History of Colorado Springs, Colorado

| History of Colorado Springs, Colorado | |

| The 1903-1973 El Paso County Courthouse (now the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum).[1] | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| State | Colorado |

| County | El Paso |

| Municipality | City of Colorado Springs[2] |

| 1st settlement | 1859 Colorado City [3] |

| Oldest building |

1859 "Dr. Gavin's Cabin", in Old Colorado City's Bancroft Park since 1927[4] |

| Population history |

|

Before it was founded, the site of modern-day Colorado Springs, Colorado, was part of the American frontier. Old Colorado City, built in 1858 during the Pike's Peak Gold Rush was the Colorado Territory capital. The town of Colorado Springs, was founded by General William Jackson Palmer as a resort town. Old Colorado City was annexed into Colorado Springs. Railroads brought tourists and visitors to the area from other parts of the United States and abroad. The city was noted for junctions for seven railways: Denver and Rio Grande (1870), Denver and New Orleans Manitou Branch (1882),[14] Colorado Midland (1886-1918), Colorado Springs and Interurban (1887-1932 horse/electric tram), Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe (1889), Rock Island (1889), and Colorado Springs and Cripple Creek (1900-22 Short Line) Railways. It was also known for mining exchanges and brokers for the Cripple Creek Gold Rush.[11]

Palmer, Spencer Penrose, and Winfield Scott Stratton provided land and funding for parks, buildings, and non-profit organizations. It was a home to successful mine owners, artists, and writers. The climate and mountain setting made it a popular tourist destination and health resort. A dry climate supported resorts for people with weak lungs or tuberculosis,[11] including the 19th and 20th century Colorado Springs sanatoria.

In 1928-29, Alexander Aircraft Company was "the largest aircraft manufacturer in the world."[15] The city supported three World War II and Cold War military installations. The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) center was located within the city before relocating to Cheyenne Mountain.

Geological history

Notable landforms, such as the Cheyenne Mountain on the city's southwest, were formed of Precambrian Pikes Peak granite uplifted in the Ancestral Rocky Mountains.[16] Formation of the city's hills—including the Mesa, Institute Heights, and Knob Hill—created valleys for the Camp, Cheyenne, and Fountain creeks which enter the city on the west; Monument Creek from the north; and Cottonwood & Sand creeks (east). Bluffs formed with American Lower Eocene coal deposits[17] of the Colorado Springs lignite field. Eponymic mineral springs, which flowed in 1912 from aquifers under the elevated landforms, included Horn's Mineral Springs at 1210 Lincoln,[1] Monument Springs[18] on Monument Creek's west bank in Monument Valley Park,[19] and Jimmy Springs at the camp. There were also other springs located at that time on Bijou, Kiowa, 7th, and Cucharra streets and West Cheyenne Road.[19]

Before founding

Native American settlements

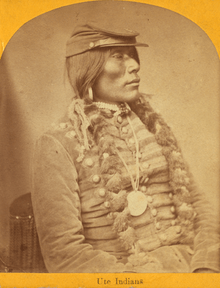

Ute people have believed that the Pikes Peak region is their home. Their name for Pikes Peak is Tavakiev, meaning sun mountain. They lived a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Summers were spent in the mountains, which was considered by other tribes to be the domain of the Utes. In the fall they would travel down Ute Pass[lower-alpha 1] and visited the springs where they "made offerings to the spirits of the springs for good health and good hunting". From there they began a journey eastward to hunt buffalo. They spent winters in mountain valleys where they were protected from the weather. Garden of the Gods artifacts from up to 3,500 years ago, such as grinding stones, "suggest the groups would gather together after their hunt to complete the tanning of hides and processing of meat."[21][22] For instance, grinding stones found there from c. 1330 B.C. were used by the Ute people.[20]

Arapaho, Cheyenne, and other tribes also gathered in the Manitou Springs and Garden of the Gods areas.[23] Cheyenne Mountain, named after the Cheyenne people was considered a great source of timber for teepee poles. Waterfalls were believed by the Cheyenne and Arapaho to be a spiritual place where one might gain inspiration, which may have been why they visited the local Cañons.[22]

