Cretan War (205–200 BC)

| Cretan War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Greece and the Aegean circa 201 BC. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Macedonia, Hierapytna, Olous, Aetolia, Spartan pirates, Acarnania |

Rhodes, Pergamum, Byzantium, Cyzicus, Athens, Knossos | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

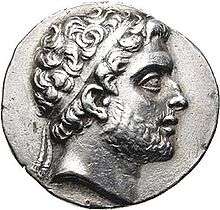

Philip V, Dicaearchus, Nicanor the Elephant |

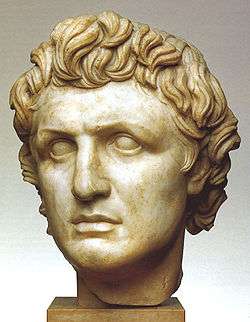

Attalus I, Theophiliscus † Cleonaeus | ||||||||

The Cretan War (205–200 BC) was fought by King Philip V of Macedon, the Aetolian League, many Cretan cities (of which Olous and Hierapytna were the most important) and Spartan pirates against the forces of Rhodes and later Attalus I of Pergamum, Byzantium, Cyzicus, Athens, and Knossos.

The Macedonians had just concluded the First Macedonian War and Philip, seeing his chance to defeat Rhodes, formed an alliance with Aetolian and Spartan pirates who began raiding Rhodian ships. Philip also formed an alliance with several important Cretan cities, such as Hierapytna and Olous. With the Rhodian fleet and economy suffering from the depredations of the pirates, Philip believed his chance to crush Rhodes was at hand. To help achieve his goal, he formed an alliance with the King of the Seleucid Empire, Antiochus the Great, against Ptolemy V of Egypt (the Seleucid Empire and Egypt were the other two Diadochi states). Philip began attacking the lands of Ptolemy and Rhodes's allies in Thrace and around the Propontis.

In 202 BC, Rhodes and her allies Pergamum, Cyzicus, and Byzantium combined their fleets and defeated Philip at the Battle of Chios. Just a few months later, Philip's fleet defeated the Rhodians at Lade. While Philip was plundering Pergamese territory and attacking cities in Caria, Attalus I of Pergamum went to Athens to try to create a diversion. He succeeded in securing an alliance with the Athenians, who immediately declared war on the Macedonians. The King of Macedon could not remain inactive; he assailed Athens with his navy and with some infantry. The Romans warned him, however, to withdraw or face war with Rome. After suffering a defeat at the hands of the Rhodian and Pergamese fleets, Philip withdrew, but not before attacking the city of Abydos on the Hellespont. Abydos fell after a long siege and most of its inhabitants committed suicide. Philip rejected the Roman ultimatum to stop attacking Greek states and the Romans declared war on Macedon. This left the Cretan cities with no major allies, and the largest city of Crete, Knossos, joined the Rhodians. Faced with this combination, both Hierapytna and Olous surrendered and were forced to sign a treaty favourable to Rhodes and Knossos.

Prelude

In 205 BC, the First Macedonian War came to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Phoenice, under the terms of which the Macedonians were not allowed to expand westwards. Rome, meanwhile, was preoccupied with Carthage, and Philip hoped to take advantage of this to seize control of the Greek world. He knew that his ambitions would be aided by an alliance with Crete and began pressing the Cretans to attack Rhodian assets.[1] Having crushed Pergamum, the dominant Greek state in Asia Minor, and formed an alliance with Aetolia, Philip was now opposed by no major Greek power other than Rhodes. Rhodes, an island state that dominated the south-eastern Mediterranean economically and militarily, was formally allied to Philip, but was also allied to his enemy Rome.[1] Furthermore, Philip worked towards consolidating his position as the major power in the Balkans. Marching his forces to Macedon's northern frontier, he inflicted a crushing defeat on the Illyrians, who lost 10,000 men in battle.[1] With his northern frontier secured, Philip was able to turn his attention towards the Aegean Sea.

