Aonghus Óg of Islay

| Aonghus Óg Mac Domhnaill | |

|---|---|

| Lord of Islay | |

Aonghus Óg's name as it appears in a facsimile of correspondance between him and his feudal overlord, Edward I, King of England: "Engus de Yle".[1] | |

| Predecessor | Alasdair Óg Mac Domhnaill? |

| Spouse(s) | Áine Ní Chatháin |

|

Issue | |

| Noble family | Clann Domhnaill |

| Father | Aonghus Mór mac Domhnaill |

| Died | 1314×1318/c.1330 |

Aonghus Óg Mac Domhnaill (died 1314×1318/c.1330) was a fourteenth-century Scottish magnate and chief of Clann Domhnaill.[note 1] He was a younger son of Aonghus Mór mac Domhnaill, Lord of Islay. After the latter's apparent death, the chiefship of the kindred was assumed by Aonghus Óg's elder brother, Alasdair Óg Mac Domhnaill.

Most of the documentation regarding Aonghus Óg's career concerns his support of Edward I, King of England against supporters of John, King of Scotland. The latter's principal adherents on the western seaboard of Scotland were Clann Dubhghaill, regional rivals of Clann Domhnaill. Although there is much uncertainty concerning the Clann Domhnaill chiefship at this period in history, at some point after Alasdair Óg's apparent death at the hands of Clann Dubhghaill in 1299, Aonghus Óg seems to have taken up the chiefship as Lord of Islay.

Pressure from Clann Domhnaill and other supporters of the English Crown evidently compelled Clann Dubhghaill into coming onside with the English in the first years of the fourteenth century. However, when Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick murdered the Scottish claimant John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch in 1306, and subsequently made himself King of Scotland (as Robert I), Clann Domhnaill seems to have switched their allegiance to Robert I in an effort to gain leverage against Clann Dubhghaill. Members of Clann Domhnaill almost certainly harboured the latter in 1306, when he was doggedly pursued by adherents of the English Crown.

Following Robert I's successful consolidation of the Scottish kingship, Aonghus Óg and other members of his kindred were rewarded with extensive grants of territories formerly held by their regional opponents. According to the late fourteenth-century The Bruce, Aonghus Óg participated in the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Robert I's greatest victory over the English. It is uncertain when Aonghus Óg died. It could have been before or after the death of an unknown member of the kindred at the Battle of Faughart in 1318—a man who seems to have held the chiefship at the time. Certainly, Eóin Mac Domhnaill—Aonghus Óg's lawful son by Áine Ní Chatháin—held the chiefship by the 1330s, and became the first member of Clann Domhnaill to rule as Lord of the Isles.

Familial background

Aonghus Óg was a younger son of Aonghus Mór mac Domhnaill, Lord of Islay (died c. 1293), chief of Clann Domhnaill.[14][note 2] The latter last appears on record in 1293, when he was listed as one of the principal landholders in Argyll. At about this period, the territories possessed by the kindred comprised Kintyre, Islay, southern Jura, and perhaps Colonsay and Oronsay.[16] Clann Domhnaill was a branch of Clann Somhairle. Other branches included Clann Dubhghaill—the senior-most—and Clann Ruaidhrí.[17] Aonghus Óg's mother was a member of the Caimbéalaigh kindred (the Campbells).[18] According to Hebridean tradition preserved by the seventeenth-century Sleat History, she was a daughter of Cailéan Mór Caimbéal (died c. 1296), a leading member of the Caimbéalaigh.[19][note 3] Aonghus Óg had a sister who married Domhnall Óg Ó Domhnaill, King of Tír Chonaill (died 1281);[21] an older brother, Alasdair Óg (died 1299?),[22] who appears to have succeeded their father by 1296;[23] and another brother, Eóin Sprangach, ancestor of the Ardnamurchan branch of Clann Domhnaill.[24]

In English service against Scottish patriots

When Alexander III, King of Scotland died in 1286, his acknowledged heir was his granddaughter, Margaret (died 1290). Although this Norwegian girl was accepted by the magnates of the realm, and betrothed to the heir of Edward I, King of England (died 1307), she perished on her journey to Scotland, and her death triggered a succession crisis.[27] The leading claimants to kingship were Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale (died 1295) and John Balliol, Lord of Galloway (died 1314). By common consent, Edward I was invited to arbitrate the dispute. In 1292, John Balliol's claims were accepted, and he was duly inaugurated as King of Scotland.[28] Unfortunately for this king, his ambitious English counterpart systematically undermined his authority, and his reign lasted only about four years.[29] In 1296, after the Scottish king ratified a military treaty with France, and refused to hand over Scottish castles to Edward I's control, the English marched north and crushed the Scots at Dunbar. Edward I's forces proceeded forward virtually unopposed, whereupon Scotland fell under English control.[30]

The chief of Clann Dubhghaill in the last quarter of the thirteenth century and first decade of the next was Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill, Lord of Argyll (died 1310).[34] The wife of this pre-eminent magnate—and mother of Eóin Mac Dubhghaill (died 1316), his son and successor—was almost certainly a member of the Comyn kindred, a family closely bound to the Balliol family.[35] During the short Balliol regime, Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill had been appointed Sheriff of Lorn, a position which made him the Scottish Crown's representative throughout much of the western seaboard, including Clann Domhnaill and Caimbéalaigh territories.[36] If tradition preserved by the seventeenth-century Ane Accompt of the Genealogie of the Campbells is to be believed, Clann Dubhghaill overcame and slew Cailéan Mór in the 1290s.[37] Certainly, Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill came into bloody conflict with his Clann Domhnaill counterpart during the decade.[38]

_(seal).jpg)

This Clann Somhairle infighting appears to have stemmed from Alasdair Óg's marriage to an apparent member of Clann Dubhghaill, and seems to have concerned this woman's territorial claims.[40] Although the opposing chiefs swore to postpone their disagreement in 1292, and uphold the peace in the "isles and outlying territories", the struggle continued throughout the 1290s.[41] Clann Dubhghaill authority along the western seaboard was seriously threatened by about 1296, when Alasdair Óg was acting as Edward I's royal representative in the region.[42] Certainly, Alasdair Óg appealed to the English king regarding Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill's ravaging of Clann Domhnaill territories in 1297,[43] and may well be identical to the like-named Clann Domhnaill dynast who was recorded slain against Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill two years later.[44] If this identification is indeed correct, this could have been the point when Aonghus Óg succeeded Alasdair Óg as chief.[45] Seemingly in 1301, whilst in the service of the English Crown, Aonghus Óg inquired of Edward I as to whether he and Hugh Bisset (fl. 1301) were authorised to conduct military operations against Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill, and entreated the king on behalf of Lachlann Mac Ruaidhrí (fl. 1297–1307/1308) and (the latter's brother) Ruaidhrí Mac Ruaidhrí (died 1318?)—who were then aiding Aonghus Óg's English-aligned military forces—to grant the Clann Ruaidhrí brothers feu of their ancestral lands.[46] The fact that Aonghus Óg styled himself "of Islay" in his letter could be evidence that he was indeed acting as chief at this point.[47] Another letter, this one from Hugh to Edward I, reveals that Hugh, Eóin Mac Suibhne (fl. 1261–1301), and Aonghus Óg himself, were engaged in maritime operations against Clann Dubhghaill that year.[48][note 5]

Shift of allegiance to the Bruce cause

_crop.png)

In February 1306, Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick (died 1329), a claimant to the Scottish throne, murdered his chief rival to the kingship, John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch.[51] Although the former seized the throne (as Robert I) by March, the English Crown immediately struck back, defeating his forces in June. By September, Robert I was a fugitive, and seems to have escaped into the Hebrides.[52] There is no certain record of Aonghus Óg between 1301 and 1306.[53] If the fourteenth-century historian John Barbour (died 1395) is to be believed, however, Aonghus Óg played an instrumental part in Robert I's survival. Specifically, John Barbour's The Bruce relates that, after Robert I was defeated at Methven and Dalry in the summer of 1306, the king fled into the mountains and made for the coast of Kintyre, where he was protected by Aonghus Óg himself.[54] Although the The Bruce maintains that Aonghus Óg harboured the king at Dunaverty Castle,[55] contemporary evidence reveals that Robert I's men were already in possession of the fortress by March, having acquired it from a certain Maol Coluim (died 1307?).[56] In fact, in the immediate aftermath of John Comyn's murder, Robert I secured control of several western fortresses (including that of Dunaverty), seemingly in an effort to keep a lane open for military assistance from Ireland or the Hebrides.[57]

According to The Bruce, Robert I stayed at the castle for three days before fleeing to Rathlin Island.[60] There is reason to suspect that John Barbour conflated his account of the king's landing on the island and his flight to the castle. These incidents could therefore refer to one episode in which the king fled Kintyre to a Clann Domhnaill castle on Islay—perhaps Dunyvaig Castle—the next northern-most island.[61][note 6] Certainly, contemporary sources reveal that Dunaverty Castle succumbed to an English-backed siege in September.[64] Quite where Robert I fled to after leaving Kinytre is uncertain. He could have spent time in the Hebrides, Ulster, or Orkney.[65] Certainly, the fourteenth-century Gesta Annalia II states that the king was assisted by Cairistíona Nic Ruaidhrí (fl. 1290–1318)—a woman with Hebridean connections[66]—and it is possible that the king indeed set sail for a Clann Ruaidhrí or Clann Domhnaill island.[67] Certainly, Edward I himself thought that Robert I was hidden somewhere amongst the "Isles on the Scottish coast".[68][note 7]