By 1882, Utes were forced to live on reservations in southwestern Colorado and eastern Utah.[21]

Treaties and settler exploration

Part of the American frontier, Colorado Springs land was in New France (1682 treaty), New Spain (1762 treaty), and the United States' Louisiana Purchase beginning in 1803.[24] When the region was bought by the United States with the Louisiana Purchase, explorers entered the area. Zebulon Pike explored the region in November 1806.[23] The land including the current city was designated part of the 1854 Kansas Territory and on June 24, 1857, a team of Major John Sedgwick's Column camped at the mouth of Jimmy Camp Creek.[24][lower-alpha 2] In 1858, a subsequent April US Army camp was near Soda Spring in Manitou Springs,[26] and the Lawrence Party camped at Garden of the Gods in July before establishing a town in or after September of that year at Montana City, which is now part of Denver, Colorado.[27]

Foundation

Gold rush settlement

Colorado City, now called Old Colorado City, was founded at the confluence of Fountain and Camp creeks on August 13, 1859, making it the first Pikes Peak region settlement.[23][28] The Colorado City area became part of the Jefferson Territory on October 24 and of El Paso County on November 28, 1859. From November 5, 1861, until August 14, 1862 (including one legislative session), the city was the Colorado Territory capital until moved to Denver.[29]

Roads into the area included a toll road that connected to the northeast with the Overland's 1865 "Despatch Express Route".[30] Southward out of Colorado City a stage road (now Old Stage Road) traversed through South Cheyenne Creek's canyon to Cripple Creek,[31] and a carriage road through North and South Cheyenne Canyons[32] and westward was the Ute Pass Wagon Road.[30] Another route into the area was the north-south Cherokee Trail / Jimmy Camp Trail,[33] which was near the Goodnight–Loving Trail.[30]

Colorado Springs founding and incorporation

Civil War General William Jackson Palmer came to the Colorado Territory as a surveyor with the Kansas Pacific Railway in search of possible railroad routes.[34] Dr. William Abraham Bell from England was also part of the survey party.[35] Having viewed the valley in the shadow of Pikes Peak as an ideal town site in July 1869,[36] Palmer and Bell founded Fountain Colony, downstream of Colorado City, on July 31, 1871, and it was laid out by the Colorado Springs Company that year.[35][36][lower-alpha 3] The town was named Colorado Springs by 1879.[13] It was named for three natural mineral springs near Monument Creek[39][lower-alpha 4] or the springs in nearby Manitou Springs.[40]

The El Paso County seat transferred from Colorado City in 1873 to the Town of Colorado Springs.[41] Early infrastructure included 60 mi (97 km) of irrigation canals along streets and a drinking water supply from Manitou's Ruxton Creek by 1879.[13] Water was diverted to the Ruxton Creek Basin from the Middle Beaver Creek basin in 1889.[42]

The town was "Little London" for the many English tourists and settlers actively recruited by Palmer's English associate Dr. William Abraham Bell and Palmer's English financial backers who provided the capital for his railroad,[34][43] Denver and Rio Grande Railroad served the city beginning October 1871.[44] In 1873 Colorado Springs became the county seat for the county; Previously, Old Colorado City was the county seat.[45]

.jpg)

The Pikes Peak region was one of the most popular travel destinations in the late 19th century United States.[46] The town saw an influx of writers, artists and people from England in the late 1870s, some of whom made their home in the town.[45] Some of the key attractions were Garden of the Gods, Glen Eyrie, Pikes Peak, and Cheyenne Canyon.[40][47][lower-alpha 5]

Domestic and international travelers were drawn to the high altitude, sunshine, mineral waters, and dry climate. The town was described as "a veritable Eden for consumptive invalids".[40][47] At the peak of its period as a health resort for tuberculosis treatment in Colorado Springs, there were 17 tuberculosis hospitals in the area. The permanent residents fear of catching the highly contagious disease nearly resulted in a state bill that would have required tubercular patients to wear bells to announce their presence.[49]

The Colorado School for the Deaf and Blind and Colorado College were founded in 1874.[50] Palmer opened the Antlers Hotel in 1882.[45] Colorado Springs incorporated on June 19, 1886,[51]

After settlement

Late 19th century and early 20th century

- Boulder Crescent Place Historic District

- El Pomar Estate

- Glen Eyrie

- Monument Valley Park

- North End Historic District

- North Weber Street-Wahsatch Avenue

- Old Colorado City

- Rock Ledge Ranch

Colorado Midland Railroad began service in the town in 1885. Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad service began in 1889. Trolleys ran to Manitou Springs the following year.[50] Colorado Springs grew by 164% when 11,140 people settled in the town between 1880 and 1890.[52]

After the Cripple Creek gold discovery in 1891, the people who made a fortune from the gold rush and industry built large houses on Wood Avenue, then in the undeveloped downtown area of Colorado Springs. Several large stone buildings like Colorado College, St. Mary's Church, the first Antlers Hotel, the library, and the county courthouse were built on wide streets, in anticipation of significant population growth.[52][53][54] By 1898, the city that had grown through annexations[55] of Old Colorado City, Ivywild, Roswell and other towns[56] was designated into quadrants by the north-south Cascade Avenue and the east-west Washington/Pike's Peak avenues, along with voting precincts 27-41 and five wards with the fire alarm zones.[57]:10

The Tesla Experimental Station operated beginning in 1899 on Knob Hill, near the current intersection of Foote and Kiowa Streets.[58] Governor James Hamilton Peabody sent troops to Colorado City in 1903 to settle a miner's strike. They set up Camp Peabody at what became the 1903 Colorado Labor War.[59][lower-alpha 6] By 1905, the lake at Monument Valley Park was built at a cost of US$750,000 (equivalent to $19,786,000 in 2015), the YMCA building was built for $100,000 (equivalent to $2,638,000 in 2015), and Broadmoor Country Club built one of the city's two polo fields.[61]

There was a plan in 1911 plan to build a Colorado Springs Union Depot to consolidate the two railroad passenger depots, but it was never completed.[62] A zoological park was built along Cheyenne Creek, near Bear Creek Road (now Eighth Street), by 1916[63] and the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo was built in 1925 above The Broadmoor resort on the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo Road.[64][65] In 1919, William Kennon Jewett deeded the Colorado Springs Golf Club's golf course to the City of Colorado Springs.[66] Aircraft flights to the Broadmoor neighborhood fields began in 1919,[67] the Alexander Airport (later called Nichols Field) north of the city opened in 1925 and land was purchased in 1927 for the first Colorado Springs Municipal Airport.[67]

Successful mine owner Winfield Scott Stratton funded the Myron Stratton Home for housing itinerant children and the elderly, donated land for City Hall, the main post office, the Courthouse, and a park; he also greatly expanded the city's trolley car system and built the Mining Exchange building.[68][69][70] Spencer Penrose and his wife, over the course of their lives, financed construction of The Broadmoor resort (1918), Pikes Peak Highway, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo (1921), Will Rogers Shrine of the Sun (1937), made a significant donation to what is now known as Penrose-St Francis Health Services, and established the El Pomar Foundation, which still oversees many of his contributions in Colorado Springs today.[50][71][72][73] A bronze sculpture of Palmer on a horse was unveiled in 1929.[50] To many residents who lived in Colorado Springs in the years since, Palmer became known as "the man on the iron horse".[74]

Many of the large homes in Colorado Springs were made into apartment houses or became boarding houses during the Depression of the 1930s and when there was a housing shortage during World War II. Some homes were also converted into office space.[52]

Land purchases and annexation

City-owned properties that are, or were originally, outside of the city limits include:

- Colorado Springs Airport (annexed 1964)[75]

- North Cheyenne Cañon Park

- Evergreen Cemetery (1.5 mi SE in 1898)

- Manitou Hydroelectric Plant (bought 1905)[76]

