Kingdom of Albania (medieval)

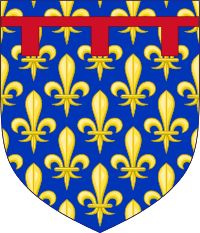

| Kingdom of Albania | ||||||||||||

| Regnum Albaniae Mbretëria e Arbërisë | ||||||||||||

| Dependency of the Angevin Kingdom of Naples | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Kingdom of Albania at its maximum extent | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Durazzo (Dyrrhachium, modern Durrës) | |||||||||||

| Languages | Albanian, Lombard | |||||||||||

| Religion | Catholic, Orthodox | |||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||

| King, Lord and later Duke | ||||||||||||

| • | 1272–1285 | Charles I | ||||||||||

| • | 1366–1368 | Louis | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | |||||||||||

| • | Established | 1272 | ||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1368 | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Albania (Albanian: Mbretëria e Arbërisë, Latin: Regnum Albaniae) was established by Charles of Anjou in the Albanian territory he conquered from the Despotate of Epirus in 1271. He took the title of "King of Albania" in February 1272. The kingdom extended from the region of Durrës (then known as Dyrrhachium) south along the coast to Butrint. A major attempt to advance further in direction of Constantinople, failed at the Siege of Berat (1280–1281). A Byzantine counteroffensive soon ensued, which drove the Angevins out of the interior by 1281. The Sicilian Vespers further weakened the position of Charles, and the Kingdom was soon reduced by the Epirotes to a small area around Durrës. The Angevins held out here, however, until 1368, when the city was captured by Karl Thopia. In 1392 Karl Thopia's son surrendered the city and his domains to the Republic of Venice.

History

Background

During the conflict between the Despotate of Epirus and the Empire of Nicaea in 1253, lord Golem of Kruja was initially allied with Epirus. Golem's troops had occupied the Kostur area trying to prevent the Nicaean forces of John Vatatzes from entering Devoll. Vatatzes managed to convince Golem to switch sides and a new treaty was signed between the parties where Vatatzes promised to guarantee Golem's autonomy. The same year Despot of Epirus Michael II signed a peace treaty with Nicaea acknowledging their authority over west Macedonia and Albania. The fortress of Krujë was surrendered to Nicaea, while the Nicean emperor acknowledged the old privileges and also granted new ones. The same privileges were confirmed later by his successor Theodore II Laskaris.[1]

The Nicaeans took control of Durrës from Michael II in 1256. During the winter of 1256–57, George Akropolites tried to reinstall Byzantine authority in the area of Arbanon. Autonomy was thus banished and a new administration was imposed. This was in contrast to what the Nicaeans had promised before. The local Albanian leaders revolted and on hearing the news, Michael II also denounced the peace treaty with the Nicaea. With the support of Albanian forces he attacked the cities of Dibra, Ohrid and Prilep. In the meantime Manfred of Sicily profited from the situation and launched an invasion into Albania. His forces, led by Philip Chinardi, captured Durrës, Berat, Vlorë, Spinarizza and their surroundings and the southern coastline of Albania from Vlorë to Butrint.[2] Facing a war in two fronts, despot Michael II came to terms with Manfred and became his ally. He recognized Manfred's authority over the captured regions which were ceded as a dowry gift following the marriage of his daughter Helena to Manfred.[2][3]

Following the defeat of Michael II's and Manfred's forces in the Battle of Pelagonia, the new Nicaean forces continued their advance by capturing all of Manfred's domains in Albania, with the exception of Durrës. However, in September 1261, Manfred organized a new expedition and managed to capture all his dominions in Albania and he kept them until his death in 1266.[4] Manfred respected the old autonomy and privileges of the local nobility and their regions. He also integrated Albanian nobles into his administration, as was the case with Andrea Vrana who was the general captain and governor of Durrës and the neighboring region of Arbanon. Albanian troops were also used by Manfred in his campaigns in Italy. Manfred appointed Philippe Chinard as the general-governor of his dominions in Albania. Initially based in Corfu, Chinard moved his headquarters to Kanina, the dominant center of the Vlorë region. There he married a relative of Michael II.[5]

Creation

After defeating Manfred's forces in the Battle of Benevento in 1266, the Treaty of Viterbo of 1267 was signed, with Charles of Anjou acquiring rights on Manfred's dominions in Albania,[6][7] together with rights he gained in the Latin dominions in the Despotate of Epirus and in the Morea.[8] Upon hearing the news of Manfred's death in the battle of Benevento, Michael II conspired and managed to kill Manfred's governor Philippe Chinard, with the help of Chinard's wife, but he could not capture Manfred's domains. Local noblemen and commanders refused to surrender Manfred's domains in Albania to Michael II. They gave the same negative response to Charles' envoy, Gazo Chinard in 1267, when following the articles of the Treaty of Viterbo, he asked for them to surrender Manfred's dominions in Albania.[9]

