26] Additionally, Topsail Beach was reported to have been 50% destroyed. In Southport, the town docks were almost completely demolished.[34] There were eight deaths, including three from drowning, two from falling trees, two from weather-related traffic accidents, and one from electrocution. At least 100 people were injured enough to require hospitalization.[26] Damage in North Carolina exceeded $5 million, with the worst impact occurring in New Hanover County.[34]

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Cost (2015 USD)[37] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Miami" | 1926 | $190.3 billion |

| 2 | Katrina | 2005 | $130.9 billion |

| 3 | "Galveston" | 1900 | $120.4 billion |

| 4 | "Galveston" | 1915 | $82.3 billion |

| 5 | Andrew | 1992 | $67.5 billion |

| 6 | "New England" | 1938 | $47.5 billion |

| 7 | "Cuba–Florida" | 1944 | $46.9 billion |

| 8 | "Okeechobee" | 1928 | $40.6 billion |

| 9 | Ike | 2008 | $34.1 billion |

| 10 | Donna | 1960 | $32.4 billion |

| Main article: List of costliest Atlantic hurricanes | |||

In Virginia, the east coast of the state reported hurricane-force winds, while gusts reached up to 89 mph (143 km/h) in Virginia Beach.[17] Strong winds toppled trees and electrical wires, which blocked streets. Additionally, buildings suffered roof damage and broken windows; some structures were completely destroyed. Offshore, rough seas sunk or destroyed numerous small crafts, while a 12,000 tonnes (26,000,000 lb) vessel was driven aground. The storm killed three people in Virginia; two of the deaths occurred when barge collided when a freighter and later sank, and another after a man attempted to safeguard his boat. Strong winds and heavy rains were observed in eastern Maryland. Ocean City suffered the worst impact, with over $300,000 in property damage. The storm also impacted crops in the area, especially corn and apples. Effects from the storm in Delaware were similar, with property damage and considerable losses to corn and apple crops. In Pennsylvania, wind gusts up to 59 mph (95 km/h) in the southeastern portions of the state toppled many trees and utility wires. Heavy rains and poor drainage in some areas flooded basements, lawns, and streets. Low-lying areas in Bucks and Montgomery counties were inundated with up to 3 feet (0.91 m) of water after many streams and creeks nearby overflowed. One death in the state was reported after a boy was swept into a swollen creek behind his home in Sharon Hill.[26]

Winds as strong as 100 mph (160 km/h) were observed along the coast of New Jersey. Rainfall in the state was generally between 5 and 6 inches (130 and 150 mm),[26] with a peak of 8.99 inches (228 mm) near Hammonton.[38] Damage from the storm was most severe in Atlantic, Cape May, Monmouth, and Ocean counties, where numerous boats, docks, boardwalks, and cottages were damaged or destroyed.[26] A resort area in Cliffwood Beach, New Jersey saw its boardwalk and tourist attractions destroyed by the hurricane, and the area has never recovered. Losses to agriculture were significant, with damage to apple and peach trees "considerable", the former of which lost about one-third of its crops. Wind damage to corn, Sudan grass, and sorgham resulted in a delay in their harvest. Nine deaths were reported in the state of New Jersey. In southeastern New York, heavy rains, hurricane-force winds, and "unprecedented" high tides were observed. Severe small stream flooding caused significant damage, especially on Long Island, the waterfront of New York City, and further north in Greene County. The storm caused three fatalities in the state, two from drowning and another from a person crushed by a falling tree.[26]

Elsewhere in North America

In Connecticut, strong winds left 15,000 people without telephone service, while 88,000 homes lost electricity. Along the coast, tides caused beach erosion, inundated streets, and weakened foundations. Four seaside cottages were destroyed. Crop damage was isolated and mainly limited to apples and corn. In Rhode Island, the storm brought a wind gust as strong as 130 mph (210 km/h) to Block Island. Telephone and electrical services were severely disrupted. Along the coast, high tides significantly impacted or destroyed about 200 homes at Narragansett Bay and Warwick cove. Damage to these vessels collectively totaled to over $2 million. Agriculture also suffered impact, particularly to fruit, timber, and poultry, especially in Newport and Portsmouth.[26]

Strong winds were also observed in Massachusetts, with a wind gust of 145 mph (233 km/h) at the Blue Hill Observatory.[1] Extensive losses to apple orchards occurred, as the fruit was blown out of trees. Widespread telephone and power outages were reported.[26] The strong southwest winds associated with Donna, in combination with very little rainfall, led to a significant deposit of salt spray, which whitewashed southwest-facing windows. Many trees and shrubs saw their leaves brown due to the salt.[39] However, in other areas, 4 to 6 in (100 to 150 mm) of precipitation fell, causing some washouts and local flooding. Waves along the coast ripped of small boats and pleasure craft from their moorings and subsequently smashed them against rocks or seawalls.[26]

