Armies in the American Civil War

This article is designed to give background into the organization and tactics of Civil War armies. This brief survey is by no means exhaustive, but it should give enough material to have a better understanding of the capabilities of the forces that fought the American Civil War. Understanding these capabilities should give insight into the reasoning behind the decisions made by commanders on both sides.[1]

.jpg)

Organization

The US Army in 1861

The Regular Army of the United States on the eve of the Civil War was essentially a frontier constabulary whose 16,000 officers and men were organized into 198 companies scattered across the nation at 79 different posts. In 1861, this Army was under the command of Brevet Lieutenant General Winfild Scott, the 75‑year‑old hero of the Mexican‑American War. His position as general in chief was traditional, not statutory, because secretaries of war since 1821 had designated a general to be in charge of the field forces without formal congressional approval. During the course of the war, Lincoln would appoint other generals in chief with little success until finally appointing Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant to the position prior to the Overland Campaign. The field forces were controlled through a series of geographic departments whose commanders reported directly to the general in chief. This department system, frequently modified, would be used by both sides throughout the Civil War for administering regions under Army control. Army administration was handled by a system of bureaus whose senior officers were, by 1860, in the twilight of long careers in their technical fields. Six of the 10 bureau chiefs were over 70 years old. These bureaus, modeled after the British system, answered directly to the War Department and were not subject to the orders of the general in chief. The bureaus reflected many of today’s combat support and combat service support branches; however, there was no operational planning or intelligence staff. American commanders before the Civil War had never required such a structure.[2] This system provided suitable civilian control and administrative support to the small field army prior to 1861. Ultimately, the bureau system would respond sufficiently, if not always efficiently, to the mass mobilization required over the next four years. Indeed, it would remain essentially intact until the early 20th century. The Confederate government, forced to create an army and support organization from scratch, established a parallel structure to that of the US Army. In fact, many important figures in Confederate bureaus had served in the prewar Federal bureaus.[3]

| Quartermaster | Medical |

| Ordnance | Adjutant General |

| Subsistence | Paymaster |

| Engineer | Inspector General |

| Topographic Engineer* | Judge Advocate General |

| *(Merged with the Engineer Bureau in 1863.) | |

Raising the Armies

With the outbreak of war in April 1861, both sides faced the monumental task of organizing and equipping armies that far exceeded the prewar structure in size and complexity. The Federals maintained control of the Regular Army, and the Confederates initially created a Regular force, though in reality it was mostly on paper. Almost immediately, the North lost many of its officers to the South, including some of exceptional quality. Of 1,108 Regular Army officers serving as of 1 January 1861, 270 ultimately resigned to join the South. Only a few hundred of 15,135 enlisted men, however, left the ranks.

The federal government had two basic options for the use of the Regular Army. The government could divide the Regulars into training and leadership cadre for newly formed volunteer regiments or retain them in “pure” units to provide a reliable nucleus for the Federal Army in coming battles.

For the most part, the government opted to keep the Regulars together. During the course of the war, battle losses and disease thinned the ranks of Regulars, and officials could never recruit sufficient replacements in the face of stiff competition from the states that were forming volunteer regiments. By November 1864, many Regular units had been so depleted that they were withdrawn from front-line service, although some Regular regiments fought with the Army of the Potomac in the Overland Campaign. In any case, the war was fought primarily with volunteer officers and men, the vast majority who started the war with no previous military training or experience. However, by 1864, both the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia were largely experienced forces that made up for a lack of formal training with three years of hard combat experience. Neither side had difficulty in recruiting the numbers initially required to fill the expanding ranks. In April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 men from the states’ militias for a three‑month period.

This figure probably represented Lincoln’s informed guess as to how many troops would be needed to quell the rebellion quickly. Almost 92,000 men responded, as the states recruited their “organized” but untrained militia companies. At the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, these ill‑trained and poorly equipped soldiers generally fought much better than they were led. Later, as the war began to require more manpower, the federal government set enlistment quotas through various “calls,” which local districts struggled to fill. Similarly, the Confederate Congress authorized the acceptance of 100,000 one‑year volunteers in March 1861. One‑third of these men were under arms within a month. The Southern spirit of voluntarism was so strong that possibly twice that number could have been enlisted, but sufficient arms and equipment were not then available.

As the war continued and casualty lists grew, the glory of volunteering faded, and both sides ultimately resorted to conscription to help fill the ranks. The Confederates enacted the first conscription law in American history in April 1862, followed by the federal government’s own law in March 1863. Throughout these first experiments in American conscription, both sides administered the programs in less than a fair and efficient way. Conscription laws tended to exempt wealthier citizens, and initially, draftees could hire substitutes or pay commutation fees. As a result, the average conscript maintained poor health, capability, and morale. Many eligible men, particularly in the South, enlisted to avoid the onus of being considered a conscript. Still, conscription or the threat of conscription ultimately helped provide a large quantity of soldiers.

Conscription was never a popular program, and the North, in particular, tried several approaches to limit conscription requirements. These efforts included offering lucrative bounties, fees paid to induce volunteers to fill required quotas. In addition, the Federals offered a series of reenlistment bonuses, including money, 30‑day furloughs, and the opportunity for veteran regiments to maintain their colors and be designated as “veteran” volunteer infantry regiments. The Federals also created an Invalid Corps (later renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps) of men unfit for front‑line service who performed essential rear area duties. In addition, the Union recruited almost 179,000 African-Americans, mostly in federally organized volunteer regiments. In the South, recruiting or conscripting slaves was so politically sensitive that it was not attempted until March 1865, far too late to influence the war.

Whatever the faults of the manpower mobilization, it was an impressive achievement, particularly as a first effort on that scale. Various enlistment figures exist, but the best estimates are that approximately two million men enlisted in the Federal Army from 1861 to 1865. Of that number, one million were under arms at the end of the war. Because the Confederate records are incomplete or lost, estimates of their enlistments vary from 600,000 to over 1.5 million. Most likely, between 750,000 and 800,000 men served the Confederacy during the war, with peak strength never exceeding 460,000 men.[4]

The unit structure into which the expanding armies were organized was generally the same for Federals and Confederates, reflecting the common roots of both armies. The Federals began the war with a Regular Army organized into an essentially Napoleonic, musket-equipped structure. Both sides used a variant of the old Regular Army structure for newly formed volunteer regiments. The Federal War Department established a volunteer infantry regimental organization with a strength that could range from 866 to 1,046 (varying in authorized strength by up to 180 infantry privates). The Confederate Congress field its 10‑company infantry regiment at 1,045 men. Combat strength in battle, however, was always much lower (especially by the time of the Overland Campaign) because of casualties, sickness, leaves, details, desertions, and straggling.

The battery remained the basic artillery unit, although battalion and larger formal groupings of artillery emerged later in the war in the eastern theater. Four under strength Regular artillery regiments existed in the US Army at the start of the war and one Regular regiment was added in 1861, for a total of 60 batteries. Nevertheless, most batteries were volunteer organizations. For the first years of the war and part way into the Overland Campaign, a Federal battery usually consisted of six guns and had an authorized strength of 80 to 156 men. A battery of six 12‑pound Napoleons could include 130 horses. If organized as “horse” or fling artillery, cannoneers were provided individual mounts, and more horses than men could be assigned to the battery. After the battle of Spotsylvania in 1864, most of the Army of the Potomac’s artillery was reorganized into four-gun batteries. Their Confederate counterparts, plagued by limited ordnance and available manpower, usually operated throughout the war with a four-gun battery, often with guns of mixed types and calibers. Confederate batteries seldom reached their initially authorized manning level of 80 soldiers.

Prewar Federal mounted units were organized into five Regular regiments (two dragoon, two cavalry, and one mounted rifle), and one Regular cavalry regiment was added in May 1861. Although the term “troop” was officially introduced in 1862, most cavalrymen continued to use the more familiar term “company” to describe their units throughout the war. The Federals grouped two companies or troops into squadrons, with four to six squadrons comprising a regiment. Confederate cavalry units, organized in the prewar model, were authorized 10 76-man companies per regiment.[5] Some volunteer cavalry units on both sides also formed into smaller cavalry battalions. Later in the war, both sides began to merge their cavalry regiments and brigades into division and corps organizations.