Piracy and early campaigns

The Treaty of Phoenice prohibited Philip from expanding westward into Illyria or the Adriatic Sea, so the king turned his attentions eastwards to the Aegean Sea, where he started to build a large fleet.[2]

Philip saw two ways of shaking Rhodes' dominance of the sea: piracy and war. Deciding to use both methods, he encouraged his allies to begin pirate attacks against Rhodian ships. Philip convinced the Cretans, who had been involved in piracy for a long time, the Aetolians, and the Spartans to take part in the piracy. The lure for these nations was the promise of vast loot from captured Rhodian vessels.[3] He sent the Aetolian freebooter Dicaearchus on a large razzia through the Aegean, during the course of which he plundered the Cyclades and Rhodian territories.[2] Additionally, Philip sought to weaken the Rhodians' naval capacity through subterfuge. He achieved this by sending his agent, Heracleides, to Rhodes where he succeeded in burning 13 boat-sheds.[1]

By the end of 205 BC, Rhodes had been significantly weakened by these raids, and Philip saw his chance to go forward with the second part of his plan, direct military confrontation. He convinced the cities of Hierapytna and Olous and other cities in Eastern Crete to declare war against Rhodes.[3]

Rhodes' initial response to the declaration of war was diplomatic; they asked the Roman Republic for help against Philip. The Romans, however, were wary of another war, the Second Punic War having just ended. The Roman Senate attempted to persuade the populace to enter the war, even after Pergamum, Cyzicus and Byzantium had joined the war on the Rhodians side, but was unable to sway the city's war-weary population.[4]

At this point Philip further provoked Rhodes by attacking Cius, which was an Aetolian-allied city on the coast of the Sea of Marmara.[5] Despite attempts by Rhodes and other states to mediate a settlement, Philip captured and razed Cius as well as its neighbour Myrleia.[5] Philip then handed these cities over to his brother-in-law, the King of Bithynia, Prusias I who rebuilt and renamed the cities Prusa after himself and Apameia after his wife, respectively. In return for these cities Prusias promised that he would continue on expanding his kingdom at the expense of Pergamum (his latest war with Pergamum had ended in 205). The seizure of these cities also enraged the Aetolians, as both were members of the Aetolian League. The alliance between Aetolia and Macedon was held together only by the Aetolians' fear of Philip, and this incident worsened the already tenuous relationship.[6] Philip next compelled the cities of Lysimachia and Chalcedon, which were also members of the Aetolian League, to break off their alliance with Aetolia probably through the threatened use of violence.[7]

On the way home, Philip's fleet stopped at the island of Thasos off the coast of Thrace. Philip's general Metrodorus, went to the island's eponymous capital to meet emissaries from the city. The envoys said they would surrender the city to the Macedonians on the conditions that they not receive a garrison, that they not have to pay tribute or contribute soldiers to the Macedonian army and that they continue to use their own laws.[8] Metrodorus replied that the king accepted the terms, and the Thasians opened their gates to the Macedonians. Once within the walls, however, Philip ordered his soldiers to enslave all the citizens, who were then sold away, and to loot the city.[8] Philip's action during this campaign had a drastic impact on his reputation amongst the Greek states, where his actions were considered to be no better than the savage raids of the Aetolians and the Romans during the First Macedonian War.[5]

In 204 BC or the spring of 203 BC, Philip was approached by Sosibius and Agathocles of Egypt, the ministers of the young pharaoh Ptolemy V.[1] The ministers sought to arrange a marriage between Ptolemy and Philip's daughter in order to form an alliance against Antiochus III the Great, emperor of the Seleucid Empire, who was seeking to expand his empire at Egypt's expense. Philip, however, declined the proposal and in the winter of 203 BC-202 BC, Philip formed an alliance with Antiochus and organised the partition of the Ptolemaic Empire.[9] Philip agreed to help Antiochus to seize Egypt and Cyprus, while Antiochus promised to help Philip take control of Cyrene, the Cyclades and Ionia.[2]