In Vermont, winds damaged trees, tree branches, and power lines, causing telephone and electrical service outages in a few communities. Rainfall totals ranged from 2 to 5 in (51 to 127 mm), resulted in washouts in some areas. Damage to apple orchards totaled $50,000. Along the coast of New Hampshire, many boats were smashed or damage in some way. Strong winds felled trees and power lines, causing residents in the southern portions of the state to lose telephone service and electricity. Additionally, apple orchard suffered $200,000 in damage. Rainfall in the state peaked at 7.25 in (184 mm) near Peterborough, resulting in local flooding and washouts.[26]

Along the coast, large waves damaged 15 to 20 boats in Falmouth harbor. Total boat damage was estimated at $250,000. Coastal residents in low-lying beach areas of Cumberland and York counties were evacuated. Several counties lost power during the storm. In Southwest Harbor, lightning struck the Dirigo Hotel, causing a fire that resulted in $100,000 in damages. Winds caused a lost of telephone and electrical services in Auburn-Lewiston area due to falling trees and tree branches. Television antennas were damaged, as were several signs including a Sears sign. In addition, 25% to 40% of the apple crop was destroyed.[40]

After becoming extratropical, the remnants of Donna continued northeastward into New Brunswick, Quebec, and then Labrador. Wind gusts of 53 mph (85 km/h) in Quebec snapped electrical poles and trees. One death occurred when a man suffered a heart attack when his home was threatened by a fire. Additionally, weather-related traffic accidents in the province resulted in two injuries.[41]

Depictions in popular culture

Nobel Prize-winner John Steinbeck wrote about Hurricane Donna in his 1962 non-fiction memoir Travels with Charley: In Search of America. Steinbeck had had a truck fitted with a custom camper-shell for a journey he intended to take across the United States, accompanied by his poodle Charley. He planned on leaving after Labor Day from his home in Sag Harbor, Long Island, New York. Steinbeck delayed his trip slightly due to Donna, which made a direct hit on Long Island. Steinbeck wrote of saving his boat during the middle of the hurricane, during which he jumped into the water and was blown to shore clinging to a fallen branch driven by the high winds. It was an exploit which foreshadowed his fearless, or even reckless, state of mind to dive into the unknown.[42]

The winds of Donna can be seen in the feature film Blast of Silence (1961); a fist fight scene on Long Island had been previously scheduled, and the filmmakers decided to go ahead and shoot the exterior scene despite the hurricane.[43]

Aftermath, records and retirement

Following the storm, President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower issued a disaster declaration for Florida and North Carolina, allowing residents of those states to be eligible for public assistance.[44][45]

The United States military sent a plane carrying doctors and food from Patrick Air Force Base to Mayaguana in the Bahamas.[21] Crews of doctors and workers with food and supplies left from Key West and Miami to traverse the Florida Keys, bringing aid to impacted residents.[12] In Marathon, a large reconstruction program rehabilitated the key by Christmas.[46]

Coral reefs were damaged in the Key Largo National Marine Sanctuary by the hurricane.[47] Donna caused a significant negative impact on aquatic life in north Florida Bay. Marine life was either stranded by retreating salt water which had been driven inland or killed by muddied waters in its wake. Oxygen depletion due to animals perishing in the hurricane caused additional mortality. Although salinity levels returned to normal within six weeks, dissolved oxygen concentrations remained quite low for a longer time frame. Marine life was scarce for several months in areas of greatest oxygen depletion. Sports fishing in the area took a few months to recover. Juvenile pink shrimp moved from their estuarine nursery grounds into deeper water about 60 mi (97 km) offshore, where they were subsequently captured by fishermen.[48] A Caspian tern was swept up the North American coast well to the north of its traditional breeding grounds, to Nova Scotia, which was witnessed four hours after the storm went by Digby Neck.[49]

Because of its devastating impacts and the high mortality associated with the hurricane, the name Donna was retired, and will never again be used for an Atlantic hurricane; the name was replaced by Dora in 1964.[50]

See also

- Hurricane Charley – similar track across I-4 corridor

- Hurricane Luis – similarly strong hurricane in 1995 that struck the northeastern Caribbean Sea, but subsequently turned out to sea

- List of Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Delaware hurricanes

- List of Florida hurricanes (1950–74)

- List of New England hurricanes

- List of New York hurricanes

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (1950–79)