For both sides, the infantry unit structure above regimental level was similar to today’s structure, with a brigade controlling three to five regiments and a division controlling two or more brigades. Federal brigades generally contained regiments from more than one state, while Confederate brigades often consisted of regiments from the same state. In the Confederate Army, a brigadier general usually commanded a brigade, and a major general commanded a division. The Federal Army, with no rank higher than major general until 1864, often had colonels commanding brigades, brigadier generals commanding divisions, and major generals commanding corps and armies. Grant received the revived rank of lieutenant general in 1864, placing him with clear authority over all of the Federal armies, but rank squabbles between the major generals appeared within the Union command structure throughout the Overland Campaign.

The large numbers of organizations formed, are a reflection of the politics of the time. The War Department in 1861 considered making recruitment a Federal responsibility, but this proposal seemed to be an unnecessary expense for the short war initially envisioned. Therefore, the responsibility for recruiting remained with the states, and on both sides state governors continually encouraged local constituents to form new volunteer regiments. This practice served to strengthen support for local, state, and national politicians and provided an opportunity for glory and high rank for ambitious men. Although such local recruiting created regiments with strong bonds among the men, it also hindered filing the ranks of existing regiments with new replacements. As the war progressed, the Confederates attempted to funnel replacements into units from their same state or region, but the Federals continued to create new regiments. Existing Federal regiments detailed men back home to recruit replacements, but these efforts could never successfully compete for men joining new local regiments. The newly formed regiments thus had no seasoned veterans to train the recruits, and the battle-tested regiments lost men faster than they could recruit replacements. Many regiments on both sides (particularly for the North) were reduced to combat ineffectiveness as the war progressed. Seasoned regiments were often disbanded or consolidated, usually against the wishes of the men assigned.[6]

| Federal | Confederate | |

| Infantry | 19 Regular Regiments | 642 Regiments |

| 2,125 Volunteer Regiments | 9 Legions" | |

| 60 Volunteer Battalions | 163 Separate Battalions | |

| 351 Separate Companies | 62 Separate Companies | |

| Artillery | 5 Regular Regiments | 16 Regiments |

| 61 Volunteer Regiments | 25 Battalions | |

| 17 Volunteer Battalions | 227 Batteries | |

| 408 Separate Batteries | ||

| Cavalry | 6 Regular Regiments | 137 Regiments |

| 266 Volunteer Regiments | 1 Legion* | |

| 45 Battalions | 143 Separate Battalions | |

| 78 Separate Companies | 101 Separate Companies | |

| *Legions were a form of combined arms team, with artillery , cavalry, and infantry. They were approximately the strength of a large regiment. Long before the end of the war, legions lost their combined arms organisation. | ||

The infantry regiment was the basic administrative and tactical unit of the Civil War armies. Regimental headquarters consisted of a colonel, lieutenant colonel, major, adjutant, quartermaster, surgeon (with rank of major), two assistant surgeons, a chaplain, sergeant major, quartermaster sergeant, commissary sergeant, hospital steward, and two principal musicians. Each regiment was staffed by a captain, a first lieutenant, a second lieutenant, a first sergeant, four sergeants, eight corporals, two musicians, and one wagoner. The authorized strength of a Civil War infantry regiment was about 1,000 officers and men, arranged in ten companies plus a headquarters and (for the first half of the war at least) a band. Discharges for physical disability, disease, special assignments (bakers, hospital nurses, or wagoners), court martial, and battle injuries all combined to reduce effective combat strength. Before too long a typical regiment might be reduced to less than 500. Brigades were made up of two or more regiments, with four regiments being most common. Union brigades averaged 1,000 to 1,500 men, while on the Confederate side they averaged 1,500 to 1,800. Union brigades were designated by a number within their division, and each Confederate brigade was designated by the name of its current or former commander.

Divisions were formed of two or more brigades. Union divisions contained 2,500 to 4,000 men, while the Confederate division was somewhat larger, containing 5,000 to 6,000 men. As with brigades, Union divisions were designated by a number in the Corps, while each Confederate division took the name of its current or former commander. Corps were formed of two or more divisions. The strength of a Union corps averaged 9,000 to 12,000 officers and men, those of Confederate armies might average 20,000. Two or more corps usually constituted an army, the largest operational organization. During the Civil War there were at least 16 armies on the Union side, and 23 on the Confederate side . In the Eastern Theater the two principal adversaries were the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. There were generally seven corps in the Union Army of the Potomac, although by the spring of 1864 the number was reduced to four. From the Peninsula campaign through the Battle of Antietam the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was organized into Longstreet's and Jackson's "commands," of about 20,000 men each. In November 1862 the Confederate Congress officially designated these commands as corps. After Jackson's death in May 1863 his corps was divided in two, and thereafter the Army of Northern Virginia consisted of three corps.[7]

The Leaders

Because the organization, equipment, tactics, and training of the Confederate and Federal armies were similar, the performance of units in battle often depended on the quality and performance of their individual leaders. Both sides sought ways to find this leadership for their armies. The respective central governments appointed the general officers. At the start of the war, most, but certainly not all, of the more senior officers had West Point or other military school experience. In 1861, Lincoln appointed 126 general officers, of which 82 were or had been professionally trained officers. Jefferson Davis appointed 89, of which 44 had received professional training. The rest were political appointees, but of these only 16 Federal and 7 Confederate generals lacked military experience. Of the lower ranking volunteer officers who comprised the bulk of the leadership for both armies, state governors normally appointed colonels (regimental commanders). States also appointed other field grade officers, although many were initially elected within their units. Company grade officers were usually elected by their men. This long‑established militia tradition, which seldom made military leadership and capability a primary consideration, was largely an extension of states’ rights and sustained political patronage in both the Union and the Confederacy. Much has been made of the West Point backgrounds of the men who ultimately dominated the senior leadership positions of both armies, but the graduates of military colleges were not prepared by such institutions to command divisions, corps, or armies. Moreover, though many leaders had some combat experience from the Mexican War era, very few had experience above the company or battery level in the peacetime years prior to 1861. As a result, the war was not initially conducted at any level by “professional officers” in today’s terminology. Leaders became more professional through experience and at the cost of thousands of lives. General William T. Sherman would later note that the war did not enter its “professional stage” until 1863. By the time of the Overland Campaign, many officers, though varying in skill, were at least comfortable at commanding their formations.[8]

Civil War Staffs

In the Civil War, as today, the success of large military organizations and their commanders often depended on the effectiveness of the commanders’ staffs. Modern staff procedures have evolved only gradually with the increasing complexity of military operations. This evolution was far from complete in 1861, and throughout the war, commanders personally handled many vital staff functions, most notably operations and intelligence. The nature of American warfare up to the mid-19th century did not seem to overwhelm the capabilities of single commanders. However, as the Civil War progressed the armies grew larger and the war effort became a more complex undertaking and demanded larger staffs. Both sides only partially adjusted to the new demands, and bad staff work hindered operations for both the Union and Confederate forces in the Overland Campaign. Civil War staffs were divided into a “general staff” and a “staff corps.” This terminology, defined by Winfield Scott in 1855, differs from modern definitions of the terms. Except for the chief of staff and aides-de-camp, who were considered personal staff and would often depart when a commander was reassigned, staffs mainly contained representatives of the various bureaus, with logistical areas being best represented. Later in the war, some truly effective staffs began to emerge, but this was the result of the increased experience of the officers serving in those positions rather than a comprehensive development of standard staff procedures or guidelines. Major General George B. McClellan, when he appointed his father‑in‑law, was the first to officially use the title “chief of staff.” Even though many senior commanders had a chief of staff, this position was not used in any uniform way and seldom did the man in this role achieve the central coordinating authority of the chief of staff in a modern headquarters. This position, along with most other staff positions, was used as an individual commander saw fit, making staff responsibilities somewhat different under each commander. This inadequate use of the chief of staff was among the most important shortcomings of staffs during the Civil War. An equally important weakness was the lack of any formal operations or intelligence staff. Liaison procedures were also ill defined, and various staff officers or soldiers performed this function with little formal guidance. Miscommunication or lack of knowledge of friendly units proved disastrous time after time in the war’s campaigns.[9]

| General Staff |

|---|

| Chief of staff Aides |

| Assistant adjutant general |

| Assistant inspector general |

| Staff Corps |

| Engineer |

| Ordnance |

| Quartermaster |

| Subsistence |

| Medical |

| Pay |

| Signal |

| Provost marshal |

| Chief of artillery |

The Armies at Vicksburg

Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee was organized into four infantry corps. Major General Stephen A. Hurlbut's XVI Corps, however, remained headquartered in Memphis performing rear-area missions throughout the campaign, although nearly two divisions did join Grant during the siege. The remaining three corps, containing ten divisions with over 44,000 effectives, composed Grant's maneuver force during the campaign. Although some recently recruited "green" regiments participated, the bulk of Grant's army consisted of veteran units, many of which had fought with distinction at Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, and Chickasaw Bayou. Of Grant's senior subordinates, the XV Corps commander, Major General William T. Sherman, was his most trusted. Ultimately to prove an exceptional operational commander, Sherman was an adequate tactician with considerable wartime command experience. He and Major General James B. McPherson, commander of XVII Corps, were West Pointers. McPherson was young and inexperienced, but both Grant and Sherman felt he held great promise. Grant's other corps commander, Major General John A. McClernand, was a prewar Democratic congressman who had raised much of his XIII Corps specifically so that he could command an independent Vicksburg expedition. A self-serving and politically ambitious man who neither enjoyed nor curried Grant's favor, he nonetheless was an able organizer and tactical commander who had served bravely at Shiloh. The division commanders were a mix of trained regular officers and volunteers who formed a better-than-average set of Civil War commanders.

Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, a Pennsylvania-born West Pointer who had served with Jefferson Davis in the Mexican War, resigned his federal commission to join the South at the start of the war. Pemberton's army in the Vicksburg campaign consisted of five infantry divisions with no intermediate corps headquarters. Counting two brigades that briefly joined Pemberton's command during the maneuver campaign, he had over 43,000 effectives, many of whom had only limited battle experience. Of Pemberton's subordinates, Brigadier General John S. Bowen, a West Point classmate of McPherson's, was an exceptionally able tactical commander. Major General Carter L. Stevenson was also West Point trained, and the other division commander in the maneuver force, Major General William W. Loring, was a prewar Regular colonel who had worked his way up through the ranks. Significantly, none of these three men had any real respect for their commander and would prove to be less than supportive of him. Pemberton's other division commanders, Major Generals Martin L. Smith and John H. Fomey, both West Pointers, would remain in or near the city, commanding Vicksburg's garrison troops throughout the campaign.

Although Pemberton's five divisions represented the main Confederate force in the Vicksburg campaign, his army came under the jurisdiction of a higher headquarters, General Joseph E. Johnston's Department of the West. Johnston, in 1861, had been the Quartermaster General of the Regular Army and one of only five serving general officers. He had commanded in the eastern theater early in the war until severely wounded. In November 1862 after several months of convalescence, he assumed departmental command in the west. Johnston assumed direct command in Mississippi on 13 May 1863 but was unable to establish effective control over Pemberton's forces. When Pemberton became besieged in Vicksburg, Johnston assembled an Army of Relief but never seriously threatened Grant.

Morale of the troops was a serious concern for both the Union and Confederate commanders. Grant's army suffered terribly from illness in the early months of the campaign, which it spent floundering in the Louisiana swamps. But the men recovered quickly once they gained the high ground across the river. Inured to hardship, these men were served by able commanders and hard working staffs. Once movements started, morale remained high, despite shortfalls in logistical support. Pemberton's men, although not always well served by their commanders, fought hard for their home region through the battle of Champion Hill. Although they briefly lost their resolve after that defeat, once behind the formidable works at Vicksburg, they regained a level of morale and effectiveness that only began to erode weeks later when they were faced with ever-increasing Federal strength and their own supply shortages. [10]

The Armies in the Overland Campaign

The forces in the Overland Campaign evolved through several organizational changes over the course of the two-month struggle. The details of these changes are covered in the campaign overview and in the appendixes. Some key aspects of these organizations are summarized below. On the Union side, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, in addition to being the commander of all of the Union forces arrayed against the Confederacy, commanded all Union forces in the eastern theater of operations that fought in the Overland Campaign. His main force was Major General George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac, which initially consisted of three infantry corps and one cavalry corps. An additional infantry corps, the IX Corps under Major General Ambrose E. Burnside, began the campaign as a separate corps reporting directly to Grant, but was later assigned to the Army of the Potomac. Major General Franz Sigel commanded a Union army in the Shenandoah Valley that had only an indirect role in the Overland Campaign. On the other hand, Major General Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James was more directly involved in the campaign. His army consisted of two infantry corps and about a division’s

worth of cavalry troops. Later in the campaign, at Cold Harbor, one of Butler’s corps, the XVIII under Major General William F. Smith, was temporarily attached to the Army of the Potomac. The initial strength of the Army of the Potomac and the IX Corps at the beginning of the Overland Campaign was slightly under 120,000 men. There are some factors affecting the strength, quality, and organization of the Union forces that should be noted. First, just prior to the campaign, the Army of the Potomac had abolished two of its infantry corps (the I and III Corps, both of which had been decimated at Gettysburg) and consolidated their subordinate units into the remaining three corps (II, V, and VI). This definitely streamlined the Army’s command and control, but it also meant that some divisions and brigades were not accustomed to their new corps’ methods and procedures at the start of the campaign. Second, soldiers in a large number of the Federal regiments were approaching the expiration dates of their enlistments just as the campaign was set to begin in May 1864. Most of the troops in these regiments had enlisted for three years in 1861, and they represented the most experienced fighters in the Army. A surprisingly large number of these soldiers reenlisted (over 50 percent), but there was still a large turnover and much disruption as many of the regiments that reenlisted returned to their home states for furloughs and to recruit replacements. Finally, the Union did tap a new source for soldiers in 1864: the “heavy artillery” regiments. These were units designed to man the heavy artillery in the fortifications around Washington, DC. Grant decided to strip many of these regiments from the forts and use them as infantry in the 1864 campaign, and he employed these forces more extensively as his losses accumulated. The heavy artillery regiments had a slightly different structure than the traditional infantry regiments, and they had not suffered battle casualties; thus, they often still possessed about 1,200 soldiers in a regiment. This was as large as a veteran Union brigade in 1864. On the Confederate side, there was no overall commander in chief or even a theater commander with authority similar to that of Grant. Officially, only President Jefferson Davis had the authority to coordinate separate Confederate armies and military districts. However, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, General Robert E. Lee, had considerable influence over affairs in the entire eastern theater due to the immense respect he had earned from Davis and other Confederate leaders. Lee’s army consisted of three infantry corps and a cavalry corps. One of these corps (Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s I Corps) had been on detached duty just prior to the opening of the campaign and would not join the rest of Lee’s army until the second day of the battle of the Wilderness

(6 June). Additional Confederate forces in the theater included Major General John C. Breckinridge’s small army in the Shenandoah Valley and General P.G.T. Beauregard’s forces protecting Richmond, southern Virginia, and northern North Carolina. In the course of the campaign, Lee received some reinforcements from both Breckinridge and Beauregard. The Army of Northern Virginia (including Longstreet’s I Corps) began the campaign with about 64,000 soldiers. Although plagued by an overall shortage in numbers, Lee had fewer worries about the organization and quality of his manpower. Most of his soldiers had enlisted for the duration of the war, thus his army lost few regiments due to expired terms of service. Also, thanks to its better replacement system, Confederate regiments were usually closer to a consistent strength of 350 to 600 men instead of the wild disparity of their Union counterparts (as low as 150 soldiers in the decimated veteran regiments and as much as 1,200 in the heavy artillery regiments). Overall, Lee could count on the quality and consistency of his units, and he did not have to endure the turmoil of troop turnover and organizational changes that hindered Grant’s forces. As for staffs, on the Union side Grant maintained a surprisingly small staff for a commander in chief. His personal chief of staff was Major General John A. Rawlins, a capable officer who generally produced concise and well‑crafted orders. In addition, he was Grant’s alter ego, a trusted friend who took it upon himself to keep Grant sober. In fact, recent scholarship indicates that Grant’s drinking was far less of a problem than formerly indicated, and there were certainly no drinking difficulties during the Overland Campaign. The rest of Grant’s small staff consisted of a coterie of friends who had earned Grant’s trust from their common service in the western theater campaigns. In general, this staff performed well, although a few glaring mistakes would come back to haunt the Union effort. Of course, one of the major reasons Grant could afford to keep such a small staff in the field was that the chief of staff for the Union armies, Major General Henry W. Halleck, remained in Washington with a large staff that handled Grant’s administrative duties as general in chief. In fact, Halleck was a superb staff officer who tactfully navigated the political seas of Washington and gave Grant the freedom to accompany the Army of the Potomac in the field. In contrast to Grant’s field staff, Meade had a huge staff that Grant once jokingly described as fitting for an Imperial Roman Emperor. Meade’s chief of staff was Major General Andrew A. Humphreys, an extremely capable officer who only reluctantly agreed to leave field command to