The catalyst behind Clann Domhnaill's shift of allegiance from Edward I to Robert I likely lies in local Hebridean politics rather than Scottish patriotism.[71] Whilst Edward I's destruction of the Balliol regime in 1296 resulted in Clann Dubhghaill finding itself out of favour with the English regime, Clann Domhnaill seems to have sided with the English Crown in an effort to earn royal support in its localised power struggle with Clann Dubhghaill.[72] To the leading kindreds on the western seaboard, internecine rivalries appear to have been more of a concern than the greater war over the Scottish Crown.[73] Aonghus Óg's documented service to the English Crown in the years after Alasdair Óg's apparent death was almost certainly undertaken in the context of pursuing his kindred's struggle against Clann Dubhghaill.[53] Pressure from Clann Domhnaill and other supporters of the English Crown evidently compelled Clann Dubhghaill into coming onside with the English in the first years of the fourteenth century.[74] Whilst Robert I's subsequent murder of John Comyn undoubtedly galvanised Clann Dubhghaill's new-found alignment with Edward I, it also precipitated Clann Domhnaill's realignment of support from the English Crown to the Bruce cause.[75][note 8] Although Edward I ordered Hugh and John Menteith (died 1323?) to sweep the western seaboard with their fleets in 1307,[77] the evanescent Scottish monarch remained at large, seemingly harboured by Clann Domhnaill and Clann Ruaidhrí.[78]

Rewarded service to the Scottish Crown, and a contested chiefship

In 1307, at about the time of Edward I's death in July, Robert I mounted his remarkable return to power, first striking into Carrick in about February.[80] By 1309, Robert I's opponents had been largely overcome, and he held his first parliament as king.[81] Clann Domhnaill clearly benefited from their support of the Bruce cause. Although no royal charters associated with the kindred exist from this period, there are seventeenth-century charter indices that note several undated royal grants.[82] For instance, Aonghus Óg was granted the former Comyn lordship of Lochaber and the adjacent regions of Ardnamurchan, Morvern, Duror, and Glencoe;[83] whilst a certain Alasdair Mac Domhnaill received the former Clann Dubhghaill islands of Mull and Tiree.[84]

Although the aforesaid indices fail to note any Clann Domhnaill grants concerning Islay and Kintyre it is not inconceivable that the kindred received grants of these territories as well.[85] Later in the fourteenth century, Aonghus Óg's son, Eóin Mac Domhnaill, was granted the territories of Ardnamurchan, Colonsay, Gigha, Glencoe, Jura, Kintyre, Knapdale, Lewis, Lochaber, Morvern, Mull, and Skye. It is possible that the basis for many of these grants laid in the kindred's military support of the Bruce cause, and stemmed from concessions grained from the embattled king in about 1306.[86] If this was indeed the case, the fact that Robert I later granted a significant portion of these territories (Lochaber, Kintyre, Skye, and lands in Argyll) to other magnates suggests that his conceivable concessions to Clann Domhnaill may have been undertaken with some reluctance.[87]

There is reason to suspect that the Clann Domhnaill chiefship was contested during this period.[90] For example, the aforesaid grants to Aonghus Óg and Alasdair Mac Domhnaill—a man whose identity is uncertain—could be evidence that these two were competitors.[91] Furthermore, another apparent claimant to the chiefship, a certain Domhnall styled "of Islay"—whose identity is likewise uncertain—was present at the aforesaid parliament of 1309.[92][note 9] Furthermore, The Bruce states that when Robert I fled to Dunaverty Castle in 1306 he was fearful of treason during his stay there.[95][note 10] Although this source further claims that Aonghus Óg lent the king assistance at the castle there may be reason to question this identification.[97] The Bruce was certainly influenced by later political realitites,[98] and was composed during the reign of Robert II, King of Scotland (1371–1390), the father-in-law of Aonghus Óg's aforesaid son.[99] The fact that this son ruled as chief when the poem was composed could account for the remarkably favourable light in which Aonghus Óg is portrayed.[100] Furthermore, the claim that Aonghus Óg was Lord of Kintyre at the time of the aforesaid Dunaverty episode could be a result of the fact that, by the time the The Bruce was composed, Aonghus Óg's aforesaid son was married to a daughter of the Robert II, and had gained this contested lordship by way of her tocher.[101][note 11]

Participation in the Battle of Bannockburn

In about November 1313, Robert I declared that his opponents had one year to come into his peace or suffer permanent disinheritance. Seemingly in consequence of this declaration, Edward II announced a massive invasion of Scotland.[105] On 23–24 June, the English and Scottish royal armies clashed near Stirling at what became known as the Battle of Bannockburn. Although there are numerous accounts of the battle, one of the most important sources is The Bruce,[4] which specifies that the Scottish army was divided into several battalions. According to this source, the king's battalion was composed of men from Carrick, Argyll, Kintyre, the Hebrides, and the Scottish Lowlands.[106][note 12] Although the size of the opposing armies is uncertain,[108] the Scottish force was undoubtedly smaller than that of English,[4] and may well have numbered somewhere between five thousand[63] and ten thousand.[109] The battle resulted in one of the worst military defeats suffered by the English.[110] Amongst the Hebridean contingent, the The Bruce notes Aonghus Óg himself.[111] According to this source, the king's battalion played a significant part in the conflict: for although it had hung back during the onset of hostilities, the battalion engaged the English at critical point in the fray.[112] Whatever the case, just as with the aforesaid episode at Dunaverty, John Barbour's association of Aonghus Óg with Bannockburn could well be influenced by later political realities.[113]

Clann Domhnaill's part in the Bruce campaign in Ireland

Aonghus Óg—or at least a close relative—may have played a part in the Scottish Crown's later campaigning against the Anglo-Irish in Ireland.[115] In 1315, Robert I's younger brother, Edward Bruce, Earl of Carrick (died 1318), launched an invasion of Ireland and claimed the high-kingship of Ireland. For three years, the Scots and their Irish allies campaigned on the island against the Anglo-Irish and their allies.[116] Although every other pitched-battle between the Scots and the Anglo-Irish resulted in a Scottish victory,[117] the utter catastrophe at the Battle of Faughart cost Edward his life and brought an end to the Bruce regime in Ireland.[118] According to the sixteenth-century Annals of Loch Cé, a certain "Mac Ruaidhri ri Innsi Gall" and a "Mac Domnaill, ri Oirir Gaidheal" were slain in the onslaught.[119] This source is mirrored by several other Irish annals including the fifteenth–sixteenth-century Annals of Connacht,[120] the seventeenth-century Annals of the Four Masters,[121] the fifteenth–sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster,[122] and the seventeenth-century Annals of Clonmacnoise.[123][note 13] The precise identities of these men are unknown for certain, although they could well have been the heads of Clann Ruaidhrí and Clann Domhnaill.[125] Whilst the slain member of Clann Ruaidhrí seems to have been the aforesaid Ruaidhrí,[126] the identity of the Clann Domhnaill dynast is much less certain. He could have been Alasdair Óg (if this man was not the one who had been killed in 1299),[127] or perhaps a son of Alasdair Óg.[128] Another possibility is that he was Aonghus Óg himself,[115] or perhaps a son of his.[129] An after-effect of the continued support of Clann Domhnaill and Clann Ruaidhrí to the Bruce cause was the destruction of their regional rivals like Clann Dubhghaill.[130] In fact, the albeit exaggerated title "King of Argyll" accorded to the aforesaid slain Clann Domhnaill dynast in many of these annal-entries exemplifies the catastrophic effect that the rise of the Bruce regime had on its opponents like Clann Dubhghaill.[131] By the mid-part of the century, Clann Domhnaill, under the leadership of Aonghus Óg's aforesaid son, was undoubtably the most powerful branch of Clann Somhairle.[130]

Death and descendants

.jpg)

Aonghus Óg seems to have died at some point after the Battle of Bannockburn—notwithstanding the Hebridean tradition preserved by the eighteenth-century Book of Clanranald and the Sleat History that dates his death to about 1300.[133] One possibility is that he passed away between 1314 and 1318.[134] This could well have been the case if the slain Clann Domhnaill chieftain at Faughart was indeed his son and successor.[135] On the other hand, it is not impossible that Aonghus Óg lived as late as about 1330, after which the Clann Domhnaill lordship seems to have taken up by his aforesaid son, Eóin Mac Domhnaill.[136] In 1336, the latter was the first member of Clann Domhnaill to bear the title dominus insularum ("Lord of the Isles").[137] The political situation in the Hebrides is murky between this man's accession and the disaster at Faughart,[138] and it is possible that an after-effect of the defeat was a period of Clann Ruaidhrí dominance in the region.[139] In 1325, a certain "Roderici de Ylay" suffered the forfeiture of his possessions by Robert I.[140] Although this record could refer to a member of Clann Ruaidhrí[141]—perhaps Raghnall Mac Ruaidhrí (died 1346)[142]—another possibility is that the individual actually refers to a member of Clann Domhnaill[143]—perhaps a son of either Alasdair Óg or Aonghus Óg.[144] If Aonghus Óg was still alive in 1325, he would have witnessed Robert I's apparent show of force into Argyll within the same year. Although Aonghus Óg's tenure as chief is remarkable in regard to his close support of the Bruce cause, the later career of Eóin Mac Domhnaill saw a remarkable cooling of relations with the Bruce regime—a distancing which may well have contributed to the latter's adoption of the title "Lord of the Isles".[145][note 14]

