Host–guest chemistry

In supramolecular chemistry, host–guest chemistry describes complexes that are composed of two or more molecules or ions that are held together in unique structural relationships by forces other than those of full covalent bonds. Host–guest chemistry encompasses the idea of molecular recognition and interactions through noncovalent bonding. Noncovalent bonding is critical in maintaining the 3D structure of large molecules, such as proteins and is involved in many biological processes in which large molecules bind specifically but transiently to one another. There are four commonly mentioned types of non-covalent interactions: hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic interactions.[1]

Common host molecules

Common host molecules are cyclodextrins, calixarenes, pillararenes, cucurbiturils, porphyrins, metallacrowns, crown ethers, zeolites, cyclotriveratrylenes, cryptophanes, carcerands, and foldamers.

Host–guest chemistry is observed in inclusion compounds, Intercalation compounds, clathrates, and molecular tweezers.

Thermodynamic principles of host–guest interactions

There is an equilibrium between the unbound state, in which host and guest are separate from each other, and the bound state, in which there is a structurally defined host–guest complex:

- H ="host" , G ="guest" , HG ="host–guest complex"

The "host" component can be considered the larger molecule, and it encompasses the smaller, "guest", molecule. In biological systems, the analogous terms of host and guest are commonly referred to as enzyme and substrate respectively.[2]

The thermodynamic benefits of host–guest chemistry are derived from the idea that there is a lower overall Gibbs free energy due to the interaction between host and guest molecules. Chemists are exhaustively trying to measure the energy and thermodynamic properties of these non-covalent interactions found throughout supramolecular chemistry; and by doing so hope to gain further insight into the combinatorial outcome of these many, small, non-covalent forces that are used to generate an overall effect on the supramolecular structure.

In order to rationally and confidently design synthetic systems that perform specific functions and tasks, it is very important to understand the thermodynamics of binding between host and guest. Chemists are focusing on the energy exchange of different binding interactions and trying to develop scientific experiments to quantify the fundamental origins of these non-covalent interactions by utilizing various techniques such as NMR spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, isothermal titration calorimetry, surface tension,[3] and UV-Vis Spectroscopy. The experimental data are quantified and explained through analysis of binding constants Ka, Gibbs free energy ΔGo, Enthalpy ΔHo, and entropy ΔSo.[2]

Association and dissociation constants

The association constant, , is equal to the concentration of the host–guest complex divided by the product of the concentrations of the individual host and guest molecules when the system is in equilibrium.

The equilibrium that has been established between the host–guest complex and free molecules can also be defined by a dissociation constant, .

A Large value can be equated to a small , both values indicate a strong complexation between host and guest molecules to form the host–guest complex.

Gibbs free energy dependency on K

The Change in Gibbs free energy, ΔG, is a function of the equilibrium constant,

By knowing the association constant, the Gibbs free energy of the reaction can be solved.

- ,

One can also can see the dependency of Gibbs free energy on the macroscopic terms of enthalpy, ΔH and entropy, ΔS.

Experimental determination of [HG] using kinetics

In order to determine the concentration of the complex, one needs to write the equilibrium equation in terms that are able to be measured in the laboratory. Experimentally, one can determine the concentration of the host–guest complex, , as a function of the initial concentration of the guest molecules, .

Their occurs a problem because our association constant, which one wants to relate to the Gibbs free energy of the system, is a function of the concentration of host, and guest,, molecules at equilibrium. Therefore, in order to be able to successfully determine the as a function of , one must make some assumptions. These assumptions are necessary because the one only knows the initial concentrations of host and guest, and

In order to overcome this obstacle, one can first make the alternative equilibrium approximation which states that the initial concentration of host molecules, is equivalent to the concentration of both and ; this is because sum of all is only found in and

in terms of and :

Solving for yields:

This can be substituted into the original equilibrium equation

In solving for , one can determine that:

- At this point, we have gotten the concentration of complex in terms of the initial concentration of host molecules,

Another assumption that is made in the determination of as a function of and is that by setting the initial concentration of the Guest molecules, , much greater than the initial concentration of Host molecules, ; one can then say that:

- because:

- then:

With this final substitution, one can solve for the concentration of the host–guest complex as a function of the initial concentrations of the host and guest molecules:

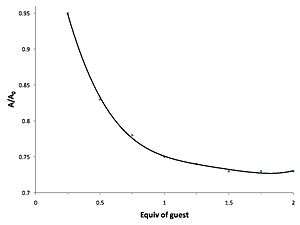

The final equation follows the form of the graph seen above. The plot above is called a binding isotherm which represents saturation kinetics and can be taken in two major parts.