serve on the army’s staff. Humphreys has received some criticism for not pushing the Army of the Potomac through the Wilderness on 4 May; but for most of the campaign, his orders were solid and his movement plan for the crossing of the James River was outstanding. Another excellent officer on the army staff was the chief of artillery, Major General Henry J. Hunt. Recognized as one of the war’s foremost experts on artillery, Hunt had a more active role in operational matters than most artillery chiefs who usually just performed administrative duties. The rest of Meade’s staff was of mixed quality. In addition, the poor caliber of Union maps coupled with some mediocre young officers who were used as guides repeatedly led to misdirected movements and lost time. Compared to Meade’s large headquarters, Lee maintained a smaller group of trusted subordinates for his staff. Lee did not have a chief of staff, thus much of the responsibility for writing his orders fell on the shoulders of a few personal aides and secretaries, especially Lieutenant Colonel Charles Marshall. Lee employed several young officers, such as Lieutenant Colonel Walter Taylor and Colonel Charles S. Venable, as aides, and had great faith in these men to transmit his orders to subordinates. However, the lack of a true staff to ease his workload probably took its toll on Lee who was ill and physically exhausted by the time of the North Anna battles at the end of May. Other than his young aides, Lee had several other staff officers of mixed quality. His chief of artillery, Brigadier General William N. Pendleton, was mediocre at best, and the Army commander usually relegated his chief of artillery to strictly administrative duties. On the other hand, Major General Martin Luther (M.L.) Smith, Lee’s chief engineer, played an active and generally positive role throughout the campaign.[11]

Weapons

Infantry

During the 1850s, in a technological revolution of major proportions, the rifle musket began to replace the relatively inaccurate smoothbore musket in ever-increasing numbers, both in Europe and America. This process, accelerated by the Civil War, ensured that the rifled shoulder weapon would be the basic weapon used by infantrymen in both the Federal and Confederate armies. The standard and most common shoulder weapon used in the American Civil War was the Springfield .58‑caliber rifle musket, models 1855, 1861, and 1863. In 1855, the US Army adopted this weapon to replace the .69‑caliber smoothbore musket and the .54‑caliber rifle. In appearance, the rifle musket was similar to the smoothbore musket. Both were single‑shot muzzleloaders, but the rifled bore of the new weapon substantially increased its range and accuracy. The rifling system chosen by the United States was designed by Claude Minié, a French Army officer. Whereas earlier rifles fired a round nonexpanding ball, the Minié system used a hollow‑based cylindro‑conoidal projectile slightly smaller than the bore that dropped easily into the barrel. When the powder charge was ignited by a fulminate of mercury percussion cap, the released powder gases expanded the base of the bullet into the rifled grooves, giving the projectile a ballistic spin. The model 1855 Springfield rifle musket was the first regulation arm to use the hollow‑base .58‑caliber minie bullet. The slightly modified model 1861 was the principal infantry weapon of the Civil War, although two subsequent models in 1863 were produced in about equal quantities. The model 1861 was 56 inches long overall, had a 40‑inch barrel, and weighed 9 pounds 2 ounces with its bayonet. The 21-inch socket bayonet consisted of an 18‑inch triangular blade and 3‑inch socket. The Springfield had a rear sight graduated to 500 yards. The maximum effective range of this weapon was approximately 500 yards, although it had killing power at 1,000 yards. The round could penetrate 11 inches of white-pine board at 200 yards and 3¼ inches at 1,000 yards, with a penetration of 1 inch considered the equivalent of disabling a human being. Although the new weapons had increased accuracy and effectiveness, the soldiers’ vision was still obscured by the clouds of smoke produced by the rifle musket’s black powder propellant.

To load a muzzle‑loading rifle, the soldier took a paper cartridge in hand and tore the end of the paper with his teeth. Next, he poured the powder down the barrel and placed the bullet in the muzzle. Then, using a metal ramrod, he pushed the bullet firmly down the barrel until seated. He then cocked the hammer and placed the percussion cap on the cone or nipple, which, when struck by the hammer, ignited the gunpowder. The average rate of fire was three rounds per minute. A well‑trained soldier could possibly load and fire four times per minute, but in the confusion of battle, the rate of fire was probably slower, two to three rounds per minute.

In addition to the Springfields, over 100 types of muskets, rifles, rifle muskets, and rifled muskets—ranging up to .79 caliber—were used during the American Civil War. The numerous American-made weapons were supplemented early in the conflict by a wide variety of imported models. The best, most popular, and most common of the foreign weapons was the British .577‑caliber Enfield rifle, model 1853, which was 54 inches long (with a 39‑inch barrel), weighed 8.7 pounds (9.2 with the bayonet), could be fitted with a socket bayonet with an 18-inch blade, and had a rear sight graduated to 800 yards. The Enfield design was produced in a variety of forms, both long and short barreled, by several British manufacturers and at least one American company. Of all the foreign designs, the Enfield most closely resembled the Springfield in characteristics and capabilities. The United States purchased over 436,000 Enfield‑pattern weapons during the war. Statistics on Confederate purchases are more difficult to ascertain, but a report dated February 1863 indicated that 70,980 long Enfields and 9,715 short Enfields had been delivered by that time, with another 23,000 awaiting delivery. While the quality of imported weapons varied, experts considered the Enfields and the Austrian Lorenz rifle muskets to be very good. However, some foreign governments and manufacturers took advantage of the huge initial demand for weapons by dumping their obsolete weapons on the American market. This practice was especially prevalent with some of the older smoothbore muskets and converted flintlocks. The greatest challenge, however, lay in maintaining these weapons and supplying ammunition and replacement parts for calibers ranging from .44 to .79. The quality of the imported weapons eventually improved as the procedures, standards, and astuteness of the purchasers improved. For the most part, the European suppliers provided needed weapons, and the newer foreign weapons were highly regarded.

Breechloaders and repeating rifles were available by 1861 and were initially purchased in limited quantities, often by individual soldiers. Generally, however, these types of rifles were not issued to troops in large numbers because of technical problems (poor breech seals, faulty ammunition), fear by the Ordnance Department that the troops would waste ammunition, and the cost of rifle production. The most famous of the breechloaders was the single-shot Sharps, produced in both carbine and rifle models. The model 1859 rifle was .52‑caliber, 47⅛ inches long, and weighed 8¾ pounds, while the carbine was .52‑caliber, 39⅛ inches long, and weighed 7¾ pounds. Both weapons used a linen cartridge and a pellet primer feed mechanism. Most Sharps carbines were issued to Federal cavalry units.

The best known of the repeaters was probably the seven‑shot .52‑caliber Spencer, which came in both rifle and carbine models. The rifle was 47‑ inches long and weighed 10 pounds, while the carbine was 39‑inches long and weighed 8¼ pounds. The Spencer was also the first weapon adopted by the US Army that fired a metallic rim‑fire, self‑contained cartridge. Soldiers loaded rounds through an opening in the butt of the stock, which fed into the chamber through a tubular magazine by the action of the trigger guard. The hammer still had to be cocked manually before each shot. The Henry rifle was, in some ways, even better than either the Sharps or the Spencer. Although never adopted by the US Army in any quantity, it was purchased privately by soldiers during the war. The Henry was a 16‑shot, .44‑caliber rimfire cartridge repeater. It was 43½ inches long and weighed 9¼ pounds. The tubular magazine located directly beneath the barrel had a 15‑round capacity with an additional round in the chamber. Of the approximately 13,500 Henrys produced, probably 10,000 saw limited service. The government purchased only 1,731. The Colt repeating rifle, model 1855 (or revolving carbine), also was available to Civil War soldiers in limited numbers. The weapon was produced in several lengths and calibers, the lengths varying from 32 to 42½ inches, while its calibers were .36, .44, and .56. The .36 and .44 calibers were made to chamber six shots, while the .56‑caliber was made to chamber five shots. The Colt Firearms Company was also the primary supplier of revolvers (the standard sidearm for cavalry troops and officers), the .44‑caliber Army revolver and the .36‑caliber Navy revolver being the most popular (over 146,000 purchased). This was because they were simple, relatively sturdy, and reliable.[12]

