Aplastic anemia

| Aplastic anemia | |

|---|---|

| aplastic anaemia | |

|

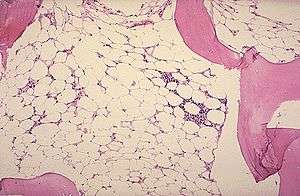

Micrograph of bone marrow taken from a patient with aplastic anemia | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Oncology, hematology |

| ICD-10 | D60-D61 |

| ICD-9-CM | 284 |

| OMIM | 609135 |

| DiseasesDB | 866 |

| MedlinePlus | 000554 |

| eMedicine | med/162 |

| MeSH | D000741 |

Aplastic anemia is a rare disease in which the bone marrow and the hematopoietic stem cells that reside there are damaged.[1] This causes a deficiency of all three blood cell types (pancytopenia): red blood cells (anemia), white blood cells (leukopenia), and platelets (thrombocytopenia).[2][3] Aplastic refers to inability of the stem cells to generate mature blood cells.

It is most prevalent in people in their teens and twenties, but is also common among the elderly. It can be caused by exposure to chemicals, drugs, radiation, immune disease, and heredity. However, in about half the cases, the cause is unknown.[2][3]

The definitive diagnosis is by bone marrow biopsy; normal bone marrow has 30–70% blood stem cells, but in aplastic anemia, these cells are mostly gone and replaced by fat.[2][3]

First line treatment for aplastic anemia consists of immunosuppressive drugs, typically either anti-lymphocyte globulin or anti-thymocyte globulin, combined with corticosteroids and ciclosporin. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is also used, especially for patients under 30 years of age with a related matched marrow donor.[2][3]

Signs and symptoms

Anemia may lead to malaise, pallor and associated symptoms such as palpitations.[4]

Low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia) if present is associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage, bruising and petechiae. Low white blood cell counts (leukocytopenia) if present leads to an increased risk of infections which can be severe.[4]

Causes

Aplastic anemia can be caused by exposure to certain chemicals, drugs, radiation, infection, immune disease; in about half the cases, the cause is unknown. It is not a familial line hereditary condition, nor is it contagious. It can be acquired due to exposure to other conditions but if a person develops the condition, their offspring would not develop it by virtue of their gene connection.[2][3]

Aplastic anemia is also sometimes associated with exposure to toxins such as benzene, or with the use of certain drugs, including chloramphenicol, carbamazepine, felbamate, phenytoin, quinine, and phenylbutazone. Many drugs are associated with aplasia mainly according to case reports, but at a very low probability. As an example, chloramphenicol treatment is followed by aplasia in less than one in 40,000 treatment courses, and carbamazepine aplasia is even rarer.

Exposure to ionizing radiation from radioactive materials or radiation-producing devices is also associated with the development of aplastic anemia. Marie Curie, famous for her pioneering work in the field of radioactivity, died of aplastic anemia after working unprotected with radioactive materials for a long period of time; the damaging effects of ionizing radiation were not then known.[5]

Aplastic anemia is present in up to 2% of patients with acute viral hepatitis.[6]

One known cause is an autoimmune disorder in which white blood cells attack the bone marrow.

Short-lived aplastic anemia can also be a result of parvovirus infection.[7] In humans, the P antigen (also known as globoside), one of the many cellular receptors that contribute to a person's blood type, is the cellular receptor for parvovirus B19 virus that causes erythema infectiosum (fifth disease) in children. Because it infects red blood cells as a result of the affinity for the P antigen, Parvovirus causes complete cessation of red blood cell production. In most cases, this goes unnoticed, as red blood cells live on average 120 days, and the drop in production does not significantly affect the total number of circulating red blood cells. In people with conditions where the cells die early (such as sickle cell disease), however, parvovirus infection can lead to severe anemia.

In some animals, aplastic anemia may have other causes. For example, in the ferret (Mustela putorius furo), it is caused by estrogen toxicity, because female ferrets are induced ovulators, so mating is required to bring the female out of heat. Intact females, if not mated, will remain in heat, and after some time the high levels of estrogen will cause the bone marrow to stop producing red blood cells.