At low concentrations of , (1>>>) the plot become linear as a function of .

- becomes:

- This is represented in the plot by the increasing linear portion of the curve.

At high concentrations of , then becomes independent of and the plot becomes a flat line again like seen in the very beginning of the curve.

The plot becomes independent of because when([G]o>>>1):

- becomes:

- This function is independent of the so thus the plot flattens out

This binding isotherm is one type of experimental data that can be analyzed and quantified by various spectroscopic imaging techniques; among others are Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Raman Spectroscopy, and isothermal titration calorimetry. These spectroscopic methods can be help the scientist quantify the thermodynamic principles of host–guest chemistry.

Quantifying host–guest chemistry

Nuclear magnetic resonance

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is one of the most powerful spectroscopic techniques in analytical chemistry. It is an important tool for the studies of host–guest complexes, for elucidating the structures of the various complexes existing in the form of aggregates, ion pair or encapsulated systems. As the name suggests, NMR identifies the different nuclei in the molecules (most commonly, proton), by measuring their chemical shift. The binding activity of two molecules causes a considerable change in their electronic environments. This leads to a shift in the signals in the NMR spectrum, and this basic principle is made use of to study the phenomena of host–guest chemistry. The driving forces for host–guest binding are the various secondary interactions between molecules, such as hydrogen bonding and pi-pi interaction. Thus, NMR also serves as an important technique to establish the presence of these interactions in a host–guest complex.<ref = name>Hu, J; Cheng, Y; Wu,Q; Zhao, L; Xu, T (2009). "Host–Guest Chemistry of Dendrimer-Drug Complexes. 2. Effects of Molecular Properties of Guests and Surface Functionalities of Dendrimers". J. Phys. Chem. B. 113 (31): 10650–10659. doi:10.1021/jp9047055.</ref>

Previous NMR studies have given useful information about the binding of different guest to hosts. Fox et al.[4] calculated the hydrogen-bond interactions between pyridine molecules and poly(amido amine (PAMAM) dendrimer; on the basis of the chemical shift of the amine and the amide groups. In a similar study, Xu et al.<ref = name/> titrated carboxylate based G4 PAMAM dendrimer (the host) with various amine based drugs (the guests) and monitored the chemical shifts of the dendrimer. In conjunction with the 2D-NOESY NMR techniques, they were able to precisely locate the position of the drugs on the dendrimers and the effect of functionality on the binding affinity of the drugs. They found conclusive evidence to show that the cationic drug molecules attach on the surface of anionic dendrimers by electrostatic interactions, whereas an anionic drug localizes both in the core and the surface of the dendrimers, and that the strength of these interactions are dependent on the pKa values of the molecules.

In a different study, Sun et al.[5] studied the host–guest chemistry of ruthenium trisbipyridyl-viologen molecules with cucurbituril. Whilst monitoring the change in the chemical shifts of the pyridine protons on viologen, they found that the binding modes for the 1:1 complexes are completely different for different cucurbituril molecules. In cucurbit[7]uril, only four aromatic protons per single bipyridyl ligand take part in the binding process, whilst all the aromatic protons of the ligand form a part of the complex when cucurbit[8]uril is used.

However, an important factor that has to be kept in mind while analyzing binding between the host and the guest is the time taken for data acquisition compared to the time for the binding event. In a lot of cases, the binding events are much faster than the time-scale of data acquisition, in which case the output is an averaged signal for the individual molecules and the complex. The NMR timescale is of the order of milliseconds, which in certain cases when the binding reaction is fast, limits the accuracy of the technique.[2]

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy is a spectroscopic technique used in the study of molecules which exhibit a Raman scattering effect when monochromatic light is incident on it. The basic requirement to get a Raman signal is that the incident light brings about an electronic transition in the chemical species from its ground state to a virtual energy state, which will emit a photon on returning to the ground state. The difference in energy between the absorbed and the emitted photon is unique for each chemical species depending on its electronic environment. Hence, the technique serves as an important tool for study of various binding events, as binding between molecules almost always results in a change in their electronic environment. However, what makes Raman spectroscopy a unique technique is that only transitions which are accompanied by a change in the polarization of the molecule are Raman active. The structural information derived from Raman spectra gives very specific information about the electronic configuration of the complex as compared to the individual host and guest molecules.