TYPICAL CIVIL WAR SMALL ARMS

| Weapon | Effective Range (in yards) | Theoretical Rate of Fire (in rounds/minutes) |

| U.S. rifled musket, muzzle-loaded, .58-caliber | 400-600 | 3 |

| English Enfield rifled musket, muzzle-loaded, .577-caliber | 400-600 | 3 |

| Smoothbore musket, muzzle-loaded, .69-caliber | 100-200 | 3 |

Cavalry

Initially armed with sabers and pistols (and in one case, lances), Federal cavalry troops quickly added the breech-loading carbine to their inventory of weapons. Troops preferred the easier-handling carbines to rifles and the breechloaders to awkward muzzleloaders. Of the single‑shot breech-loading carbines that saw extensive use during the Civil War, the Hall .52‑caliber accounted for approximately 20,000 in 1861. The Hall was quickly replaced by a variety of more state-of-the-art carbines, including the Merrill .54‑caliber (14,495), Maynard .52‑caliber (20,002), Gallager .53‑caliber (22,728), Smith .52‑caliber (30,062), Burnside .56‑ caliber (55,567), and Sharps .54‑caliber (80,512). The next step in the evolutionary process was the repeating carbine, the favorite by 1864 (and commonly distributed by 1865) being the Spencer .52‑caliber seven‑shot repeater (94,194). Because of the South’s limited industrial capacity, Confederate cavalrymen had a more difficult time arming themselves. Nevertheless, they too embraced the firepower revolution, choosing shotguns and muzzle-loading carbines as well as multiple sets of revolvers as their primary weapons. In addition, Confederate cavalrymen made extensive use of battlefield salvage by recovering Federal weapons. However, the South’s difficulties in producing the metallic‑rimmed cartridges required by many of these recovered weapons limited their usefulness.[13]

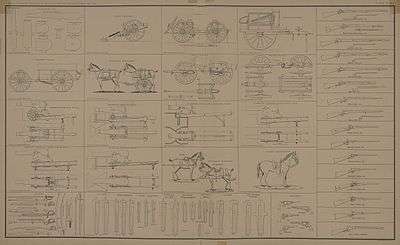

Field Artillery

In 1841, the US Army selected bronze as the standard material for fieldpieces and at the same time adopted a new system of field artillery. The 1841 field artillery system consisted entirely of smoothbore muzzleloaders: 6‑ and 12‑pound guns; 12‑, 24‑, and 32‑pound howitzers; and 12-pound mountain howitzers. A pre-Civil War battery usually consisted of six fieldpieces—four guns and two howitzers. A 6‑pound battery contained four 6-pound guns and two 12-pound howitzers, while a 12-pound battery had four 12-pound guns and two 24-pound howitzers. The guns fired solid shot, shell, spherical case, grapeshot, and canister rounds, while howitzers fired shell, spherical case, grapeshot, and canister rounds (artillery ammunition is described below).

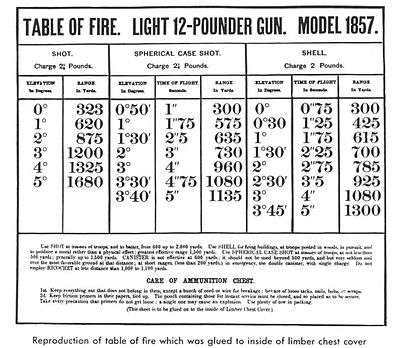

The 6‑pound gun (effective range 1,523 yards) was the primary fieldpiece used from the time of the Mexican War until the Civil War. By 1861, however, the 1841 artillery system based on the 6-pounder was obsolete. In 1857, a new and more versatile fieldpiece, the 12‑pound gun‑howitzer (Napoleon), model 1857, appeared on the scene. Designed as a multipurpose piece to replace existing guns and howitzers, the Napoleon fired canister and shell, like the 12-pound howitzer, and solid shot comparable in range to the 12-pound gun. The Napoleon was a bronze, muzzle-loading smoothbore with an effective range of 1,619 yards (see table 3 for a comparison of artillery data). Served by a nine‑man crew, the piece could fire at a sustained rate of two aimed shots per minute. Like almost all smoothbore artillery, the Napoleon fired “fixed” ammunition—the projectile and powder were bound together with metal bands.

Another new development in field artillery was the introduction of rifling. Although rifled guns provided greater range and accuracy, smoothbores were generally more reliable and faster to load. Rifled ammunition was semifixed, so the charge and the projectile had to be loaded separately. In addition, the canister load of the rifle did not perform as well as that of the smoothbore. Initially, some smoothbores were rifled on the James pattern, but they soon proved unsatisfactory because the bronze rifling eroded too easily. Therefore, most rifled artillery was either wrought iron or cast iron with a wrought-iron reinforcing band. The most commonly used rifled guns were the 10‑pound Parrott and the Rodman, or 3‑inch ordnance rifle. The Parrott rifle was a cast‑iron piece, easily identified by the wrought‑iron band reinforcing the breech. The 10-pound Parrott was made in two models: model 1861 had a 2.9-inch rifled bore with three lands and grooves and a slight muzzle swell, while model 1863 had a 3‑inch bore and no muzzle swell. The Rodman or ordnance rifle was a long‑tubed, wrought‑iron piece that had a 3‑inch bore with seven lands and grooves. Ordnance rifles were sturdier and considered superior in accuracy and reliability to the 10-pound Parrott.

A new weapon that made its first appearance in the war during the Overland Campaign was the 24-pound Coehorn mortar. Used exclusively by the North, the Coehorn fired a projectile in a high arcing trajectory and was ideal for lobbing shells into trenches in siege warfare. The Coehorn was used briefly during the fighting at the “bloody angle” at Spotsylvania and later in the trench lines at Cold Harbor.

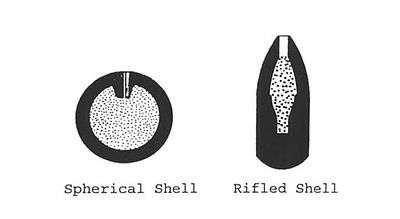

By 1860, the ammunition for field artillery consisted of four general types for both smoothbores and rifles: solid shot, shell, case, and canister. Solid shot was a round cast‑iron projectile for smoothbores and an elongated projectile, known as a bolt, for rifled guns. Solid shot, with its smashing or battering effect, was used in a counterbattery role or against buildings and massed formations. The conical-shaped bolt lacked the effectiveness of the cannonball because it tended to bury itself on impact instead of bounding along the ground like a bowling ball. Shell, also known as common or explosive shell, whether spherical or conical, was a hollow projectile filled with an explosive charge of black powder that was detonated by a fuse. Shell was designed to break into jagged pieces, producing an antipersonnel effect, but the low‑order detonation seldom produced more than three to five fragments. In addition to its casualty-producing effects, shell had a psychological impact when it exploded over the heads of troops. It was also used against field fortifications and in a counterbattery role. Case or case shot for both smoothbore and rifled guns was a hollow projectile with thinner walls than shell. The projectile was filled with round lead or iron balls set in a matrix of sulfur that surrounded a small bursting charge. Case was primarily used in an antipersonnel role. This type of round had been invented by Henry Shrapnel, a British artillery officer, hence the term “shrapnel.”

Last, there was canister, probably the most effective round and the round of choice at close range (400 yards or less) against massed troops. Canister was essentially a tin can filled with iron balls packed in sawdust with no internal bursting charge. When fired, the can disintegrated, and the balls followed their own paths to the target. The canister round for the 12‑pound Napoleon consisted of 27 1½‑inch iron balls packed inside an elongated tin cylinder. At extremely close ranges, men often loaded double charges of canister. By 1861, canister had replaced grapeshot in the ammunition chests of field batteries (grapeshot balls were larger than canister, and thus fewer could be fired per round).[14]

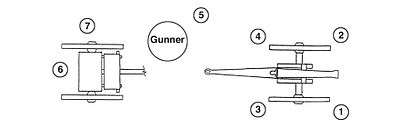

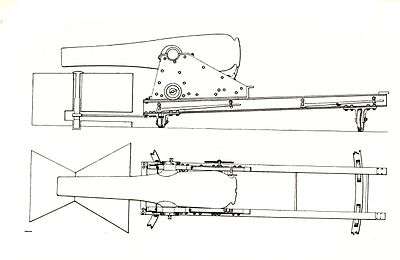

During the firing sequence cannoneers took their positions as in the diagram below. At the command “Commence firing,” the gunner ordered “Load.” While the gunner sighted the piece, Number 1 sponged the bore; Number 5 received a round from Number 7 at the limber and carried the round to Number 2, who placed it in the bore. Number 1 rammed the round to the breech, while Number 3 placed a thumb over the vent to prevent premature detonation of the charge. When the gun was loaded and sighted, Number 3 inserted a vent pick into the vent and punctured the cartridge bag. Number 4 attached a lanyard to a friction primer and inserted the primer into the vent. At the command “Fire,” Number 4 yanked the lanyard. Number 6 cut the fuses, if necessary. The process was repeated until the command to cease firing was given.[15]

