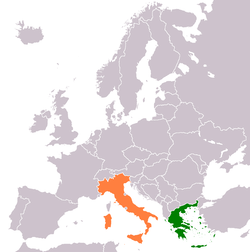

Greece–Italy relations

|

|

Greece |

Italy |

|---|---|

Greece and Italy enjoy special and strong bilateral diplomatic relations. Modern diplomatic relations between the two countries were established right after Italy's unification, and are today regarded as cordial. The two states cooperate in the fields of energy, culture and tourism, with Italy being a major trading partner of Greece, both in exports and imports.

Greece and Italy share common political views about the Balkans, the region and the world, and are leading supporters of the integration of all the Balkan states to the Euro-Atlantic family, and promoted the "Agenda 2014", which was proposed by the Greek Government in 2004 as part of the EU-Western Balkans Summit in Thessaloniki, to integrate the Western Balkan states into the European Union by the year 2014, when Greece and Italy assumed the rotating Presidency of the European Union for the first and second halves of 2014, respectively.

The two countries are EU, UN and NATO member states, and cooperate in many other multilateral organizations, such as the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the World Trade Organization, and the Union for the Mediterranean, while at same time they are promoting closer diplomatic relations and tripartite cooperation with other key Mediterranean countries, such as Israel.

History

Greece (which had gained its independence in 1832) and Italy established diplomatic relations in 1861, immediately upon Italy's unification.[1]

In early 1912, during the Italo-Turkish War, Italy occupied the predominantly Greek-inhabited Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean Sea from the Ottoman Empire. Although the 1919 Venizelos–Tittoni accord promised to cede them to Greece, Italy reneged on the promise.[2] When the Italians found that Greece had been promised land in Anatolia at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, for aid in the defeat of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, the Italian delegation withdrew from the conference for several months. Italy occupied parts of Anatolia which threatened the Greek occupation zone and the city of Smyrna. Greek troops were landed and the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22) began with Greek troops advanced into Anatolia. Turkish forces eventually defeated the Greeks and with Italian aid, recovered the lost territory, including Smyrna.[3] In 1923, the new Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini used the murder of an Italian general on the Greco-Albanian border as a pretext to bombard and temporarily occupy Corfu, the most important of the Ionian Islands.[4]

The Greek general Theodoros Pangalos, who governed Greece as a dictator in 1925–26, sought to revise the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 and launch a revanchist war against Turkey. To this end, Pangalos sought Italian diplomatic support, as Italy still had ambitions in Anatolia, but in the event, nothing came of his overtures to Mussolini.[5] After the fall of Pangalos and the restoration of relative political stability in 1926, efforts were undertaken to normalize relations with Greece's neighbours. To this end, the Greek government, especially Foreign Minister Andreas Michalakopoulos, put renewed emphasis on improving relations with Italy, leading to the signature of a trade agreement in November 1926. The Italian–Greek rapprochement had a positive impact on Greek relations with other Balkan countries, and after 1928 was continued by the new government of Eleftherios Venizelos, culminating in the treaty of friendship signed by Venizelos in Rome on 23 September 1928.[6] Mussolini favoured this treaty, as it aided in his efforts to diplomatically isolate Yugoslavia from potential Balkan allies. An offer of alliance between the two countries was rebuffed by Venizelos but during the talks Mussolini personally offered "to guarantee Greek sovereignty" on Macedonia and assured Venizelos that in case of an external attack on Thessaloniki by Yugoslavia, Italy would join Greece.[7][8]

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Mussolini sought diplomatically to create "an Italian-dominated Balkan bloc that would link Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria, and Hungary". Venizelos countered the policy with diplomatic agreements among Greek neighbours and established an "annual Balkan conference ... to study questions of common interest, particularly of an economic nature, with the ultimate aim of establishing some kind of regional union". This increased diplomatic relations and by 1934 was resistant to "all forms of territorial revisionism".[9] Venizelos adroitly maintained a principle of "open diplomacy" and was careful not to alienate traditional Greek patrons in Britain and France.[10] The Greco-Italian friendship agreement ended Greek diplomatic isolation and the beginning of a series of bilateral agreements, most notably the Greco-Turkish Friendship Convention in 1930. This process culminated in the signature of the Balkan Pact between Greece, Yugoslavia, Turkey and Romania, which was a counter to Bulgarian revisionism.[11]

Italy, an Axis power, invaded Greece in the Greco-Italian War of 1940–41, but it was only with German intervention that the Axis succeeded in controlling Greece. Italian forces were part of the Axis occupation of Greece.

