Big Thicket

| Big Thicket National Preserve | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

| |

| |

| Location | Southeast Texas, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Kountze, Texas |

| Coordinates | 30°32′48″N 94°20′25″W / 30.54667°N 94.34028°WCoordinates: 30°32′48″N 94°20′25″W / 30.54667°N 94.34028°W |

| Area | 112,501 acres (45,528 ha)[1] |

| Authorized | October 11, 1974 |

| Visitors | 137,722 (in 2011)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Big Thicket National Preserve |

Big Thicket is the name of a heavily forested area in Southeast Texas, United States. Several attempts to provide boundaries have been made ranging from only a 10 to 15 mile section of Hardin County to an area encompassing over 29 counties and over 3,350,000 acres. Scientific studies have been performed also, but with varying results. In "... 1936, ... Hal B. Parks and Victor L. Cory of the Texas Agriculture Experiment station conducted a biological survey of the Big Thicket region". Their study, based on geology, resulted in over 3,350,000 acres of Southeast Texas and covering 14 counties from Houston in the west to Orange in the east and Huntsville to Wiergate on the north. Claude McLeod, a botany professor at Sam Houston State University, performed a botanical based study. That study resulted in a region of over 2,000,000 acres.[3] While no exact boundaries exist, the area occupies much of Hardin, Liberty, Tyler, San Jacinto, and Polk Counties and is roughly bounded by the San Jacinto River, Neches River, and Pine Island Bayou. To the north, it blends into the larger Piney Woods terrestrial ecoregion of which it is a part. It has historically been the most dense forest region in what is now Texas, though logging in the 19th and 20th centuries dramatically reduced the forest concentration.

The Big Thicket has been described as one of the most biodiverse areas in the world outside of the tropics. The Big Thicket National Preserve (BITH) was established in 1974 in an attempt to protect the many plant and animal species within. BITH, along with Big Cypress National Preserve in Florida, became the first national preserves in the United States National Park System when both were authorized by the United States Congress on October 11, 1974. Senator Ralph Yarborough was its most powerful proponent in Congress and the bill was proposed by Charles Wilson and Bob Eckhardt that established the 84,550-acre Preserve.[4] Big Thicket was also designated as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO in 1981. As of September 30, 2016, the preserve includes 112,501 acres.[1] It consists of nine separate land units as well as six water corridors. Centered about Hardin County, Texas, the BITH extends into parts of surrounding Jasper, Jefferson, Liberty, Orange, Polk, and Tyler counties.[5]

The Preserve's headquarters are located 8 miles north of Kountze, Texas and approximately 30 miles north of Beaumont via US 69/287.

Geography

- One's fondness for the area is hard to explain. It has no commanding peak or awesome gorge, no topographical feature of distinction. Its appeal is more subtle. – Big Thicket Legacy, University of Texas Press, 1977.

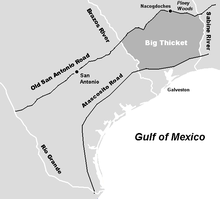

The terrain in the Big Thicket is flat or gently rolling. The area lies on the flat coastal plain of Texas, and is crossed by numerous small streams. The extent of the region was once much larger than today covering more than 2 million acres (8,100 km2) in east Texas.[6] The Spaniards, who once ruled the region, defined its boundaries in the north as El Camino Real de los Tejas, a trail that ran from central Texas to Nacogdoches; in the south as La Bahia Road or Atascosito Road, a trail that ran from southwest Louisiana into southeast Texas west of Galveston Bay; to the west by the Brazos River; and to the east by the Sabine River.[4] Timber harvesting in the 19th and 20th centuries dramatically reduced the extent of the dense woodlands. Prior to the acquisition of a reservation in 1854, the Alabama-Coushattas resided in the Big Thicket.[7]

The Big Thicket's geographical features are believed to have their origins with the Western Interior Seaway, an inland sea that covered much of North America during the Cretaceous period. Over time, water smoothed out the land along what is now Texas's coastline.

Small towns are contained within the Big Thicket. Most of these towns developed in the late 19th century in support of the lumber industry, as evidenced by names like Lumberton. As transportation through the area improved (including the construction of US 59, US 69 and 96), many of the towns slowly became suburbs of the much larger cities of Beaumont to the south and Houston to the southwest.

Biology

What the Big Thicket lacks in geographical aesthetics is made up for by the biodiversity contained within. During the last glacial period, plant and animal species from many different biomes moved into the area. Before their extinction, the Big Thicket was home to most species of North American megafauna.

Today the Big Thicket retains numerous species, and has been described as the "biological crossroads of North America" or the "American Ark". The area contains over 100 species of trees and shrubs, with Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) once dominating the region. Big Thicket National Preserve has introduced programs to re-establish this dominance, including one of the US's most active prescribed burn programs. With the National Park Service's centennial occurring in 2016, efforts are in progress to plant between 100,000 and 300,000 Longleaf Pines. The National Park Service lists more than one thousand species of flowering plants and ferns that can also be found in the thicket, including 20 orchids and four types of carnivorous plants.

Animal life includes 300 species of migratory and nesting birds, many endangered or threatened including the Red-cockaded Woodpecker, and possibly extinct Ivory-billed Woodpecker.[8] The thicket is also home to numerous reptile species, including all four groups of North American venomous snakes and alligators.

Ghost Road

A dirt road leading north out of the town of Saratoga is the core of the area's predominant ghost story. Bragg Road, as it is more formally known, was constructed in 1934 on the bed of a former railroad line that had serviced the lumber industry.

In the 1940s, stories began to circulate about a mysterious light, sometimes referred to as the Light of Saratoga, that could be seen on and near the road at night. No adequate explanation of the light has been offered. The various ghost stories include reference to the Kaiser Burnout, long-dead conquistadors looking for their buried treasure, a decapitated railroad worker, and a lost night hunter eternally searching for a way out.

Less paranormal explanations include swamp gas, and automobile headlights filtering through the trees.

See also

- History of Texas forests

- Defining the Big Thicket: Prelude to Preservation

- Cozine, James (2004). Saving the Big Thicket: from exploration to preservation, 1685-2003. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas. ISBN 1-57441-175-6.

References

- 1 2 "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2014". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ James J., Cozine, Jr. (2004). Saving the Big Thicket From Exploration to Preservation, 1685-2003. University of North Texas Press. p. 4. ISBN 1-57441-175-6. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- 1 2 Abernethy, Francis E.: Big Thicket from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 24 Aug, 2012. Texas State Historical Association

- ↑ "Big Thicket National Preserve Texas" (pdf). National Park Service U.S. Department of Interior. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ↑ Cozine (2004) p. x.

- ↑ Hudson, Charles M. (1976). The Southeastern Indians. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press. p. 492. ISBN 0-87049-248-9.

- ↑ Michael Graczyk (February 21, 2007). "Big Thicket searches seek giant woodpecker that might be extinct". USA Today. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Big Thicket. |

- Big Thicket National Preserve

- Big Thicket in the Handbook of Texas

- Biosphere Reserve Information for the Big Thicket

- Bragg Road - The Ghost Road of Hardin County

- Fun365Days.com -- regional tourism web site

- Big Thicket Association