Crédit Mobilier of America scandal

The Crédit Mobilier scandal of 1867, which came to public attention in 1872, involved the Union Pacific Railroad and the Crédit Mobilier of America construction company in the building of the eastern portion of the First Transcontinental Railroad. The scandal was in two parts. The construction company charged the railroad far higher rates than usual, and cash and $9 million in discounted stock were given as bribes to 15 powerful Washington politicians, including the Vice-President, the Secretary of the Treasury, four senators, and the Speaker and other members of the House.[1]

The scandal's origins dated back to 1864 when the Union Pacific Railroad was chartered by Congress and the associated Crédit Mobilier was established. (This company had no relation to the French bank of the same name, at the time one of major financial institutions in the world). In 1867, Congressman Oakes Ames distributed cash bribes and discounted shares of Crédit Mobilier stock to other congressmen in exchange for votes and actions favorable to the Union Pacific.[2] The story was broken by the New York newspaper, The Sun, during the 1872 presidential campaign, when Ulysses S. Grant was running for re-election.[3] Included in the group of legislators named as having received cash or discounted shares of stock were: former Representative Schuyler Colfax, then serving as Grant's Vice President; Henry Wilson, the senator selected to replace Colfax as the Republican vice presidential nominee during the 1872 Presidential election; James G. Blaine, then-Speaker of the House; and Representative James Garfield, the future president of the United States. The scandal caused widespread public distrust of Congress and the federal government during the Gilded Age.

Background

The federal government in 1864–1868 had authorized and chartered the Union Pacific Railroad with $100 million capital, to complete a transcontinental line west from the Missouri River to the Pacific coast. The federal government offered to assist the railroad with a loan of $16,000 to $48,000 per mile, according to location, for a total of more than $60,000,000 in all, and a land grant of 20,000,000 acres, worth $50,000,000 to $100,000,000. The offer initially attracted no subscribers for financing, as the conditions were financially daunting.

Virtually the entire right-of-way (ROW) from the Missouri river to the California coast was without any freight or passenger traffic demand; as there were no commercial activities of any kind nor was there any commerce between the then non-existent cities or towns from Nebraska to the California border. Nor were there any branch lines running either to the north or south of the proposed ROW that would have been able to expand their branch traffic by connection with the future transcontinental railway. And finally (contrary fiscal reality), the entire railroad scheme was being proposed as a "going concern"; that is, as a financially viable idea which; with only "below market" financing, could, both be successfully built; and, thereafter (as a going business and functioning business enterprise) earn, thru freight and passenger rail revenues, its operating expenses; profits for investors; interest payments (to the US) on the borrowed U.S, government capital (at the Federal funds rate, based upon the US government bond rates); and ultimately; the retirement of the debt to the U.S. government. Private capital recognized that this proposed model, its objectives and economic projections, were an impossibility (the traffic demand could never generate freight or passenger revenues sufficient to maintain the ROW, motive power (locomotives), freight & passenger rolling stock; and, to retire the debt due to construction and operations. So, on that basis private investors didn't invest.

The railroad would have to be built for 1,750 miles through desert and mountain, which would mean extremely high freight costs for supplies. In addition, there was the likely risk of armed conflict with hostile tribes of Indians, who occupied many territories in the interior, and no probable early business to pay dividends.[4]

George Francis Train and Thomas C. Durant, who was vice president of the Union Pacific Railroad at the time, formed the Crédit Mobilier in 1864. The original company, Pennsylvania Fiscal Agency, was a loan and contract company chartered in 1859.[4] The creation of Crédit Mobilier of America was a deliberate attempt to falsely present to the government of the United States and to the general public the appearance that a corporate enterprise (independent of the Union Pacific Railroad and its principal officers) had been impartially chosen by the Union Pacific Railroad's officers and directors to be the principal construction contractor and construction management firm for the Union Pacific Railroad project. It was created by the officers of the Union Pacific to shield the companies' shareholders and management from the then common charge that they were using the construction phase of the Union Pacific project (as opposed to the operating phase of carrying passengers and freight) to line their pockets with excess profits. The fraudsters believed that profits could not be generated from the operation of the railroad, so they created a sham company to charge the U.S. government extortionate fees and expenses during construction of the line.