After the failure of the Eighth Crusade, Charles of Anjou returned his attention to Albania. He began contacting local Albanian leaders through local catholic clergy. Two local catholic priests, namely John from Durrës and Nicola from Arbanon, acted as negotiators between Charles of Anjou and the local noblemen. During 1271 they made several trips between Albania and Italy eventually succeeding in their mission.[10] On 21 February 1272,[6] a delegation of Albanian noblemen and citizens from Durrës made their way to Charles' court. Charles signed a treaty with them and was proclaimed King of Albania "by common consent of the bishops, counts, barons, soldiers and citizens" promising to protect them and to honor the privileges they had from Byzantine Empire.[11] The treaty declared the union between the Kingdom of Albania (Latin: Regnum Albanie) with the Kingdom of Sicily under King Charles of Anjou (Carolus I, dei gratia rex Siciliae et Albaniae).[10] He appointed Gazzo Chinardo as his Vicar-General and hoped to take up his expedition against Constantinople again. Throughout 1272 and 1273 he sent huge provisions to the towns of Durrës and Vlorë. This alarmed the Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos, who began sending letters to local Albanian nobles, trying to convince them to stop their support for Charles of Anjou and to switch sides. The Albanian nobles sent those letter to Charles who praised them for their loyalty. Then, Michael VIII's hopes of stopping the advance of Charles were laid on the influence of Pope Gregory X. Gregory had high hopes of reconciling Europe, unifying the Greek and Latin churches, and launching a new crusade: to that end, he announced the Council of Lyon, to be held in 1274, and worked to arrange the election of an Emperor, so he ordered Charles to stop his operations.[12]

Charles of Anjou imposed a military rule on Kingdom of Albania. The autonomy and privileges promised in the treaty were "de facto" abolished and new taxes were imposed. Lands were confiscated in favor of Anjou nobles and Albanian nobles were excluded from their governmental tasks. In an attempt to enforce his rule and local loyalty, Charles I, took as hostages the sons of local noblemen. This created a general discontent in the country and several Albanian noblemen began contacting Byzantine Emperor Michael VII who promised them, to acknowledge their old privileges.[13]

Byzantine offensive

As Charles I's intentions for a new offensive were stopped by the Pope and there was a general discontent within Albania, Michael VIII caught the occasion and began a campaign in Albania in late 1274. Byzantine forces helped by local Albanian noblemen captured the important city of Berat and later on Butrint. On November 1274, the local governor reported to Charles I that the Albanian and Byzantine forces had besieged Durrës. The Byzantine offensive continued and captured the port-city of Spinarizza. Thus Durrës alongside the Krujë and Vlora regions became the only domains in mainland Albania which were still under Charles I's control, but they were landlocked and isolated from each other. They could communicate with each other only by sea but the Byzantine fleet based in Spinarizza and Butrint kept them under constant pressure. Charles also managed to keep the island of Corfu.[14][15]

Michael VIII also scored another important diplomatic victory on Charles I by agreeing to unite the two churches in the Second Council of Lyon in 1274. Enthusiastic from the results of the council, Pope Gregory X, forbade any attempt by Charles on Michael VIII's forces. Under these circumstances Charles of Anjou was forced to sign a truce with Michael VIII in 1276.[14]

Angevin counteroffensive

The Byzantine presence in Butrint alarmed Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas the Despot of Epirus. He contacted Charles of Anjou and his vassal William II of Villehardouin who was at that time the prince of Achaea. Nikephoros I promised to make an oath of homage to Charles of Anjou in return for some land property in Achaia. In 1278 Nikephoros I's troops captured the city of Butrint. In March 1279 Nikephoros I declared himself a vassal of Charles of Anjou and surrendered to him the castles of Sopot and Butrint. As a pledge, Nikephoros I delivered his own son to the Angevin castellan of Vlorë to be held as hostage. Ambassadors were exchanged in this occasion, but Charles did not wait for the formalities to end; instead he ordered his captain and vicar-general at Corfu to capture not only Butrint, but everything that once belonged to Manfred and now were under the Despotate of Epirus.[16]

