1st Army Group (Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

| 1st Army Group | |

|---|---|

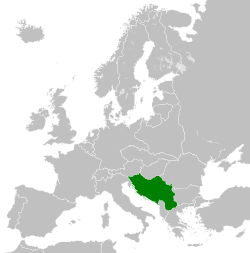

| Country |

|

| Branch | Royal Yugoslav Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Field army[lower-alpha 1] |

| Engagements | Invasion of Yugoslavia (1941) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Milorad Petrović |

The 1st Army Group was a Royal Yugoslav Army formation raised prior to the German-led Axis invasion of the Yugoslavia in April 1941 during World War II. It consisted of the 4th Army, 7th Army, and the 1st Cavalry Division, which was the army group reserve. It was responsible for the defence of northwestern Yugoslavia, with the 4th Army defending the western sector along the Yugoslav-Hungarian border, and the 7th Army defending the eastern sector along the borders with Germany and Italy.

Despite concerns over a possible Axis invasion, orders for the general mobilisation of the Royal Yugoslav Army were not issued by the government until 3 April 1941, out of fear this would offend Adolf Hitler and precipitate war. When the invasion commenced on 6 April, the component formations of 1st Army Group were only partially mobilised, and on the first day the Germans seized bridges over the Drava river in both sectors and several mountain passes in the 7th Army sector. In the 4th Army sector, the formation and expansion of German bridgeheads across the Drava were facilitated by fifth column elements of the Ustaše and sympathetic units of the paramilitary Civic and Peasant Guards of the Croatian Peasant Party. Revolts of Croat soldiers broke out in all three divisions of the 4th Army in the first few days, causing significant disruption to mobilisation and deployment. The 1st Army Group was also weakened by fifth column activities within its major units, and the chief-of-staff and chief of operations of the headquarters of 1st Army Group aided both Croat Ustaše and Slovene separatists in the 4th and 7th Army sectors respectively. The revolts within the 4th Army were of great concern to the commander of the 7th Army, but Petrović did not permit him to withdraw from border areas until the night of 7/8 April, which was followed by the German capture of Maribor as they continued to expand their bridgeheads.

The 4th Army also began to withdraw southwards on 9 April, and on 10 April it quickly ceased to exist as an operational formation in the face of two determined armoured thrusts by the XLVI Motorised Corps, one of which captured Zagreb that evening. Italian offensive operations also began, with thrusts towards Ljubljana and down the Adriatic coast, capturing over 30,000 Yugoslav troops near Delnice. When fifth column elements arrested the staffs of 1st Army Group, 4th Army and 7th Army on 11 April, the 1st Army Group effectively ceased to exist. On 12 April, a German armoured column linked up with the Italians near the Adriatic coast, encircling the remnants of the withdrawing 7th Army. Remnants of the 4th Army attempted to establish defensive positions in northeastern Bosnia, but were quickly brushed aside by German armour as it drove towards Sarajevo. The Yugoslav High Command unconditionally surrendered on 18 April.

Background

The Royal Yugoslav Army (Serbo-Croatian: Vojska Kraljevine Jugoslavije, VKJ) was formed after World War I as the army of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Kingdom of SCS), when that country was created on 1 December 1918. To defend the new kingdom, an army was formed around the nucleus of the victorious Royal Serbian Army combined with armed formations raised in the former parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that joined with the Kingdom of Serbia to form the new state. Many former Austro-Hungarian officers and soldiers became members of the new army.[1] From its beginning, the army, like other aspects of public life in the new kingdom, was dominated by ethnic Serbs, who saw the army as a means by which to secure Serb hegemony in the new kingdom.[2]