Aonghus Óg married Áine Ní Chatháin, an Irish woman from Ulster.[150] According to the Sleat History, Áine Ní Chatháin's tocher consisted of one hundred and forty men from each surname that dwelt in the territory of her father, Cú Maighe na nGall Ó Catháin,[151] whilst the Book of Clanranald numbers the men at eighty.[152] The Uí Catháin of Ciannachta were a major branch of the Uí Néill kindred,[153] and the léine chneas or "train of followers" that is said to have accompanied Áine Ní Chatháin is the most remarkable retinue have arrived in marriage from Ireland in Scottish tradition.[154] The tocher itself appears similar to a historical one dating almost a century earlier, when a Clann Ruaidhrí bride brought over one hundred and sixty warriors to her Irish husband.[155] The tradition of the marriage itself is corroborated by the record of an English safe-conduct instrument granted to Áine Ní Chatháin, identified as the mother of Aonghus Óg's aforesaid son, in 1338.[156] At a later date, Áine Ní Chatháin appears to have remarried a member of Clann Aodha Buidhe,[157] a branch of the Ó Néill kindred.[158][note 16]

Aonghus Óg and Áine Ní Chatháin were the parents of the aforesaid Eóin Mac Domhnaill.[162] Another child of the couple may be the Áine Nic Domhnaill noted in the Clann Lachlainn pedigree preserved by MS 1467. This late mediaeval source reveals that this woman was the wife Lachlann Óg Mac Lachlainn, and mother of his son, Eóin Mac Lachlainn.[163] Whatever the case, a certain daughter of Aonghus Óg was Máire, a woman who married William III, Earl of Ross (died 1372).[164] Aonghus Óg appears to have also had another son named Eóin,[165] a man from whom descended the Glencoe branch of Clann Domhnaill.[166]

According to early modern Kincara manuscript, an ancestor of Clann Mhic an Tóisigh named Fearchar married a daughter of Aonghus Óg named "Moram". The fact that Fearchar is supposed to have died in 1274, however, suggests that this source has conflated Aonghus Óg and Aonghus Mór.[167] According to the Sleat History, an illegitimate daughter of Aonghus Mór was the mother of an early ancestor of Clann Mhic an Tóisigh. This chieftain is stated to have fled to Aonghus Mór whilst on the run for committing manslaughter; and after fathering an illegitimate son—the ancestor of later Clann Mhic an Tóisigh chiefs—the chieftain is stated to have campaigned with Edward Bruce in Ireland where he was slain himself. The Sleat History also claims that the slain man's young son was brought up in Clann Domhnaill territory and endowed by the kindred with lands in Lochaber and Moray.[168] Whatever the case, there is no solid evidence of Clann Mhic an Tóisigh in the Lochaber region before the reign of Robert II.[169]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Aonghus Óg of Islay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Since the 1990s, academics have accorded Aonghus Óg various patronymic names in English secondary sources: Aengus Óg Mac Domnaill,[2] Aengus Óg MacDomhnaill,[3] Angus Macdonald,[4] Angus MacDonald,[5] Angus Og mac Donald,[6] Angus Og macDonald,[6] Angus Óg MacDonald,[7] Angus Og Macdonald,[8] Angus Og MacDonald,[9] Aonghas Óg MacDhomhnaill,[10] Aonghas Óg MacDòmhnaill,[11] Aonghus Óg Mac Domhnaill,[12] and Aonghus Óg MacDomnaill.[13]

- ↑ The Gaelic Óg and Mór mean "young" and "big" respectively.[15]

- ↑ The indentity of this woman is unsupported by traditional genealogies of the Caimbéalaigh.[20]

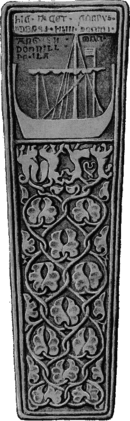

- ↑ The coat of arms is blazoned: or, a galley sable with dragon heads at prow and stern and flag flying gules, charged on the hull with four portholes argent.[32] The coat of arms corresponds to the seal of Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill.[33] Since the galley was a symbol of Clann Dubhghaill and seemingly Raghnall mac Somhairle (died 1191/1192–c. 1210/1227)—ancestor of Clann Ruaidhrí and Clann Domhnaill—it is conceivable that it was also a symbol of the eponymous ancestor of Clann Somhairle, Somhairle mac Giolla Brighde (died 1164).[26]

- ↑ Although these letters of Aonghus Óg and Hugh are generally assumed to date to 1301, another letter associated with them concerns the continued English service of Hugh and Eóin Mac Suibhne. The fact that this piece of correspondence identifies John Menteith as an opponent of the English Crown suggests that all three may instead date to 1310.[49]

- ↑ The Bruce declares that, when Robert I landed on Rathlin, the inhabitants fled to a "rycht stalwart castell". The fact that no such castle existed, combined with the claim that the islanders promised to render daily provisions for three hundred of the king's supports, suggests that the text refers to a larger island in the Hebrides.[62] At the time, the lord of the island was the aforesaid Hugh.[63]

- ↑ The entire Dunaverty episode is absent from the account of Robert I's flight recorded by Gesta Annalia II.[69]

- ↑ John Comyn may well have been a first cousin of Eóin Mac Dubhghaill.[76]

- ↑ Domhnall also witnessed an undated charter of the king.[93] He is further attested in records revealing that Eóin Mac Dubhghaill was commissioned to bring him—and an apparent brother of Domhnall—into the peace of Edward II, King of England (died 1327) in March 1313/1314 and March 1314/1315.[94]

- ↑ The fact that the less than non-partisan Sleat History declares that Aonghus Óg was "always a follower of King Robert Bruce in all his wars" could be evidence of insecurity on the historian's part rather than an accurate reflection of Aonghus Óg's allegiance.[96]

- ↑ Earlier, during the tenure of Alasdair Óg, Clann Domhnaill appears to have vied for control of swathes of Kintyre with the aforesaid Maol Coluim.[102] This man appears to be identical to the Lord of Kintyre who was slain in 1307 campaigning with two of Robert I's brothers in Galloway.[103]

- ↑ The composition of the other Scottish battalions is unrecorded and uncertain. Although The Bruce states that there were four Scottish battalions, other sources—such as the fourteenth-century Vita Edwardi Secundi, the fourteenth-century Lanercost Chronicle, and the fourteenth-century Scalacronica—state that there were only three.[107]

- ↑ The Annals of Clonmacnoise exists only in a early modern translation and gives: "mcRory king of the islands and mcDonnell prince of the Irish of Scotland".[123] The eleventh–fourteenth-century Annals of Inisfallen also note the fall of Edward Bruce and a certain "Alexander M", a man who could be identical to the Clann Domhnaill dynast referred to by the aforesaid sources.[124]

- ↑ The adoption of the title further evidences the kindred's new-found dominance over the other branches of Clann Somhairle.[146]

- ↑ The stone appears to have been engraved: "HIC•[IA]CET•CO[R]PVS•[EN]G[VS]II•[FI]LII•DOMINI/•ENGVSII•MAC•/DOMNILL•/DE YLE•". This has been translated to: "Here lies the body of Angusius, son of Lord Angusius MacDonald of Islay".[148] One possibility is that the stone commemorates a son of the fifteenth-century claimant to the lordship of the Isles, Aonghus Óg Mac Domhnaill (died c. 1490).[149]

- ↑ Although Áine Ní Chatháin is not named by the Book of Clanranald, and accorded the name "Margaret" by the Sleat History, she is named "Any" by another early modern account of the marriage.[159] One of the Scottish families that may have originated from the retinue was the Mac Beathadh medical kindred.[160] In fact, the earliest member of this family on record was a physician of Robert I, which may have bearing upon the king's close association with Clann Domhnaill.[161]

- ↑ Giolla Easbaig is the first member of the Caimbéalaigh to appear in contemporary sources.[172]

- ↑ Another possibility is that Giolla Easbaig's wife (and Cailéan Mór's mother) was one of the four known daughters of Niall, Earl of Carrick. If correct, it would mean that Cailéan Mór was a first cousin of Robert I.[174]

Citations

- 1 2 List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 197; Stevenson (1870) p. 436 § 615; Bain (1884) p. 320 § 1254; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 80–81; PoMS, H3/31/0 (n.d.c); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84286 (n.d.).

- ↑ Duffy (2002).

- ↑ Boardman, S (2007).

- 1 2 3 Gledhill (2015).

- ↑ Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004).

- 1 2 Roberts (1999).