At the same time Charles began creating a network of alliances in the area in the brick of the new offensive, which would have pointed first to Thessaloníki and later to Constantinople. He entered in alliance with the kings of Serbia and Bulgaria.[17] He also tried to get the support of the local Albanian nobles. After continuous requests from other Albanian nobles, he liberated from Neapolitan prisons a number of Albanian nobles who were arrested before being accused of collaborating with Byzantine forces. Among them were Gjin Muzaka, Dhimitër Zogu and Guljem Blinishti. Gjin Muzaka especially was important to Charles' plans because the Muzaka family territories were around city of Berat. They were liberated, but were ordered to send their sons as hostages in Naples.[18]

On August 1279, Charles of Anjou appointed Hugo de Sully as Captain and Vicar-General of Albania, Durrës, Vlorë, Sopot, Butrint and Corfu In the following months a great Angevin counteroffensive was prepared.[17] A lot of materials and men including Saracen archers and siege engineers were sent to de Sully, who had captured Spinarizza from Byzantine forces making it his headquarters.[19] The first goal of the expedition was the recapture of the city of Berat, which had been under Byzantine control since 1274. However, Charles' preparations were restrained by Pope Nicholas III who had forbidden Charles from attacking the Byzantine Empire. However, Pope Nicholas III died on August 1280 and for more than six months the Pope's seat was vacant. This gave Charles an opportunity to move on. During Autumn 1280 he gave the order to Hugo de Sully to move on.[20] In December 1280 Angevin forces captured the surroundings of Berat and besieged its castle.[19]

Byzantine counteroffensive

The Byzantine Emperor was hoping for the Pope to stop his Latin adversaries. In fact after the death in 1276 of Pope Gregory X, the main supporter of the union of the churches, his successors maintained the same course and this restricted Charles' movements. However, in February 1281 Charles of Anjou achieved a diplomatic victory by imposing a French Pope, as the head of the Catholic Church. The Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII was excommunicated by the new Pope and Charles' expedition against him blessed as a new crusade.[17]

The situation was very complicated for Michael VIII; however, he sent help to the besieged garrison. The Byzantine army which also included Turkish mercenaries arrived near Berat in March 1281. They were under orders to avoid pitched battle and to focus on ambushes and raids.[21] They managed to defeat Angevin forces by capturing first their commander Hugo de Sully in an ambush. This spread panic throughout his army, routing them from the battlefield. The Angevin army lost the major part of its forces and only a small part found refuge in the Kaninë castle, which was in Angevin hands.[22] The Byzantine army continued its advance further into the territory. They besieged the Angevin bases of Vlorë, Kaninë, and Durrës but could not capture them. The Albanian nobles in the region of Krujë allied themselves with the Byzantine Emperor and he granted them a charter of privileges for their city and bishopric.[23]

Charles' preparations and Sicilian Vespers

Treaty of Orvieto

The failure of Hugo de Sully's expedition convinced Charles of Anjou that an invasion of the Byzantine Empire by land was not feasible,[21] and he thus considered a naval expedition against Byzantium. He found an ally in Venice and in July 1281, the Treaty of Orvieto formalized this collaboration. Its stated purpose was the dethronement of Michael VIII in favor of the titular Latin emperor Philip of Courtenay and the forcible establishment of the Union of the Churches, bringing the Greek Orthodox Church under the authority of the Pope. Its principal motivation, however, was to re-establish the Latin Empire, under Angevin domination, and to restore Venetian commercial privileges in Constantinople.[24]

Under the terms of the treaty, Philip and Charles were to supply 8,000 troops and cavalry, and sufficient ships to transport them to Constantinople. Philip, the Doge of Venice Giovanni Dandolo, and Charles himself or Charles' son, Charles, Prince of Salerno, were to personally accompany the expedition. In practice, Charles would have supplied almost all of the troops, Philip having little or no resources of his own. The Venetians would supply forty galleys as escorts for the invasion fleet, which was to sail from Brindisi no later than April 1283. Upon Philip's restoration to the throne, he was to confirm the concessions of the Treaty of Viterbo and the privileges granted to Venice at the founding of the Latin Empire, including recognition of the Doge as dominator of "one-fourth and one-eighth of the Latin Empire."[25]

A second document was also drawn up to organize a vanguard to precede the main expedition of 1283. Charles and Philip were to supply fifteen ships and ten transports with about 300 men and horses. The Venetians were to provide fifteen warships for seven months of the year. These forces would make war against Michael VIII and "other occupiers" of the Latin Empire (presumably the Genoese), and would meet in Corfu by 1 May 1282, paving the way for the next year's invasion.[25]

The two treaties were signed by Charles and Philip on 3 July 1281, and were ratified by the Doge of Venice on 2 August 1281.[25]

