Hurricane Alicia

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

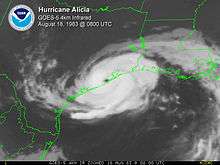

Hurricane Alicia before landfall. | |

| Formed | August 15, 1983 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 20, 1983 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 963 mbar (hPa); 28.44 inHg |

| Fatalities | 21 direct |

| Damage | $2.6 billion (1983 USD) |

| Areas affected | Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska |

| Part of the 1983 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Alicia was the costliest tropical cyclone in the Atlantic since Hurricane Agnes in 1972. Alicia was the third depression, the first tropical storm, and the only major hurricane of the 1983 Atlantic hurricane season. It struck Galveston and Houston, Texas directly, causing $2.6 billion (1983 USD; US$6.19 billion 2016) in damage and killing 21 people; this made it the worst Texas hurricane since Hurricane Carla in 1961.[1] In addition, Alicia was the first billion-dollar tropical cyclone in Texas history.[2]

Hurricane Alicia was the first hurricane to hit the United States mainland since Hurricane Allen in August 1980. The time between the two storms totaled three years and eight days (1,103 days).[3] Hurricane Alicia became the last major hurricane (Category 3 or higher) to strike Texas until the stronger Hurricane Bret in 1999 made landfall. Alicia was the first storm for which the National Hurricane Center issued landfall probabilities.[4]

Hurricane Alicia was notable for the delayed post storm evacuation of Galveston Island (since the eye of the storm traveled the evacuation route up Interstate 45 from Galveston to Houston). The hurricane was also notable for the shattering of many windows in downtown Houston by loose gravel from the roofs of new skyscrapers and by other debris, prompting changes to rooftop construction codes.

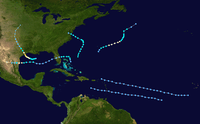

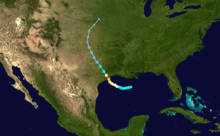

Meteorological history

The origins of Hurricane Alicia were from a cold front that extended from New England through the central Gulf of Mexico. On August 14, mesoscale low-pressure area developed off the Alabama and Mississippi coastlines.[1] Around 0100 UTC on August 15, the low had maintained convection, or area of thunderstorms, for 12 hours, as well as a circulation for six hours; as a result, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began issuing Dvorak classifications on the system.[5] By a few hours later, the deep convection became organized in the circulation's southern semicircle, which prompted a Hurricane Hunters flight into the system.[6] At 1200 UTC that day, the system developed into Tropical Depression Three about 350 miles (560 km) south-southwest of the Mississippi River Delta.[7] A few hours later, the Hurricane Hunters confirmed its development.[8] Such development along the tail end of a cold front is more typical earlier or later in the hurricane season.[9]

After becoming a tropical cyclone, the depression was moving slowly westward, due to a ridge to its north.[1] A Hurricane Hunters flight late on August 15 reported that the depression reached winds of 50 mph (80 km/h); as a result, the NHC upgraded the cyclone to Tropical Storm Alicia. At the time of its upgrade, the storm was located in an area of higher than normal atmospheric pressure, although conditions favored further development.[10] Due to high pressures surrounding the storm, Alicia was a smaller than normal tropical cyclone; as a result, it produced stronger than normal winds, in comparison to its minimum central pressure.[1] The storm continued slowly to the west-northwest, and by August 17 attained hurricane status, about 160 miles (255 km) southeast of Galveston, Texas.[7] Shortly thereafter, an eye became visible on radar,[11] as the hurricane executed several small loops.[9] Its slow movement over warm waters, in addition to an anticyclone becoming established over the hurricane, caused Alicia to undergo rapid deepening.[1]

At 0600 UTC on August 18, the winds reached 115 mph (185 km/h), just before Alicia made landfall about 25 mi (40 km) southwest of Galveston, Texas.[7] Upon moving ashore, the gale-force winds extended 125 mi (201 km) from the center,[12] and hurricane-force winds spread across an area from Freeport to 60 mi (97 km) northeast.[13] Its atmospheric pressure was 962 mbar (hPa; 28.41 inHg) around the time of landfall,[7] and radar imagery indicated the presence of a rare double-eye structure.[9] Alicia quickly weakened, passing over central Houston with sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). It accelerated toward the northwest, weakening to tropical storm status late on August 18 and to tropical depression status twelve hours later.[7] Tropical Depression Alicia moved into Oklahoma and interacted with an approaching frontal trough. By 0600 UTC on August 20, Alicia had transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over northwestern Oklahoma, and by the next day it was no longer identifiable after merging with the trough over eastern Nebraska.[1][7]