Artillery projectiles

Four basic types of projectiles were employed by Civil War field artillery:

SOLID PROJECTILE: Round (spherical) projectiles of solid iron for smooth-bores are commonly called "cannonballs" or just plain "shot." When elongated for rifled weapons, the projectile is known as a "bolt." Shot was used against opposing batteries, wagons, buildings, etc., as well as enemy personnel. While round shot could ricochet across open ground against advancing infantry and cavalry, conical bolts tended to bury themselves upon impact with the ground and therefore were not used a great deal by field artillery.[16]

SHELL: The shell, whether spherical or conical, was a hollow iron projectile filled with a black powder bursting charge. It was designed to break into several ragged fragments. Spherical shells were exploded by fuses set into an opening in the shell, and were ignited by the flame of the cannon's propelling discharge. The time of detonation was determined by adjusting the length of the fuse. Conical shells were detonated by similar timed fuses, or by impact. Shells were intended to impact on the target.[17]

CASE SHOT: Case shot, or "shrapnel" was the invention of Henry Shrapnel, an English artillery officer. The projectile had a thinner wall than a shell and was filled with a number of small lead or iron balls (27 for a 12-pounder). A timed fuse ignited a small bursting charge which fragmented the casing and scattered the contents in the air. Spherical case shot was intended to burst from fifty to seventy five yards short of the target, the fragments being carried forward by the velocity of the shot.[18]

CANISTER: Canister consisted of a tin cylinder in which was packed a number of small iron or lead balls. Upon discharge the cylinder split open and the smaller projectiles fanned out. Canister was an extremely effective anti-personnel weapon at ranges up to 200 yards, and had a maximum range of 400 yards. In emergencies double loads of canister could be used at ranges of less than 200 yards, using a single propelling charge.[19]

Siege Artillery

The 1841 artillery system listed eight types of siege artillery and another six types as seacoast artillery. The 1861 Ordnance Manual included eleven different kinds of siege ordnance. The principal siege weapons in 1861 were the 4.5-inch rifle; 18-, and 24-pounder guns; a 24-pounder howitzer and two types of 8-inch howitzers; and several types of 8- and 10-inch mortars. The normal rate of fire for siege guns and mortars was about twelve rounds per hour, but with a well-drilled crew, this could probably be increased to about twenty rounds per hour. The rate of fire for siege howitzers was somewhat lower, being about eight shots per hour. The carriages for siege guns and howitzers were longer and heavier than field artillery carriages but were similar in construction. The 24-pounder model 1839 was the heaviest piece that could be moved over the roads of the day. Alternate means of transport, such as railroad or watercraft, were required to move larger pieces any great distance. The rounds fired by siege artillery were generally the same as those fired by field artillery, except that siege artillery continued to use grapeshot after it was discontinued in the field artillery (1841). A "stand of grape" consisted of nine iron balls, ranging from two to about three and one-half inches in size depending on the gun caliber. The largest and heaviest artillery pieces in the Civil War era belonged to the seacoast artillery. These large weapons were normally mounted in fixed positions. The 1861 system included five types of columbiads, ranging from 8- to 15-inch; 32- and 42-pounder guns; 8- and 10-inch howitzers; and mortars of 10- and 13-inches. Wartime additions to the Federal seacoast artillery inventory included Parrott rifles, ranging from 6.4-inch to 10-inch (300-pounder). New columbiads, developed by Ordnance Lieutenant Thomas J. Rodman, included 8-inch, 10-inch, and 15-inch models. The Confederates produced some new seacoast artillery of their ownBrooke rifles in 6.4-inch and 7-inch versions. They also imported weapons from England, including 7- and 8-inch Armstrong rifles, 6.3-tol2.5-inch Blakely rifles, and 5-inch Whitworth rifles. Seacoast artillery fired the same projectiles as siege artillery but with one addition - hot shot. As its name implies, hot shot was solid shot heated in special ovens until red-hot, then carefully loaded and fired as an incendiary round.[20]

Naval Ordnance

Like the Army, the U.S. Navy in the Civil War possessed an artillery establishment that spanned the spectrum from light to heavy. A series of light boat guns and howitzers corresponded to the Army's field artillery. Designed for service on small boats and launches, this class of weapon included 12- and 24-pounder pieces, both smoothbore and rifled. The most successful boat gun was a 12-pounder smoothbore howitzer (4.62-inch bore) designed by John A. Dahlgren, the Navy's premier ordnance expert and wartime chief of ordnance. Typically mounted in the bow of a small craft, the Dahlgren 12-pounder could be transferred, in a matter of minutes, to an iron field carriage for use on shore. This versatile little weapon fired shell and case rounds.

Naturally, most naval artillery was designed for ship killing. A variety of 32-pounder guns (6.4-inch bore) produced from the 1820s through the 1840s remained in service during the Civil War. These venerable smoothbores, direct descendants of the broadside guns used in the Napoleonic Wars, fired solid shot and were effective not only in ship-to-ship combat but also in the shore-bombardment role.

A more modern class of naval artillery weapons was known as "shellguns." These were large-caliber smoothbores designed to shoot massive exploding shells that were capable of dealing catastrophic damage to a wooden-hulled vessel. Shellguns could be found both in broadside batteries and in upper-deck pivot mounts, which allowed wide traverse. An early example of the shellgun, designed in 1845 but still in service during the Civil War, was an 8-inch model that fired a 51-pound shell.

John Dahlgren's design came to typify the shellgun class of weapons. All of his shellguns shared an unmistakable "beer-bottle" shape. The most successful Dahlgren shellguns were a 9-inch model (72.5-pound shell or 90-pound solid shot), an 11-inch (136-pound shell or 170-pound solid shot), and a 15-inch, which fired an awesome 330-pound shell or 440-pound solid shot. A pivot-mounted 11-inch shellgun proved to be the decisive weapon in the U.S.S. Kearsarge's 1864 victory over the C.S.S. Alabama. The famous U.S. Navy ironclad Monitor mounted two 11-inch Dahlgrens in its rotating turret. Later monitors carried 15-inch shellguns.

The U.S. Navy also made wide use of rifled artillery. These high-velocity weapons became increasingly important with the advent of ironclad warships. Some Navy rifles were essentially identical to Army models. For instance, the Navy procured Parrott rifles in 4.2-inch, 6.4-inch, 8-inch, and 10-inch versions, each of which had a counterpart in the Army as either siege or seacoast artillery. Other rifled weapons, conceived specifically for naval use, included two Dahlgren designs. The 50-pounder (with approximately 5-inch bore) was the better of the two Dahlgren rifles. An 80-pounder model (6-inch bore) was less popular, due to its tendency to burst.

The Confederacy relied heavily on British imports for its naval armament Naval variants of Armstrong, Whitworth, and Blakely weapons all saw service. In addition, the Confederate Navy used Brooke rifles manufactured in the South. The Confederacy also produced a 9-inch version of the Dahlgren shellgun that apparently found use both afloat and ashore.[21]

| Type | Model | Bore Dia (in.) | Length (in.) | Tube wt. (lbs.) | Carriage wt. (lbs.) | Range (yds) /deg. elev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field Artillery | ||||||

| Smoothbores | ||||||

| 6-pounder | Gun | 3.67 | 65.6 | 884 | 900 | 1,513/5° |

| 12-pounder "Napoleon" | Gun Howitzer | 4.62 | 72.15 | 1,227 | 1.128 | 1,680/5° |

| 12-pounder | Howitzer | 4.62 | 58.6 | 788 | 900 | 1,072/5° |

| 24-pounder | Howitzer | 5.82 | 71.2 | 1,318 | 1,128 | 1,322/5° |

| Rifles | ||||||

| 10-pounder | Parrot | 3.0 | 78 | 890 | 900 | 2,970/10° |

| 3-inch | Ordnance | 3.0 | 73-3 | 820 | 900 | 2,788/10° |

| 20-pounder | Parrot | 3.67 | 89.5 | 1,750 | 4,4011/15° | |

| Siege and Garrison | ||||||

| Smoothbores | ||||||

| 8-inch | Howitzer | 8.0 | 61.5 | 2,614 | 50.5 shell | 2,280/12°30' |

| 10-inch | Mortar | 10.0 | 28.0 | 1,852 | 87.5 shell | 2,028/45° |

| 12-pounder | Gun | 4.62 | 116.0 | 3,590 | 12.3 shot | |

| 24-pounder | Gun | 5.82 | 124.0 | 5,790 | 24.4 shot | 1,901/5° |

| Rifles | ||||||

| 18-pounder* | Gun (Rifled) | 5-3 | 123.25 | |||

| 30-pounder | Parrot | 4.2 | 132.5 | 4,200 | 29.0 shell | 6,700/25° |

| *The Confederate "Whistling Dick," a obsolete smoothbore siege gun, rifled and banded. | ||||||