- ↑ Cameron (2014); McNamee (2012a); McNamee (2012b); Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004); Sellar (2000); McDonald (1997).

- ↑ Daniels (2013).

- ↑ Penman, M (2014); Macdougall (2001); Woolf (2001); Campbell of Airds (2000); Roberts (1999); Sellar; Maclean (1999).

- ↑ Bateman; McLeod (2007).

- ↑ MacDonald, IG (2014).

- ↑ McLeod (2005).

- ↑ Macdougall (2001); Woolf (2001).

- ↑ McDonald (2004) p. 186; Sellar (2000) p. 194 tab ii; McDonald (1997) pp. 130, 141; Barrow (1988) p. 163.

- ↑ Hickey (2011) p. 182.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 130.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) pp. 128–131.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 66; Roberts (1999) p. 131; Maclean-Bristol (1995) p. 168; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 281.

- ↑ Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 51; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 281; Macphail (1914) p. 17.

- ↑ Munro; Munro (1986) p. 281.

- ↑ Duffy (2007) p. 16; Duffy (2002) p. 61; Sellar (2000) p. 194 tab ii; Walsh (1938) p. 377.

- ↑ Sellar (2000) p. 194 tab ii; McDonald (1997) pp. 130, 141; Barrow (1988) p. 163.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 159.

- ↑ Addyman; Oram (2012); Coira (2012) pp. 76 tab. 3.3, 334 n. 71; Caldwell, D (2008) pp. 49, 52, 70; Roberts (1999) p. 99 fig. 5.2.

- ↑ McDonald (1995) pp. 131–132, 132 n. 12; Rixson (1982) pl. 3a; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 102–103; Bain (1884) p. 559 § 631; Laing, H (1850) p. 79 § 450.

- 1 2 Campbell of Airds (2014) pp. 202–203.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 160.

- ↑ Stell (2005); McDonald (1997) p. 160.

- ↑ Stell (2005); McDonald (1997) pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Stell (2005).

- ↑ Campbell of Airds (2014) p. 204; McAndrew (2006) p. 66; McAndrew (1999) p. 693; McAndrew (1992); The Balliol Roll (n.d.).

- ↑ McAndrew (2006) p. 66; The Balliol Roll (n.d.).

- ↑ McAndrew (2006) p. 66; McAndrew (1999) p. 693; McAndrew (1992).

- ↑ Sellar (2000) pp. 208–215.

- ↑ Brown (2004) p. 256; Sellar (2004a); Sellar (2004b); Sellar (2000) pp. 209 tab iii, 210; McDonald (1997) p. 162.

- ↑ Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 49–50; Young; Stead (2010) p. 40; Brown (2004) p. 258; Sellar (2000) p. 212; McDonald (1997) pp. 131–134, 163.

- ↑ Sellar (2004a); Sellar (2004b); Sellar (2000) p. 212, 212 n. 130; Macphail (1916) p. 85, 85 n. 1.

- ↑ Sellar (2004a); Sellar (2000) p. 212.

- ↑ McDonald (1995) p. 132; Rixson (1982) pp. 128, 219 n. 2, pl. 3b; Macdonald, WR (1904) p. 227 § 1793; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 88–89; Laing, H (1866) p. 91 § 536.

- ↑ Watson (2013) ch. 2; McDonald (2006) p. 78; Brown (2004) p. 258, 258 n. 1; Sellar (2000) p. 212, 212 n. 128; McDonald (1997) pp. 163–164, 171; Barrow (1988) pp. 57–58; Lamont (1981) pp. 160, 162–163; Rymer; Sanderson (1816) p. 761; Bain (1884) p. 145 § 621; Rotuli Scotiæ' (1814) p. 21; PoMS, H3/33/0 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 80039 (n.d.).

- ↑ Brown (2004) p. 258; Sellar (2000) p. 212; Barrow (1988) pp. 57–58; Bain (1884) p. 145 §§ 622–623; Rymer; Sanderson (1816) p. 761; PoMS, H3/31/0 (n.d.a); PoMS, H3/31/0 (n.d.b); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 80065 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 80071 (n.d.).

- ↑ Watson (2013) ch. 2; McNamee (2012a) ch. 2; Young; Stead (2010) pp. 50–51; Brown (2004) p. 259; McDonald (1997) p. 166; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 217; Bain (1884) p. 225 § 853; Stevenson (1870) pp. 187–188 § 444; Rotuli Scotiæ' (1814) pp. 22–23, 40; PoMS, H3/0/0 (n.d.a); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 83146 (n.d.).

- ↑ Watson (2013) ch. 2, ch. 2 n. 52; Fisher (2005) p. 93; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 60; Sellar (2000) p. 212; McDonald (1997) pp. 154, 165, 190; Barrow (1988) pp. 107, 347 n. 104; Rixson (1982) pp. 13–16, 208 nn. 2, 4, 208 n. 6; List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 193; Bain (1884) pp. 235–236 §§ 903–904; Stevenson (1870) pp. 187–188 § 444, 189–191 § 445; PoMS, H3/0/0 (n.d.a); PoMS, H3/0/0 (n.d.b); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 83146 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84392 (n.d.).

- ↑ Sellar (2016) p. 104; Penman, MA (2014) p. 65, 65 n. 7; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 1299.3; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 1299.3; McNamee (2012a) ch. 2; Annála Connacht (2011a) § 1299.2; Annála Connacht (2011b) § 1299.2; Annals of Loch Cé (2008) § 1299.1; Annala Uladh (2005) § 1295.1; Annals of Loch Cé (2005) § 1299.1; Brown (2004) p. 260; Sellar (2004a); Annala Uladh (2003) § 1295.1; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 61; Sellar (2000) pp. 212–213; McDonald (1997) pp. 168–169, 168–169 n. 36; Barrow (1988) p. 163; Lamont (1981) p. 168.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) ch. 2; McDonald (1997) p. 169.

- ↑ Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 59; Cameron (2014) p. 153; Barrow (2003) p. 347; McDonald (1997) pp. 167, 169, 190–191; Barrow (1988) pp. 168, 347 n. 104; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 281; Lamont (1981) pp. 161, 164; Barrow (1973) p. 381; List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 197; Stevenson (1870) p. 436 § 615; Bain (1884) p. 320 § 1254; PoMS, H3/31/0 (n.d.c); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84286 (n.d.).

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 169.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 167; List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 197; Reid (1960) pp. 10–11; Stevenson (1870) p. 435 § 614; Bain (1884) p. 320 § 1253; PoMS, H3/90/11 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84282 (n.d.).

- ↑ Nicholls (2007) p. 92, 92 n. 47; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 281; Lamont (1981) p. 162; Stevenson (1870) p. 437 § 616; Bain (1884) p. 320 § 1255; PoMS, H3/381/0 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84292 (n.d.).

- ↑ Collard (2007) pp. 2, 10 fig. 8.

- ↑ Young; Stead (2010) p. 80; Barrow (2008); Young (2004); Boardman, S (2001); McDonald (1997) p. 169.

- ↑ Barrow (2008); McDonald (1997) pp. 170–174.

- 1 2 McDonald (1997) p. 171.

- ↑ McNamee (2012b) ch. 1; McDonald (2006) p. 78; Duncan (2007) pp. 142–147; McDonald (1997) pp. 171–174; Mackenzie (1909) pp. 52–54; Eyre-Todd (1907) p. 50.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 68; McNamee (2012a) ch. 5; McNamee (2012b) ch. 1; McNamee (2012b) ch. 1; Duncan (2007) pp. 142–147; McDonald (2006) p. 78; Lamont (1981) p. 164, 164 n. 3; Mackenzie (1909) pp. 52–54; Eyre-Todd (1907) p. 50.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) ch. 5; McNamee (2012b) chs. 1–2; Duncan (2007) p. 144 n. 659–78; Barrow (1988) pp. 149, 355 n. 9; Dunbar; Duncan (1971) pp. 4–5; Riley (1873) pp. 347–353; PoMS, H5/3/0 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 86691 (n.d.).

- ↑ McNamee (2012b) ch. 1; Duncan (1992) p. 136.

- ↑ Duncan (2007) p. 148 n. 725–762.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) pp. 68–69; Duncan (2007) p. 148 n. 725–762.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) ch. 5; McNamee (2012b) chs. 1–2; Young; Stead (2010) p. 90; Duncan (2007) pp. 144–145, 144–145 n. 677; McDonald (1997) p. 173.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) pp. 68–69; McNamee (2012a) ch. 5; McNamee (2012b) ch. 2; Duncan (2007) pp. 144 n. 659–678, 145 n. 680, 148 n. 725–762; McDonald (1997) p. 173 n. 49.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) ch. 5; Duncan (2007) pp. 148–149; Mackenzie (1909) p. 55; Eyre-Todd (1907) p. 51–51.

- 1 2 McNamee (2012b) ch. 2.