Sicilian Vespers

On Easter Monday 30 March 1282, in Sicily the local people began attacking French forces in an uprising which would become known as the Sicilian Vespers. The massacre went on for weeks throughout the island and they also destroyed the Angevin fleet gathered in the harbor of Messina which Charles had intended to use in the new expedition against Byzantium. Charles tried to suppress the uprising, but on 30 of August 1282, Peter III of Aragon landed in Sicily, it was clear that Charles had no more chances of attacking Byzantium.[26] In September 1282, the Angevin house forever lost Sicily. His son Charles II of Naples was captured by the Aragonese army in the Battle of the Gulf of Naples and was still a prisoner when his father, Charles of Anjou, died on 7 January 1285. Upon his death Charles left all of his domains to his son, who at the time was held by the Catalans. He was kept as prisoner up to 1289, when he was finally released.[27]

Restoration

Loss of Durrës

The Angevin resistance continued for some years in Kaninë, Durrës and Vlorë. However Durrës fell in Byzantine hands in 1288 and in the same year Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos renewed the privileges that his predecessor had granted to the Albanians in the Krujë region.[23] Kaninë castle was the last to fall to the Byzantines probably in 1294, while Corfu and Butrint remained in Angevin hands at least up to 1292.[28] In 1296 Serbian king Stephen Milutin took possession of Durrës. In 1299 Andronikos II Palaiologos married his daughter Simonis to Milutin and the lands he had conquered were considered as a dowry gift.[29]

Recapture of Durrës

Although the Albanian territories were lost, the notion and rights of the Kingdom of Albania continued for the Angevins for a long time after Charles of Anjou's death. The Kingdom was inherited by Charles II after the death of his father in 1285. In August 1294, Charles II passed his rights on Albania to his son Philip I, Prince of Taranto. In November 1294, Philip I was married to the daughter of the Epirote Despot Nikephoros I, renewing the old alliance between the two states.[30] His plans of recovering old Angevin domains were paused for a while when in 1299 Philip of Taranto became a prisoner of Frederick III of Sicily in the Battle of Falconaria. However, after his release in 1302, he claimed his rights on the Albanian kingdom and began preparations to recover it. He gained the support of local Albanian Catholics who preferred a Catholic Italian power as their protector instead of the Orthodox Serbs and Greeks, as well as the support of Pope Benedict XI. In the summer of 1304, Serbs were expelled from the city of Durrës by its citizens and local nobles, who in September submitted themselves to Angevin rule. Philip and his father Charles II renewed the old privileges that Charles of Anjou had promised to the citizens and nobility of Durrës. In 1305, further extensive exemptions from dues and taxes were granted to the citizens of Durrës and the local nobles from Charles II.[31]

The territory of the Kingdom of Albania under Philip of Taranto was restricted to roughly the modern Durrës District. In an attempt to resolve the tensions between the house of Anjou and the Aragonese, the Kingdom of Albania and the lands in Achaea under Angevin dominion were offered in exchange for the Kingdom of Trinacria ruled by Frederick II. These negotiations lasted some years but were abandoned in 1316.[32]

Upon the death of Philip of Taranto in 1332, there were various claims on his domains within the Angevin family. The rights of the Duchy of Durazzo (Durrës) and the Kingdom of Albania together were given to John of Gravina with a sum of 5,000 pounds of gold.[33] After his death in 1336, his dominions in Albania passed to his son Charles, Duke of Durazzo.

During this period there were different Albanian noble families who began consolidating their power and domains. One of them was the Thopia family whose domains were in central Albania. The Serbs were pressing hard in their direction and the Albanian nobles found a natural ally in the Angevins.[34] Alliance with Albanian leaders was also crucial to the safety of the Kingdom of Albania, especially during the 1320s and 1330s. Most prominent among these leaders were the Thopias, ruling in an area between the rivers Mat and Shkumbin,[35] and the Muzaka family in the territory between the rivers Shkumbin and Vlorë.[36] They saw the Angevins as protectors of their domains and made alliances. During 1336–1337 Charles had various successes against Serb forces in central Albania.[37]