In late 202 BC, the Aetolians sent ambassadors to Rome in order to form an alliance against Philip. Macedonian aggression had convinced the Aetolian League that they needed additional protectors in order to maintain their current position. However, the Romans rebuffed the Aetolian envoys as they were still seething about the fact that the Aetolians had come to terms with Philip to end the First Macedonian War. [5] The unsupportive attitude of Rome encouraged Philip to continue with his Aegean campaign. Philip considered control of the Aegean to be paramount in maintaining his regional dominance. By ruling the Aegean he would be able to isolate Pergamum as well as restrict Roman attempts to interfere in the Eastern Mediterranean.[5]

War against Pergamum and Rhodes

With the Seleucid treaty concluded, Philip's army attacked Ptolemy's territories in Thrace. Upon hearing that the King of Pergamum, Attalus I, had joined the Rhodian alliance, Philip became enraged and invaded Pergamese territory.[10] However, before having set out to campaign against Philip's navy in the Aegean Sea, Attalus had strengthened the city walls of his capital. By taking this and other precautions, he hoped to prevent Philip from a seizing a large amount of booty from his territory. Seeing that the city was undermanned, he sent his skirmishers against it, but they were easily repelled.[11] Judging that the city walls were too strong, Philip retreated after destroying a few temples, including the temple of Aphrodite and the sanctuary of Athena Nicephorus.[11] After the Macedonians captured Thyatira, they advanced to plunder the plain of Thebe, but the booty proved less fruitful than anticipated. Once he arrived at Thebe, he demanded supplies from the Seleucid governor of the region, Zeuxis. Zeuxis, however, never planned to give Philip substantial supplies.[11]

After withdrawing from Pergamese land, Philip with the Macedonian fleet headed south and after subduing the Cyclades, took the island of Samos from Ptolemy V, capturing the Egyptian fleet stationed there.[12] The fleet then turned north and laid siege to the island of Chios. Philip was planning to use the northern Aegean islands as stepping-stones as he worked his way down to Rhodes. The siege was not going well for Philip and the situation worsened as the combined fleets of Pergamum, Rhodes and their new allies, Kos, Cyzicus and Byzantium approached from both the north and south.[13] Philip, comprehending that the allies were attempting to seal his line of retreat, lifted the siege and began to sail for a friendly harbour.[14] However, he was confronted by the allied fleet, precipitating the Battle of Chios.

The Macedonian fleet of around 200 ships, manned by 30,000 men, significantly outnumbered the coalition's fleet of sixty-five large warships, nine medium vessels and three triremes.[5] The battle began with Attalus, who was commanding the allied left wing, advancing against the Macedonian right wing, while the allied right flank under the command of the Rhodian admiral Theophiliscus attacked the Macedonian's left wing. The allies gained the upper hand on their left flank and captured Philip's flagship; Philip's admiral, Democrates, was slain in the fighting.[15] Meanwhile, on the allied right flank, the Macedonians were initially successful in pushing the Rhodians back. Theophiliscus, fighting on his flagship, received three fatal wounds but managed to rally his men and defeat the Macedonian boarders. The Rhodians were able to use their superior navigational skills to incapacitate large numbers of Macedonian ships, swinging the battle back into their favour.[16]

On the allied left flank, Attalus saw one of his ships being sunk by the enemy and the one next to it in danger.[17] He decided to sail to the rescue with two quadriremes and his flagship. Philip, however, whose ship had not been involved in the fighting to this point, saw that Attalus had strayed some distance from his fleet and sailed to attack him with four quinqueremes and three hemioliae.[18] Attalus, seeing Philip approaching, fled in terror and was forced to run his ships aground. Upon landing he spread coins, purple robes and other splendid articles on the deck of his ship and fled to the city of Erythrae. When the Macedonians arrived at the shore, they stopped to collect the plunder. Philip, thinking that Attalus had perished in the chase, started towing away the Pergamese flagship.[18]