- ↑ McNamee (2012b) chs. introduction, 1; Prestwich (1988) p. 507; List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 209; Bain (1888) p. 488 § 5; Bain (1884) p. 491 §§ 1833, 1834; Simpson; Galbraith (n.d.) pp. 195 § 457, 196 § 465.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 103; McNamee (2012b) chs. introduction, 1, 2; Young; Stead (2010) pp. 90–92; Boardman, S (2001); McDonald (1997) p. 174; Barrow (1988) pp. 166–171.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 104, 359 n. 82; Young; Stead (2010) p. 92; Boardman, S (2006) p. 55 n. 61; McDonald (2006) p. 79; Barrow (2003) p. 347; Duffy (2002) p. 60; McDonald (1997) pp. 174, 189, 196; Barrow (1988) p. 170; Barrow (1973) pp. 380–381; Skene (1874) p. 335; Skene (1871) p. 343.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 103.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 104; Bain (1884) pp. 501–502 § 1888, 504 §§ 1893, 1895, 1896.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2007) p. 105.

- ↑ Macdonald, WR (1904) p. 247 § 1950; Fraser (1888) pp. 455, 461 fig. 3; Laing, H (1866) p. 120 § 722.

- ↑ McDonald (2006) p. 78; Brown (2004) pp. 261–262; Roberts (1999) p. 131; McDonald (1997) pp. 171–172.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) ch. 2; Young; Stead (2010) p. 42.

- ↑ Brown (2004) p. 260.

- ↑ Watson (2013) ch. 4; McNamee (2012a) ch. 2; Brown (2004) pp. 260–261; McDonald (1997) p. 171.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) chs. 2, 5; McNamee (2012b) ch. 2; Grant (2006) p. 371; Brown (2004) pp. 261–262; Oram (2004) p. 123; McDonald (1997) pp. 171–172; Barrow (1988) pp. 163, 291; Lamont (1981) p. 163.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) chs. 5, notes on sources n. 5.

- ↑ McNamee (2012b) ch. 2; Brown (2004) p. 262; Watson (2004); Barrow (1988) pp. 168–169; Rixson (1982) p. 20; Reid (1960) p. 16; Calendar of the Close Rolls (1908) p. 482; Sweetman; Handcock (1886) p. 183 § 627; Bain (1884) pp. 501–502 § 1888, 516 § 1941.

- 1 2 Brown (2004) p. 262.

- ↑ Birch (1905) p. 135 pl. 20.

- ↑ Young; Stead (2010) pp. 92–93; Barrow (2008); McDonald (1997) pp. 174–175; Barrow (1988) pp. 170–173.

- ↑ Barrow (2008).

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 66.

- ↑ MacDonald, IG (2014) p. 48 n. 136; Penman, M (2014) p. 102; Penman, MA (2014) p. 66; Daniels (2013) p. 25; McNamee (2012a) ch. 10; Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004); Brown (2004) p. 263; Oram (2004) p. 124; Duffy (2002) p. 62; Roberts (1999) p. 143; McDonald (1997) p. 184, 184 n. 104; Barrow (1988) p. 291; Lamont (1981) p. 168; Thomson (1912) p. 512 §§ 56–58.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 102; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 67–68; Brown (2004) p. 263; McDonald (1997) p. 184, 184 n. 104; Duffy (1991) p. 312; Barrow (1988) p. 291; Lamont (1981) p. 168; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203; Thomson (1912) p. 553 § 653.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) ch. 10; Barrow (1988) p. 291.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) pp. 66–67; Thomson (1912) pp. 482 § 114; 561 § 752; Bain (1887) pp. 213–214 § 1182; Robertson (1798) p. 48.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) pp. 66–67.

- ↑ MacDonald; MacDonald (1900) pp. 82–83.

- ↑ MacDonald; MacDonald (1900) pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Duncan (2007) p. 148 n. 725–762; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 102; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Sellar (2016) p. 104; Penman, M (2014) p. 102; Penman, MA (2014) p. 68; Barrow (1988) pp. 163, 185–186, 360 n. 124; Lamont (1981) pp. 165, 167; RPS, 1309/1 (n.d.a); RPS, 1309/1 (n.d.b).

- ↑ Barrow (1988) pp. 163, 360 n. 124; Lamont (1981) pp. 165, 167; Liber Sancte Marie (1836) pp. 340–341 § 376.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 70; Sellar; Maclean (1999) p. 7; Duffy (1991) p. 312; Barrow (1988) pp. 163, 360 n. 124; Lamont (1981) pp. 165–166; List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 209; Bain (1888) p. 377 § 1822; Rotuli Scotiæ (1814) pp. 121, 139; PoMS, H1/27/0 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 88734 (n.d.).

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 102–103; Penman, MA (2014) p. 68; McNamee (2012a) ch. 5; McNamee (2012b) ch. 1; Duncan (2007) p. 144–145; Mackenzie (1909) p. 53; Eyre-Todd (1907) p. 50.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 358 n. 68; Penman, MA (2014) p. 68 n. 20; McDonald (1997) p. 159; Macphail (1914) p. 14.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 68; Duncan (2007) p. 148 n. 725–762.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) pp. 68, 69 n. 21; Cornell (2009) p. xi; Boardman, S (2007) pp. 105–106, 105 nn. 65, 66.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 69 n. 21.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) pp. 68, 69 n. 21; Duncan (2007) p. 148 n. 725–762.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 102; Penman, MA (2014) p. 66; Boardman, S (2007) p. 105 n. 65; Duncan (2007) pp. 144–145; Mackenzie (1909) p. 53; Eyre-Todd (1907) p. 50.

- ↑ Duncan (2007) p. 144 n. 659–78; Barrow (1988) pp. 149, 355 n. 10, 337 n. 11; Dunbar; Duncan (1971) pp. 3–5, 16–17; Bain (1884) p. 225 § 853; Rotuli Scotiæ' (1814) pp. 22–23; Simpson; Galbraith (n.d.) p. 152 § 152; PoMS, H3/0/0 (n.d.c); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 88525 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 88534 (n.d.).

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 104–105; Duncan (2007) p. 152 n. 36–38.

- ↑ MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 96–97.

- ↑ McNamee (2012b) ch. 2, 2 n. 136; Duncan (1992) pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Gledhill (2015); Penman, MA (2014) p. 69; McNamee (2012b) ch. 2 n. 28; Brown (2008) p. 118; Duncan (2007) pp. 421–423; McDonald (1997) p. 183; Barrow (1988) p. 210; Mackenzie (1909) p. 201; Eyre-Todd (1907) p. 191.

- ↑ McNamee (2012b) ch. 2, 2 n. 158; Brown (2008) p. 118.

- ↑ Gledhill (2015); King (2015).

- ↑ Gledhill (2015); McNamee (2012b) ch. 2; Barrow (2008); Barrow (1988) pp. 208–209.

- ↑ King (2015).

- ↑ Brown (2008) p. 118; Boardman, S (2007) p. 105; Duncan (2007) p. 421; McDonald (1997) pp. 183–184; Mackenzie (1909) p. 201; Eyre-Todd (1907) p. 191.

- ↑ Duncan (2007) pp. 486–487; McDonald (1997) p. 183; Barrow (1988) pp. 227–228; Mackenzie (1909) pp. 229–231; Eyre-Todd (1907) pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2007) p. 105, 105 n. 66.

- ↑ The Balliol Roll (n.d.).

- 1 2 Brown (2008) p. 153; Penman, MA (2014) p. 71; Brown (2004) p. 265.

- ↑ Duncan (2010); Young; Stead (2010) pp. 144, 146–147; Brown (2008) pp. 143–153; Duffy (2005); Brown (2004) pp. 264–265; Frame (1998) pp. 71–98; Lydon (1992) pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Lydon (1992) p. 3.

- ↑ Duncan (2010); Duffy (2005).

- ↑ Annals of Loch Cé (2008) § 1318.7; Annals of Loch Cé (2005) § 1318.7; Caldwell, DH (2004) p. 72; McDonald (1997) p. 191; Barrow (1988) p. 377 n. 103.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 71; Annála Connacht (2011a) § 1318.8; Annála Connacht (2011b) § 1318.8; McLeod (2002) p. 31 n. 24; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 77; Davies (2000) p. 175 n. 14; Duffy (1998) p. 79; Dundalk (n.d.); The Annals of Connacht, p. 253 (n.d.).

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 1318.5; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 1318.5; McLeod (2002) p. 31 n. 24; Duffy (1998) pp. 79, 102.

- ↑ Annala Uladh (2005) § 1315.5; Boardman, SI (2004); Sellar (2000) p. 217 n. 155; Annala Uladh (2003) § 1315.5; McLeod (2002) p. 31 n. 24; Roberts (1999) p. 181; Bannerman (1998) p. 25; Duffy (1998) p. 79; Lydon (1992) p. 5; Barrow (1988) pp. 361 n. 15, 377 n. 103; Lamont (1981) p. 166; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 205 n. 9; Dundalk (n.d.); Mac Ruaidhri, King of the Hebrides (n.d.); AU, 1315 (n.d.).

- 1 2 McLeod (2002) p. 31 n. 24; Barrow (1988) p. 377 n. 103; Murphy (1896) p. 281.