Italy ceded the Dodecanese to Greece as part of the Treaty of Peace following World War II in 1947.

Today, there are still historical Greek communities in Italy and Italian communities in Greece, dating to the Middle Ages.

Diplomatic missions

Greece has an embassy in Rome, general consulates in Milan and Naples, a consulate in Venice, and honorary consulates in Trieste (General), Turin (General), Ancona, Catania, Livorno, Bari, Bologna, Brindisi, Florence, Palermo, Perugia, and a Port Consulate in Genova.

Italy has an embassy in Athens, and honorary consulates in Alexandroupoli, Kefalonia, Chania, Chios, Corfu, Corinth, Ioannina, Heraklion, Kavala, Larissa, Patra, Rhodes, Thessaloniki, Santorini, and Volos.

Bilateral relations and cooperation

_(7733619864).jpg)

Greece is one of Italy's main economic partners and they co-operate in many fields, including judicial, scientific and educational, and on the development of tourism, an important sector in both countries. There are regular high-level visits between the two countries,[12] such as the visit of the Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras to Italy in July 2014,[13][14] and there are frequent contacts between the two countries at ministerial level on various matters concerning individual sectors.

Current projects between the two countries include the Greece–Italy pipeline (which is part of the Interconnector Turkey-Greece-Italy pipeline (ITGI)), and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP).

Greece and Italy, also, along with the United States, are participating in large-scale military drills conducted by Israel, which are code-named "Blue Flag", and take place in the region of Eastern Mediterranean.[15][16]

Multilateral organizations

Both countries are full members of many international organizations, including NATO, the European Union, the Council of Europe, the OECD and the WTO. Greece and Italy were also part of the European Territorial Cooperation Programme (2007–2013), for the boost of cross-border cooperation in the Mediterranean Sea.

Cultural interaction

Greek culture in Italy The Hellenic Institute for Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Studies opened in Venice in 1951, providing for the study of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine history in Italy.

Italian culture in Greece The Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Atene in Athens is responsible for promoting Italian culture in Greece.

In July 2014, an official artistic exhibition with the title "Italy – Greece: one face, one race" was inaugurated in Rome on the occasion of the passing of the EU Council Presidency from Greece to Italy.[17][18][19][20] The title of the exhibition refers to a saying, "mia fatsa mia ratsa" (Italian: "una faccia, una razza"), often used in Greece to express the perception of close cultural affinities between Greeks and Italians.[21]

Ethnic minorities

Greeks have lived in southern Italy for centuries, and are called Griko. There are Italians in Corfu.

Agreements

- Economic Cooperation (1949)

- Avoidance of double Taxation (1964)

- Delimitation of Continental Shelf Boundaries (1977)

- Protection of the Ionian Sea Marine Environment (1979)

- Cooperation against Terrorism, Organised Crime, and Drug Trafficking (1986)

Notable Visits

- January 2006; State Visit of President of the Hellenic Republic Mr. Karolos Papoulias to Rome.

- December 2006; Visit of the Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi to Athens.

- March 2007; Official Visit of Greek Foreign Minister Dora Bakoyannis to Rome.

- August 2007; Meeting of Greek Foreign Minister with Italian counterpart Massimo D'Alema in Rome.

- September 2008; State visit of President of the Italian Republic Mr. Giorgio Napolitano to Athens.

- August 2012; Visit of the Greek Prime Minister Mr. Antonis Samaras to Rome.