Solution-phase Raman spectroscopy often results in a weak scattering cross-section. Therefore, recent advances have been made to enhance the Raman signals, such as surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy, and Resonance Raman spectroscopy. Such techniques serve an additional purpose of quantifying the analyte-receptor binding events, giving a more detailed picture of the host–guest complexation phenomena where they actually take place; in solutions. In a recent breakthrough, Flood et al. determined the binding strength of tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) and cyclobis(paraquat-p-phenylene) using Raman spectroscopy[6] as well as SERS.[7] Prior work in this field was aimed at providing information on the bonding and the structure of the resulting complex, rather than quantitative measurements of the association strengths. The researchers had to use Resonance Raman spectroscopy in order to be able to get detectable signals from solutions with concentrations as low as 1 mM. In particular they correlated the intensity of the Raman bands with the geometry of the complex in the photo-excited state. Similar to UV-vis spectroscopy based titration; they calculated the binding constant by “Raman titration” and fitted the binding curves to 1:1 models, giving a of -5.7±0.6 kcal/mol. The study is now providing a basis for similar studies involving charge transfer complexes in solutions.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Spectroscopic techniques give information about the binding constant and Gibbs free energy, . To get the complete set of thermodynamic parameters such as and , a Van’t Hoff analysis using the Van 't Hoff equation would be required. However, recent advents in calorimetric techniques allows for the measurement of and in a single experiment, thus enabling determination of all the thermodynamic parameters using the equation:

provided that the experiment is carried out under isothermal conditions; hence the name isothermal calorimetry. The procedure is similar to a conventional titration procedure wherein the host is added sequentially to the guest and the heat absorbed or evolved is measured, compared to a blank solution. The total heat released, Q, corresponds to the association constant, , and by the equation:

Which can be simplified as

Where

- = Initial molar concentration of the host

- = Molar concentration of the guest

- = volume of the vessel

The above equation can be solved by non-linear regression analysis to obtain the value of and and subsequently and for that particular reaction.[2] The advantages of isothermal titration calorimetry over the other commonly used techniques, apart from giving the entire set of thermodynamic parameters, are that it is more general and suited for a wide range of molecules. It is not necessary to have compounds with chromophores or UV-visible functional groups in order to monitor the binding process as the heat signal is a universal property of binding reactions. At the same time, the signal to noise ratio is pretty favorable which allows for more accurate determination of the binding constants, even under very dilute conditions.[8] A recent example of the use of this technique was for studying the binding affinity of the protein membrane surrounding Escherichia coli to lipophilic cations used in drugs in various membrane mimetic environments. The motivation for the above study was that these membranes render the bacteria resistant to most quaternary ammonium cation based compounds which have the anti-bacterial effects. Thus an understanding of the binding phenomena would enable design of effective antibiotics for E. coli. The researchers maintained a large excess of the ligand over the protein to allowing the binding reaction to go to completion. Using the above equations the researchers proceeded to calculate , , and for each drug in different environments. The data indicated that the binding stoichiometry of the drug with the membrane was 1:1 with a micromolar value of . The negative values of , and indicated that the process was enthalpy driven with a value of 8-12 kcal/mol for each drug.[9]

