Fort Warren (Massachusetts)

|

Fort Warren | |

|

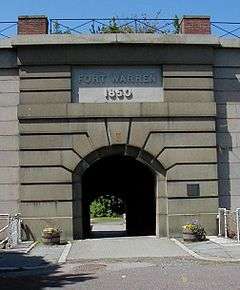

Fort Warren's sally port | |

| |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°19′12.84″N 070°55′39.5″W / 42.3202333°N 70.927639°W |

| Area | 40 acres (16 ha) |

| Built | 1834–1860 |

| Architect | Thayer, Lt. Col. Sylvanus; Army Corps of Engineers |

| Architectural style | Third System fort |

| NRHP Reference # | 70000540[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | August 29, 1970 |

| Designated NHLD | August 29, 1970 |

Fort Warren is a historic fort on the 28-acre (110,000 m2) Georges Island at the entrance to Boston Harbor. The fort is pentagonal star fort, made with stone and granite, and was constructed from 1833–1861, completed shortly after the beginning of the American Civil War. Fort Warren defended the harbor in Boston, Massachusetts, from 1861 through the end of World War II, and during the Civil War served as a prison for Confederate officers and government officials. The fort remained active through the Spanish–American War and World War I, and was re-activated during World War II. It was permanently decommissioned in 1947, and is now a tourist site. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970 as a masterpiece of coastal engineering of the pre-Civil War period, and for its role in the Civil War. It was named for Revolutionary war hero Dr. Joseph Warren, who sent Paul Revere on his famous ride, and was later killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The name was transferred from the first Fort Warren in 1833, which was renamed Fort Winthrop.[2]

Early history

Fort Warren was built from 1833 to 1861 and was completed shortly after the beginning of the American Civil War as part of the third system of US fortifications. The Army engineer in charge during the bulk of the fort's construction was Colonel Sylvanus Thayer, best known for his tenure as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. It was the fifth largest of the 42 third system forts. The overall plan was pentagonal in shape, slightly irregular to make the best use of the island's terrain. The fort features excellent granite work. A demilune (half-moon) battery protecting the north sally port is a rare feature in US forts.[3] The fort was originally designed for over 200 guns, including some mortars and flank howitzers. During the Civil War it was armed with 15-inch and 10-inch Rodman smoothbore guns.[4]

During the Civil War, the island fort served as a prison for captured Confederate army and navy personnel,[5] elected civil officials from the state of Maryland, and Northern political prisoners.

James M. Mason and John Slidell, the Confederate diplomats seized in the Trent affair, were among those held at the fort. Confederate military officers held at Fort Warren included Richard S. Ewell, Isaac R. Trimble, John Gregg, Adam "Stovepipe" Johnson, Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr., and Lloyd Tilghman. High-ranking civilians held at Fort Warren include Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens and Confederate Postmaster General John Henninger Reagan. The prison camp had a reputation for humane treatment of its detainees. When the camp commander's son, Lieutenant Justin E. Dimick, left Fort Warren for active duty in the field with the Second U.S. Artillery, he was given a letter from Confederate officers in the camp urging good care should he be captured. (He was later mortally wounded at Chancellorsville in May, 1863.)

The famous Union marching song John Brown's Body was written at the fort using a tune from an old Methodist camp song, and was performed at a flag-raising there on 12 May 1861. The song was carried to the Army of the Potomac by the men of the "Webster Regiment" (12th Massachusetts Infantry), who had mustered in at Fort Warren. Julia Ward Howe heard this song while visiting Washington, DC. At the suggestion of her minister, Howe was encouraged to write new words. The Battle Hymn of the Republic, which was initially published as a poem, was later matched with the melody of the "John Brown" song and became one of the best remembered songs of the Civil War era. (See also:List of Civil War POW Prisons and Camps)

Post-Civil War through Endicott Period

In the 1870s Fort Warren was upgraded with new barbette batteries on the parapets along with a six-gun external battery; these were armed with Rodman guns.[2] A plaque at the fort states that the southeast bastion was roofed over at this time to create a rare (possibly unique) casemated 15-inch Rodman gun battery. The massive brick arches built to enclose this bastion are impressive.

From 1892 to 1903 Fort Warren was rebuilt to accommodate modern breech-loading rifled guns under the Endicott program. Five batteries were added to the fort, replacing some of the older gun positions, as follows:[4][6]

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

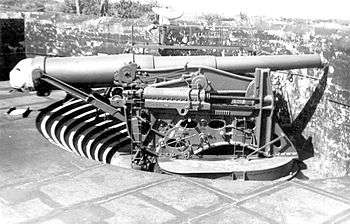

| Adams | 1 | 10-inch gun M1888 | disappearing M1894 | 1899-1914 |

| Bartlett | 4 | 10-inch gun M1888 | disappearing, 2 M1894, 2 M1896 | 1899-1942 |

| Lowell | 3 | 3-inch gun M1898 | masking parapet M1898 | 1900-1920 |

| Plunkett | 2 | 4-inch gun M1896 | pedestal M1896 | 1899-1920 |

| Stevenson | 2 | 12-inch gun M1895 | disappearing M1897 | 1903-1944 |

The two 12-inch (305 mm) and five 10-inch (254 mm) guns were the fort's main armament against enemy battleships. For defense against smaller vessels, particularly to defend nearby mine fields against minesweepers, two 4-inch (102 mm) and three 3-inch (76 mm) guns were included. The 4-inch guns were a Navy design by Driggs-Schroeder, and in the whole US Army coast defense system only Fort Warren and Fort Washington in Maryland had this type of gun.[7] Battery Adams was built of low-quality concrete and was disarmed and abandoned due to deterioration in 1914.[4]