The development of the army was hampered by the poor economy of the kingdom, and this continued through the 1920s. In 1929, King Alexander changed the name of the country to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, at which time the army became the VKJ. The army budget remained tight, and as tensions rose across Europe during the 1930s, it became hard to secure weapons and munitions from other countries.[3] Consequently, at the time World War II broke out in September 1939, the VKJ had several serious weaknesses, which included reliance on draught animals for transport, and the large size of its formations. For example, infantry divisions had a wartime strength of 26,000–27,000 men,[4] as compared to contemporary British infantry divisions of half that strength.[5] These characteristics resulted in slow, unwieldy formations, and the inadequate supply of arms and munitions meant that even the very large Yugoslav formations had low firepower.[6] Older generals better suited to the trench warfare of World War I were combined with an army that was not equipped or trained to resist the fast-moving combined arms approach used by the Germans in Poland and France.[7][8]

The weaknesses of the VKJ in strategy, structure, equipment, mobility and supply were exacerbated to a significant degree by the lack of unity across Yugoslavia which had resulted from two decades of Serb hegemony,[9] and the attendant lack of political legitimacy achieved by the central government.[10] Attempts to address the lack of unity came too late to ensure that the VKJ was a cohesive force. Fifth column activity was also a serious concern, not only from the Croatian nationalist Ustaše, but from the Slovene and ethnic German minorities in the country.[9]

Formation and composition

Yugoslav war plans saw the 1st Army Group being raised as a formation at the time of mobilisation. It was to be commanded by Armijski đeneral[lower-alpha 2] Milorad Petrović, and was to consist of the 4th Army, commanded by Armijski đeneral Petar Nedeljković, the 7th Army, commanded by Diviziski General[lower-alpha 3] Dušan Trifunović, and the 1st Cavalry Division.[12] The 4th Army was organised and mobilised on a geographic basis from the peacetime 4th Army District.[13] On mobilisation it would consist of three divisions, a brigade-strength infantry detachment, one horsed cavalry regiment and one infantry regiment, and was supported by artillery, anti-aircraft artillery, border guards, and air reconnaissance elements of the Royal Yugoslav Air Force.[14] The troops of the 4th Army included a high percentage of Croats.[15] The 7th Army did not have a corresponding peacetime army district, and, like the 1st Army Group, was to be formed at the time of mobilisation.[16] It would consist of two divisions, one divisional-strength mountain detachment, one brigade-strength mountain detachment and a brigade-strength infantry detachment, with artillery and anti-aircraft artillery support, and also had air reconnaissance assets available.[17] The 1st Cavalry Division was a horsed cavalry formation that existed as part of the peacetime army, although significant parts of the peacetime division were earmarked to join other formations when they were mobilised.[18] The 1st Army Group did not control any additional support units.[12]

Deployment plan and mobilisation

The deployment plan for 1st Army Group saw the 4th Army deployed in a cordon behind the Drava between Varaždin and Slatina,[19] with formations centred around the towns of Ivanec, Varaždin, Koprivnica and Virovitica.[20][21] The 7th Army deployment plan saw its formations placed in a cordon along the border region from the Adriatic coast near Senj north into the Julian Alps and along the Reich border to Maribor.[20] Of the formations of the 1st Army Group, the mountain detachments and infantry detachment of the 7th Army were largely mobilised, one infantry division of the 4th Army was partly mobilised, and the remaining four infantry divisions and the 1st Cavalry Division had only commenced mobilisation.[22] To the right of the 4th Army was the 2nd Army of the 2nd Army Group,[19] with the army group boundary running from just east of Slatina through Požega towards Banja Luka. On the left flank of the 1st Army Group, the Adriatic coast was defended by Coastal Defence Command.[20]

After unrelenting pressure from Adolf Hitler, Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941. On 27 March, a military coup d'état overthrew the government that had signed the pact, and a new government was formed under the VVKJ commander, Armijski đeneral Dušan Simović.[23] A general mobilisation was not called by the new government until 3 April 1941, out of fear of offending Hitler and thus precipitating war.[24] The Yugoslav historian Velimir Terzić describes the mobilisation of all formations of the 1st Army Group on 6 April as "only partial".[25]