Preparations

Several watches and warnings were issued in association with Alicia. The first ones were a gale warning and a hurricane watch for the area between Corpus Christi, Texas and Grand Isle, Louisiana issued on August 16. On August 17, a hurricane warning was issued for the coastline from Corpus Christi to Morgan City, Louisiana, and later for Port Arthur, Texas southward.[4] Initially, however, residents did not take the warnings seriously. Galveston Mayor E. Gus Manuel, against the advice of Texas Governor Mark White, ordered the evacuation of only low-lying areas.[14] As a result, only 10 percent of the population living behind the seawall chose to leave when Alicia came ashore. In contrast, about 30 percent of Galveston's population evacuated the island when Hurricane Allen threatened the eastern Texas coastline in 1980.[15] Throughout the day, however, as the increasing winds began to cause damage in Galveston, people grew more concerned. The mayor finally ordered a widespread evacuation of the island after midnight on August 18, but by then, the bridges to the mainland were uncrossable.[14]

Impact

Texas

Galveston reported 7 3⁄4 in (197 mm) of rain, Liberty reported 9 1⁄2 in (241 mm) of rain, and Greens Bayou reported almost 10 in (250 mm). Centerville reported over 8 inches (200 mm), with Normangee and Mexia reporting over 7 in (180 mm).[16] Maximum rainfall in the Houston area in Harris County was about 10–11 in (250–280 mm), while 8 in (200 mm) of rain was reported in Leon County and 9 in (230 mm) in the Sabine River area. High gusts were reported throughout Texas, with a maximum gust of 125 mph (201 km/h) reported on the Coast Guard cutter Buttonwood (WLB-306) stationed at the northeastern tip of Galveston Island.[9] Pleasure Pier reported tides of 8.67 ft (2.64 m), with Pier 21 reporting a little over 5.5 ft (1.7 m). Baytown, Texas reported 10–12 ft (3.0–3.7 m) tides, and Morgan City reported 12.1 ft (3.7 m), the highest recorded as a result of Alicia.[16] The storm also caused extensive disruption of power services. A Paul Simon-Art Garfunkel reunion concert scheduled for the Houston Astrodome was canceled due to the coming storm.

Twenty-three tornadoes were reported in association with Alicia. Fourteen of those were located in the Galveston and Hobby Airport area. The other nine were concentrated around Tyler to Houston, Texas,[13] ranging around F2 on the Fujita scale.[15]

A major oil spill occurred around Texas City, and an ocean-going tugboat capsized 50 miles (80 km) off the Sabine Pass coast.[17] The Coast Guard Air Station Houston (AIRSTA) weathered Alicia with little damage, and afterwards AIRSTA's helicopters assisted residents with evacuation, supply, and survey flights.

Sixty gallons of water had to be removed from the National Weather Service (NWS) office in Galveston;[17] this weather office also temporarily lost its radar.[18] Houston suffered billions of dollars in damage. Thousands of glass panes in downtown skyscrapers were shattered by gravel blown off rooftops.[15] Although Alicia was a small Category 3 hurricane, a total of 2,297 dwellings were destroyed by Alicia, with another 3,000+ experiencing major damage. Over ten thousand dwellings had minor damage.[13]

In Galveston, the western beach had its public beach boundary shifted back about 150 ft (46 m).[19] About 5 feet (1.5 m) of sand was scoured, leaving beachfront homes in a natural vegetation state. This moved many beachfront homes onto public beach, and the Attorney General's office declared that they were in violation of the Texas Open Beaches Act and forbade the repair or rebuilding of those homes.[19] The Corps of Engineers stated that if the Galveston Sea Wall had not been there, that another $100 million (1983 USD; $238 million 2016 USD) in damage could have occurred.[19] Also, if Alicia had been the size of Hurricane Carla from 1961, damage could have easily doubled or possibly tripled.[19] Alicia damaged chemical and petrochemical plants in Houston.[20]

Elsewhere

As Alicia progressed northward, it produced heavy precipitation in several other areas. In Oklahoma, the rain amounted to 5.51 in (140 mm) in south-central portions of the state. Parts of Kansas and Nebraska received 1 to 3 in (25 to 76 mm) of rainfall. Other states, including Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota, Louisiana and Wisconsin experienced light rainfall from the remnants of the storm.[21]