Following the flight of their monarch, the Pergamese fleet withdrew north. However, having been bested by the Rhodians on the allied right wing, the Macedonian left wing disengaged and retreated to join its victorious right flank. The withdrawal of the Macedonian left permitted the Rhodians to sail unmolested back into Chios' harbour.[18]

While the battle was not decisive, it was a significant setback for Philip, who lost 92 ships destroyed and 7 captured.[19] On the allied side, the Pergamese had three ships destroyed and two captured, while the Rhodians lost three ships sunk and none captured. During the battle the Macedonians lost 6,000 rowers and 3,000 marines killed and had 2,000 men captured. The casualties for the allies were significantly lower, with the Pergamese losing 70 men the Rhodians 60 killed, the allies as a whole losing 600 captured.[20] Peter Green describes this defeat as "crippling and costly", with Philip sustaining more casualties than he had previously suffered in any battle.[21]

After this battle, the Rhodian admirals decided to leave Chios and sail back home. On the way back to Rhodes, the Rhodian admiral Theophiliscus died of the wounds he received at Chios, but before he died he appointed Cleonaeus as his successor.[22] As the Rhodian fleet was sailing in the strait between Lade and Miletus on the shore of Asia Minor, Philip's fleet attacked them. Philip defeated the Rhodian fleet in the Battle of Lade and forced it to retreat back to Rhodes.[23] The Milesians were impressed by the victory and sent Philip and Heracleides garlands of victory when they entered Milesian territory as did the city of Hiera Cone.[24]

Asia Minor campaign

Philip, disappointed by the spoils in Mysia, proceeded south and plundered the towns and cities of Caria. He invested Prinassus, which held out bravely at first, but when Philip set up his artillery, he sent an envoy into the city offering to let them leave the city unharmed or they would all be killed. The citizens decided to abandon the city.[25] At this stage in the campaign, Philip's army was running out of food, so he seized the city of Myus and gave it to the Magnesians in return for food supplies. Since the Magnesians had no grain, Philip settled for enough figs to feed his whole army.[26] Subsequently, Philip turned north in order to seize and garrison the cities of Iasos, Bargylia, Euromus and Pedasa in quick succession.[27]

While Philip's fleet was wintering in Bargylia, the combined Pergamese and Rhodian fleet blockaded the harbour. The situation in the Macedonian camp became so grave that the Macedonians were close to surrendering.[21] The dire situation was alleviated somewhat by supplies sent by Zeuxis.[28] Philip, however, managed to get out by trickery. He sent an Egyptian deserter to Attalus and the Rhodians to say that he was preparing to attack the allies the next day. Upon hearing the news, Attalus and the Rhodians started preparing the fleet for the oncoming attack.[21] While the allies were making their preparations, Philip slipped past them by night with his fleet, leaving numerous campfires burning to give the appearance that he remained in his camp.[21]

While Philip was involved in this campaign, his allies the Acarnanians became involved in a war against Athens after the Athenians murdered two Acarnanian athletes.[29] The Acarnanians complained to Philip about this provocation, and he decided to send a force under the command of Nicanor the Elephant to assist them in their attack on Attica.[30] The Macedonians and their allies plundered and looted Attica before attacking Athens.[31] The invaders made it as far as the Academy of Athens when the Roman ambassadors in the city ordered the Macedonians to retreat or to face war with Rome.[30]

Philip's fleet had just escaped from the allied blockade and Philip ordered that a squadron head to Athens. The Macedonian squadron sailed into Piraeus and captured four Athenian ships.[30] As the Macedonian squadron was retreating, the Rhodian and Pergamese fleet, which had followed Philip's ships across the Aegean, appeared from the allied base at Aegina and attacked the Macedonians. The allies defeated the Macedonian fleet and recaptured the Athenian ships, which they returned to the Athenians.[21] The Athenians were so pleased by the rescue that they replaced the recently abolished pro-Macedonian tribes, the Demetrias and Antigonis tribes, with the Attalid tribe in honour of Attalus as well as destroying monuments that had previously been erected in honour of Macedonian Kings.[32] Attalus and the Rhodians convinced the Athenian assembly to declare war on the Macedonians.[33]