Operations

6–9 April

4th Army sector

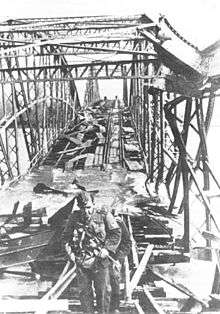

German Army headquarters wanted to capture the bridges over the Drava intact, and from 1 April had issued orders to the German 2nd Army to conduct preliminary operations aimed at seizing the bridge at Barcs and the railway bridge northeast of Koprivnica by coup de main. As a result, limited objective attacks were launched along the line of the Drava by the XLVI Motorised Corps, despite the fact that they were not expected to launch offensive operations until 10 April.[26] Similar operations occurred on the extreme left flank of the 4th Army, where raiding parties and patrols from LI Infantry Corps seized the high ground on the south side of the Drava.[27]

In the early hours of 6 April 1941, units of the 4th Army were located at their mobilisation centres or were marching toward the Hungarian border.[28] LI Infantry Corps seized the intact bridge over the Drava at Gornja Radgona,[27] and Yugoslav border troops in the Prekmurje region were attacked by German troops advancing across the Reich border, and began withdrawing south into the Međimurje region. Germans troops also crossed the Hungarian border and attacked border troops at Dolnja Lendava. Shortly after this, further attacks were made along the Drava between Ždala and Gotalovo in the area of the 27th Infantry Division Savska with the intention of securing crossings over the river, but they were unsuccessful. The Germans cleared most of Prekmurje up to Murska Sobota and Ljutomer during the day,[29] and a bicycle-mounted detachment of the 183rd Infantry Division captured Murska Sobota without encountering resistance.[27] During the day, the German Luftwaffe bombed and strafed Yugoslav positions and troops on the march. By the afternoon, German troops had captured Dolnja Lendava,[29] and by the evening it had become clear to the Germans that the Yugoslavs would not be resisting stubbornly at the border. XLVI Motorised Corps was then ordered to begin seizing bridges over the Drava at Mursko Središće, Letenye, Zákány and Barcs. These local attacks were sufficient to inflame dissent within the largely Croat 4th Army, who refused to resist Germans they considered their liberators from Serbian oppression during the interwar period.[30]

In the afternoon of 6 April, German aircraft caught the air reconnaissance assets of the 4th Army on the ground at Velika Gorica, destroying most of them.[31] The continuing mobilisation and concentration of the 4th Army was hampered by escalating fifth column activities and propaganda fomented by the Ustaše. Some units stopped mobilising, or began returning to their mobilisation centres from their concentration areas. During the day, Yugoslav sabotage units attempted to destroy bridges over the Mura at Letenye, Mursko Središće and Kotoriba, and over the Drava at Gyékényes. These attempts were only partially successful, due to the influence of Ustaše propaganda and the countermanding of the demolition orders by the chief of staff of the 27th Infantry Division Savska.[29] The Yugoslav radio network in the 4th Army area was sabotaged by the Ustaše on 6 April, and radio communications within the 4th Army remained poor throughout the fighting.[32]

Early on 7 April, reconnaissance units of the XLVI Motorised Corps crossed the Mura at Letenye and Mursko Središće and captured Čakovec.[33] In the face of this German advance, Yugoslav border troops withdrew towards the Drava.[34] Other elements of XLVI Motorised Corps crossed the Drava at Gyékényes and attacked towards Koprivnica. Elements of the 27th Infantry Division Savska took up defensive positions to stop this German penetration and Petrović ordered Nedeljković to mount a counter-attack against the bridgehead. By nightfall the counter-attack had not materialised, the defenders had withdrawn to Koprivnica, and Nedeljković had resolved to counter-attack on the following morning.[28][35] Also on 7 April, the few remaining reconnaissance aircraft of the 4th Army mounted attacks on a bridge over the Drava at Gyékényes.[36] The bridge at Gyékényes was destroyed later that day by sabotage units.[33]