UV-vis spectroscopy

UV-vis spectroscopy is one of the oldest and quickest methods of studying the binding activity of various molecules. The absorption of UV-light takes place at a time-scale of picoseconds, hence the individual signals from the species can be observed. At the same time, the intensity of absorption directly correlates with the concentration of the species, which enables easy calculation of the association constant.[2] Most commonly, either the host or the guest is transparent to UV-light, whilst the other molecule is UV-sensitive. The change in the concentration of the UV-sensitive molecules is thus monitored and fitted onto a straight line using the Benesi-Hildebrand method, from which the association constant can be directly calculated. Additional information about the stoichiometry of the complexes is also obtained, as the Benesi-Hilderbrand method assumes a 1:1 stoichiometry between the host and the guest. The data will yield a straight line only if the complex formation also follows a similar 1:1 stoichiometry. A recent example of a similar calculation was done by Sun et al.,[5] wherein they titrated ruthenium trisbipyridyl-viologen molecules with cucurbit[7]urils and plotted the relative absorbance of the cucurbit molecules as a function of its total concentration at a specific wavelength. The data nicely fitted a 1:1 binding model with a binding constant of . As an extension, one can fit the data to different stoichiometries to understand the kinetics of the binding events between the host and the guest.[10] made use of this corollary to slightly modify the conventional Benesi-Hilderbrand plot to get the order of the complexation reaction between barium-containing crown ether bridged chiral heterotrinuclear salen Zn(II) complex (host) with various guests imidazoles and amino acid methyl esters, along with the other parameters. They titrated a fixed concentration of the zinc complex with varying amounts of the imidazoles and methyl esters whilst monitoring the changes in the absorbance of the pi to pi* transition band at 368 nm. The data fit a model in which the ratio of guest to host of 2 in the complex. They further carried these experiments at various temperatures which enabled them to calculate the various thermodynamic parameters using the Van 't Hoff equation.

Applications of host–guest chemistry

Cooperativity

Cooperativity is defined to be when a ligand binds to a receptor with more than one binding site, the ligand causes a decrease or increase in affinity for incoming ligands. If there is an increase in binding of the subsequent ligands, it is considered positive cooperativity. If a decrease of binding is observed, then it is negative cooperativity. Examples of positive and negative cooperativity are hemoglobin and aspartate receptor, respectively.[11]

In recent years, the thermodynamic properties of cooperativity have been studied in order to define mathematical parameters that distinguish positive or negative cooperativity. The traditional Gibbs free energy equation states: . However, to quantify cooperativity in a host–guest system, the binding energy needs to be considered. The schematic on the right shows the binding of A, binding of B, positive cooperative binding of A–B, and lastly, negative cooperative binding of A–B. Therefore, an alternate form of the Gibbs free energy equation would be

where:

- = free energy of binding A

- = free energy of binding B

- = free energy of binding for A and B tethered

- = sum of the free energies of binding

It is considered that if more than the sum of and ,it is positively cooperative. If is less, then it is negatively cooperative.[12] Host–guest chemistry is not limited to receptor-lingand interactions. It is also demonstrated in ion-pairing systems. In recent years, such interactions are studied in an aqueous media utilizing synthetic organometallic hosts and organic guest molecules. For example, a poly-cationic receptor containing copper (the host) is coordinated with molecules such as tetracarboxylates, tricarballate, aspartate, and acetate (the guests). This study illustrates that entropy rather than enthalpy determines the binding energy of the system leading to negative cooperativity. The large change in entropy originates from the displacement of solvent molecules surrounding the ligand and the receptor. When multiple acetates bind to the receptor, it releases more water molecules to the environment than a tetracarboxylate. This led to a decrease in free energy implying that the system is cooperating negatively.[13] In a similar study, utilizing guanidinium and Cu(II) and polycarboxylate guests, it is demonstrated that positive cooperatively is largely determined by enthalpy.[14] In addition to thermodynamic studies, host–guest chemistry also has biological applications.

Biological application

Dendrimers in drug-delivery system is an example of various host–guest interactions. The interaction between host and guest, the dendrimer and the drug, respectively, can either be hydrophobic or covalent. Hydrophobic interaction between host and guest is considered “encapsulated,” while covalent interactions are considered to be conjugated. The use of dendrimers in medicine has shown to improve drug delivery by increasing the solubility and bioavailability of the drug. In conjunction, dendrimers can increase both cellular uptake and targeting ability, and decrease drug resistance.[15]