The Pergamese fleet sailed back to their base at Aegina and the Rhodians set out to conquer all the Macedonian islands from Aegina to Rhodes, successfully assaulting all except Andros, Paros and Cythnos.[34] Philip ordered his prefect on the island of Euboea, Philoces, to assault Athens once again with 2,000 infantry and 200 cavalry. Philocles was unable to capture Athens, but ravaged the surrounding countryside.[34]

Roman intervention

Meanwhile, Rhodian, Pergamese, Egyptian, anti-Macedonian Cretan and Athenian delegations travelled to Rome to appear before the Senate.[35] When they were given audience they informed the Senate about the treaty between Philip and Antiochus and complained of Philip's attacks on their territories. In response to these complaints the Romans sent three ambassadors, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Gaius Claudius Nero and Publius Sempronius Tuditanus to Egypt with the orders to go to Rhodes after speaking with Ptolemy.[36]

While this was happening, Philip attacked and occupied the cities in Thrace which still belonged to Ptolemy, Maroneia, Cypsela, Doriscos, Serrheum and Aemus. The Macedonians then advanced on the Thracian Chersonese where they captured the cities of Perinthus, Sestos, Elaeus, Alopeconnesus, Callipolis and Madytus.[37] Philip then descended to the city of Abydos, which was held by a combined Pergamese and Rhodian garrison. Philip started the siege by blockading the city by land and sea to stop attempts to reinforce or supply the city. The Abydenians, full of confidence, dislodged some of the siege engines with their own catapults while some of Philip's other engines were burnt by the defenders. With their siege weaponry in tatters, the Macedonians started undermining the city's walls, eventually succeeding in collapsing the outer wall.[38]

The situation was now grave for the defenders and they decided to send two of their most prominent citizens to Philip as negotiators. Appearing before Philip, these men offered to surrender the city to him on the conditions that the Rhodian and the Pergamese garrisons were allowed to leave the city under a truce and that all the citizens were permitted to leave the city with the clothes they were wearing and go wherever they pleased, in effect meaning an unconditional surrender.[39] Philip replied that they should "surrender at discretion or fight like men."[40] The ambassadors, powerless to do more, carried this response back to the city.'[40]

Informed of this response, the city's leaders called an assembly to determine their course of action. They decided to liberate all slaves to secure their loyalty, to place all the children and their nurses in the gymnasium and to put all the women in the temple of Artemis. They also asked for everyone to bring forward their gold and silver and any clothes that were valuable so they could put them in the boats of the Rhodians and the Cyzicenes.[41] Fifty elder and trusted men were elected to carry out these tasks. All the citizens then swore an oath. As Polybius writes:

| “ | ... whenever they saw the inner wall being captured by the enemy, they would kill the children and women, and would burn the above mentioned ships, and, in accordance with the curses that had been invoked, would throw the silver and gold into the sea.[41] | ” |

After reciting the oath, they brought forward the priests and everyone swore that they would defeat the enemy or die trying.'[41]

When the interior wall fell, the men, true to their promise, sprang from the ruins and fought with great courage, forcing Philip to send his troops forward in relays to the front line. By nightfall the Macedonians retreated to camp. That night the Abydenians resolved to save the women and children and at daybreak they sent some priests and priestess with a garland across to the Macedonians, surrendering the city to Philip.[42]