In the early evening, German units in regimental strength began to cross the Drava near Barcs and established a second bridgehead in the sector of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska. Affected by Ustaše propaganda, the border troops abandoned their positions and withdrew to Virovitica.[34] Fifth column activities within units of the 4th Army were fomented by the Croatian fascist organisation, the Ustaše, which facilitated German establishment of the bridgehead at Barcs, and resulted in a number of significant revolts within units. Of two regiments of the 42nd Infantry Division Murska, all but two battalions revolted and refused to deploy into their allocated positions. Similarly, the 108th Infantry Regiment of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska, which had mobilised in Bjelovar, was marching towards Virovitica to take up positions. On the night of 7/8 April, the Croats of the 108th Regiment revolted, arrested their Serb officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers. The regiment then marched back to Bjelovar, where it joined up with other rebellious units about noon on 8 April.[28] The revolt of the 108th Regiment meant that the entire frontage of the division had to be covered by a single regiment.[37] During the night, patrols were sent towards the German bridgehead, but Ustaše sympathisers misled them into believing the Germans were already across the Drava at Barcs in strength.[34] The Germans were subsequently able to consolidate their bridgehead at Barcs overnight.[28] By late evening on 7 April, Petrović's reports to Supreme Headquarters noted that the 4th Army was exhausted and its morale had been degraded significantly, and that Nedeljković concurred with his commander's assessment.[34]

On 8 April, Josip Broz Tito and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, then located in Zagreb, along with the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia, sent a delegation to the headquarters of the 4th Army urging them to issue arms to workers to help defend Zagreb. Pavle Gregorić, who was a member of both Central Committees, went to 4th Army headquarters twice, and was able to speak briefly with Nedeljković, but could not convince him to do so. On that same day, the leader of the Croatian Peasant Party, Vladko Maček who had returned to Zagreb after briefly joining Simović's post-coup d'état government, agreed to send an emissary to the 108th Infantry Regiment of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska urging them to obey their officers, but they did not respond to his appeal.[38]

When the Germans began to expand their bridgehead at Barcs, the rebel Croat troops at Bjelovar made contact with them,[28] and the 4th Army began to withdraw southwards on 9 April.[39] On the night of 9/10 April, those Croats that had remained with their units began to desert or turn on their commanders. The 27th Infantry Division Savska suffered from similar revolts, which eased the German capture of Koprivnica.[40]

7th Army sector

The border between the Reich and Yugoslavia was unsuitable for motorised operations.[41] Due to the short notice of the invasion, the elements of the invading 2nd Army that would make up LI Infantry Corps and XLIX Mountain Corps had to be assembled from France, Germany and the Slovak Republic, and nearly all encountered difficulties in reaching their assembly areas.[42] In the interim, the Germans formed a special force under the code name Feuerzauber (Magic Fire). This force was initially intended to merely reinforce the 538th Frontier Guard Division, who were manning the border. On the evening of 5 April, one of the aggressive Feuerzauber detachment commanders, Hauptmann Palten led his Kampfgruppe Palten across the Mura from Spielfeld and, having secured the bridge, began attacking bunkers and other Yugoslav positions on the high ground, and sent patrols deep into the Yugoslav border fortification system. Due to a lack of Yugoslav counter-attacks, many of these positions remained in German hands into 6 April.[41]

LI Infantry Corps were tasked with attacking towards Maribor then driving towards Zagreb, while the XLIX Mountain Corps was to capture Dravograd then force a crossing on the Sava.[43] On the first day of the invasion, LI Infantry Corps captured the Drava bridges at Mureck and Radkersburg (opposite Radgon) undamaged, and the 183rd Infantry Division captured 300 prisoners. A bicycle-mounted detachment of the 183rd Infantry Division reached the extreme left flank of the Yugoslav 4th Army at Murska Sobota without striking any resistance. The 132nd Infantry Division also pushed south along the Sejanski valley towards Savci.[27]

Late that day, mountain pioneers destroyed some isolated Yugoslav bunkers in the area penetrated by Kampfgruppe Palten.[41] On that day, the governor of the Drava Banovina, Marko Natlačen met with representatives of the major Slovene political parties, and created the National Council of Slovenia, whose aim was to establish a Slovenia independent of Yugoslavia. When he heard the news of fifth column-led revolts within the 4th Army, Trifunović was alarmed, and proposed withdrawal from the border areas, but this was rejected by Petrović. The front along the border with Italy was relatively quiet, with only patrol clashes occurring. The Yugoslav High Command ordered that the 7th Army capture Fiume, across the Rječina river from Sušak, but the order was soon rescinded.[44]