Last decades

The pressure of the Serbian Kingdom on the Kingdom of Albania grew especially under the leadership of Stefan Dušan. Although the fate of city of Durrës, the capital of the Kingdom, is unknown, by 1346 all Albania was reported to be under the rule of Dushan.[34] In 1348, Charles, Duke of Durazzo, was decapitated by his cousin Philip II, Prince of Taranto, who also inherited his rights on the Kingdom of Albania. Meanwhile, in Albania, after the death of Dušan, his empire began to disintegrate and, in central Albania, the Thopia family under Karl Topia, claimed rights to the Kingdom of Albania. In fact Karl Thopia's father was married to Helen of Anjou and was recognized as Count of Albania.[38] Karl Thopia took Durrës from the Angevins in 1368 with the consensus of its citizens. In 1376 Louis of Évreux, Duke of Durazzo who had gained the rights on the Albanian Kingdom from his second wife, attacked and conquered the city, but in 1383, Thopia took once again control of the city.[39]

In 1385 the city of Durrës was captured by Balša II. Topia called for Ottoman help and Balša's forces were defeated in the Battle of Savra. Topia recaptured the city of Durrës the same year and held it until his death in 1388. Afterwards, the city of Durrës was inherited by his son Gjergj, Lord of Durrës. In 1392 Gjergj surrendered the city of Durrës and his domains to the Republic of Venice.[40]

Government

The kingdom of Albania was a distinct entity from the Kingdom of Naples. The kingdom had the nature of a military oriented political structure. It had its own structure and organs of government which was located in Durrës.[41] At the head of this governmental body was the captain-general who had the status of a viceroy. These persons usually had the title of capitaneus et vicarius generalis and were the head of the army also, while the local forces were commanded by persons who held the title marescallus in partibus Albaniae.[41]

The royal resources, especially income from salt production and trade, were paid to the thesaurius of Albania. The port of Durrës and sea trade were essential to the kingdom. The port was under the command of prothontius and the Albanian fleet had its own captain. Other offices were created and functioned under the authority of the viceroy.[41]

With the attrition of the territory of the kingdom, the persons appointed as captain-generals began losing their powers, becoming more like governors of Durrës, than representatives of the king.[41]

The role of local Albanian lords became more and more important to the fate of the kingdom and the Angevins integrated them into their military structure especially in the second phase of the kingdom. When Philip of Taranto returned in 1304, one Albanian noble, Gulielm Blinishti, was appointed head of Angevin army in the Kingdom of Albania with the title marascallum regnie Albaniae.[42] He was succeeded in 1318 by Andrea I Muzaka.[43] From 1304 on, other western titles of nobility were bestowed by the Angevins upon the local Albanian lords.[44][45]

Although the Angevins tried to install a centralized state apparatus, they left great autonomy to the Albanians cities. In fact, in 1272 it was Charles of Anjou himself who recognized the old privileges of Durrës' community.

Religion

Historically the territory where the Kingdom of Albania lay was subject to different metropolitan powers such as Antivari, Durrës, Ohrid and Nicopolis, where Catholicism, Greek, Serb and Bulgarian Churches applied their power interchangeably or sometimes even together. The presence of the kingdom reinforced the influence of Catholicism and the conversion to its rite, not only in the region of Durrës but also in other parts of the country.[46]

The Archbishopric of Durrës was one of the primary bishoprics in Albania and before the Great Schism (1054), it had 15 episcopal sees under its authority. After the split it remained under the authority of Eastern Church while there were continuous, but fruitless efforts from the Roman church to convert it to the Latin rite. However, things changed after the fall of Byzantine Empire in 1204. In 1208, a Catholic archdeacon was elected for the archbishopric of Durrës. After the reconquest of Durrës by the Despotate of Epirus in 1214, the Latin Archbishop of Durrës was replaced by an Orthodox archbishop. After his death in 1225, various nearby metropolitan powers fought over the vacant seat. At last a Nicean archbishop was appointed in 1256 but he could not effectively run its office since, in 1258, the city was captured by Manfred.[47]

After the creation of Kingdom of Albania in 1272, a Catholic political structure was a good basis for the papal plans of spreading Catholicism in the Balkans. This plan found also the support of Helen of Anjou, a spouse of King Stefan Uroš I and cousin of Charles of Anjou, as Queen consort of the Serbian Kingdom, who was at that time ruling territories in North Albania. Around 30 Catholic churches and monasteries were built during her rule in North Albania and in Serbia.[48] New bishoprics were created especially in North Albania, with the help of Helen of Anjou.[49]

Durrës became again a Catholic archbishopric in 1272. Other territories of the Kingdom of Albania became Catholic centers as well. Butrint in the south, although dependent on Corfu, became Catholic and remained as such during 14th century. The same happened to Vlorë and Krujë as soon as the Kingdom of Albania was created.[50]

A new wave of Catholic dioceses, churches and monasteries were founded, a number of different religious orders began spreading into the country, and papal missionaries also reached the territories of the Kingdom of Albania. Those who were not Catholic in Central and North Albania converted and a great number of Albanian clerics and monks were present in the Dalmatian Catholic institutions.[51]