The solubility of various NSAIDs increases when it is encapsulated in PAMAM dendrimers.[16] This study shows the enhancement of NSAID solubility is due to the electrostatic interactions between the surface amine groups in PAMAM and the carboxyl groups found in NSAIDs. Contributing to the increase in solubility are the hydrophobic interactions between the aromatic groups in the drugs and the interior cavities of the dendrimer.[17] When a drug is encapsulated within a dendrimer, its physical and physiological properties remains unaltered, including non-specificity and toxicity. However, when the dendrimer and the drug are covalently linked together, it can be used for specific tissue targeting and controlled release rates.[18] Covalent conjugation of multiple drugs on dendrimer surfaces can pose a problem of insolubility.[18][19]

This principle is also being studied for cancer treatment application. Several groups have encapsulated anti-cancer medications such as: Camptothecin, Methotrexate, and Doxorubicin. Results from these research has shown that dendrimers have increased aqueous solubility, slowed release rate, and possibly control cytotoxicity of the drugs.[15] Cisplatin has been conjugated to PAMAM dendrimers that resulted in the same pharmacological results as listed above, but the conjugation also helped in accumulating cisplatin in solid tumors in intravenous administration.[20]

Sensing

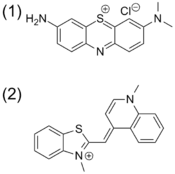

Traditionally, chemical sensing has been approached with a system that contains a covalently bound indicator to a receptor though a linker. Once the analyte binds, the indicator changes color or fluoresces. This technique is called the indicator-spacer-receptor approach (ISR).[21] In contrast to ISR, Indicator-Displacement Assay (IDA) utilizes a non-covalent interaction between a receptor (the host), indicator, and an analyte (the guest). Similar to ISR, IDA also utilizes colorimetric (C-IDA) and fluorescence (F-IDA) indicators. In an IDA assay, a receptor is incubated with the indicator. When the analyte is added to the mixture, the indicator is released to the environment. Once the indicator is released it either changes color (C-IDA) or fluoresces (F-IDA).[22]

IDA offers several advantages versus the traditional ISR chemical sensing approach. First, it does not require the indicator to be covalently bound to the receptor. Secondly, since there is no covalent bond, various indicators can be used with the same receptor. Lastly, the media in which the assay may be used is diverse.[23]

Chemical sensing techniques such as C-IDA have biological implications. For example, protamine is a coagulant that is routinely administered after cardiopulmonary surgery that counter acts the anti-coagulant activity of herapin. In order to quantify the protamine in plasma samples, a colorimetric displacement assay is used. Azure A dye is blue when it is unbound, but when it is bound to herapin, it shows a purple color. The binding between Azure A and heparin is weak and reversible. This allows protamine to displace Azure A. Once the dye is liberated it displays a purple color. The degree to which the dye is displaced is proportional to the amount of protamine in the plasma.[24]

F-IDA has been used by Kwalczykowski and co-workers to monitor the activities of helicase in E.coli. In this study they used thiazole orange as the indicator. The helicase unwinds the dsDNA to make ssDNA. The fluorescence intensity of thiazole orange has a greater affinity for dsDNA than ssDNA and its fluorescence intensity increases when it is bound to dsDNA than when it is unbound.[25]

Conformational switching

A crystalline solid has been traditionally viewed as a static entity where the movements of its atomic components are limited to its vibrational equilibrium. As seen by the transformation of graphite to diamond, solid to solid transformation can occur under physical or chemical pressure. It has been recently proposed that the transformation from one crystal arrangement to another occurs in a cooperative manner.[26][27] Most of these studies have been focused in studying an organic or metal-organic framework.[28][29] In addition to studies of macromolecular crystalline transformation, there are also studies of single-crystal molecules that can change their conformation in the presence of organic solvents. An organometallic complex has been shown to morph into various orientations depending on whether it is exposed to solvent vapors or not.[30]

Environmental applications

Host guest systems have been utilized to remove hazardous materials from the environment. They can be made in different sizes and different shapes to trap a variety of chemical guests. One application is the ability of p-tert-butycalix[4]arene to trap a cesium ion. Cesium-137 is radioactive and there is a need to remove it from nuclear waste in an efficient manner. Guest-host chemistry has also been used to remove carcinogenic aromatic amines, and their N-nitroso derivatives from water. These waste materials are used in many industrial processes and found in a variety of products such as: pesticides, drugs, and cosmetics.[31][32]

References

- ↑ Lodish, H.; Berk, A.; Kaiser, C. (2008). Molecular Cell Biology. ISBN 978-0-7167-7601-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anslyn, Eric (2006). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3.