Over the next three days, LI Corps held the lead elements of its two divisions back while the rest of each division detrained in Graz and made their way to the border.[27] All elements of both divisions had unloaded by 9 April.[45] On the afternoon of 7 April, German Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers of Sturzkampfgeschwader 77 escorted by Messerschmitt Bf 109E fighters also caught the Breguet 19s of the 6th Air Reconnaissance Group on the ground at Cerklje, destroying most of them.[31] As a result of the revolts in the 4th Army, on the night of 7/8 April, Petrović ordered the 7th Army to begin to withdraw, first to a line through the Dravinja river, Zidani Most bridge and the right bank of the Krka river. This was subsequently moved back to the line of the Kupa river.[44] On 8 April, disregarding orders from above, Palten led his Kampfgruppe south towards Maribor, and crossed the Pesnica river in pneumatic boats, leaving his unit vehicles behind. In the evening, Palten and his force entered Maribor unopposed, taking 100 prisoners. Kampfgruppe Palten was ordered to return to Spielfeld, and spent the rest of the invasion guarding the border. In the meantime, the forward elements of the two divisions consolidated their bridgeheads, with the 132nd Infantry Division securing Maribor, and the 183rd Infantry Division pushing past Murska Sobota.[27]

The activities of Natlačen and his council continued from the day the invasion commenced, and the Yugoslav High Command soon ordered their arrest. However, the chief of staff of the headquarters of the 1st Army Group, Armiski General Leon Rupnik and the head of the operations staff, Pukovnik[lower-alpha 4] Franjo Nikolić did not carry out the orders.[44] On 9 April, the 6th Air Reconnaissance Group airfield at Cerklje was again attacked by German aircraft.[46]

10–11 April

4th Army sector

Early on 10 April, Nikolić left his post and visited the senior Ustaše leader Slavko Kvaternik in Zagreb. He then returned to the headquarters and redirected 4th Army units around Zagreb to either cease operations or to deploy to innocuous positions. These actions reduced or eliminated armed resistance to the German advance.[47]

On the same day, the Germans broke out of the bridgeheads they had established, with the 14th Panzer Division, supported by dive bombers, crossing the Drava and driving southwest towards Zagreb on snow-covered roads in extremely cold conditions. Initial air reconnaissance indicated large concentrations of Yugoslav troops on the divisional axis of advance, but these troops proved to be withdrawing towards Zagreb.[48] Ustaše and their sympathisers in the paramilitary Civic and Peasant Guards of the Croatian Peasant Party disarmed and captured the staff of several 4th Army units, including the 1st Army Group, and 4th and 7th Armies at Petrinja, and the 4th Army effectively ceased to exist as a formation.[49] Soon after the 14th Panzer Division commenced its attack, the main thrust of the XLVI Motorised Corps, consisting of the 8th Panzer Division leading the 16th Motorised Infantry Division crossed the Drava at Barcs. The 8th Panzer Division turned southeast between the Drava and Sava rivers, and meeting almost no resistance, had reached Slatina by evening.[15]

About 17:45 on 10 April, Kvaternik and SS-Standartenführer (Colonel) Edmund Veesenmayer went to the radio station in Zagreb and Kvaternik proclaimed the creation of the Independent State of Croatia.[50] By 19:30 on 10 April, despite initial resistance, lead elements of the 14th Panzer Division had reached the outskirts of Zagreb, having covered nearly 160 kilometres (99 miles) in a single day.[48] By the time it entered Zagreb, the 14th Panzer Division was met by cheering crowds, and had captured 15,000 Yugoslav troops, and 22 generals, including both Petrović and Trifunović. Held up by freezing weather and snow storms, on 10 April, on the following day LI Corps was approaching Zagreb from the north, and bicycle-mounted troops of the 183rd Infantry Division had turned east to capture Varaždin, along with an entire Yugoslav brigade including its commanding general. On the same day, the German-installed interim Croatian government called on all Croats to stop fighting, and in the evening, LI Infantry Corps entered Zagreb and relieved the 14th Panzer Division.[51] In the face of the assault by the 14th Panzer Division, the 4th Army quickly ceased to exist as an operational formation. The disintegration of the 4th Army was caused largely by fifth column activity, as it was involved in little fighting.[43]