Meanwhile, Attalus sailed across the Aegean to the island of Tenedos. The youngest of the Roman ambassadors, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, had heard about the siege at Abydos while he was in Rhodes and he arrived at Abydos to find Philip. Meeting the king outside the city, Lepidus informed him of the Senate's wishes.[43] Polybius writes:

| “ | The Senate had resolved to order him not to wage war with any Greek state; nor to interfere in the dominions of Ptolemy; and to submit the injuries inflicted on Attalus and the Rhodians to arbitration; and that if he did so he might have peace, but if he refused to obey he would promptly have war with Rome." Upon Philip endeavoring to show that the Rhodians had been the first to lay hands on him, Marcus interrupted him by saying: "But what about the Athenians? And what about the Cianians? And what about the Abydenians at this moment? Did any one of them also lay hands on you first?" The king, at a loss for a reply, said: "I pardon the offensive haughtiness of your manners for three reasons: first, because you are a young man and inexperienced in affairs; secondly, because you are the handsomest man of your time" (this was true); "and thirdly, because you are a Roman. But for my part, my first demand to the Romans is that they should not break their treaties or go to war with me; but if they do, I shall defend myself as courageously as I can, appealing to the gods to defend my cause.[44] | ” |

While Philip was walking through Abydos, he saw people killing themselves and their families by stabbing, burning, hanging, and jumping down wells and from rooftops. Philip was surprised to see this, and published a proclamation announcing that would give three day's grace to anybody wishing to commit suicide.[45] The Abydenians, who were bent on following the orders of the original decree, thought that this would amount to treason to the people who had already died, and refused to live under these terms. Apart from those in chains or similar restraints, each family individually hurried to their deaths.[44]

Philip then ordered another attack on Athens; his army failed to take either Athens or Eleusis, but subjected Attica to the worst ravaging the Atticans had seen since the Persian Wars.[46] In response, the Romans declared war on Philip and invaded his territories in Illyria. Philip was forced to abandon his Rhodian and Pergamese campaign in order to deal with the Romans and the situation in Greece. Thus began the Second Macedonian War.[47]

After Philip's withdrawal from his campaign against Rhodes, the Rhodians were free to attack Olous and Hierapytna and their other Cretan allies. Rhodes' search for allies in Crete bore fruit when the Cretan city of Knossos saw that the war was going in Rhodes' favour and decided to join Rhodes in an attempt to gain supremacy over the island.[3] Many other cities in central Crete subsequently joined Rhodes and Knossos against Hierapytna and Olous. Now under attack on two fronts, Hierapytna surrendered.[3]

Aftermath

Under the treaty signed at the conclusion of the war, Hierapytna agreed to break off all relations and alliances with foreign powers and to place all its harbors and bases at Rhodes' disposal. Olous, among the ruins of which the terms of the treaty have been found, had to accept Rhodian domination.[3] As a result, Rhodes was left with control of a significant part of eastern Crete after the war. The conclusion of the war left the Rhodians free to help their allies in the Second Macedonian War.

The war had no particular short-term effect on the rest of Crete. Pirates and mercenaries there continued in their old occupations after the war's end. In the Battle of Cynoscephalae during the Second Macedonian War three years later, Cretan mercenary archers fought for both the Romans and the Macedonians.[48]

The war was costly for Philip and the Macedonians, losing them a fleet that had taken three years to build as well as triggering the defection of their Greek allies, the Achean League and the Aetolian League, to the Romans. In the war's immediate aftermath the Dardani, a barbarian tribe, swarmed across the northern border of Macedon, but Philip was able to repel this attack.[46] In 197, however, Philip was defeated in the Battle of Cynoscephalae by the Romans and was forced to surrender.[49] This defeat cost Philip most of his territory outside Macedon and he had to pay a war indemnity of 1,000 talents of silver to the Romans.[50]

The Rhodians regained control over the Cyclades and reconfirmed their naval supremacy over the Aegean. The Rhodians' possession of eastern Crete allowed them to largely stamp out piracy in that area, but pirate attacks on Rhodian shipping continued and eventually led to the Second Cretan War.[3] Attalus died in 197 and was succeeded by his son, Eumenes II, who continued his father's anti-Macedonian policy. The Pergamese, meanwhile, came out of the war having gained several Aegean islands which had been in Philip's possession and went on to become the supreme power in Asia Minor, rivaled only by Antiochus.[30]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hammond 1988, p. 411.