- ↑ Sellar (2016) p. 104; Penman, MA (2014) p. 71; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1318.4; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1318.4; McDonald (1997) pp. 186–187, 187 n. 112; Duffy (1991) p. 312; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ Duffy (2002) p. 61, 195 n. 64; McQueen (2002) p. 287 n. 18; Duffy (1991) p. 312; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) p. 94; Boardman, S (2006) pp. 45–46; Brown (2004) p. 265; Boardman, SI (2004); Caldwell, DH (2004) p. 72; Duffy (2002) pp. 61, 195 n. 64; Roberts (1999) pp. 144, 181; Barrow (1988) p. 377 n. 103; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) pp. 65 n. 7, 70–71; Duffy (2002) p. 195 n. 64; Duffy (1991) p. 312, 312 n. 52.

- ↑ Cameron (2014) p. 153; Penman, MA (2014) p. 71; Barrow (1988) p. 361 n. 15.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 71; McNamee (2012a) ch. genealogical tables tab. 6; Roberts (1999) p. 181; Duffy (1991) p. 312 n. 52; McDonald (1997) pp. 186–187; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- 1 2 Brown; Boardman (2005) pp. 73–74; Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004).

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) ch. 8; McNamee (2012b) ch. 5.

- ↑ Laing, D (1878) pl. 50; Sir David Lindsay's Armorial (n.d.).

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 186; Macphail (1914) p. 17; Macbain; Kennedy (1894) pp. 158–159.

- ↑ McNamee (2012a) ch. genealogical tables tab. 6; Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004); Roberts (1999) p. 181; McDonald (1997) p. 186; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 186; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) p. 25.

- ↑ Oram (2014) p. 3; Penman, MA (2014) p. 62; Daniels (2013) p. 25; Caldwell, D (2008) pp. 49–50; Smith (2007) p. 160; Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004); Oram (2004) p. 123; Macdougall (2001); Sellar (2000) p. 195 n. 37.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) pp. 187–188.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 188; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 259–260, 391 n. 166; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 74–75, 74–75 n. 42; Brown (2004) p. 267 n. 18; Roberts (1999) p. 181; McDonald (1997) p. 187; Barrow (1988) p. 299; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203, 203 n. 12; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 205 n. 9; Thomson, JM (1912) p. 557 § 699; RPS, A1325/2 (n.d.a); RPS, A1325/2 (n.d.b).

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 391 n. 166; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 74–75; Penman, M (2008); Penman, MA (2005) pp. 28, 84.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 259–260.

- ↑ Cameron (2014) pp. 153–154; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 74–75 n. 42; McQueen (2002) p. 287 n. 18; McDonald (1997) p. 187; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 187.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 261.

- ↑ Macdougall (2001).

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 187; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 110; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 102–103.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 187; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 110.

- ↑ Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 110.

- ↑ Kenny (2007) p. 68; McLeod (2005) p. 43; Kingston (2004) p. 47, 47 nn. 89–90; Brown (2004) p. 265 n. 14; Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004); Hamlin (2002) p. 129; Sellar (2000) p. 206; Ó Mainnín (1999) p. 28, 28 n. 95; Maclean-Bristol (1995) p. 168; Bannerman (1986) p. 10; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ Kingston (2004) p. 47, 47 nn. 89–90; Bannerman (1986) p. 10; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203, 203 n. 3; Macphail (1914) p. 20.

- ↑ McLeod (2005) p. 43; Kingston (2004) p. 47, 47 nn. 89–90; Ó Mainnín (1999) p. 28 n. 95; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203, 203 n. 3; Macbain; Kennedy (1894) pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Kingston (2004) p. 47, 47 n. 89.

- ↑ Sellar (1990).

- ↑ Sellar (2000) p. 206.

- ↑ Kingston (2004) p. 47 n. 90; Bannerman (1986) p. 10; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203; Rotuli Scotiæ' (1814) p. 534.

- ↑ Kingston (2004) p. 47 n. 90.

- ↑ Byrne (2008) p. 18.

- ↑ Bannerman (1986) p. 10 n. 46; Macphail (1914) p. 20; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) p. 570; Macbain; Kennedy (1894) pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Coira (2012) p. 246; Ó Mainnín (1999) p. 28 n. 95; Bannerman (1986) pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 257; Bannerman (1986) pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) p. 90.

- ↑ Munro; Munro (1986) p. 282; Sellar (1971) p. 31; Black; Black (n.d.).

- ↑ Caldwell, D (2008) pp. 52–53; Munro, R; Munro, J (2008); Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004); Munro (1986) pp. 60 fig. 5.1, 62; Munro (1981) p. 27; Cokayne; White (1949) p. 146; Bliss (1897) p. 85.

- ↑ Coira (2012) pp. 76 tab. 3.3; Munro (1986) p. 60 fig. 5.1; Macphail (1914) p. 23; MacDonald; MacDonald (1900) p. 190; Macbain; Kennedy (1894) pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Coira (2012) p. 76 tab. 3.3; Roberts (1999) p. 99 fig. 5.2; Macphail (1914) p. 23; MacDonald; MacDonald (1900) p. 190; Macbain; Kennedy (1894) pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Cathcart (2006) p. 14, 14 n. 32; Clark (1900) p. 164.

- ↑ Ross (2014) p. 107; Cathcart (2006) p. 14, 14 n. 33; Macphail (1914) p. 16.

- ↑ Ross (2014) pp. 112–114.

- 1 2 3 Brown (2004) p. 77 tab. 4.1; Sellar (2000) p. 194 tab ii.

- ↑ Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. xviii–xix.

- ↑ Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 39.

- 1 2 Boardman, S (2006) pp. 18, 32 nn. 51–52; Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 32 n. 52; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 42.

References

Primary sources

- "Annala Uladh: Annals of Ulster Otherwise Annala Senait, Annals of Senat". Corpus of Electronic Texts (28 January 2003 ed.). University College Cork. 2003. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Annala Uladh: Annals of Ulster Otherwise Annala Senait, Annals of Senat". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Annála Connacht". Corpus of Electronic Texts (25 January 2011 ed.). University College Cork. 2011a. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Annála Connacht". Corpus of Electronic Texts (25 January 2011 ed.). University College Cork. 2011b. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (23 October 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 February 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Annals of Loch Cé". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Annals of Loch Cé". Corpus of Electronic Texts (5 September 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (3 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013a. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013b. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Bain, Joseph, ed. (1884). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 2, A.D. 1272–1307. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via Internet Archive.

- Bain, Joseph, ed. (1887). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 3, A.D. 1307–1357. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via Internet Archive.

- Bain, Joseph, ed. (1888). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 4, A.D. 1357–1509. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via Internet Archive.

- Black, R; Black, M (n.d.). "Kindred 27 MacLachlan". 1467 Manuscript. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- Bliss, WH, ed. (1897). Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers Relating to Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 3. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office – via Internet Archive.

- Calendar of the Close Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward I. Vol. 5, A.D. 1302–1307. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1908 – via Internet Archive.

- Clark, JT, ed. (1900). Genealogical Collections Concerning Families in Scotland. Publications of the Scottish History Society (series vol. 33). 1. Edinburgh: Scottish History Society – via Internet Archive.

- Duncan, AAM, ed. (2007) [1997]. The Bruce. Canongate Classics. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-0-86241-681-2 – via Google Books.

- Eyre-Todd, G, ed. (1907). The Bruce: Being the Metrical History of Robert Bruce King of the Scots. London: Gowans & Gray – via Internet Archive.

- Laing, D, ed. (1878). Fac Simile of an Ancient Heraldic Manuscript Emblazoned by Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount. Edinburgh: William Paterson – via Internet Archive.

- Liber Sancte Marie de Melrose: Munimenta Vetustiora Monasterii Cisterciensis de Melros. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. 1836 – via Internet Archive.

- List of Diplomatic Documents, Scottish Documents, and Papal Bulls Preserved in the Public Record Office. Lists and Indexes (series vol. 49). New York: Kraus Reprint Corporation. 1963 [1923] – via Internet Archive.

- Macbain, A; Kennedy, J, eds. (1894). Reliquiæ Celticæ: Texts, Papers and Studies in Gaelic Literature and Philology, Left by the Late Rev. Alexander Cameron, LL.D. Vol. 2, Poetry, History, and Philology. Inverness: The Northern Counties Newspaper and Printing and Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- Mackenzie, WM, ed. (1909). The Bruce. London: Adam and Charles Black – via Internet Archive.

- Macphail, JRN, ed. (1914). Highland Papers. Publications of the Scottish History Society, Second Series (series vol. 5). Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Scottish History Society – via Internet Archive.

- Macphail, JRN, ed. (1916). Highland Papers. Publications of the Scottish History Society, Second Series (series vol. 12). Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable – via Internet Archive.

- Murphy, D, ed. (1896). The Annals of Clonmacnoise. Dublin: Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland – via Internet Archive.

- "PoMS, H1/27/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- "PoMS, H3/0/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d.a. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "PoMS, H3/0/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d.b. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "PoMS, H3/0/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d.c. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "PoMS, H3/31/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d.a. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "PoMS, H3/31/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d.b. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "PoMS, H3/31/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d.c. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "PoMS, H3/33/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "PoMS, H3/90/11". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "PoMS, H3/381/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "PoMS, H5/3/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 80039". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 80065". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 80071". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 83146". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84282". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84286". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84292". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 84392". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 86691". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 88525". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 88534". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 88734". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- Riley, HT, ed. (1873). Registra Quorundam Abbatum Monasterii S. Albani, Qui Sæculo XVmo Floruere. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 1. London: Longman & Co – via Internet Archive.