7th Army sector

During the night of 9/10 April, lead elements of the XLIX Mountain Corps, consisting of the 1st Mountain Division de-trained and crossed the border near Bleiburg and advanced southeast towards Celje, reaching a point about 19 kilometres (12 mi) from the town by evening.[48] Luftwaffe reconnaissance sorties revealed that the main body of the 7th Army was withdrawing towards Zagreb, leaving behind light forces to maintain contact with the German bridgeheads. When it received this information, 2nd Army headquarters ordered LI Corps to form motorised columns to pursue the 7th Army south, but extreme weather conditions and flooding of the Drava at Maribor on 10 April slowed the German pursuit.[27]

About 06:00 on 11 April, LI Corps recommenced its push south towards Zagreb, with lead elements exiting the mountains northwest of the city in the evening of the same day,[48] while the 1st Mountain Division captured Celje after some hard marching and difficult fighting. Emissaries from the newly formed National Council of Slovenia approached the commander of XLIX Mountain Corps, General der Infanterie Ludwig Kübler to ask for a ceasefire.[48] Also on 11 April, the Italian 2nd Army commenced offensive operations around 12:00,[51] with the XI Corps pushing through Logatec towards Ljubljana, VI Corps advancing in the direction of Prezid, while strong formations attacked south through Fiume towards Kraljevica and towards Lokve. By this stage, the 7th Army was withdrawing, although some units took advantage of existing fortifications to resist.[49] To assist the Italian advance, the Luftwaffe attacked Yugoslav troops in the Ljubljana region, and the 14th Panzer Division, which had captured Zagreb on 10 April, drove west to encircle the withdrawing 7th Army. The Italians faced little resistance, and captured about 30,000 Yugoslav troops waiting to surrender near Delnice.[51]

Fate

On 10 April, as the situation had become increasingly desperate throughout the country, Dušan Simović, who was both the Prime Minister and Yugoslav Chief of the General Staff, had broadcast the following message:[15]

All troops must engage the enemy wherever encountered and with every means at their disposal. Don't wait for direct orders from above, but act on your own and be guided by your judgement, initiative, and conscience.

On 12 April, the 14th Panzer Division linked up with the Italians at Vrbovsko, closing the ring around the remnants of the 7th Army, before thrusting southeast towards Sarajevo.[52] The remaining elements of the 4th Army had organised defences around the towns of Kostajnica, Bosanski Novi, Bihać and Prijedor, but the 14th Panzer Division quickly broke through at Bosanski Novi and captured Banja Luka,[49] and by 14 April it had captured Jajce.[53] In the wake of the panzers, the 183rd Infantry Division pushed through Zagreb and Sisak to capture Kostajnica and Bosanska Gradiška.[20] On 15 April, the 14th Panzer Division was closing on Sarajevo.[53] The Ustaše arrested the staffs of the 1st Army Group, and 4th and 7th Armies at Petrinja, and the 1st Army Group effectively ceased to exist as a formation.[49] After a delay in locating appropriate signatories for the surrender document, the Yugoslav High Command unconditionally surrendered in Belgrade effective at 12:00 on 18 April.[53]

Notes

- ↑ The Royal Yugoslav Army did not field corps, but their army groups consisted of several armies, which were corps-sized.

- ↑ Armijski đeneral was equivalent to a United States lieutenant general.[11]

- ↑ Diviziski General was equivalent to a United States major general.[11]

- ↑ Pukovnik was equivalent to a United States colonel.[11]

Footnotes

- ↑ Figa 2004, p. 235.