| Seacost | ||||||

| Smoothbores | ||||||

| 8-inch | Columbiad | 8.0 | 124 | 9,240 | 65 shot | 4,812/27°30' |

| 9-inch* | Dahlgren | 9.0 | ||||

| 10-inch | Columbiad | 10-0 | 126 | 15,400 | 128 shot | 5,654/39° 15' |

| 11-inch | Dahlgren | 11-0 | 161 | 15,700 | 3,650/20' | |

| 32-pounder | Gun | 6-4 | 125-7 | 7,200 | 32-6 shot | 1,922/5° |

| 42-pounder | Gun | 7-0 | 129 | 8,465 | 42.7 shot | 1,955/5° |

| Rifles | ||||||

| 6.4-inch | Brooke | 6.4 | 144 | 9,120 | ||

| 7-inch | Brooke | 7-0 | 147.5 | 14,800 | ||

| 7.5. inch** | Blakely | 7.5 | 100 | |||

| 100-pounder | Parrott | 6-4 | 155 | 9,700 | 100 shot | 2,247/5° |

| A Confederate produced copy of Dahlgren's basic design. | ||||||

| **The famous Confederate "Widow Blakel," Probably a British 42-pounder smoothbore shortened, banded, and rifled. | ||||||

| NAVAL | ||||||

| Type | Model | Bore Dia (in) | Tube Length (in) | Tube wt (lbs) | Projectile wt. (lbs) | Range (yds) /deg. elev. |

| Smoothbores | ||||||

| 8- inch | Dahlgren | 8 | 115.5 | 6,500 | 51 shell | 1,657/5° |

| 9-inch | Dahlgren | 9 | 131.5 | 9,000 | 72-5 shell | 1,710/5° |

| 11-inch | Dahlgren | 11 | 161 | 15,700 | 136 shell | 1,712/5° |

| 12-pounder | Howitzer | 4.62 | 63.5 | 760 | 10 hell | 1,08515° |

| 24-pounder | Howitzer | 5.82 | 67 | 1,310 | 20 shell | 1,270/5° |

| 32-pounder | Gun | 6-4 | 108 | 4,704 | 32 shot | 1,756/5° |

| 64-pounder | Gun | 8 | 140.95 | 11,872 | ||

| Rifles | ||||||

| 30- pounder | Parrott | 4.2 | 112 | 3,550 | 29 shell | 2,200/5º |

| 42-pounder** | Gun(rifled) | 7 | 121 | 7,870 | 42 shot | |

| 50-pounder | Dahlgren | 5.1 | 107 | 6,000 | 50 shot | |

| 100-pounder | Patron | 6.4 | 155 | 9,700 | 100 shot | 2,200/5° |

| Mortar | ||||||

| 13-inch | Mortar | 13 | 54.5 | 17,120 | 200 bell | 4,200/45° |

| Some naval guns served ashore as siege artillery. Moreover, many guns mounted on the boats of the Mississippi River Squadron were in fact Army field artillery and siege guns. | ||||||

| "Converted smoothbore. | ||||||

Weapons at Vicksburg

The wide variety of infantry weapons available to Civil War armies is clearly evident at Vicksburg. A review of the Quarterly Returns of Ordnance for April-June 1863 reveals that approximately three-quarters of Grant's Army of the Tennessee carried "first class" shoulder weapons, the most numerous of which were British 1853 Enfield rifle-muskets (.577 caliber). Other "first class" weapons used in the Vicksburg campaign included American-made Springfield rifle-muskets (.58 caliber), French rifle-muskets (.58 caliber), French "light" or "Liege" rifles (.577 caliber), U.S. Model 1840/45 rifles (.58 caliber), Dresden and Suhl rifle-muskets (.58 caliber), and Sharps breechloading carbines (.52 caliber). Approximately thirty-five Federal regiments (roughly one-quarter of the total) were armed primarily with "second class" weapons, such as Austrian rifle-muskets in .54, .577, and .58 calibers; U.S. Model 1841 rifled muskets (.69 caliber); U.S. Model 1816 rifled muskets altered to percussion (.69 caliber); Belgian and French rifled muskets (.69 and .71 calibers); Belgian or Vincennes rifles (.70 and .71 calibers); and both Austrian and Prussian rifled muskets in .69 and .70 calibers. Only one Federal regiment, the 101st Illinois Infantry, was armed with "third class" weapons, such as the U.S. Model 1842 smoothbore musket (.69 caliber), Austrian, Prussian, and French smoothbore muskets (.69 caliber), and Austrian and Prussian smoothbore muskets of.72 caliber. After the surrender of Vicksburg, the 101 st Illinois, along with about twenty regiments armed with "second class" arms, exchanged its obsolete weapons for captured Confederate rifle-muskets.

Although the Confederate records are incomplete, it seems that some 50,000 shoulder weapons were surrendered at Vicksburg, mostly British-made Enfields. Other weapons included a mix of various .58-caliber "minié" rifles (Springfield, Richmond, Mississippi and Fayetteville models), Austrian and French rifle-muskets in .577 and .58 calibers, Mississippi rifles, Austrian rifle-muskets (.54 caliber), various .69-caliber rifled muskets altered to percussion, Belgian .70-caliber rifles, and British smoothbore muskets in .75 caliber.

The diversity of weapons (and calibers of ammunition) obviously created serious sustainment problems for both sides. Amazingly, there is little evidence that ammunition shortages had much influence on operations (the Vicksburg defenders surrendered 600,000 rounds and 350,000 percussion caps), even though the lack of weapons standardization extended down to regimental levels.

Whereas there was little to differentiate Union from Confederate effectiveness so far as small arms were concerned, the Union forces at Vicksburg enjoyed a clear superiority in terms of artillery. When Grant's army closed on Vicksburg to begin siege operations, it held about 180 cannon. At the height of its strength during the siege, the Union force included some forty-seven batteries of artillery for a total of 247 guns-13 "heavy" guns and 234 "field" pieces. Twenty-nine of the Federal batteries contained six guns each; the remaining eighteen were considered four-gun batteries. Smoothbores outnumbered rifles by a ratio of roughly two to one.

No account of Union artillery at Vicksburg would be complete without an acknowledgment of the U.S. Navy's contributions. Porter's vessels carried guns ranging in size from 12-pounder howitzers to 11-inch Dahlgren shellguns. The Cairo, which is on display today at Vicksburg, suggests both the variety and the power of naval artillery in this campaign. When she sank in December 1862, the Cairo went down with three 42-pounder (7-inch bore) Army rifles, three 64-pounder (8-inch bore) Navy smoothbores, six 32-pounder (6.4-inch bore) Navy smoothbores, and one 4.2-inch 30-pounder Parrott rifle. Porter's firepower was not restricted to the water. During the siege, naval guns served ashore as siege artillery.

The Confederates possessed a sizeable artillery capability but could not match Federal firepower. Taken together, the Confederate forces under Pemberton and Johnston possessed a total of about 62 batteries of artillery with some 221 tubes. Pemberton's force besieged in Vicksburg included 172 cannon-approximately 103 fieldpieces, and 69 siege weapons. Thirty-seven of the siege guns, plus thirteen fieldpieces, occupied positions overlooking the Mississippi. (The number of big guns along the river dropped to thirty-one by the end of the siege-apparently some weapons were shifted elsewhere.) The thirteen field pieces were distributed along the river to counter amphibious assault. The heavy ordnance was grouped into thirteen distinct river-front batteries. These large river-defense weapons included twenty smoothbores, ranging in size from 32-pounder siege guns to 10-inch Columbiads, and seventeen rifled pieces, ranging from a 2.75-inch Whitworth to a 7.44-inch Blakely.