- List of wettest tropical cyclones in Massachusetts

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Gordon E. Dunn (March 1961). "The Hurricane Season of 1960" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. United States Weather Bureau. 89: 99, 104–107. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1961)089<0099:thso>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ↑ Ralph Higgs (1960-09-02). Hurricane Advisory Number 1 Donna (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ↑ Tropical Storm "Donna" September 2-13, 1960 Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- 1 2 3 4 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ Ralph Higgs (1960-09-04). Hurricane Advisory Number 8 Donna (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- 1 2 3 Hurricane "Donna" Chronology, September 2-13, 1960 (Report). United States Weather Bureau Office of Climatology. 1960. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ↑ "Puerto Rico Braces for Hurricane". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. 1960-09-05. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- ↑ "Hurricane Howls Towards Mainland". The Gadsden Times. Associated Press. 1960-09-05. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- 1 2 3 "Deadly 'Donna' Seems Sure to Slam into Florida". The Times-News. United Press International. 1960-09-09. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- 1 2 3 "Storm Nears Florida Coast". The Windsor Star. 1960-09-09. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Savage Hurricane 'Donna' Aims for Florida; Winds 150 MPH". The Times-News. United Press International. 1960-09-08. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- 1 2 3 4 "Gulf Beaches Evacuated; Donna Slashes Pinellas". The Evening Independent. Associated Press. 1960-09-11. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ "Donna Late, But Miami Hurt". The Evening Independent. Associated Press. 1960-09-11. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- 1 2 Hurricane "Donna" Chronology page 2, September 2-13, 1960. United States Weather Bureau Office of Climatology (1960). Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Ron Fritz (2008). USS Fred T. Berry DD/DDE 858 Ship's History Addenda: Hurricane Donna. Ron Fritz. Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Edward N. Rappaport and Jose Fernandez-Partagas. The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved on 2008-10-13.

- 1 2 David M. Roth (July 16, 2001). Late Twentieth Century. Weather Prediction Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ↑ Accident description (Report). Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Donna Threatens Florida". Kentucky New Era. Associated Press. 1960-09-06. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- 1 2 David M. Roth (2013-03-06). Hurricane Donna - September 3-12, 1960 (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Donna Turns Slightly Toward North". Associated Press newspaper The News and Courier. 1960-09-09. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- ↑ 2007 Hurricane Guide: Are You Prepared? Turks & Caicos Islands Red Cross (2007). Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake; Edward N. Rappaport; Christopher W. Landsea (2007-04-15). "The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2006 (And Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts)" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ Thomas Ray. "A history of Texas Towers in air defense 1952-1964". The Texas Tower Association. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ "Hurricane History". National Hurricane Center. 2008. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena: September 1960 (PDF). National Climatic Data Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2014. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (1960). Climatological Data: Florida - September 1960, pp. 2. Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Special Storm and Flood Report by the American Red Cross for U.S. Weather Bureau. American Red Cross (Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1960-10-20. p. 2. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ↑ Jason P. Dunion; Christopher W. Landsea; Samuel H. Houston; Mark D. Powell (2003). A Reanalysis of the Surface Winds for Hurricane Donna of 1960 (PDF) (Report). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ↑ Special Storm and Flood Report by the American Red Cross for U.S. Weather Bureau. American Red Cross (Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1960-10-20. p. 1. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ↑ Dick Bothwell (1960-09-11). "Back to Normal By Friday". St. Petersburg Times. United Press International. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ "Here's What Donna Did". National Hurricane Center. 1960. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Losses Heavy As Donna Rips Through County" (PDF). Beaufort County Community College. 1960. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- 1 2 Scott Nunn (2010-09-15). "Back Then - Hurricane Donna rushes ashore in 1960". Star-News. p. 2. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ↑ Pielke, Roger A., Jr.; Gratz, Joel; Landsea, Christopher W.; Collins, Douglas; Saunders, Mark A.; Musulin, Rade (2008). "Normalized Hurricane Damage in the United States: 1900–2005" (PDF). Natural Hazards Review. 9 (1): 29–42. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2008)9:1(29). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ↑ Blake, Eric S.; Landsea, Christopher W.; Gibney, Ethan J. (2011). "The Deadliest, Costliest, and the most intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts)" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6.

- ↑ United States nominal Gross Domestic Product per capita figures follow the Measuring Worth series supplied in Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2016). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved April 10, 2016. These figures follow the figures as of 2015.

- ↑ Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ Arnold Arboretum (1961-09-08). "Hurricane "Donna" and its After Effects to a Chatham, Massachusetts, Garden" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved 2014-06-25.

- ↑ Wayne Cotterly (2002-10-21). Hurricane Donna-(1960) (Report). Retrieved 2014-06-25.

- ↑ 1960-Donna (Report). Environment Canada. 2009-11-05. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ↑ John Steinbeck (1962). Travels with Charley: In Search of America. Penguin Books. ISBN 1101615168. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ↑ "Trivia for Blast of Silence (1961)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Donna (DR-106). Federal Emergency Management Agency (Report). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ↑ North Carolina Hurricane Donna (DR-107). Federal Emergency Management Agency (Report). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ↑ Larry Solloway (1960-12-25). "Face-Lifting Erases Scar Donna Left in Keys". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ "The Effects of African Dust on Coral Reefs and Human Health". United States Geological Survey. 2010-06-14. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ Tabb, Durbin C.; Jones, Albert C. (1962). "Effect of Hurricane Donna on the Aquatic Fauna of North Florida Bay". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 91 (4): 375–378. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1962)91[375:eohdot]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ "Caspian Tern". Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History. 1998-02-20. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954 (Report). National Hurricane Center. 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Donna. |

- Images from the Naples Daily News of Donna

- Historic Images of Florida Hurricanes (Florida State Archives)

- NOAA Hurricane Research Division Donna page

- HPC Rainfall Page on Donna