World War I through World War II

Fort Warren was the headquarters of the Coast Defenses of Boston in World War I.[2] In 1917-1918 the four 10-inch guns of Battery Bartlett were removed for potential service as railway artillery on the Western Front. Contrary to some references, no 10-inch railway guns were mounted in time to be shipped to France for World War I.[8] Different 10-inch M1888 guns, including two from Battery Reilly at Fort Adams in Rhode Island and two from storage, replaced these weapons in 1919.[4]

In 1920, with World War I over, several weapon types were withdrawn from Coast Artillery service. These included the 4-inch Driggs-Schroeder guns of Battery Plunkett and the 3-inch Driggs-Seabury guns of Battery Lowell. The 4-inch guns at Fort Warren remained as display pieces at least through 1941.[7] None of these were replaced.[4]

During World War II, the fort served as a control center for Boston Harbor's south mine field, a precaution taken in anticipation of potential attacks by Kriegsmarine U-boats. At that time, Fort Warren was garrisoned by the 241st Coast Artillery Regiment (Harbor Defense), a Massachusetts National Guard unit that was federalized in September, 1940. As new 16-inch batteries were built, particularly Battery Murphy at the East Point Military Reservation, Fort Warren's remaining guns were scrapped in 1942-1944. Fort Warren was permanently decommissioned after 1950. At some point an emplacement of Battery Bartlett was demolished for an access road.

Decommissioning and opening to the public

Fort Warren was owned by the U.S. federal government until 1958, when the state obtained it from the General Services Administration. In 1961, the fort was reopened to the public after initial restoration.

Today, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation maintains and administers the fort, which is the centerpiece of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area. The fort is reachable by ferry from downtown Boston, Hingham, or Hull to Georges Island. Transfers are then available for those who wish to visit some of the other Harbor Islands.

The fort is typically open from early or mid May through Columbus Day weekend. DCR Rangers offer guided tours, or you may explore on your own. An information booth just outside the sally port (the main entrance to the fort) posts information about available activities. The island offers a well-stocked snack bar, water fountains, and a large number of composting toilets. There is also a museum located in the old mine storehouse (the red brick building opposite the ferry dock), a number of picnic tables, and a children's play structure. The tops of several of the walls and several of the casemates and magazines beneath them are open to visitors. The dock side of the fort features two 3-inch rifled guns converted to breechloaders and a memorial to 13 Confederate prisoners who died at the fort. 10-inch Rodman guns, projectiles from the Endicott era, and two World War II 40 mm Bofors guns are also at the fort. The museum includes a demonstration model of a disappearing gun and a Nike-Ajax missile.

Gallery

3-inch Ordnance rifles converted to breechloading saluting guns

3-inch Ordnance rifles converted to breechloading saluting guns Inside the casemated, roofed-over southeast bastion

Inside the casemated, roofed-over southeast bastion Two-gun casemate, southeast bastion

Two-gun casemate, southeast bastion One of the large arches that encloses the southeast bastion

One of the large arches that encloses the southeast bastion A line of arches connecting casemates

A line of arches connecting casemates Memorial to 13 Confederates who died as prisoners at Fort Warren

Memorial to 13 Confederates who died as prisoners at Fort Warren Memorial to Edward Rowe Snow, who fought to preserve Fort Warren

Memorial to Edward Rowe Snow, who fought to preserve Fort Warren Demilune (half-moon) battery defending the sally port

Demilune (half-moon) battery defending the sally port A flank defense

A flank defense Battery Jack Adams, one 10-inch M1888 disappearing gun. Completed 1899, abandoned 1914 due to low-quality concrete.

Battery Jack Adams, one 10-inch M1888 disappearing gun. Completed 1899, abandoned 1914 due to low-quality concrete.

See also

- 9th Coast Artillery (United States)

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Boston

- National Register of Historic Places listings in southern Boston, Massachusetts

- Seacoast defense in the United States

- United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

Notes

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 Fort Warren at NorthAmericanForts.com

- ↑ Weaver, pp. 83-86

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fort Warren at FortWiki.com

- ↑ "NHL nomination for Fort Warren" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- ↑ Berhow, p. 205

- 1 2 Berhow, pp. 84-85

- ↑ US Army Railway Guns in World War I

References

- Berhow, Mark A., Ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Third Edition. McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- Hesseltine, William B., Ed. (1962). Civil War Prisons. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. (This book contains a chapter on Fort Warren's use as POW depot.)

- Howard, F. K. (Frank Key) (1863). Fourteen Months in American Bastiles. London: H.F. Mackintosh. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Marshall, John A. (1871). American Bastille: A History of the Illegal Arrests and Imprisonment of American Citizens.., 8th Ed. Philadelphia: Thomas W. Hartley.

- Schmidt, Jay (2003). Fort Warren: New England's Most Historic Civil War Site. Amherst, NH: Unified Business Technologies Press. ISBN 0-9721489-4-9.

- Stephens, Alexander H. (1998). Recollections - His Diary Kept While a Prisoner at Fort Warren. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071226-8-6. (reprint edition)

- Weaver II, John R. (2001). A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867. McLean, VA: Redoubt Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 1-57510-069-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Warren (Massachusetts). |

- Island Facts: Georges Island - Includes Fort Warren information from the National Park Service

- Boston Harbor Islands: Georges Island

- Fort Warren at FortWiki.com

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- FortWiki, lists most CONUS and Canadian forts

- Harbor Defenses of Boston at NorthAmericanForts.com