Diagnosis

The condition needs to be differentiated from pure red cell aplasia. In aplastic anemia, the patient has pancytopenia (i.e., anemia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia) resulting in decrease of all formed elements. In contrast, pure red cell aplasia is characterized by reduction in red cells only. The diagnosis can only be confirmed on bone marrow examination. Before this procedure is undertaken, a patient will generally have had other blood tests to find diagnostic clues, including a complete blood count, renal function and electrolytes, liver enzymes, thyroid function tests, vitamin B12 and folic acid levels.

The following tests aid in determining differential diagnosis for aplastic anemia:

- Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy: to rule out other causes of pancytopenia (i.e. neoplastic infiltration or significant myelofibrosis).

- History of iatrogenic exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy: can cause transient bone marrow suppression

- X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, or ultrasound imaging tests: enlarged lymph nodes (sign of lymphoma), kidneys and bones in arms and hands (abnormal in Fanconi anemia)

- Chest X-ray: infections

- Liver tests: liver diseases

- Viral studies: viral infections

- Vitamin B12 and folate levels: vitamin deficiency

- Blood tests for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- Test for antibodies: immune competency

Treatment

Treating immune-mediated aplastic anemia involves suppression of the immune system, an effect achieved by daily medicine intake, or, in more severe cases, a bone marrow transplant, a potential cure.[8] The transplanted bone marrow replaces the failing bone marrow cells with new ones from a matching donor. The multipotent stem cells in the bone marrow reconstitute all three blood cell lines, giving the patient a new immune system, red blood cells, and platelets. However, besides the risk of graft failure, there is also a risk that the newly created white blood cells may attack the rest of the body ("graft-versus-host disease"). In young patients with an HLA matched sibling donor, bone marrow transplant can be considered as first-line treatment, patients lacking a matched sibling donor typically pursue immunosuppression as a first-line treatment, and matched unrelated donor transplants are considered a second-line therapy.

Medical therapy of aplastic anemia often includes a course of antithymocyte globulin (ATG) and several months of treatment with ciclosporin to modulate the immune system. Chemotherapy with agents such as cyclophosphamide may also be effective but has more toxicity than ATG. Antibody therapy, such as ATG, targets T-cells, which are believed to attack the bone marrow. Corticosteroids are generally ineffective, though they are used to ameliorate serum sickness caused by ATG. Normally, success is judged by bone marrow biopsy 6 months after initial treatment with ATG.[9]

One prospective study involving cyclophosphamide was terminated early due to a high incidence of mortality, due to severe infections as a result of prolonged neutropenia.[9]

In the past, before the above treatments became available, patients with low leukocyte counts were often confined to a sterile room or bubble (to reduce risk of infections), as in the case of Ted DeVita.[10]

Follow-up

Regular full blood counts are required on a regular basis to determine whether the patient is still in a state of remission.

Many patients with aplastic anemia also have clones of cells characteristic of the rare disease paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH, anemia with thrombopenia and/or thrombosis), sometimes referred to as AA/PNH. Occasionally PNH dominates over time, with the major manifestation intravascular hemolysis. The overlap of AA and PNH has been speculated to be an escape mechanism by the bone marrow against destruction by the immune system. Flow cytometry testing is performed regularly in people with previous aplastic anemia to monitor for the development of PNH.

Prognosis

Untreated, severe aplastic anemia has a high risk of death. Modern treatment, by drugs or stem cell transplant, has a five-year survival rate that exceeds 85%, with younger age associated with higher survival.[11]

Survival rates for stem cell transplant vary depending on age and availability of a well-matched donor. Five-year survival rates for patients who receive transplants have been shown to be 82% for patients under age 20, 72% for those 20–40 years old, and closer to 50% for patients over age 40. Success rates are better for patients who have donors that are matched siblings and worse for patients who receive their marrow from unrelated donors.[12]

Older people (who are generally too frail to undergo bone marrow transplants), and people who are unable to find a good bone marrow match, undergoing immune suppression have five-year survival rates of up to 75%.