In simplified terms, the Crédit Mobilier fraud worked in the following manner: The Union Pacific made contracts with Crédit Mobilier to build the Union Pacific railway at rates significantly above cost. These construction contracts brought high profits to the Crédit Mobilier, which was owned by Durant and the Union Pacific's other directors and principal stockholders, and which split the outsize profits with the Union Pacific stockholders. The directors of the Union Pacific were also able to circumvent rules requiring them to receive full payment for stock issued at par, by paying Crédit Mobilier for construction contracts in bank checks, which Crédit Mobilier then used to purchase Union Pacific stock at par.[5]

The net result was that the U.S. Congress paid $94,650,287 to Crédit Mobilier via Union Pacific while Crédit Mobilier incurred operating costs of only $50,720,959. Thus the deal generated $43,929,328 in profits for Crédit Mobilier, counting at par value the Union Pacific shares and bonds that Crédit Mobilier bought and paid itself.[4] The Crédit Mobilier directors reported this as a cash profit of only $23,366,319.81, a financial misrepresentation; since these same directors in fact were also the recipients of the undisclosed $20,563,010, Union Pacific share of the $44 million in total profits.[4][6]

If the Union Pacific's corporate officers had openly undertaken the management and construction of the railroad, this scheme (to make windfall profits immediately from charges made during construction) would have been exposed to public scrutiny from the start. It would have proved that the opponents of the Pacific Railroad Act had from the beginning been right: the western transcontinental railroad scheme was an unprofitable venture. The opponents had from the start believed the whole project was a bare-faced fraud by some capitalists to build a "railroad to nowhere" and to make tremendous profits doing so, all the while getting the United States government to pay for it. The opponents also thought the construction and its routing were being developed without regard for trying to create a viable and profitable transportation enterprise when the railroad line was completed.

The principal means of the fraud was the method of indirect billing. The Union Pacific presented genuine and accurate invoices to the U.S. government, as evidence of actual construction costs incurred and billed to them by Crédit Mobilier of America for payment. The railroad then prepared and presented meticulously detailed invoices to the U.S. government, requesting payment for these bills, accrued by the Union Pacific from Crédit Mobilier, for the construction of the line. The bills reflected only a small additional fee over the cost stated on the Crédit Mobilier invoices for the Union Pacific's operating and overhead expenses, incurred during the line's construction a time when no traffic (freight or passenger) was being carried.

Any audit of the Union Pacific and its invoices to the U.S. government would have revealed no evidence of fraud or profiteering. Union Pacific was accepting for payment genuine Crédit Mobilier invoices and was applying an auditable overhead expense for management and administration (of the Union Pacific) during construction of the railroad.

The underlying fraud of a common and unified ownership of the two companies, as regards their principal officers and directors, was not revealed for years. Nor was it revealed that in every major construction contract drawn up between the Union Pacific and Crédit Mobilier, the contract's terms, conditions, and price had been offered (by Crédit Mobilier) and accepted (by the Union Pacific) through the actions of corporate officers and directors who were one and the same persons. The company sought, and was largely successful, in maintaining this fraud and its secrecy by giving discounted (well below the market value, of this highly profitable company) shares of stock (in Crédit) to those members of Congress who also agreed to support additional funding for the railroad. Because of its excessive charges for building the line, the company fully expected that the Union Pacific would have to return to Congress to gain appropriation of additional construction funds. For its time, it was a very sophisticated corporate scam, and it was, at the time, mostly legal.

Transgression

In 1867, Crédit Mobilier replaced Thomas Durant as its head with the Congressman Oakes Ames.[7] In that year Ames offered to members of Congress shares of stock in Crédit Mobilier at its discounted par value rather than the market value, which was much higher. The high market value of the stock resulted from the superb performance of Crédit Mobilier of America as a corporation, which in turn succeeded due to its major contract with the Union Pacific. Crédit Mobilier was the exclusive construction and management agent for the building of the Pacific Railroad. The Union Pacific "suspected" no wrongdoing, and they "paid" Crédit Mobilier (actually themselves) whatever "they" were asked to pay. Crédit Mobilier's corporate income statement regularly showed high revenues in excess of its expenses, and very high net profits in every quarter that it was engaged in the construction of the railroad. It also declared substantial quarterly dividends on its stock.

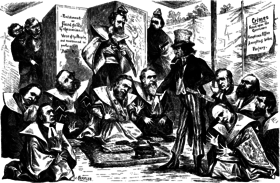

The congressmen and others allowed to purchase shares at a discount could reap enormous capital gains simply by offering their shares on the market, knowing that they would be purchased at a higher price by investors desiring to own stock in such a "profitable" company. These same members of Congress made the company appear to be profitable by voting to appropriate government funds to cover Crédit Mobilier's inflated charges. Ames' actions became one of the best-known examples of graft in American history.

