History of rail in Oregon

The history of rail in Oregon predates the transcontinental railroad in 1869.[1]

As Oregon was aligned with the union states during the American Civil War, a railroad connection was proposed to help supply the Union and build morale.[1]

Early proposals

Byron J. Pengra, the Surveyor General of Oregon from 1862 to 1865, secured a federal land grant in 1864 for the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road from Eugene to Owyhee, and proposed a railroad along this line, then joining the transcontinental railroad near Winnemucca, Nevada. Pengra incorporated a company in 1867 but failed due to lack of financial support.[1]

William Williams Chapman, Surveyor General of Oregon from 1857 to 1861, proposed a railroad along the Oregon Trail from Portland, over the Blue Mountains, along the Snake River, then south to the transcontinental railroad at Salt Lake City. Chapman created the Portland, Dalles and Salt Lake Railroad Company in 1881, then reincorporated it as the Portland, Salt Lake and Salt Pass Railroad Company in 1876. He attempted to raise funds for this company in the eastern United States as well as England.[1]

Both Pengra and Chapman's companies were hampered by the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal in 1872.[1]

Rail routes to follow the Oregon Trail were surveyed by the government, Union Pacific, and others, including James H. Slater and Dan Chapman's Grande Ronde Valley and Columbia River Valley Construction Company in 1874, and the Blue Mountain and Columbia River Rail-Road Company's narrow gauge effort.[1]

The wooden-railed narrow-gauge Walla Walla and Columbia River Railroad, established in 1868, involved several overland portages.[1]

Henry Villard

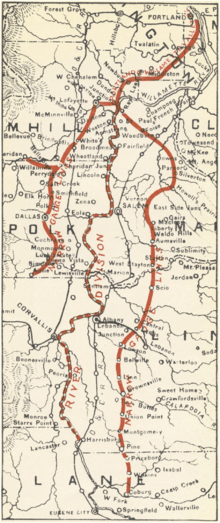

Henry Villard was sent by German investors to see oversee their investments in the Oregon and California Railroad Company, then became the major force in railroading for the region. In 1879, he purchased the Oregon Steam Navigation Company and the Oregon Steamship Company, merging them to the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (OR&N).[1]

Since Union Pacific and Central Pacific had an uneasy agreement due to owning the western and eastern halves of the Transcontinental Railroad, Vilard approached Union Pacific with an alternative to using the Central Pacific line from Salt Lake City to San Francisco. He offered a 50% partnership in the OR&N in 1879. Union was already building an extension from Brigham City, Utah to Butte, Montana that could be extended west. Central Pacific threatened Union Pacific if such an arrangement was made, which ended it immediately.[1]

Northern Pacific had a line reaching from the Dakotas to northern Idaho. Villard reached an agreement with Northern Pacific in 1880, which gave Portland access to transcontinental rail lines. Since activity in the Pacific Northwest had picked up by 1881, Union Pacific was again interested in the 1879 proposal. Union Pacific created the Oregon Short Line from Granger, Wyoming to the OR&N lines at Huntington, Oregon, joined on November 11, 1884.[1][2] Union Pacific and Northern Pacific were now in direct competition, which led Northern Pacific to build their own line directly to the coast at Tacoma, Washington.[1]

Villard's OR&N lines were leased to Union Pacific's Oregon Short Line from 1887 until Union Pacific purchased OR&N in 1889.[1]

Planned or incomplete railroad lines

The following railroad lines were surveyed and perhaps graded, but not completed.

Northeast Oregon

- Union, Cornucopia and Eastern Railway (or UCE) - planned to connect Union, Oregon with mines near Cornucopia, $3 million in funds[1]

- Union, Cove and Valley Railway - planned to use the Union depot of the UCE to Cove[1]

- Union, Cornucopia and Eastern Transportation Company - planned to build on the same route of the planned UCE. November, 1898, $3.5 million in funds, had a Chinese-American director, unusual in the 1890s.[1]

- Summerville, Blue Mountain and Walla Walla Railroad Company - planned to follow the former Thomas and Ruckle Road from Summerville to Walla Walla. Fall 1898.[1]

- Union Railroad and Transportation Company, renamed Union Railroad Company. Planned to follow the UCE to the Snake River.

- Hilgard, Granite and Southwestern - originate on the OR&N line near Hilgard and connect to Granite to supply the Powder River Mines.[1]

- Grande Ronde and Wallowa Railway Company - follow the Grande Ronde River to connect Elgin, Wallowa, and Joseph.[1]

- Oregon Washington Railroad Company - G. W. Hunt, January 1889 intended to run from Weston across the Blue Mountains, eventually to Boise. Company purchased by 1891, never completed in part due to the Panic of 1893.[1]

- Wallowa Valley Railroad Company, W. J. Cook, 1905 attempt to connect Elgin to Lewiston, Idaho. OR&N completed their line as far as Elgin once they discovered this attempt, but never completed the Lewiston segment.[1]

Completed railroad lines

- Central Railway of Oregon - purchased existing rail lines near Union, Oregon and built an extension from Union to Cove in 1906. Went bankrupt in 1909, reformed as Central Railroad of Oregon in the same year. Surveyed lines across the Blue Mountains in 1910, actually built a 4-mile (6.4 km) line from Richmond to a Hot Lake Hotel. Hauled 33,415 passengers and 18,200 tons of freight in 1912, but went out of business in 1924. All rail lines were scrapped, except for the Union-Union Junction segment, which was taken over by the Union Railroad of Oregon, which was in service (especially for the Ronde Valley Lumber Company) at least into the 1970s.[1]

See also

- Rail transportation in Oregon

- List of Oregon railroads

- Oregon Rail Heritage Foundation

- Oregon land fraud scandal

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Deumling, Dietrich (May 1972). The roles of the railroad in the development of the Grande Ronde Valley (masters thesis). Flagstaff, Arizona: Northern Arizona University. OCLC 4383986.

- ↑ Meinig, D. W. (1968). The Great Columbia Plain: A Historical Geography, 1805-1910. University of Washington Press. pp. 260–261. OCLC 436410.