- ↑ Hoptner 1963, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 60.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 58.

- ↑ Brayley & Chappell 2001, p. 17.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Hoptner 1963, p. 161.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 57.

- 1 2 Tomasevich 1975, p. 63.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Niehorster 2013a.

- 1 2 Niehorster 2013b.

- ↑ Krzak 2006, p. 567.

- ↑ Niehorster 2013c.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army 1986, p. 53.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 104.

- ↑ Niehorster 2013d.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 101–102 & 107.

- 1 2 U.S. Army 1986, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 Geografski institut JNA 1952, p. 1.

- ↑ Krzak 2006, p. 582.

- ↑ Barefield 1993, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 34–43.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 64.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 256–260.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 U.S. Army 1986, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Krzak 2006, p. 583.

- 1 2 3 Terzić 1982, p. 293.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, pp. 52–53.

- 1 2 Shores, Cull & Malizia 1987, p. 201.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 265.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 308.

- 1 2 3 4 Terzić 1982, p. 312.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 308–310.

- ↑ Shores, Cull & Malizia 1987, p. 213.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 257.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 50–52.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 68.

- ↑ Krzak 2006, pp. 583–584.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army 1986, p. 55.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, pp. 47–48.

- 1 2 Krzak 2006, p. 584.

- 1 2 3 Krzak 2006, p. 585.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, p. 48.

- ↑ Shores, Cull & Malizia 1987, p. 216.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 U.S. Army 1986, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 Krzak 2006, p. 595.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 52–53.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army 1986, p. 60.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, pp. 60–61.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army 1986, pp. 63–64.

References

Books

- Brayley, Martin; Chappell, Mike (2001). British Army 1939–45 (1): North-West Europe. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-052-0.

- Figa, Jozef (2004). "Framing the Conflict: Slovenia in Search of Her Army". Civil-Military Relations, Nation Building, and National Identity: Comparative Perspectives. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-04645-2 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Geografski institut JNA (1952). "Napad na Jugoslaviju 6 Aprila 1941 godine" [The Attack on Yugoslavia of 6 April 1941]. Istorijski atlas oslobodilačkog rata naroda Jugoslavije [Historical Atlas of the Yugoslav Peoples Liberation War]. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Vojnoistorijski institut JNA [Military History Institute of the JNA].

- Hoptner, J.B. (1963). Yugoslavia in Crisis, 1934–1941. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. OCLC 404664 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Shores, Christopher F.; Cull, Brian; Malizia, Nicola (1987). Air War for Yugoslavia, Greece, and Crete, 1940–41. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-07-6.

- Terzić, Velimir (1982). Slom Kraljevine Jugoslavije 1941 : uzroci i posledice poraza [The Collapse of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1941: Causes and Consequences of Defeat] (in Serbo-Croatian). 2. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Narodna knjiga. OCLC 10276738.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

- U.S. Army (1986) [1953]. The German Campaigns in the Balkans (Spring 1941). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 16940402. CMH Pub 104-4.

Journals and papers

- Barefield, Michael R. (May 1993). "Overwhelming Force, Indecisive Victory: The German Invasion of Yugoslavia, 1941". Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 32251055.

- Krzak, Andrzej (2006). "Operation "Marita": The Attack Against Yugoslavia in 1941". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 19 (3): 543–600. doi:10.1080/13518040600868123. ISSN 1351-8046.

Web

- Niehorster, Dr. Leo (2013a). "Royal Yugoslav Armed Forces Ranks". Dr. Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Niehorster, Dr. Leo (2013b). "Balkan Operations Order of Battle Royal Yugoslavian Army 6th April 1941". Dr. Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- Niehorster, Dr. Leo (2013c). "Balkan Operations Order of Battle Royal Yugoslavian Army 4th Army 6th April 1941". Dr. Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Niehorster, Dr. Leo (2013d). "Balkan Operations Order of Battle Royal Yugoslavian Army 7th Army 6th April 1941". Dr. Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

_location_map.svg.png)