During the 1872 presidential campaign, the New York City newspaper, The Sun, broke the story.[8] The paper opposed the re-election of Ulysses S. Grant and was regularly publishing articles critical of his administration. Following a disagreement with Ames, Henry Simpson McComb, an associate of Ames' and a later executive of the Illinois Central Railroad, leaked compromising letters to the newspaper. The Sun reported that Crédit Mobilier had received $72 million in contracts for building a railroad worth only $53 million. After the revelations, the Union Pacific and other investors were left nearly bankrupt.[7]

Investigation and outcome

In 1872, the House of Representatives submitted the names of nine politicians to the Senate for investigation: Senators William B. Allison (R-IA), James A. Bayard, Jr. (D-DE), George S. Boutwell (R-MA), Roscoe Conkling (R-NY), James Harlan (R-IA), John Logan (R-IL), James W. Patterson (R-NH), and Henry Wilson (R-MA), and Vice President Schuyler Colfax (R-IN). Bayard wrote a letter disavowing any knowledge of the affair, and his name was generally dropped from the investigation.[9]

Ultimately, Congress investigated 13 of its members in a probe that led to the censure of Ames and James Brooks, a Democrat from New York. A Department of Justice investigation was also made, with Aaron F. Perry serving as chief counsel. During the investigation, the government found that the company had given shares to more than 30 representatives of both parties, including James A. Garfield, Colfax, Patterson, and Wilson.

Garfield denied the charges and succeeded in gaining election as President in 1880, so the scandal did not have much effect on him. The Republicans replaced Colfax on the ticket, ending his bid to be renominated for Vice President. The new candidate, Henry Wilson, had also been implicated. However, Wilson was able to show that he had paid for stock in his wife's name, and with her money. When the Wilsons later had concerns about the transaction, Ames returned the purchase price, and Wilson returned the dividends he had been paid, while also paying his wife the amount she would have received as dividends if she had kept the stock.[10]

In popular culture

This scheme was dramatized in the AMC television series Hell on Wheels, beginning with the November 6, 2011 pilot episode.

See also

- Crédit Mobilier, a bank in France that had no connection

- Grantism

References

- ↑ James Ford Rhodes, History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Final Restoration of Home Rule at the South in 1877: 1872-1877. Vol. 7 (1916) pp 1-19.

- ↑ "WGBH American Experience . Transcontinental Railroad | PBS". American Experience. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- ↑ "The Crédit Mobilier Scandal | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- 1 2 3 4

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Crédit Mobilier of America". Encyclopedia Americana.

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Crédit Mobilier of America". Encyclopedia Americana. - ↑ White, Richard (2011). Railroaded: the Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-393-34237-6.

- ↑ Ambrose, Stephen E. (2001). Nothing Like It in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869. New York, N.Y.: Simon & Schuster. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-405-13762-4.

- 1 2 Trent, Logan Douglas (1981). The Credit Mobilier. New York, New York: Arno Press Inc. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-405-13762-4.

- ↑ "The King Of Frauds: How the Credit Mobilier Bought Its Way Through Congress". The Sun. New York. 1872-09-04.

- ↑ "The Expulsion Case of James W. Patterson of New Hampshire (1873) (Crédit Mobilier Scandal)". U.S. Senate Historical Office. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ↑ Crawford, Jay Boyd (1880). The Credit Mobilier of America: Its Origin and History. Boston, MA: C. W. Calkins & Co. p. 126.

Further reading

- Green, Fletcher M. "Origins of the Credit Mobilier of America." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 46.2 (1959): 238-251. in JSTOR

- Kens, Paul. "The Crédit Mobilier Scandal and the Supreme Court: Corporate Power, Corporate Person, and Government Control in the Mid‐nineteenth Century." Journal of Supreme Court History (2009) 34#2 pp: 170-182.

- Martin, Edward Winslow (1873). - "A Complete and Graphic Account of the Crédit Mobilier Investigation". - Behind the Scenes in Washington. - (c/o Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum).

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Final Restoration of Home Rule at the South in 1877: 1872-1877. Vol. 7 (1916) online, pp 1-19, for a narrative history

External links

-

"Crédit Mobilier of America". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Crédit Mobilier of America". New International Encyclopedia. 1905. -

Johnson, Rossiter (1879). "Crédit Mobilier". The American Cyclopædia.

Johnson, Rossiter (1879). "Crédit Mobilier". The American Cyclopædia.

-

"Crédit Mobilier of America". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Crédit Mobilier of America". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.