- Robertson, W, ed. (1798). An Index Drawn Up About the Year 1629, of Many Records of Charters, Granted by the Different Sovereigns of Scotland Between the Years 1309 and 1413. Edinburgh: Murray & Cochrane – via Internet Archive.

- "RPS, 1309/1". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.a. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "RPS, 1309/1". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.b. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "RPS, A1325/2". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.a. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "RPS, A1325/2". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.b. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londinensi. Vol. 1. His Majesty King George III. 1814 – via Google Books.

- Rymer, T; Sanderson, R, eds. (1816). Fœdera, Conventiones, Litteræ, Et Cujuscunque Generis Acta Publica, Inter Reges Angliæ, Et Alios Quosvis Imperatores, Reges, Pontifices, Principes, Vel Communitates. Vol. 1 (pt. 2). London – via HathiTrust.

- Simpson, GG; Galbraith, JD, eds. (n.d.). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 5, (Supplementary) A.D. 1108–1516. Scottish Record Office – via Internet Archive.

- "Sir David Lindsay's Armorial". The Heraldry Society of Scotland. n.d. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1871). Johannis de Fordun Chronica Gentis Scotorum. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas – via Internet Archive.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1872). John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas – via Internet Archive.

- "Source Name / Title: AU, 1315 [1318], p. 433". The Galloglass Project. n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Source Name / Title: The Annals of Connacht (AD 1224–1544), ed. A. Martin Freeman (Dublin: The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1944), p. 253". The Galloglass Project. n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1870). Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via Internet Archive.

- Sweetman, HS; Handcock, GF, eds. (1886). Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland, Preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office, London, 1302–1307. London: Longman & Co. – via Internet Archive.

- "The Balliol Roll". The Heraldry Society of Scotland. n.d. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Thomson, JM, ed. (1912). Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum: The Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, A.D. 1306–1424 (New ed.). Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via HathiTrust.

- Walsh, P (1938). "O Donnell Genealogies". Analecta Hibernica. 8: 373, 375–418. ISSN 0791-6167. JSTOR 30007662 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

Secondary sources

- Addyman, T; Oram, R (2012). "Mingary Castle Ardnamurchan, Highland: Analytical and Historical Assessment for Ardnamurchan Estate". Mingarry Castle Preservation and Restoration Trust. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Bannerman, J (1986). The Beatons: A Medical Kindred in the Classical Gaelic Tradition. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers. ISBN 0 85976 139 8 – via Google Books.

- Bannerman, J (1998) [1993]. "MacDuff of Fife". In Grant, A; Stringer, KJ. Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 20–38. ISBN 0 7486 1110 X.

- Barrow, GWS (1973). The Kingdom of the Scots: Government, Church and Society From the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Century. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Barrow, GWS (1988) [1965]. Robert Bruce & the Community of the Realm of Scotland (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 85224 539 4.

- Barrow, GWS (2003) [1973]. The Kingdom of the Scots: Government, Church and Society From the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Century (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 7486 1802 3 – via Google Books.

- Birch, WDG (1905). History of Scottish Seals. Vol. 1, The Royal Seals of Scotland. Stirling: Eneas Mackay – via Internet Archive.

- Barrow, GWS (2008). "Robert I (1274–1329)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3754. Retrieved 20 January 2014. (subscription required (help)).

- Bateman, M; McLeod, W, eds. (2007). Duanaire Na Sracaire, Songbook of the Pillagers: Anthology of Scotland's Gaelic Verse to 1600. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-181-1 – via Google Books.

- "Battle / Event Title: Dundalk". The Galloglass Project. n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Boardman, S (2001). "Kingship: 4. Bruce Dynasty". In Lynch, M. The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford Companions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 362–363. ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Boardman, S (2006). The Campbells, 1250–1513. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-0-85976-631-9 – via Google Books.

- Boardman, S (2007). "The Gaelic World and the Early Stewart Court" (PDF). In Broun, D; MacGregor, M. Mìorun Mòr nan Gall, 'The Great Ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland Perceptions of the Highlands, Medieval and Modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow. pp. 83–109. OCLC 540108870.

- Boardman, SI (2004). "MacRuairi, Ranald, of Garmoran (d. 1346)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54286. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Brown, M (2004). The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland (series vol. 4). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0748612386 – via Google Books.

- Brown, M (2008). Bannockburn: The Scottish War and the British Isles, 1307–1323. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3332-6.

- Brown, M; Boardman, SI (2005). "Survival and Revival: Late Medieval Scotland". In Wormald, J. Scotland: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 69–92. ISBN 0-19-820615-1.

- Byrne, FJ (2008) [1987]. "The Trembling Sod: Ireland in 1169". In Cosgrove, A. Medieval Ireland, 1169–1534. New History of Ireland (series vol. 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199539703.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-953970-3 – via Oxford Scholarship Online.

- Caldwell, D (2008). Islay: The Land of the Lordship. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- Caldwell, DH (2004). "The Scandinavian Heritage of the Lordship of the Isles". In Adams, J; Holman, K. Scandinavia and Europe, 800–1350: Contact, Conflict, and Coexistence. Medieval Texts and Cultures of Northern Europe (series vol. 4). Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. pp. 69–83. doi:10.1484/M.TCNE-EB.3.4100. ISBN 2-503-51085-X.

- Cameron, C (2014). "'Contumaciously Absent'? The Lords of the Isles and the Scottish Crown". In Oram, RD. The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 68). Leiden: Brill. pp. 146–175. doi:10.1163/9789004280359_008. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Campbell of Airds, A (2000). A History of Clan Campbell. Vol. 1, From Origins to Flodden. Edinburgh: Polygon at Edinburgh. ISBN 1-902930-17-7.

- Campbell of Airds, A (2014). "West Highland Heraldry and The Lordship of the Isles". In Oram, RD. The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 68). Leiden: Brill. pp. 200–210. doi:10.1163/9789004280359_010. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Cathcart, A (2006). Kinship and Clientage: Highland Clanship, 1451–1609. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 20). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978 90 04 15045 4. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Cochran-Yu, DK (2015). A Keystone of Contention: The Earldom of Ross, 1215–1517 (PhD thesis). University of Glasgow – via Glasgow Theses Service.

- Coira, MP (2012). By Poetic Authority: The Rhetoric of Panegyric in Gaelic Poetry of Scotland to c. 1700. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-78046-003-1 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Cokayne, GE; White, GH, eds. (1949). The Complete Peerage. Vol. 11. London: The St Catherine Press.

- Collard, J (2007). "Effigies ad Regem Angliae and the Representation of Kingship in Thirteenth-Century English Royal Culture" (PDF). Electronic British Library Journal: 1–26. ISSN 1478-0259.

- Cornell, D (2009). Bannockburn: The Triumph of Robert the Bruce. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14568-7.

- Daniels, PW (2013). The Second Scottish War of Independence, 1332–41: A National War? (MA thesis). University of Glasgow – via Glasgow Theses Service.

- Davies, RR (2000). The First English Empire: Power and Identities in the British Isles, 1093–1343. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820849-9.

- Duffy, S (1991). The 'Continuation' of Nicholas Trevet: A New Source for the Bruce Invasion. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 91C. pp. 303–315. eISSN 2009-0048. ISSN 0035-8991. JSTOR 25516086 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Duffy, S (1998). "The Gaelic Account of the Bruce Invasion Cath Fhochairte Brighite: Medieval Romance or Modern Forgery?". Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society. 13 (1): 59–121. ISSN 0488-0196. JSTOR 29745299 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Duffy, S (2002). "The Bruce Brothers and the Irish Sea World, 1306–29". In Duffy, S. Robert the Bruce's Irish Wars: The Invasions of Ireland 1306–1329. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. pp. 45–70. ISBN 0-7524-1974-9 – via Academia.edu.

- Duffy, S (2005). "Bruce, Edward (c. 1275–1318)". In Duffy, S. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 51–53. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Duffy, S (2007). "The Prehistory of the Galloglass". In Duffy, S. The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0 – via Google Books.

- Dunbar, JG; Duncan, AAM (1971). "Tarbert Castle: A Contribution to the History of Argyll". Scottish Historical Review. 50 (1): 1–17. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25528888 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Duncan, AAM (1992). "The War of the Scots, 1306–23". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 2: 125–151. eISSN 1474-0648. ISSN 0080-4401. JSTOR 3679102 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Duncan, AAM (2010). "Edward Bruce". In Rogers, CJ. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-19-533403-6 – via Google Books.

- Duncan, AAM; Brown, AL (1956–1957). "Argyll and the Isles in the Earlier Middle Ages" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 90: 192–220 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- Fisher, I (2005). "The Heirs of Somerled". In Oram, RD; Stell, GP. Lordship and Architecture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 85–95. ISBN 978 0 85976 628 9 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Frame, R (1998). Ireland and Britain, 1170–1450. London: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 1-85285-149-X.

- Fraser, W, ed. (1888). The Red Book of Menteith. Vol. 2. Edinburgh – via Internet Archive.