- 1 2 3 Green 1993, p. 305.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Detorakis 1994.

- ↑ Matyszak 2004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hammond 1988, p. 413.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 15.23.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 15.23; Hammond 1988, p. 413.

- 1 2 Polybius & Walbank 1979, 15.24; Hammond 1988, p. 413.

- ↑ Hammond 1988, p. 412.

- ↑ Errington 1990, p. 197.

- 1 2 3 Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.1.

- ↑ Green 1993, p. 306; Hammond 1988, p. 414.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.2; Hammond 1988, p. 414; Walbank 1967, p. 201.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.2; Hammond 1988, p. 414.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.2; Walbank 1967, p. 122.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.2; Walbank 1967, p. 123.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.6; Walbank 1967, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.6; Hammond 1988, p. 415.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.7; Hammond 1988, p. 415.

- ↑ Walbank 1967, p. 124; Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Green 1993, p. 306.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.9.

- ↑ Errington 1990, p. 198.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.2; Hammond 1988, p. 416.

- ↑ Walbank 1967, p. 124; Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.27.

- ↑ Walbank 1967, p. 124; Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.24.

- ↑ Hammond 1988, p. 416.

- ↑ Hammond 1988, p. 417.

- ↑ Livy & Bettison 1976, 31.14; Errington 1990, p. 201.

- 1 2 3 4 Green 1993, p. 307.

- ↑ Livy & Bettison 1976, 31.14; Green 1993, p. 307.

- ↑ Green 1993, pp. 306-7; Errington 1990, p. 201.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.26; Green 1993, p. 307.

- 1 2 Livy & Bettison 1976, 31.15; Green 1993, p. 307.

- ↑ Errington 1990, p. 201.

- ↑ Livy & Bettison 1976, 31.15; Hammond 1988, p. 418.

- ↑ Livy & Bettison 1976, 31.16; Hammond 1988, p. 418.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.30; Hammond 1988, p. 418.

- ↑ Walbank 1967, p. 134; Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.30.

- 1 2 Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.30.

- 1 2 3 Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.31.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.33; Hammond 1988, p. 418.

- ↑ Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.34; Hammond 1988, p. 419.

- 1 2 Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.34.

- ↑ Walbank 1967, p. 134; Polybius & Walbank 1979, 16.34.

- 1 2 Green 1993, p. 309.

- ↑ Walbank 1967, p. 135.

- ↑ Livy & Bettison 1976, 33.4-5; Walbank 1967, pp. 167-8.

- ↑ Livy & Bettison 1976, 33.11; Fox 2006, p. 327.

- ↑ Livy & Bettison 1976, 33.30; Green 1993, p. 309.

Sources

Ancient sources

- Livy; Bettison, Henry (translator) (1976). Rome and the Mediterranean. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044362-2.

- Polybius; Walbank, Frank W. (translator) (1979). The Rise of the Roman Empire. New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044318-9.

Modern sources

- Detorakis, Theocharis (1994). A History of Crete. Heraklion: Iraklion. ISBN 978-960-220-712-3.

- Errington, Robert Malcolm (1990). A History of Macedonia. United States of America: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520063198.

- Fox, Robert Lane (2006). The Classical World. United Kingdom: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-103761-5.

- Green, Peter (1993). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. United States of America: University of California Press. ISBN 0-500-01485-X.

- Hammond, N. G. L. (1988). A History of Macedonia: 336–167 BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198148151.

- Matyszak, Philip (2004). The Enemies of Rome:From Hannibal to Attila. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-25124-9.

- Walbank, F. W. (1967). Philip V of Macedon. United Kingdom: Archon Books. OCLC 601891051.