However, in Durrës the Byzantine rite continued to exist for a while after Angevin conquest. This double-line of authority created some confusion in the local population and a contemporary visitor of the country described Albanians as nor they are entirely Catholic or entirely schismatic. In order to fight this religious ambiguity, in 1304, Dominicans were ordered by Pope Benedict XI to enter the country and to instruct the locals in the Latin rite. Dominican priests were also ordered as bishops in Vlorë and Butrint.[52]

Among the Catholic orders operating during that period in Albania, one could mention the Franciscan order, Carmelites, Cistercians and Premonstratensians. Also from time to time, the local bishops were appointed from different orders as different popes had their favorites among them.[53]

Krujë became an important center for the spread of Catholicism. Its bishopric had been Catholic since 1167. It was under direct dependence from the pope and it was the pope himself who consecrated the bishop.[54] Local Albanian nobles maintained good relations with the Papacy. Its influence became so great, that it began to nominate local bishops.

The Catholic cause had a drawback while Stephan Dushan ruled in Albania. The Catholic rite was called Latin heresy and Dushan's code contained harsh measures against them. However, the persecutions of local catholic Albanians did not begin in 1349 when the Code was promulgated, but much earlier, at least since the beginning of 14th century. Under these circumstances the relations between local Catholic Albanians and the papal curia became very close.[55]

Between 1350 and 1370, the spread of Catholicism in Albania reached its peak. At that period there were around seventeen Catholic bishoprics in the country, which acted not only as centers for Catholic reform within Albania, but also as centers for missionary activity in the neighboring areas, with the permission of the pope.[51]

Society

While the Byzantine Pronoia was the dominant form in the country, the Angevins introduced the Western type of feudalism. In the 13th and 14th centuries, pronoiars earned a great number of privileges and attributes, taking power away from the central authority. The benefit earned by the pronoiars from their land increased. Pronoiars began to collect land taxes for themselves which was an attribute of the state. They also began to exercise administrative authorities which replaced the state's, such as the ability to gather workers, guards, soldiers, and sometimes their own judges. In the 13th century, it was common for pronoiars to arrogate their own right to trial, initially for petty issues and then for serious crimes, taking away central authority from the main prerogatives to the practice of sovereignty.[56]

By the 14th century, the pronoia had reached the status of feudal possession. It could now be passed on to succession, split, and sold. The pronoia increasingly rarely fulfilled the military needs of the state.[56] Alongside the pronoiars were landowners who owned large tracts of land worked by farmers. The landownership also included pronoiars from Durrës, Shkodër, and Drisht. Citizens of Durrës owned property and grazing land in the nearby mountain of Temali. The splitting, inheritance, and selling of the property was a common occurrence.[57]

The feudal possessions in Albania, as in the West and the Byzantine Empire, were made up of two parts: the land of the peasants and the land which was directly owned by the lords of the land. The peasant's land was not centralized, but was split into many small plots, often far from each other. The lord's land was continually expanded along the same lines that the aristocracy strengthened.[57]

Land was also centralized under religious institutions, including monasteries and bishoprics. Unlike the 12th century, where the area under control was donated by the central authority, after the 12th century, most donors of land to the monasteries and bishoprics were small and large landowners.[57] By the beginning of the 14th century, monasteries and bishoprics had been able to collect large sums of land funds.[58] The income of the monasteries came mainly from agricultural products, but a small part also came from craftwork and other activities. A central source of income to the church were from taxes gathered in kind and in cash. A good of portion went to Rome or Constantinople. The delivery of bonds was one of the causes of friction between the local clergy and the Pope in Rome or the Patriarch in Constantinople.[59]

In an effort to find additional means of finance, especially in times of war, the central authority imposed high taxes on the population. The pyramid of society depended upon the work of the farmers. Besides the main category of farmers, categories of farmers included "free" farmer and "foreign" farmers. They were deprived of land and any form of possession and were therefore not registered, placing them in a feud for the quality of wages. Eventually, they received a piece of land for which they paid their duties, and were fused with the main category of farmers.[59]

The feudal duties of the peasant were not the same for all the Albanian areas but differed according to the terrain. The systems of payment in kind or in cash also changed accordingly, but the strengthening of the nobility against the central authority in the 13th century caused the payments in cash to increase compared to payments in kind. From the 12th to the 14th century, the vertical shift of power to the nobles was deepened. Not only were the plains brought under the control of the nobles, but also mountainous areas. The feudal possessions also began to include communal areas such as forests, pastures, and fisheries. This evolution took place during the period of Byzantine decline and saw the conversion of the pronoia into an estate very similar to the feudal one.[60]

The overwhelming majority of the population under the lords' rule was made up of agricultural workers. Contemporary sources reveal that in large parts of Albania, the village population had fallen to the status of serfdom. An anonymous traveler in 1308 revealed that farmers in the regions of Këlcyrë, Tomorricë, Stefaniakë, Kunavë, and Pultë of Dibra worked the lands and vineyards of their respective lords, turned over their products, and performed household work for them. The Byzantine historian Kantakouzenos, testifies that the power of the lords of these areas depended mostly on livestock which were present in large numbers.[61]

Cities

During the 13th century, many cities in Albania made the move from being primarily military strongholds to becoming urban centers. Unable to contain the development inside the city walls, many cities expanded outside them. Quarters outside the walls began to form, called proastion and suburbium and became important economic centers. In these quarters, trade took place and shops along with workshops were centered here. Eventually, many of these quarters too were surrounded by walls to protect them. In order to secure a supply of water, cisterns in open, safe spaces were used to gather water. In some unique cases, water was also gathered from nearby rivers.[62]

In the first half of the 14th century, the population of the cities grew greatly. Durrës is estimated to have had 25,000 inhabitants. The city became a center which attracted inhabitants from the rural areas.[62] Durrës is known to have had a large number of inhabitants who came from the surrounding villages. Those farmers who migrated to the city were often forced to pay a fixed payment or to make up for this payment by working in a commune. Along with the farmers came noblemen from the surrounding areas, who either migrated permanently or spent a large amount of time in the cities to look after their economic interests. Many had possessions, stores, and houses in the city. The movement of noblemen to urban areas became normal and they were eventually integrated into the city become citizens and often taking government positions.[63]

Architecture

The spread of Catholicism affected the architecture of religious buildings, with a new Gothic style, mainly in the Center and North Albania. These areas were attached to the Catholic church and thus had greater Western connections. Both the Catholic and Orthodox churches operated in Durrës and the surrounding areas, and therefore both Western and Byzantine architectural styles were followed.[64] Western architecture could also be found in areas where Western rulers had possessions. Churches built in this form were built in Upper and Central Albania and were characterized by an emphasis on an East-West longitudinal axis with circular or rectangular apses. Among the most notable architectural monuments of this period include the Church of Shirgj Monastery near the village of Shirgj near Shkodër, the Church of Saint Mary in Vau i Dejës, and the Church of Rubik.[65] The former two churches were built in the 13th century AD while the latter in the 12th century AD. Most of the churches built in this period were decorated with murals.[65]

List of rulers

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kingdom of Albania (medieval). |

Kings of Albania

- Charles I 1272–1285

- Charles II 1285–1294

Charles surrendered his rights to Albania to his son Philip in 1294. Philip reigned as Lord of the Kingdom of Albania.

Lords of the Kingdom of Albania

In 1332, Robert succeeded his father, Philip. Robert's uncle, John, did not wish to do him homage for the Principality of Achaea, so Robert received Achaea from John in exchange for 5,000 ounces of gold and the rights to the diminished Kingdom of Albania. John took the style of Duke of Durazzo.

Dukes of Durazzo

In 1368, Durazzo fell to Karl Topia, who was recognized by Venice as Prince of Albania.

Captains and Vicars-General of the Kingdom of Albania

These officers were styled Capitaneus et vicaris generalis in regno Albaniae.[41]

- Gazo Chinard (1272)

- Anselme de Chaus (May 1273)

- Narjot de Toucy (1274)

- Guillaume Bernard (23 September 1275)

- Jean Vaubecourt (15 September 1277)

- Jean Scotto (May 1279)

- Hugues de Sully le Rousseau (1281)

- Guillaume Bernard (1283)

- Gui de Charpigny (1294)

- Ponzard de Tournay (1294)

- Simon de Mercey (1296)

- Guillaume de Grosseteste (1298)

- Geoffroy de Port (1299)

- Rinieri da Montefuscolo (1301)

Marshals of the Kingdom of Albania

These officers were styled Marescallus in regni Albaniae.[41][66]

- Guillaume Bernard

- Philip d'Artulla (Ervilla)

- Geoffroy de Polisy

- Jacques de Campagnol

- Gulielm Blinishti (1304)

- Andrea I Muzaka (1318)

References

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 202

- 1 2 Setton (1976), p. 81

- ↑ Ducellier (1999), p. 791-792

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 205

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 205-206

- 1 2 Ducellier (1999), p. 793

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 12

- ↑ Jacobi (1999), p. 533

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 206

- 1 2 Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 207

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 15

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 15-17

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 208-210

- 1 2 Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 201

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 18

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 18-23

- 1 2 3 Nicol (2010), p. 25

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 211

- 1 2 Setton (1976), p. 136

- ↑ Nicol (1992), p. 206

- 1 2 Bartusis (1997), p. 63

- ↑ Setton (1976), p. 137

- 1 2 Nicol (2010), p. 27

- ↑ Nicol (1992), p. 208-209

- 1 2 3 Nicol (1992), p. 208

- ↑ Setton (1976), p. 140

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 33.

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 28

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 67-68

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 44-47

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 68

- ↑ Abulafia (1996), Intercultural contacts in the medieval Mediterranean, pp.1-13

- ↑ Nicol (2010), p. 99

- 1 2 Nicol (2010), p. 128

- ↑ Norris (1993), p.36

- ↑ Fine (1994), p. 290

- ↑ Abulafia (1996), The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume VI: c. 1300-c. 1415, p. 495

- ↑ Nicolle (1988), p.37

- ↑ Fine (1994), p. 384

- ↑ O'Connell (2009), p.23

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lala (2008), p.21

- ↑ Lala (2008), p.138

- ↑ Lala (2008), p.136.

- ↑ Castellan (2002), p. 25

- ↑ Pollo (1974), 54

- ↑ Lala (2008), p.52

- ↑ Lala (2008), p. 54-55

- ↑ Lala (2008), p. 91-95

- ↑ Lala (2008) p. 155

- ↑ Lala (2008), p. 147-148

- 1 2 Lala (2008), p. 146

- ↑ Lala (2008), p. 149-153

- ↑ Lala (2008), p. 154

- ↑ Lala (2008), p. 157

- ↑ Lala (2008), p. 118-119

- 1 2 Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 220.

- 1 2 3 Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 221.

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), pp. 221-222.

- 1 2 Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 222.

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 223.

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 224.

- 1 2 Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 225.

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 226.

- ↑ Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 314

- 1 2 Anamali & Prifti (2002), p. 315

- ↑ Lala (2008), pp. 136 and 138.

Sources

- Abulafia, David (1996), "Intercultural contacts in the medieval Mediterranean", in Arbel, Benjamin, Intercultural contacts in the medieval Mediterranean, Psychology Press, pp. 1–13, ISBN 978-0-7146-4714-2

- Abulafia, David (1996), "The Italian South", in Jones, Michael, The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume VI: c. 1300-c. 1415, Cambridge University Press, pp. 488–514, ISBN 978-0-521-36290-0

- Anamali, Skënder; Prifti, Kristaq (2002). Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime (in Albanian). Botimet Toena. ISBN 978-99927-1-622-9.

- Bartusis, Mark C. (1997), The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society 1204–1453, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-1620-2

- Castellan, Georges (2002), Histoire de l'Albanie et des albanais, Editions ARMELINE, ISBN 978-2-910878-20-7

- Ducellier, Alain (1999), "Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria", in Abulafia, David, The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume V: c. 1198-c. 1300, Cambridge University Press, pp. 779–795, ISBN 0-521-36289-X

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5

- Frachery, Thomas (2005), Le règne de la Maison d'Anjou en Albanie (1272–1350), Rev. Akademos, pp. 7–26

- Jacobi, David (1999), "The Latin empire of Constantinople and the Frankish states in Greece", in Abulafia, David, The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume V: c. 1198-c. 1300, Cambridge University Press, pp. 525–542, ISBN 0-521-36289-X

- Lala, Etleva (2008), Regnum Albaniae, the Papal Curia, and the Western Visions of a Borderline Nobility (PDF), Central European University, Department of Medieval Studies

- Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42894-1.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (2010), The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-13089-9

- Nicolle, David (1988), Hungary and the fall of Eastern Europe 1000-1568, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85045-833-6

- Norris, H. T. (1993), Islam in the Balkans: religion and society between Europe and the Arab world, University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 978-0-87249-977-5

- O'Connell, Monique (2009), Men of empire: power and negotiation in Venice's maritime state, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-9145-8

- Pollo, Stefanaq (1974), Histoire de l'Albanie, des origines à nos jours Volume 5 of Histoire des nations Collection Histoire des nations européennes Histoire des nations européennes, Horvath, ISBN 978-2-7171-0025-9

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1976), The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume I: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, DIANE Publishing, ISBN 978-0-87169-114-9