Palestinian vocalization

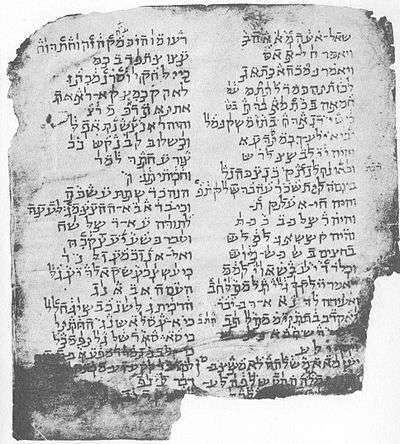

The Palestinian vocalization, Palestinian pointing, Palestinian niqqud or Eretz Israeli vocalization (Hebrew: ניקוד ארץ ישראל Niqqud Eretz Israel) is an extinct system of diacritics (niqqud) devised by the Masoretes of Jerusalem to add to the consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible to indicate vowel quality, reflecting the Hebrew of Jerusalem. The Palestinian system is no longer in use, having been supplanted by the Tiberian vocalization system.

History

The Palestinian vocalization reflects the Hebrew of Palestine of at least the 7th century CE.[1] A common view among scholars is that the Palestinian system preceded the Tiberian system, but later came under the latter's influence and became more similar to the Tiberian tradition of the ben Asher school.[2] All known examples of the Palestinian vocalization come from the Cairo Geniza, discovered at the end of the 19th century, although scholars had already known of the existence of a "Palestinian pointing" from the Mahzor Vitry.[3][4] In particular, the Palestinian piyyutim generally make up the most ancient of the texts found, the earliest of which date to the 8th or 9th centuries and predate most of the known Palestinian biblical fragments.[5]

Description

As in the Babylonian vocalization, only the most important vowels are indicated.[6] The Palestinian vocalization along with the Babylonian vocalization are known as the superlinear vocalizations because they place the vowel graphemes above the consonant letters, rather than both above and below as in the Tiberian system.[7]

Different manuscripts show significant systematic variations in vocalization.[8] There is a general progression towards a more differentiated vowel system closer to that of Tiberian Hebrew over time.[5] The earliest manuscripts use just six graphemes, reflecting a pronunciation similar to contemporary Sephardi Hebrew:[9]

| niqqud with ב | |

|

|

|

|

??? |

| Tiberian analogue |

patah, qamatz |

segol, tzere |

hiriq | holam | qubutz, shuruq |

shva |

| value | /a/ | /e/ | /i/ | /o/ | /u/ | /ə/ |

The most commonly occurring Palestinian system uses seven graphemes, reflecting later vowel differentiation in the direction of Tiberian Hebrew:[9]

| niqqud with ב | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tiberian analogue |

patah | qamatz | segol | tzere | hiriq | holam | qubutz, shuruq |

| value | /a/ | /ɔ/ | /ɛ/ | /e/ | /i/ | /o/ | /u/ |

Even so, most Palestinian manuscripts show interchanges between qamatz and patah, and between tzere and segol.[10] Shva is marked in multiple ways.[9]

Palestino-Tiberian vocalization

Some manuscripts are vocalized with the Tiberian graphemes used in a manner closer to the Palestinian system.[11] The most widely accepted term for this vocalization system is the Palestino-Tiberian vocalization.[11] This system originated in the east, most likely in Palestine.[11] It spread to central Europe by the middle of the 12th century in modified form, often used by Ashkenazi scribes due to its greater affinity with old Ashkenazi Hebrew than the Tiberian system.[12] For a period of time both were used in biblical and liturgical texts, but by the middle of the 14th century it had ceased being used in favor of the Tiberian vocalization.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Sáenz-Badillos (1993:87)

- ↑ Sáenz-Badillos (1993:90)

- ↑ Yahalom (1997:1)

- ↑ Sáenz-Badillos (1993:86)

- 1 2 Sáenz-Badillos (1993:89)

- ↑ Blau (2010:118)

- ↑ Blau (2010:7)

- ↑ Sáenz-Badillos (1993:88)

- 1 2 3 Sáenz-Badillos (1993:88–89)

- ↑ Tov (1992:44)

- 1 2 3 Sáenz-Badillos (1993:92–93)

- 1 2 Sáenz-Badillos (1993:93–94)

Bibliography

- Blau, Joshua (2010). Phonology and Morphology of Biblical Hebrew. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 1-57506-129-5.

- Sáenz-Badillos, Angel (1993). A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55634-1.

- Tov, Emanuel (1992). Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8006-3429-2.

- Yahalom, Joseph (1997). Palestinian Vocalised Piyyut Manuscripts in the Cambridge Genizah Collections. Cambridge University. ISBN 0-521-58399-3.