- Pikes Peak Highway

- Pikes Peak Meadows (annexed c. 1985)

- Original Colorado Springs Municipal Airport

- Tesla Hydroelectric Plant (at USAFA); torn down in 1964[77]

Colorado Springs annexed Roswell in 1880.[55] The city purchased 640 acres in North Cheyenne Cañon after citizens of Colorado Springs voted for the measure in 1885.[22]

Between 1889 and 1890 Seavey's Addition, West Colorado Springs, East End, and another North End addition were annexed to the city.[75] In 1891, the Broadmoor Land Company began developing the Broadmoor suburb and built the Broadmoor Casino. By December 12, 1895, the city had "four Mining Exchanges and 275 mining brokers."[78] Silver Cascade Falls, Helen Hunt Falls, N. Cheyenne Canyon Road and other land in North Cheyenne were purchased and donated to the city in 1907 by William Jackson Palmer. The cañon was considered by the Park Commission to be "by far the grandest and most popular of all the beautiful cañons near the city."[22] Several areas near downtown, such as North End and Wood Avenue were annexed by 1912[55] and Colorado City (now called Old Colorado City) was annexed in 1917.[50] After a lull between 1917 and 1946, annexation began in earnest. Some examples of annexed areas are: Pleasant Valley (1950), Knob Hill (1952), Austin Bluffs (1958-1965), Pike View (1962), Papeton (1968), Woodmen Valley (1969), and Stratton Additions (1966-1971).[55]

Between 1960 and 1970 divisions of Cheyenne Mountain, Elmere, Black Forest-Peyton, Fountain, Pikes Peak and Monument were annexed into Colorado Springs, resulting in an increased population of 37,500 by 1970.[79] Broadmoor and Skyway were annexed, without a vote of its residents, before the state's Poundstone Amendment (1974) was enacted.[80] Briargate was annexed in 1982.[81]

Parks

The first city park in Colorado Springs, included in the initial town plans in 1871, is Acacia Park. It was initially called Acacia Square or North Park. General William Jackson Palmer donated land to establish Acacia and additional parks, including: Antlers Park, Monument Valley Park, North Cheyenne Cañon, Palmer Park, Pioneer Square (South) Park, Prospect Lake and Bear Creek Cañon Park. He donated a total of 1,270 acres of land, some of which was also used for scenic drives, tree-lined roadways and foot and bridle paths. The Perkins heirs donated Garden of the Gods to the city in 1909.[82]

Military installations

Military units/operations were also posted in other buildings within the city limits:

- 1942: ATSF Depot

- 1942: Alamo Garage (20th Combat Mapping Sq)

- 1942: City Auditorium

- 1942: Kaufman Building

- 1963: Chidlaw Building

- 1985: Temporary Military Facility

- 1990: Federal Building

- 1999: Atrium II (GPS Support Center)

- 2002: Atrium II (Space Analysis Center)

- 2003: Space Operations School

The city purchased land at the southern border of the city and donated it to the War Department. After the Pearl Harbor attack, the U.S. Army established Camp Carson, named for General Kit Carson, near the southern borders of the city as a training facility in preparation for World War II.[83] Colorado Springs Municipal Airport was used by the Colorado Springs Army Air Base and was assigned to the Air Force in 1942 for photo reconnaissance training. It was renamed Peterson Field for Lt. Edward J. Peterson who died during a takeoff from the field.[84]

After World War II there was little military presence in the city. Camp Carson had only 600 soldiers. When the Korean War began there was an influx of military personnel.[83] Over time, Camp Carson grew and became a significant industry within the city.[85] In 1951, the United States Air Defense Command moved to Colorado Springs and opened Ent Air Force Base.[84]

In 1954 Camp Carson became Fort Carson.[83] That year the United States Air Force Academy was established.[50]

NORAD's main facility was built in Cheyenne Mountain, which permanently secured the city's military presence and as a result increased the city's revenue, and opened in 1966.[86] Ent Air Force Base was shut down and in 1977 was converted into the United States Olympic Training Center.[87] Peterson Field was renamed Peterson Air Force Base and was permanently activated.[84]