Aftermath

The Red Cross provided food and shelter to 63,000 people in the hurricane's wake, costing about $166 million (1983 USD; $395 million 2016 USD).[13][19] FEMA gave out $32 million (1983 USD; $76.2 million 2016 USD) to Alicia's victims and local governments; $23 million (1983 USD; $54.7 million 2016 USD) of that was for picking up debris spread after the storm.[22] More than 16,000 people sought help from FEMA's disaster service centers. The Small Business Administration, aided with 56 volunteers, interviewed over 16,000 victims, and it was predicted that about 7,000 loan applications would be submitted. The Federal Insurance Agency had closed over 1,318 flood insurance cases from Alicia's aftermath, however only 782 received final payment.[22]

On September 23 and September 24, 1983, in the wake of Alicia, two subcommittees of the U.S. House of Representatives held hearings in Houston. The hearing on September 23 were to examine the primary issues of the NWS during Alicia, the effectiveness of the NWS in current procedures, and the use of the NWS. The second hearing, which occurred on September 24, was to discuss the damage and recovery efforts during Alicia.[22] During the September 23 hearing, witnesses agreed that the NWS did well before and during the emergency caused by Alicia. NWS forecasters also testified in which they said they gratified themselves that their predictions were well "on target" and that the local emergency plans had worked so well, which saved many lives. Mayor Gus Manuel on Galveston claimed that the NWS did an excellent job during Alicia. He was also very impressed about their landfall predictions on August 17.[22] During the September 24 hearing, evidence was presented which demonstrated the need for improving readiness to cope with disasters, such as Alicia. Mayor Manuel mentioned that his town needed stronger building codes, which were under review.[22]

Retirement

Due to the severe damage, the name "Alicia" was retired in the spring of 1984 by the World Meteorological Organization, and will never be used again for an Atlantic hurricane. It was the first name to be retired since Hurricane Allen in 1980.[23] It was replaced with "Allison" for the 1989 season.[24] Coincidentally, in 2001 the name "Allison" was retired after striking the same area as Alicia.[23][25]

In popular culture

The approach and eventual landfall of Alicia is a central plot point in a Season 1 episode of the AMC television drama Halt and Catch Fire.[26]

See also

- List of Texas hurricanes

- List of retired Atlantic hurricane names

- Timeline of the 1983 Atlantic hurricane season

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Hurricane Alicia Preliminary Report" (GIF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 1983. p. 1. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Texas Governors". Austin, Texas: Texas State Library and Archives Commission. 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ↑ "Chronological List of All Hurricanes Which Affected The Continental United States 1851 - 2007". Hurricane Research Division. Silver Spring, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Alicia Preliminary Report". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 1983. p. 4. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Miami SFSS/NHC Tropical and Subtropical Cyclone Classification". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. August 15, 1983. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Reconnaissance Aircraft Summary of the Day". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. August 15, 1983. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ Gerrish, Harold P. (August 15, 1983). "Preliminary Depression Statement". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Storm Development and History". Washington D.C.: United States Army. 2007. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ↑ Gerrish, Harold P. (August 15, 1983). "Tropical Storm Alicia Discussion". Miami, Florida. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ↑ Gerrish, Harold P. (August 17, 1983). "Tropical Cyclone Discussion Hurricane Alicia". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ↑ Lawrence, Miles B. (August 18, 1983). "Hurricane Alicia Intermediate Advisory". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Hurricane Alicia Preliminary Report" (GIF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 1983. p. 2. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- 1 2 Isaacson, Walter (August 29, 1983). "Coping with Nature newspaper". Time Magazine. Time Warner. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Hurricane Alicia, 1983". U.S.A. Today. Gannett. August 30, 1999. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Alicia Preliminary Report" (GIF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 1983. p. 5. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- 1 2 National Weather Office (2007). "Texas Hurricane History: Late 20th Century". Lake Charles, Louisiana: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 13, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ↑ "Warnings". Washington D.C.: United States Army. 2007. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 National Weather Office — Houston-Galveston (2007). "Upper Texas Coast Tropical Cyclones in the 1980s". Dickinson, Texas: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 28, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ↑ Levitan, Mark (2007). "Are Chemical Plants Really Safe?" (PDF). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ↑ Roth, David M. (May 1, 2007). "Hurricane Alicia - August 14-22, 1983". Silver Spring, Maryland: Hydrometeorogical Prediction Center. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Hurricane Alicia: Prediction, Damage & Recovery Efforts" (PDF). Subcommittee on Natural Resources, Agriculture Research and Environment. 1983. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 5, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- 1 2 "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. March 16, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ↑ Associated Press (June 1, 1989). "4 hurricane predicted for Atlantic in 1989". Bal Harbour, Florida: Star-News. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (February 8, 2002). "Tropical Storm Allison Tropical Cyclone Report". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ↑ Perkins, Dennis (July 7, 2014). "Halt and Catch Fire: "Landfall"". Chicago: A.V. Club. Retrieved July 7, 2014.