In most of the engagements during the Vicksburg campaign, the Union artillery demonstrated its superiority to that of the Confederates. During the siege, that superiority grew into dominance. The Confederates scattered their artillery in one- or two-gun battery positions sited to repel Union assaults. By declining to mass their guns, the Confederates could do little to interfere with Union siege operations. By contrast, Union gunners created massed batteries at critical points along the line. These were able both to support siege operations with concentrated fires and keep the Confederate guns silent by smothering the embrasures of the small Confederate battery positions. As the siege progressed, Confederate artillery fire dwindled to ineffective levels, whereas the Union artillery blasted away at will. As much as any other factor, Union fire superiority sealed the fate of the Confederate army besieged in Vicksburg.[22]

Weapons in the Overland Campaign

The variety of weapons available to both armies during the Civil War is reflected in the battles of the Overland Campaign. To a limited extent, the Army of Northern Virginia’s infantry had more uniformity in its small arms than the Army of the Potomac. In fact, some regiments of the famous Pennsylvania Reserves Brigade were still equipped with smoothbore muskets. In any case, both armies relied heavily on the Springfield and Enfield, which were the most common weapons used (although almost every other type of Civil War small arms could be found in the campaign). The variety of weapons and calibers of ammunition required on the battlefield by each army presented sustainment challenges that ranged from production and procurement to supplying soldiers in the field. Amazingly, operations were not often affected by the need to resupply a diverse mixture of ammunition types.

The Army of the Potomac (including the IX Corps) started the campaign with 58 batteries of artillery. Of these, 42 were six‑gun batteries, while the other 16 batteries were of the four-gun type. The Federals went to a four-gun battery system after the battle of Spotsylvania. Also at this time, the Army of the Potomac’s Artillery Reserve was disbanded except for the ammunition train. The Reserve’s batteries went to the corps‑level reserve artillery brigades. The Army of Northern Virginia totaled 56 artillery batteries. The vast majority of these (42) were four‑gun batteries. The rest of the mix included one six‑gun battery, three five‑gun, five three‑gun, four two‑gun, and a lone one‑gun battery. (Refer to table 3 for the major types of artillery available to the two armies at the start of the campaign.)

The effectiveness of artillery during the campaign was mixed. In the Wilderness, the rugged terrain and the dense vegetation reduced the effectiveness of artillery fire. Specifically, the Federals’ advantage in numbers of longer‑range rifled guns was negated by the lack of good fields of fire. The more open ground at Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor allowed for better use of artillery. However, the increasing use of entrenchments on both sides tended to relegate artillery to a defensive role.

The Confederates tended to keep their batteries decentralized, usually attached to the infantry brigades within the divisions to which they were assigned. Lee’s army did not have an artillery reserve. The Union tended to centralize their artillery, even after disbanding the army-level reserve. This often meant keeping reserve batteries at corps-level, other batteries in division reserves, and occasionally assigning batteries to brigades as needed. In the Overland Campaign, the Confederate cavalry had an advantage over its Union counterpart in reconnaissance and screening missions. This was largely due to personalities and the mission focus of the two sides, rather than to any organizational or tactical differences between them. The Army of the Potomac’s cavalry corps was commanded by Major General Philip H. Sheridan, who clashed with the Army commander, Meade, over the role of the cavalry. After the opening of the Spotsylvania fight, Sheridan got his wish and conducted a large raid toward Richmond. Stuart countered with part of his force, but the remaining Confederate cavalry kept Lee well informed while the Federals were almost blind. Stuart was killed at the battle of Yellow Tavern, but his eventual replacement, Major General Wade Hampton, filled in admirably. Later in the war, Sheridan would make better use of the cavalry as a striking force, but he never really mastered its reconnaissance role.[23]

Tactics

Tactical Doctrine in 1861

The Napoleonic Wars and the Mexican War were the major influences on American military thinking at the beginning of the Civil War. American military leaders knew of the Napoleonic driven theories of Jomini, while tactical doctrine reflected the lessons learned in Mexico (1846‑48). However, these tactical lessons were misleading, because in Mexico relatively small armies fought only seven pitched battles. In addition, these battles were so small that almost all the tactical lessons learned during the war focused at the regimental, battery, and squadron levels. Future Civil War leaders had learned very little about brigade, division, and corps maneuvers in Mexico, yet these units were standard fighting elements of both armies in 1861‑65.

The US Army’s experience in Mexico validated many Napoleonic principles—particularly that of the offensive. In Mexico, tactics did not differ greatly from those of the early 19th century. Infantry marched in columns and deployed into lines to fight. Once deployed, an infantry regiment might send one or two companies forward as skirmishers, as security against surprise, or to soften the enemy’s line. After identifying the enemy’s position, a regiment advanced in closely ordered lines to within 100 yards. There it delivered a devastating volley, followed by a charge with bayonets. Both sides attempted to use this basic tactic in the first battles of the Civil War with tragic results.

In Mexico, American armies employed artillery and cavalry in both offensive and defensive battle situations. In the offense, artillery moved as near to the enemy lines as possible—normally just outside musket range— in order to blow gaps in the enemy’s line that the infantry might exploit with a determined charge. In the defense, artillery blasted advancing enemy lines with canister and withdrew if the enemy attack got within musket range. Cavalry guarded the army’s flanks and rear but held itself ready to charge if enemy infantry became disorganized or began to withdraw. These tactics worked perfectly well with the weapons technology of the Napoleonic and Mexican Wars. The infantry musket was accurate up to 100 yards, but ineffective against even massed targets beyond that range. Rifles were specialized weapons with excellent accuracy and range but slow to load and, therefore, not usually issued to line troops. Smoothbore cannon had a range up to 1 mile with solid shot, but were most effective against infantry when firing canister at ranges under 400 yards (and even better at 200 yards or less). Artillerists worked their guns without much fear of infantry muskets, which had a limited range. Cavalry continued to use sabers and lances as shock weapons.

American troops took the tactical offensive in most Mexican War battles with great success, and they suffered fairly light losses. Unfortunately, similar tactics proved to be obsolete in the Civil War in part because of the innovation of the rifle musket. This new weapon greatly increased the infantry’s range and accuracy and loaded as fast as a musket. By the beginning of the Civil War, rifle muskets were available in moderate numbers. It was the weapon of choice in both the Union and Confederate armies during the war; by 1864, the vast majority of infantry troops on both sides had rifle muskets of good quality.

Official tactical doctrine prior to the beginning of the Civil War did not clearly recognize the potential of the new rifle musket. Prior to 1855, the most influential tactical guide was General Winfield Scott’s three‑volume work, Infantry Tactics (1835), based on French tactical models of the Napoleonic Wars. It stressed close-order, linear formations in two or three ranks advancing at “quick time” of 110 steps (86 yards) per minute. In 1855, to accompany the introduction of the new rifle musket, Major William J. Hardee published a two‑volume tactical manual, Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics. Hardee’s work contained few significant revisions of Scott’s manual. His major innovation was to increase the speed of the advance to a “double‑quick time” of 165 steps (151 yards) per minute. If, as suggested, Hardee introduced his manual as a response to the rifle musket, then he failed to appreciate the weapon’s full impact on combined arms tactics and the essential shift that the rifle musket made in favor of the defense. Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics was the standard infantry manual used by both sides at the outbreak of war in 1861. If Scott’s and Hardee’s works lagged behind technological innovations, at least the infantry had manuals to establish a doctrinal basis for training. Cavalry and artillery fell even further behind in recognizing the potential tactical shift in favor of rifle‑armed infantry. The cavalry’s manual, published in 1841, was based on French sources that focused on close-order offensive tactics. It favored the traditional cavalry attack in two ranks of horsemen armed with sabers or lances. The manual took no notice of the rifle musket’s potential, nor did it give much attention to dismounted operations. Similarly, the artillery had a basic drill book delineating individual crew actions, but it had no tactical manual. Like cavalrymen, artillerymen showed no concern for the potential tactical changes that the rifle musket implied.[24]

Early War Tactics In the battles of 1861 and 1862, both sides employed the tactics proven in Mexico and found that the tactical offensive could still occasionally be successful—but only at a great cost in casualties. Men wielding rifled weapons in the defense generally ripped incoming frontal assaults to shreds, and if the attackers paused to exchange fire, the slaughter was even greater. Rifles also increased the relative number of defenders that could engage an attacking formation, since flanking units now engaged assaulting troops with a murderous enfilading fire. Defenders usually crippled the first assault line before a second line of attackers could come forward in support. This caused successive attacking lines to intermingle with survivors to their front, thereby destroying formations, command, and control. Although both sides occasionally used the bayonet throughout the war, they quickly discovered that rifle musket fire made successful bayonet attacks almost impossible.