In 1983 Falcon Air Force Base, (later Schriever Air Force Base), was founded as a missile defense and satellite control center.[88] Air Force Space Command is located on Peterson AFB.[84]

Late 20th and early 21st century

Between 1965 and 1968 the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, Pikes Peak Community College and the Colorado Technical University were established in the city.[50]

In 1972, the city's first National Register of Historic Places designation was the 1903 El Paso County Courthouse. The first designated historic district was the 1979 Rock Ledge Ranch Historic Site. In 1977, most of the former Ent Air Force Base became the first US Olympic Training Center, and the US Olympic Committee moved there in 1978.

In 2012, the Waldo Canyon fire destroyed 346 homes and killed two people in the city.

Gallery

- Commercial and public buildings

- Alamo Hotel, 128 S. Tejon Street

- Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Passenger Depot, 555 E. Pikes Peak Avenue

- Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, 30 W. Dale Street

- Midland Terminal Railroad Roundhouse, 600 S. 21st Street

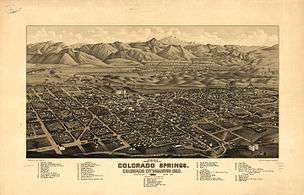

1882 Bird's Eye View of Colorado Springs and Manitou Springs, Colorado

1882 Bird's Eye View of Colorado Springs and Manitou Springs, Colorado

Notes

- ↑ The Ute Pass Trail was the "old Indian trail...ran across the hills just south of the Garden of the Gods and out into the valley of Camp Creek through a gap in the ridge at what was afterwards known as the Chambers Ranch, then across Camp Creek and over the Mesa, crossing Monument Creek just above the present town of Roswell".[20]

- ↑ There were also 1776, 1806, & 1820 expedition explorers—Juan Bautista de Anza, Zebulon Pike, Stephen Harriman Long— that passed south of the city limits.[25] Don Juan Bautista de Anza visited the area from New Mexico and created a map that shows Almagre, the Spanish name given to what became Pikes Pike. Meaning red earth, Almagre (AL-MA-GREY) is description of the mountains pinkish rocks.[22] During his visit in 1776, he surprised a small force of the Comanche near present day Colorado Springs and in Pueblo fought and won a battle with the Comanche.[25]

- ↑ In reaction to the saloons, prostitution, and opium dens of Colorado City, Palmer purchased the land for the new town east of the wild town and outlawed the consumption of alcohol within the new town's borders. Alcohol was sold, however, by druggists for "medicinal purposes". In 1933, at then end of the Prohibition, Colorado Springs lifted the ban of the sale and consumption of alcohol.[37][38]

- ↑ The springs that were located in what is now Monument Valley Park, were "sealed over" during a significant flood in 1935.[39]

- ↑ The waters in Colorado Springs contained so much natural fluoride that some peoples’ teeth developed Colorado Stain. In 1909, Dr. Frederick McKay of Colorado Springs discovered the Colorado Stain connection and that a little fluoride added to water would prevent cavities.[48]

- ↑ Old Colorado City was the location of a 1903 labor strike that spread to Cripple Creek and eventually led to the Colorado Labor Wars.[60]

References

- 1 2 The Giles City Directory of Colorado Springs and Manitou (PDF) (almanac). The Giles Directory Company. May 1903. Retrieved November 2, 2013. Chapters: The Giles Classified Business Directory of Colorado Springs [p. 559] ... of Colorado City [p. 715] ... of Manitou [p. 755]

- ↑

- "Colorado Springs Country Club (193344)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 17, 2013. "13-OCT-1978...385238N 1044724W"

- "Cragmor Sanitarium (193349)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 1, 2013. "13-OCT-1978...385326N 1044742W"

- ↑ "Old Colorado Springs Historical Society". Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ↑ Old Colorado City Historic Commercial District (PDF) (NRHP Inventory--Nomination Form). November 2, 1982. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ↑ Thomas E. Cronin; Robert D. Loevy (October 15, 2012). Colorado Politics and Policy: Governing a Purple State. U of Nebraska Press. p. 302. ISBN 0-8032-4489-4.

- ↑ "Colorado Springs (city) Quick Facts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ↑ Census of population and housing (2000): Colorado Population and Housing Unit Counts. DIANE Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4289-8557-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Colorado Springs Population Growth, 1960-2000. CensusScope. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ↑ United States. Bureau of the Census. Census of Population: 1950: Number of inhabitants. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 6–18.

- 1 2 George G. Anderson (1916). Report on the Colorado Springs water system: its resources and needs. The Water Department. p. 6.

- 1 2 3 "Colorado's Mining Craze.". New York Times. December 2, 1895. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

"...a city of less than 20,000 people

- 1 2 "North (Downtown) Walking Tour" (PDF). City of Colorado Springs. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Colorado Springs, Manitou and Colorado City Directory (PDF) (almanac), W. H. H. Raper & Co., May 1879, retrieved December 10, 2013,

El Paso county...now stands at the head of the wool producing counties of the State.

- ↑ Colorado. Railroad Commissioner (1886). First Annual Report of the Railroad Commissioner of the State of Colorado for the Year Ending June 30, 1885. Collier & Cleaveland lith. Company, state printers. p. 289.

- ↑ Freeman, Paul (October 13, 2013). "Colorado Springs area". Airfields-Freeman.com. Retrieved November 17, 2013. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Wilson, Anna Burack; Sims, P.K. (2002). The Colorado Mineral Belt Revisited: An Analysis of New Data (PDF) (Report). Open-File Report 03-046. USGS. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

in central Colorado where the mineral belt abruptly widens from a width of about 15 to 60 km to about 140 km.

- ↑ Annual Report of the United States Geological and Geographical. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

Fort Union or Great Lignite group

- ↑ Tourists guide to Colorado Springs, Manitou, Colorado City and the Pike's Peak Region (Map). "Geo. S. Clason, Denver, Colo.". 1906. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- 1 2 Charles Mulford Robinson (January 1, 2012). A City Beautiful Dream: The 1912 Vision for Colorado Springs. Pikes Peak Library District. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-56735-288-7.

- 1 2 Howbert, Irving (1970) [1925/1914]. Memories of a Lifetime in the Pike's Peak Region (PDF). The Rio Grande Press (transcript of first edition at DaveHughesLegacy.net). ISBN 0-87380-044-3. LCCN 73115107. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- 1 2 "Ute Indians of Colorado". Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The First People of the Cañon and the Pikes Peak Region". City of Colorado Springs. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Colorado Springs History and Heritage". Visit Colorado Springs. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- 1 2 William Y. Chalfant (October 1, 2002). Cheyennes and Horse Soldiers: The 1857 Expedition and the Battle of Solomon's Fork. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8061-3500-7.

- 1 2 Thomas, Alfred Barnaby (ed.) (1932) "Governor Anza's Expedition against the Comanche 1779" Forgotten Frontiers: A Study of the Spanish Indian Policy of Don Juan Bautista de Anza, Governor of New Mexico, 1777–1787 University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, pp. 66–71 OCLC 68116825

- ↑ Marcy, Brig.Gen. R. B. (April 1, 1889). "Big Game Hunting in the Wild West: The American Elk or Wapiti". Outing. XIV (1): 31–9.

I passed the month of April, 1858, in camp near the Manitou Springs in Colorado (then called [sic] “Soda Spring” [which was 1 of the mineral springs])... I was awakened one morning about daylight by my orderly telling me that there was a herd of elk across the [creek] “Fontaine qui boulle,” upon a bluff only about 200 yards from our camp.

(transcript available from the LA84 Foundation) - ↑ Frank Hall; Rocky Mountain Historical Company (1895). History of the state of Colorado, embracing accounts of the pre-historic races and their remains: the earliest Spanish, French and American explorations ... the first American settlements founded; the original discoveries of gold in the Rocky Mountains; the development of cities and towns, with the various phases of industrial and political transition, from 1858 to 1890 ... The Blakely Printing Company. p. 20.

- ↑ "El Paso County". History Colorado. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ↑ Jerome C. Smiley (1913). Semi-Centennial History of Colorado. Chicago: Lewis. pp. 367–369.

- 1 2 3 Historic Trail Map...Central Colorado (PDF) (Map). Geologic Investigations Series I-2639 (Sheet 1 of 2). Cartography by Scott, Glenn R. USGS. 1999.

- ↑ Randy Jacobs; Robert Ormes (March 1, 2000). Guide to the Colorado Mountains. The Mountaineers Books. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-9671466-0-7.

- ↑ Chicago, Rock Island; Pacific Railway Company (1898). Manitou and the Mountains. Chicago: Poole Brothers. pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Stanley Buchholz Kimball (January 1, 1988). Historic Sites and Markers Along the Mormon and Other Great Western Trails. University of Illinois Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-252-01456-7.

- 1 2 "Taming a Wilderness Part 1". Ghostdepot.com. January 3, 1926. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- 1 2 Harrison, Deborah. Maitou Springs. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- 1 2 Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Jan MacKell (2007). Brothels, Bordellos, and Bad Girls: Prostitution in Colorado, 1860-1930. UNM Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8263-3343-8.

- ↑ Inner Source Designs; Kathy and Lee Hayward (November 1, 2009). Drinking and Driving in Colorado: A Guide to Colorado's Brewpubs. Inner Source Designs. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-9822571-1-1.

- 1 2 Brandon Fibbs (July 25, 2003). "Fun with the Founder - Move over, Columbus: Colorado Springs founder gets back his holiday". The Gazette (accessed via HighBeam Research). Colorado Springs, CO.

- 1 2 3 Appleton's Illustrated Hand-book of American Winter Resorts for Tourists and Invalids. D. Appleton. 1877. pp. 75–76. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Capace, Nancy (March 1, 1999). Encyclopedia of Colorado (Google books). North American Book Dist LLC. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-403-09813-2. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Swab, Eric (August 2011). "Colorado Springs South Slope Water" (PDF). Friends of the Peak Newsletter: 6–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2014. (see also http://www2.coloradocollege.edu/dept/ev/faculty/hecox/Courses/EV421/March-April%202011/2010%20PPWS%20Forest%20Management%20Plan.pdf )

- ↑ Darcy Mazel. "Bristol Elementary School Historical Wall of Colorado Springs". Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ↑ Marshall Sprague (1984). Colorado, a History. W W NORTON & Company. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-393-30138-0. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Nancy Capace (March 1, 1999). Encyclopedia of Colorado. North American Book Dist LLC. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-403-09813-2. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Allan C. Lewis (May 24, 2006). Railroads of the Pikes Peak Region, 1900-1930, CO. Arcadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7385-3125-0. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- 1 2 Duane A Smith (2008). Rocky Mountain Heartland: Colorado, Montana, and Wyoming in the Twentieth Century. University of Arizona Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8165-2759-5. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ John J. Murray; June H Nunn; James G Steele (June 5, 2003). The Prevention of Oral Disease. Oxford University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-19-263279-1.

- ↑ Stephanie Waters (2012). Ghosts of Colorado Springs and Pikes Peak. The History Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-60949-467-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Paul T. Hellmann (November 1, 2004). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Taylor & Francis. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-203-99700-0. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "List of Incorporated Cities and Towns" (PDF). State of Colorado. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "North (Downtown) Walking Tour" (PDF). City of Colorado Springs. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ↑ Colorado College Tutt Library. Colorado Springs Views Looking West on Pikes Peak Avenue. Inventory of the Colorado Springs Area: Early Views. Glass Plate Negatives C1-C12. Retrieved on: July 12, 2011.

- ↑ Loevy, R. (August 1, 2010). The Complete History of the Old North End Neighborhood in Colorado Springs, Colorado, pp. 1–2. Colorado College. Retrieved on: July 12, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Annexation Data". City of Colorado Springs. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Stephanie Waters (2012). Ghosts of Colorado Springs and Pikes Peak. The History Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-60949-467-4.

- ↑ Directory of Colorado Springs (PDF) (almanac), The Out West Printing and Stationery Co., 1898, retrieved November 5, 2013

- ↑ W. Bernard Carlson (May 7, 2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton University Press. pp. 265–267. ISBN 1-4008-4655-2.

- ↑ United Mine Workers of America (1907). Proceedings of the ... Annual Convention of the United Mine Workers of America. United Mine Workers of America. p. 277.

- ↑ Colorado's War on Militant Unionism, James H. Peabody and the Western Federation of Miners, George G. Suggs, Jr., 1972, page 47

- ↑ Henry Russell Wray (March 1905). "Colorado Springs". The National Magazine. XXI October 1904–March 1905: 692–695. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ↑ Report of the Commission on the Colorado Springs Union Depot (available at PPLD Special Collections and the Colorado College Tutt Library)

- ↑ Colorado Springs, Colorado City and Manitou City Directory. Vol. XIII. The R. L. Polk Directory Co. 1916.

- ↑ Guide to Colorado Historic Places: Sites Supported by the Colorado Historical Society's State Historical Fund. Big Earth Publishing. February 28, 2007. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-56579-493-1.

- ↑ Jay Warburton (December 1, 2000). The Big Fifty. iUniverse. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-595-15648-1.

- ↑ "William Kennon Jewett". Colorado Golf Association. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- 1 2 Hartman, James Edward (June 28, 1996). Original Colorado Springs Municipal Airport (NRHP Inventory--Nomination Form).

- ↑ Walking Into Colorado's Past: 50 Front Range History Hikes. Big Earth Publishing. October 30, 2006. pp. 190, 188–190. ISBN 978-1-56579-519-8. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Allan C. Lewis (May 24, 2006). Railroads of the Pikes Peak Region, 1900-1930, CO. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 91–92, 94–95, 102. ISBN 978-0-7385-3125-0. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Elizabeth Jameson (1998). All that Glitters: Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek. University of Illinois Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-252-06690-0. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Nancy Capace (March 1, 1999). Encyclopedia of Colorado. North American Book Dist LLC. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-403-09813-2. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Richard Wood (November 30, 2005). Here Lies Colorado : Fascinating Figures in Colorado History. Farcountry Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-1-56037-334-6. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Duval; Banks; Laurence Parent (June 14, 2011). Insiders' Guideо to Colorado Springs. Globe Pequot Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7627-6936-0. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Rhonda Davis Wilcox. The Man on the Iron Horse.

- 1 2 annexdata.xls (spreadsheet), SpringsGov.com, retrieved October 27, 2013

- ↑ "Manitou Hydroelectric Plant" (Wikimapia image and article). Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Historic Antler Hotel - Colorado Springs". WesternMiningHistory.com. August 12, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Colorado's Mining Craze.". New York Times. December 2, 1895. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

...a city of less than 20,000 people... Colorado Springs is a resort for consumptives or persons having weak lungs.

- ↑ United States. Bureau of the Census (1972). 1970 Census of Population: United States, Alabama-Mississippi. U.S. Bureau of the Census. p. SA7–PA21. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Thomas E.. Cronin; Robert D.. Loevy (1993). Colorado Politics & Government: Governing the Centennial State. U of Nebraska Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-8032-1451-4. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Urban Land. Urban Land Institute. 1985. p. 3. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Parks, Trails and Open Spaces". City of Colorado Springs. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Fort Carson Garrison History". U.S. Army Garrison, Fort Carson, Colorado. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Peterson Air Force Base Facts Sheet". Peterson Air Force Base. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Fort Carson, Colorado". Cdphe.state.co.us. October 29, 1995. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ↑ Pam Zubeck (May 9, 2008). "NORAD marks 50 years with wary eye on the sky". The Gazette. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ↑ "USOC - Colorado Springs History". The Sports Corp. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Facts Sheet". Schriever Air Force Base. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

External links

|

| |

|

|

![]() Media related to History of Colorado Springs at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Colorado Springs at Wikimedia Commons