- ↑ Piñeiro, Á.; Banquy, X.; Pérez-Casas, S.; Tovar, É.; García, A.; Villa, A.; Amigo, A.; Mark, A. E.; Costas, M. (2007). "On the Characterization of Host–Guest Complexes: Surface Tension, Calorimetry, and Molecular Dynamics of Cyclodextrins with a Non-ionic Surfactant". J. Phys. Chem. B. 111 (17): 4383–92. doi:10.1021/jp0688815. PMID 17428087.

- ↑ Santo, M; Fox, M (1999). "Hydrogen bonding interactions between Starburst dendrimers and several molecules of biological interest". Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry. 12 (4): 293–307. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1395(199904)12:4<293::AID-POC88>3.0.CO;2-Q.

- 1 2 Sun, S; Zhang, R; Andersson, S; Pan, J; Zou, D; Åkermark, Björn; Sun, Licheng (2007). "Host–Guest Chemistry and Light Driven Molecular Lock of Ru(bpy)3-Viologen with Cucurbit[7-8]urils". J. Phys. Chem. B. 111 (47): 13357–13363. doi:10.1021/jp074582j.

- ↑ Witlicki, Edward H.; et al. (2009). "Determination of Binding Strengths of a Host–Guest Complex Using Resonance Raman Scattering". J. Phys. Chem. A. 113 (34): 9450–9457. doi:10.1021/jp905202x.

- ↑ Witlicki, Edward H.; et al. (2010). "Turning on Resonant SERRS Using the Chromophore-Plasmon Coupling Created by Host–Guest Complexation at a Plasmonic Nanoarray". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (17): 6099–6107. doi:10.1021/ja910155b.

- ↑ Brandts; et al. (1989). "Rapid measurements of Binding Constants and Heats of binding Using a New Titration Calorimeter". Analytical Biochemistry (journal). 179: 131–137. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3.

- ↑ Sikora, C; Turner, R (2005). "Investigation of Ligand Binding to the Multidrug Resistance Protein EmrE by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry". Biophysical Journal. 88 (1): 475–482. Bibcode:2005BpJ....88..475S. doi:10.1529/biophysj.104.049247. PMC 1305024

. PMID 15501941.

. PMID 15501941. - ↑ Zhu; et al. (1989). "Spectroscopy, NMR and DFT studies on molecular recognition of crown ether bridged chiral heterotrinuclear salen Zn(II) complex". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 62 (4–5): 886–895. Bibcode:2005AcSpA..62..886G. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2005.03.021.

- ↑ Koshland, D (1996). "The structural basis of negative cooperativity: receptors and enzymes". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 6 (6): 757–761. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(96)80004-2. PMID 8994875.

- ↑ Jencks, W. P. (1981). "On the attribution and additivity of binding energies". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78 (7): 4046–4050. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.4046J. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.7.4046. PMC 319722

. PMID 16593049.

. PMID 16593049. - ↑ Dobrzanska, L; Lloyd, G; Esterhuysen, C; Barbour, L (2003). "Studies into the Thermodynamic Origin of Negative Cooperativity in Ion-Pairing Molecular Recognition". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 (36): 10963–10970. doi:10.1021/ja030265o.

- ↑ Hughes, A.; Anslyn, E (2007). "A cationic host displaying positive cooperativity in water". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (16): 6538–6543. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6538H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609144104. PMC 1871821

. PMID 17420472.

. PMID 17420472. - 1 2 Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Rao, T.; He, X.; Xu, T. (2008). "Pharmaceutical applications of dendrimers: promising nanocarriers for drug discovery". Frontiers in Bioscience. 13 (13): 1447–1471. doi:10.2741/2774.

- ↑ Cheng, Y.; Xu, T. (2005). "Dendrimers as Potential Drug Carriers. Part I. Solubilization of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in the Presence of Polyamidoamine Dendrimers". Eur. J. Med. Chem. 40 (11): 1188–1192. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.06.010.