- Gledhill, J (2015). "The Scots and the Battle of Bannockburn (1314)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (September 2015 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/106200. Retrieved 18 April 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Grant, A (2006) [2000]. "Fourteenth-Century Scotland". In Jones, M. The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 6, c.1300–c.1415. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 345–375. ISBN 0-521-36290-3.

- Hamlin, A (2002). "Dungiven Priory and the Ó Catháin Family". In Ní Chatháin, P; Richter, M; Picard, Jean-Michel. Ogma: Essays in Celtic Studies in Honour of Próinséas Ní Chatháin. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 118–137. ISBN 1-85182-671-8 – via Google Books.

- Hickey, R (2011). The Dialects of Irish: Study of a Changing Landscape. Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs (series vol. 230). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. ISBN 978-3-11-023804-4. ISSN 1861-4302 – via Google Books.

- "Individual(s) / Person(s): Mac Ruaidhri, King of the Hebrides - Ri Innsi Gall". The Galloglass Project. n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Kenny, G (2007). Anglo-Irish and Gaelic Women in Ireland, c.1170–1540. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-984-2 – via Google Books.

- King, A (2015). "The English and the Battle of Bannockburn (act. 1314)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (September 2015 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/106194. Retrieved 18 April 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Kingston, S (2004). Ulster and the Isles in the Fifteenth Century: The Lordship of the Clann Domhnaill of Antrim. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 1-85182-729-3 – via Google Books.

- Laing, H (1850). Descriptive Catalogue of Impressions From Ancient Scottish Seals, Royal, Baronial, Ecclesiastical, and Municipal, Embracing a Period From A.D. 1094 to the Commonwealth. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club – via Internet Archive.

- Laing, H (1866). Supplemental Descriptive Catalogue of Ancient Scottish Seals, Royal, Baronial, Ecclesiastical, and Municipal, Embracing the Period From A.D. 1150 to the Eighteenth Century. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas – via Internet Archive.

- Lamont, WD (1981). "Alexander of Islay, Son of Angus Mór". Scottish Historical Review. 60 (2): 160–169. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25529420 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Lydon, J (1992). "The Scottish Soldier in Medieval Ireland: The Bruce Invasion and the Galloglass". In Simpson, GG. The Scottish Soldier Abroad, 1247–1967. The Mackie Monographs (series vol. 2). Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers. ISBN 0 85976 341 2 – via Google Books.

- MacDonald, A; MacDonald, A (1896). The Clan Donald. Vol. 1. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- MacDonald, A; MacDonald, A (1900). The Clan Donald. Vol. 2. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- MacDonald, IG (2013). Clerics and Clansmen: The Diocese of Argyll between the Twelfth and Sixteenth Centuries. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 61). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18547-0. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Macdonald, WR (1904). Scottish Armorial Seals. Edinburgh: William Green and Sons – via Internet Archive.

- Macdougall, N (2001). "Isles, Lordship of the". In Lynch, M. The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford companions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 347–348. ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Maclean-Bristol, N (1995). Warriors and Priests: The History of the Clan Maclean, 1300–1570. East Linton: Tuckwell Press – via Google Books.

- McAndrew, BA (1992). "Some Ancient Scottish Arms". The Heraldry Society. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- McAndrew, BA (1999). "The Sigillography of the Ragman Roll" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 129: 663–752 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- McAndrew, BA (2006). Scotland's Historic Heraldry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843832614 – via Google Books.

- McDonald, RA (1995). "Images of Hebridean Lordship in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries: The Seal of Raonall Mac Sorley". Scottish Historical Review. 74 (2): 129–143. doi:10.3366/shr.1995.74.2.129. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25530679 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs (series vol. 4). East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McDonald, RA (2004). "Coming in From the Margins: The Descendants of Somerled and Cultural Accommodation in the Hebrides, 1164–1317". In Smith, B. Britain and Ireland, 900–1300: Insular Responses to Medieval European Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–198. ISBN 0-511-03855-0.

- McDonald, RA (2006). "The Western Gàidhealtachd in the Middle Ages". In Harris, B; MacDonald, AR. Scotland: The Making and Unmaking of the Nation, c.1100–1707. Vol. 1. Dundee: Dundee University Press. ISBN 978-1-84586-004-2 – via Google Books.

- McLeod, W (2002). "Rí Innsi Gall, Rí Fionnghall, Ceannas nan Gàidheal: Sovereignty and Rhetoric in the Late Medieval Hebrides". Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies. 43: 25–48. ISSN 1353-0089 – via Google Books.

- McLeod, W (2005) [2004]. "Political and Cultural Background". Divided Gaels: Gaelic Cultural Identities in Scotland and Ireland 1200–1650. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199247226.003.0002. ISBN 0-19-924722-6 – via Oxford Scholarship Online.

- McNamee, C (2012a) [2006]. Robert Bruce: Our Most Valiant Prince, King and Lord. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-0-85790-496-6.

- McNamee, C (2012b) [1997]. The Wars of the Bruces: Scotland, England and Ireland, 1306–1328. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-0-85790-495-9.

- McQueen, AAB (2002). The Origins and Development of the Scottish Parliament, 1249–1329. University of St Andrews – via Research@StAndrews:FullText.

- Munro, J (1981). "The Lordship of the Isles". In Maclean, L. The Middle Ages in the Highlands. Inverness: Inverness Field Club.

- Munro, J (1986). "The Earldom of Ross and the Lordship of the Isles" (PDF). In John, J. Firthlands of Ross and Sutherland. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 59–67. ISBN 0 9505994 4 1 – via Scottish Society for Northern Studies.

- Munro, J; Munro, RW (1986). The Acts of the Lords of the Isles, 1336–1493. Scottish History Society. ISBN 0 906245 07 9 – via Google Books.

- Munro, R; Munro, J (2008). "Ross Family (per. c.1215–c.1415)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54308. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004). "MacDonald family (per. c.1300–c.1500)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54280. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Nicholls, K (2007). "Scottish Mercenary Kindreds in Ireland, 1250–1600". In Duffy, S. The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 86–105. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0 – via Google Books.

- Oram, RD (2004). "The Lordship of the Isles, 1336–1545". In Omand, D. The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 123–139. ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Oram, RD (2014). "Introduction: A Celtic Dirk at Scotland's Back? The Lordship of the Isles Mainstream Scottish Historiography since 1828". In Oram, RD. The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 68). Leiden: Brill. pp. 1–39. doi:10.1163/9789004279469_002. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Ó Mainnín, MB (1999). 'The Same in Origin and in Blood': Bardic Windows on the Relationship between Irish and Scottish Gaels in the Period c. 1200–1650. Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies. 38. pp. 1–52. ISSN 1353-0089 – via Google Books.

- Penman, M (2008). "Robert I (1306–1329)". In Brown, M; Roland, T. Scottish Kingship, 1306–1542. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 20–40. ISBN 9781904607823 – via Stirling Online Research Repository.

- Penman, M (2014). Robert the Bruce: King of the Scots. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14872-5 – via Google Books.

- Penman, MA (2005) [2004]. David II, 1329–71. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-0-85976-603-6 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Penman, MA (2014). "The MacDonald Lordship and the Bruce Dynasty, c.1306–c.1371". In Oram, RD. The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 68). Leiden: Brill. pp. 62–87. doi:10.1163/9789004279469_004. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Prestwich, M (1988). Edward I. English Monarchs. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06266-3 – via Google Books.

- Reid, WS (1960). "Sea-Power in the Anglo-Scottish War, 1296–1328". The Mariner's Mirror. 46 (1): 7–23. doi:10.1080/00253359.1960.10658467. ISSN 0025-3359.

- Rixson, D (1982). The West Highland Galley. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-874744-86-6.

- Roberts, JL (1999). Lost Kingdoms: Celtic Scotland and the Middle Ages. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 7486 0910 5.

- Ross, A (2014). "Ghille Chattan Mhor and Clann Mhic an Tòisich Lands in the Clann Dhomhnail Lordship of Lochaber". In Oram, RD. The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 68). Leiden: Brill. pp. 101–122. doi:10.1163/9789004280359_006. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Sellar, WDH (1971). "Family Origins in Cowal and Knapdale". Scottish Studies: The Journal of the School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh. 15: 21–37. ISSN 0036-9411 – via Google Books.

- Sellar, WDH (1990). "Review of K Simms, From Kings to Warlords: The Changing Political Structure of Gaelic Ireland in the Later Middle Ages". Irish Historical Studies. 27 (106): 165–167. eISSN 2056-4139. ISSN 0021-1214. JSTOR 30006517 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Sellar, WDH (2000). "Hebridean Sea Kings: The Successors of Somerled, 1164–1316". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA. Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 187–218. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Sellar, WDH (2004a). "MacDougall, Alexander, Lord of Argyll (d. 1310)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49385. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Sellar, WDH (2004b). "MacDougall, John, Lord of Argyll (d. 1316)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54284. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Sellar, WDH (2016). "Review of RD Oram, The Lordship of the Isles". Northern Scotland. 7 (1): 103–107. doi:10.3366/nor.2016.0114. eISSN 2042-2717. ISSN 0306-5278.