Relapses are common. Relapse following ATG/ciclosporin use can sometimes be treated with a repeated course of therapy. In addition, 10-15% of severe aplastic anemia cases evolve into MDS and leukemia. According to a study, for children who underwent immunosuppressive therapy, about 15.9% of children who responded to immunosuppressive therapy encountered relapse.[13]

Milder disease can resolve on its own.

See also

- Fanconi anemia

- Acquired pure red cell aplasia

- Cause of death of Eleanor Roosevelt

- Cause of death of Marie Curie

References

- ↑ Acton, Ashton (22 July 2013). Aplastic Anemia. ScholarlyEditions. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4816-5068-7.

Aplastic anemia (AA) is a rare bone marrow failure disorder with high mortality rate, which is characterized by pancytopenia and an associated increase in the risk of hemorrhage, infection, organ dysfunction and death.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kasper, Dennis L; Braunwald, Eugene; Fauci, Anthony; et al. (2005). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-140235-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Merck Manual, Professional Edition, Aplastic Anemia (Hypoplastic Anemia)

- 1 2 Peinemann, F; Bartel, C; Grouven, U (23 July 2013). "First-line allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation of HLA-matched sibling donors compared with first-line ciclosporin and/or antithymocyte or antilymphocyte globulin for acquired severe aplastic anemia.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 7: CD006407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006407.pub2. PMID 23881658.

- ↑ "Marie Curie - The Radium Institute (1919-1934): Part 3". American Institute of Physics.

- ↑ Clark, Michael; Kumar, Parveen, eds. (July 2011). Kumar & Clark's clinical medicine (7th ed.). Edinburgh: Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-2992-9.

- ↑ Aplastic Anemia: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional. ScholarlyEditions. 22 July 2013. p. 39. ISBN 9781481663182.

- ↑ Locasciulli A, Oneto R, Bacigalupo A, et al. (2007). "Outcome of patients with acquired aplastic anemia given first line bone marrow transplantation or immunosuppressive treatment in the last decade: a report from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT)". Haematologica. 92 (1): 11–8. doi:10.3324/haematol.10075. PMID 17229630.

- 1 2 Tisdale JF, Maciejewski JP, Nunez O, et al. (2002). "Late complications following treatment for severe aplastic anemia (SAA) with high-dose cyclophosphamide (Cy): follow-up of a randomized trial". Blood. 100 (13): 4668–4670. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-02-0494. PMID 12393567.

- ↑ "NIH Clinical Center: Clinical Center News, NIH Clinical Center". Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ↑ DeZern, Amy E; Brodsky, Robert A (10 January 2014). "Clinical management of aplastic anemia". Expert Review of Hematology. 4 (2): 221–230. doi:10.1586/ehm.11.11.

- ↑ Scheinberg, Phillip; Young, Neal S. (April 19, 2012). "How I treat acquired aplastic anemia". Blood. 120 (6): 1185–96. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-12-274019. PMC 3418715

. PMID 22517900. Free Text

. PMID 22517900. Free Text - ↑ Kamio, T.; Ito, E.; Ohara, A.; Kosaka, Y.; Tsuchida, M.; Yagasaki, H.; Mugishima, H.; Yabe, H.; Morimoto, A.; Ohga, S.; Muramatsu, H.; Hama, A.; Kaneko, T.; Nagasawa, M.; Kikuta, A.; Osugi, Y.; Bessho, F.; Nakahata, T.; Tsukimoto, I.; Kojima, S. (21 March 2011). "Relapse of aplastic anemia in children after immunosuppressive therapy: a report from the Japan Childhood Aplastic Anemia Study Group". Haematologica. 96 (6): 814–819. doi:10.3324/haematol.2010.035600.

In the present study, the cumulative incidence of relapse at 10 years was relatively low compared to that in other studies mainly involving adult patients. A multicenter prospective study is warranted to establish optimal therapy for children with aplastic anemia.

External links

- Aplastic Anemia & MDS International Foundation

- Mayo Clinic

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia 000554—Idiopathic aplastic anemia

- The Aplastic Anaemia Trust