Cursive Hebrew

Cursive Hebrew (Hebrew: כתב עברי רהוט ktav ivri rahut) is a collective designation for several styles of handwriting the Hebrew alphabet. Modern Hebrew, especially in informal use in Israel, is handwritten with the Ashkenazi cursive script that had developed in Central Europe by the 13th century.[1] This is also a mainstay of handwritten Yiddish.[2] It was preceded by a Sephardi cursive script, known as Solitreo that is still used for Ladino[3] and by Jewish communities in Africa.

Contemporary forms

As with all handwriting, cursive Hebrew displays considerable individual variation. The forms in the table below are representative of those in present-day use.[4] The names appearing with the individual letters are taken from the Unicode standard and may differ from their designations in the various languages using them – see Hebrew alphabet / Pronunciation of letter names for variation in letter names. (Table is organized right-to-left reflecting Hebrew's lexicographic mode.)

| Alef א | Bet ב | Gimel ג | Dalet ד | He ה | Vav ו | Zayin ז | Het ח | Tet ט | Yod י | Kaf כ / ך |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamed ל | Mem מ / ם | Nun נ / ן | Samekh ס | Ayin ע | Pe פ / ף | Tsadi צ / ץ | Qof ק | Resh ר | Shin ש | Tav ת |

Note: Final forms are to the left of the initial/medial forms.

Historical forms

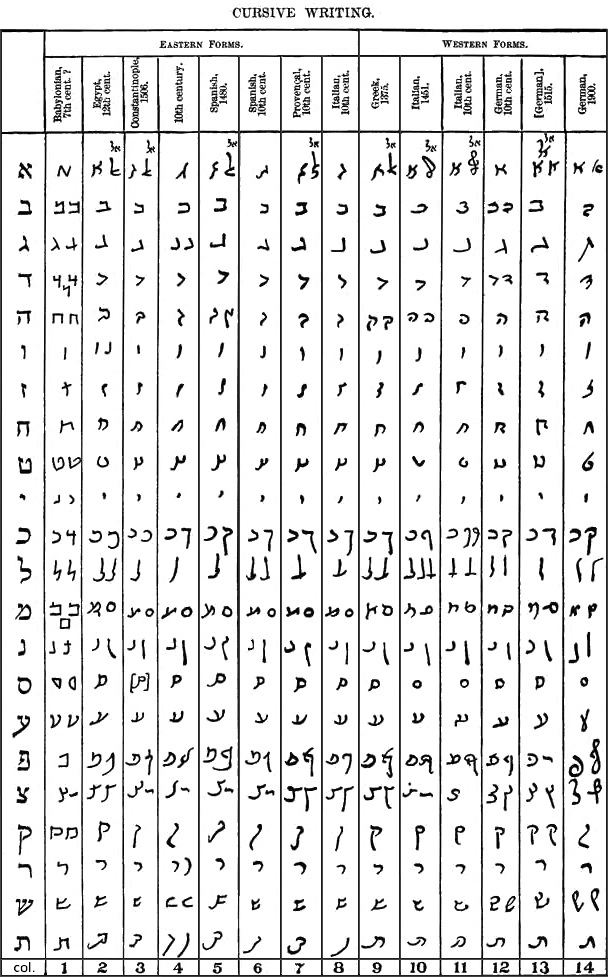

This table shows the development of cursive Hebrew from the 7th through the 19th centuries. This is discussed in the following section, which makes reference to the columns in the table, numbered 1 through 14.

Figure 3: "Cursive Writing" (Jewish Encyclopedia, 1901-1906).

Column:

- Incantation upon Babylonian dish[5]

- Egyptian, 12th century.

- Constantinople, 1506.

- 10th century.

- Spanish, dated 1480.

- Spanish, 10th century.

- Provençal, 10th century.

- Italian, 10th century.

- Greek, dated 1375.

- Italian, dated 1451.

- Italian, 10th century.

- German, 10th century.

- Eleazer of Worms, copied at Rome in 1515 by Elias Levita[6]

- Ashkenazi, 19th century.

History

The brief inscriptions daubed in red ink upon the walls of the catacombs of Venosa are probably the oldest examples of cursive script. Still longer texts in a cursive alphabet are furnished by the clay bowls found in Babylonia and bearing exorcisms against magical influences and evil spirits. These bowls date from the 7th or 8th century, and some of the letters are written in a form that is very antiquated (Figure 3, column 1). Somewhat less of a cursive nature is the manuscript, which dates from the 8th century.[7] Columns 2–14 exhibit cursive scripts of various countries and centuries. The differences visible in the square alphabets are much more apparent. For instance, the Sephardi rounds off still more, and, as in Arabic, there is a tendency to run the lower lines to the left, whereas the Ashkenazi script appears cramped and disjointed. Instead of the little ornaments at the upper ends of the stems, in the letters ![]() a more or less weak flourish of the line appears. For the rest the cursive of the Codices remains fairly true to the square text.

a more or less weak flourish of the line appears. For the rest the cursive of the Codices remains fairly true to the square text.