- September 2012; Visit of President of the Hellenic Republic Mr. Karolos Papoulias to Italy.

- October 2013; Meeting of the Greek Prime Minister Mr. Antonis Samaras with Italian counterpart in Rome.

- July 2014; Visit of the Greek Prime Minister Mr. Antonis Samaras to Italy.

- February 2015; Meeting of Greek Prime Minister Mr. Alexis Tsipras with Italian counterpart Matteo Renzi in Rome.

Transportation

The Italian ports of Bari, Brindisi, Ancona, Venice and Trieste on the Adriatic Sea's Italian coast have daily passenger and freight ferries to the Greek ports of Corfu, Patra, Igoumenitsa and Kalamata, avoiding overland transit via the Balkan Peninsula.

See also

- Foreign relations of Greece

- Foreign relations of Italy

- Greeks in Italy

- Italians in Greece

- History of Europe

References

- ↑ "18 aprile 1861: Grecia" Documents on the establishment of diplomatic relationships with Italy

- ↑ Verzijl 1970, p. 396.

- ↑ Plowman 2013, pp. 910.

- ↑ Bell 1997, p. 68.

- ↑ Klapsis 2014, pp. 240–259.

- ↑ Svolopoulos 1978, pp. 343–348.

- ↑ Kitromilides 2008, p. 217.

- ↑ Svolopoulos 1978, p. 349.

- ↑ Steiner 2005, pp. 499–500.

- ↑ Svolopoulos 1978, pp. 349–350.

- ↑ Svolopoulos 1978, pp. 352–358.

- ↑ http://www.mfa.gr/italy/it/

- ↑ http://greece.greekreporter.com/2014/07/18/pm-samaras-has-luncheon-with-italian-pm-renzi-in-florence/

- ↑ http://www.ekathimerini.com/4dcgi/_w_articles_wsite1_1_18/07/2014_541490

- ↑ http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4457770,00.html

- ↑ https://electronicintifada.net/blogs/ali-abunimah/greek-forces-train-israel-syriza-led-government-deepens-alliance

- ↑ http://ea-italy-2011-2015.site/it/news/sociale/9564-presidenza-italia-grecia-una-faccia-una-razza.html

- ↑ http://www.lindro.it/italia-grecia-europa-nellarte-una-faccia-una-razza/?pdf=134418

- ↑ http://eu.greekreporter.gr/?p=16095

- ↑ http://www.ethnos.gr/koinonia/arthro/apokalyptoun_tis_omoiotites_ellinon_kai_italon_me_tin_texni-64035534/

- ↑ Benigno, Franco (2006). "Il Mediterraneo dopo Braudel". In Barcellona, Pietro; Ciaramelli, Fabio. La frontiere mediterranea: tradizioni culturali e sviluppo locale. Bari: Edizioni Dedalo. p. 47.

Sources

- Bell, P. M. H. (1997) [1986]. The Origins of the Second World War in Europe (2nd ed.). London: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-582-30470-3.

- Kitromilides, Paschalis M. (2008) [2006]. Eleftherios Venizelos: The Trials of Statesmanship. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3364-7.

- Klapsis, Antonis (2014). "Attempting to Revise the Treaty of Lausanne: Greek Foreign Policy and Italy during the Pangalos Dictatorship, 1925–1926". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 25 (2): 240–259. doi:10.1080/09592296.2014.907062.

- Plowman, Jeffrey (2013). War in the Balkans: The Battle for Greece and Crete 1940–1941. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78159-248-9.

- Steiner, Zara S. (2005). The Lights that Failed: European International History, 1919–1933. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822114-2.

- Svolopoulos, Konstantinos (1978). "Η εξωτερική πολιτική της Ελλάδος". Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΕ': Νεώτερος ελληνισμός από το 1913 ως το 1941 (in Greek). Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 342–358.

- Verzijl, J. H. W. (1970). International Law in Historical Perspective (Brill Archive ed.). Leyden: A. W. Sijthoff. ISBN 90-218-9050-X.