- ↑ Cheng, Y.; Xu, T; Fu, R (2005). "Polyamidoamine dendrimers used as solubility enhancers of ketoprofen". Eur. J. Med. Chem. 40 (12): 1390–1393. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.08.002.

- 1 2 Cheng, Y.; Xu, Z; Ma, M.; Xu, T. (2007). "Dendrimers as drug carriers: Applications in different routes of drug administration". J. Pharm. Sci. 97: 123–143. doi:10.1002/jps.21079.

- ↑ D’Emanuele, A; Attwood, D (2005). "Dendrimer–drug interactions". Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 57 (15): 2147–2162. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2005.09.012.

- ↑ Malik, N.; Evagorou, E.; Duncan, R. (1999). "Dendrimer-platinate: a novel approach to cancer chemotherapy". Anti-cancer Drugs. 10 (8): 767–776. doi:10.1097/00001813-199909000-00010. PMID 10573209.

- ↑ de Silva, A.P.; McCaughan, B; McKinney, B.O. F.; Querol, M. (2003). "Newer optical-based molecular devices from older coordination chemistry". Dalton Trans. 10 (10): 1902–1913. doi:10.1039/b212447p.

- ↑ Anslyn, E. (2007). "Supramolecular Analytical Chemistry". J. Org. Chem. 72 (3): 687–699. doi:10.1021/jo0617971. PMID 17253783.

- ↑ Nguyen, B.; Anslyn, E. (2006). "Indicator-displacement assays". Coor. Chem. Rev. 250 (23–24): 3118–3127. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.009.

- ↑ Yang, V.; Fu, Y.; Teng, C.; Ma, S.; Shanberge, J. (1994). "A method for the quantitation of protamine in plasma". Thromb. Res. 74 (4): 427–434. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(94)90158-9. PMID 7521974.

- ↑ Eggleston, A.; Rahim, N.; Kowalczykowski, S; Ma, S.; Shanberge, J. (1996). "A method for the quantitation of protamine in plasma". Nucleic Acids Research. 24 (7): 1179–1186. doi:10.1093/nar/24.7.1179.

- ↑ Atwood, J; Barbour, L; Jerga, A; Schottel, L (2002). "Guest Transport in a nonporous Organic Solid via Dynamic van der Waals Cooperativity". Science. 298 (5595): 1000–1002. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.1000A. doi:10.1126/science.1077591. PMID 12411698.

- ↑ Kitagawa, S; Uemura, K (2005). "Dynamic porous properties of coordination polymers inspired by hydrogen bonds". Chem. Soc. Rev. 34 (2): 109–119. doi:10.1039/b313997m.

- ↑ Sozzani, P; Bracco, S; Commoti, A; Ferretti, R; Simonutti, R (2005). "Methane and Carbon Dioxide Storage in a Porous van der Waals Crystal". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44 (12): 1816–1820. doi:10.1002/anie.200461704. PMID 15662674.

- ↑ Uemura, K; Kitagawa, S; Fukui, K; Saito, K (2004). "A Contrivance for a Dynamic Porous Framework: Cooperative Guest Adsorption Based on Square Grids Connected by Amide−Amide Hydrogen Bonds". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (12): 3817–3828. doi:10.1021/ja039914m. PMID 15038736.

- ↑ Dobrzanska, L; Lloyd, G; Esterhuysen, C; Barbour, L (2006). "Guest-Induced Conformational Switching in a Single Crystal". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45 (35): 5856–5859. doi:10.1002/anie.200602057. PMID 16871642.

- ↑ Eric Hughes; Jason Jordan; Terry Gullion (2001). "Structural Characterization of the [Cs(p-tert-butylcalix[4]arene -H) (MeCN)] Guest-Host System by 13C-133Cs REDOR NMR". J. Phys. Chem. B. 105 (25): 5997–5891. doi:10.1021/jp004559x.

- ↑ Serkan Erdemir; Mufit Bahadir; Mustafa Yilmaz (2009). "Extraction of Carcinogenic Aromatic Amines from Aqueous Solution Using Calix[n]arene Derivatives as Carriers". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 168 (2–3): 1170–1176. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.02.150. PMID 19345489.