Documents of a private nature were certainly written in a much more running hand, as the sample from one of the oldest Arabic letters written with Hebrew letters (possibly the 10th century) clearly shows in the papyrus, in "Führer durch die Ausstellung", Table XIX., Vienna, 1894, (compare Figure 3, column 4). However, since the preservation of such letters were not held to be of importance, material of this nature from the earlier times is very scarce, and as a consequence the development of the script is very hard to follow. The last two columns of Figure 3 exhibit the Ashkenazi cursive script of a later date. The next to the last is taken from a manuscript of Elias Levita. The accompanying specimen presents Sephardi script. In this flowing cursive alphabet the ligatures appear more often. They occur especially in letters which have a sharp turn to the left (ג, ז, כ, נ, צ, ח), and above all in נ, whose great open bow offers ample space for another letter (see Figure 2).

The following are the successive stages in the development of each letter:

- Alef is separated into two parts, the first being written as

, and the perpendicular stroke placed at the left

, and the perpendicular stroke placed at the left  . By the turn of the 20th century, Ashkenazi cursive had these two elements separated, thus ׀c, and the acute angle was rounded. It received also an abbreviated form connected with the favorite old ligature

. By the turn of the 20th century, Ashkenazi cursive had these two elements separated, thus ׀c, and the acute angle was rounded. It received also an abbreviated form connected with the favorite old ligature  , and it is to this ligature of Alef and Lamed that the contracted Oriental Aleph owes its origin (Figure 3, column 7).

, and it is to this ligature of Alef and Lamed that the contracted Oriental Aleph owes its origin (Figure 3, column 7). - In writing Bet, the lower part necessitated an interruption, and to overcome this obstacle it was made

, and, with the total omission of the whole lower line,

, and, with the total omission of the whole lower line,  .

. - In Gimel, the left-hand stroke is lengthened more and more.

- Dalet had its stroke put on obliquely to distinguish it from Resh; however, since in rapid writing it easily assumed a form similar in appearance to ר, ד in analogy with ב was later changed to

.

. - A transformation very similar to this took place in the cases of final Kaf and of Qof (see columns 2, 5, 11, 14), except that Kaf opened out a trifle more than Qof.

- The lower part of Zayin was bent sharply to the right and received a little hook at the bottom.

- The left-hand stroke of Ṭet was lengthened.

- Lamed gradually lost its semicircle until (as in both Nabataean and Syriac) by the turn of the 20th century, it became a simple stroke, which was bent sharply toward the right. In the modern script today the Lamed has regained its semicircle.

- Final Mem branches out at the bottom, and in its latest stage is drawn out either to the left or straight down.

- In Samekh the same development also took place, but it afterward became again a simple circle.

- To write 'Ayin without removing the pen from the surface, its two strokes were joined with a curl.

- The two forms of the letter Pe spread out in a marked flourish.

- For Tsadi the right-hand head is made longer, at first only to a small degree, but later on to a considerable extent.

- In the beginning Shin develops similarly to the same letter in Nabataean, but afterward the central stroke is lengthened upward, like the right arm of Tsadi, and finally it is joined with the left stroke, and the first stroke is left off altogether.

- The letters ה, ד, ח, ן, נ, ר, ת, have undergone little modification: they have been rounded out and simplified by the omission of the heads.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ada Yardeni, The Book of Hebrew Script: History, Palaeography, Script Styles, Calligraphy & Design, The British Library, 2002, ISBN 1-58456-087-8, p. 97

- ↑ Sheva Zucker, Yiddish: an Introduction to the Language, Literature, and Culture, New York City, Vols. 1 & 2, 1994 & 2002, ISBN 1-877909-66-1, ISBN 1-877909-75-0

- ↑ Marie-Christine Varol, Manual of Judeo-Spanish: Language and Culture, University of Maryland Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-934309-19-3, p. 28

- ↑ Jonathan Orr-Stav, Learn to Write the Hebrew Script: Aleph through the Looking Glass, Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-300-10841-9

- ↑ In Corpus Inscriptionum Hebraicarum 18.

- ↑ German-Ashkenazi, British Museum, Additional Manuser. of 27199 (Paleographical Society, Oriental series lxxix.).

- ↑ Hebrew Papyri: Steinschneider, Hebräische Papyrusfragmente aus dem Fayyum, in Aegyptische Zeitschrift, xvii. 93 et seq., and table vii.; C. I. H. cols. 120 et seq.; Erman and Krebs, Aus den Papyrus der Königlichen Museen, p. 290, Berlin, 1899. For the Hebrew papyri in The Collection of Erzherzog Rainer, see D. H. Müller and D. Kaufmann, in Mitteilungen aus der Sammlung der Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer, i. 38, and in Führer durch die Sammlung, etc. pp. 261 et seq.

- Cursive Hebrew in the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia