Wright's Coal Tar Soap

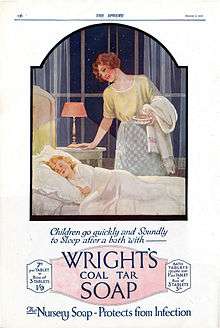

Created by William Valentine Wright in 1860, Wright's Traditional Soap, or Wright's Coal Tar Soap, is a popular brand of antiseptic soap that is designed to thoroughly cleanse the skin. It is an orange colour.

For over 130 years, Wright’s Coal Tar Soap was a popular brand of household soap; it can still be bought in supermarkets and from chemists worldwide. It was developed by William Valentine Wright in 1866 from "liquor carbonis detergens", the liquid by-product of the distillation of coal to make coke; the liquid was made into an antiseptic soap for the treatment of skin diseases.

History

Wright, Sellers & Layman

William Valentine Wright, born in 1826 in Aldeburgh, Suffolk, was a wholesale druggist and chemist who had a small business, W.V. Wright & Co. at 11 Old Fish Street Hill, Doctors' Commons, London. Now non-existent, Old Fish Street Hill south east of St Paul's Cathedral was the 14th century fish market, before Billingsgate (it is not the present-day Fish Street Hill by the Monument). Wright's business can be traced back to that of James Curtis & Co., a wholesale druggist at these premises since 1795.

Wright developed a reputation with his recipe for non-alcoholic communion wine.

W.V. Wright & Co.'s coal-tar soap was first sold in 1860. It was originally named Sapo Carbonis Detergens, which remains a registered trademark.

In 1867, Wright moved his firm, Wright, Sellers & Layman, to small (one-third acre) premises at 50 Southwark Street, Southwark, London. This area of London was already renowned for its glue factories and tanneries.

Wright, Layman & Umney

Charles Umney (1843–1909) was taken into the partnership in 1876 when Mr Sellers retired, and the company's name changed to Wright, Layman & Umney "Wholesale and export druggists, manufacturers of pharmaceutical and chemical preparations, distillers of essential oils, manufacturers and proprietors of Wright’s Coal Tar Soap and other coal tar specialities". It soon became necessary for the company to lease adjoining premises, until in quick succession numbers 44, 46, and 48 were added to the original warehouse at Southwark Street.

1877: Wright dies

Wright met an 'untimely death' in Dundee in September 1877: "he caught a cold in the face, which developed into erysipelas, the inflammation extending to the brain, he succumbed with great suddenness at the age of fifty one". Erysipelas is an acute infection of the skin and underlying fat tissues, usually caused by the streptococcus bacteria.

Two of his sons, Charles Foster, born 1859, and Herbert Cassin, born 1863, in Clapham, Surrey, followed their father's footsteps into the wholesale drug trade, Herbert remaining on the board of directors into the 20th century. The eldest son, William Valentine Jr., born 1854, listed his occupation as "gentleman", while the youngest son, Sydney Faulconer, became a physician and surgeon.

1892: Charles Booth interview

In 1892 as part of a survey into life and labour in London, the social researcher Charles Booth interviewed Charles Umney. The original record is in the archives of the British Library of Political and Economic Science:

| “ | Mr Charles Umney of Wright, Layman, Umney 50 Southwark Street, S.E. Manufacturing Druggists. Employ 68 hands, Wages pw: 27/- to 32/- employment perfectly regular - the busiest months being Jan. Feb. and March, when there is most illness about. Everything turned out by a manufacturing druggist has to be supervised with the greatest care, as the retail chemist is never generally blamed for mistakes in prescriptions. The original sin may lie at the door of the manufacturer - for this reason over every department is placed an expert, a man who has passed examinations in chemistry, under the Pharmaceutical Society, & who is absolutely responsible for the smallest product of his shop. During the 18 years of Mr Umney’s experience two mistakes only had occurred. It is to the interest of this manufacturer to take all pains possible to avoid such accidents, as he may at any time be called upon to pay heavy damages should an accident occur. The raw drugs are exposed for sale once a week at some place near the docks. London used formerly to be the drug market of the world, but of late years other cities have attracted a part of this business, especially Antwerp, Amsterdam & New York. It is practically necessary to examine every bale before buying, & not be content with samples, as the greatest deceptions are sometimes practised. The chemicals are obtained from various parts of the country from chemical manufacturers - and are made up into drugs on the premises. Mr Umney was very bouttoné[1] - I was not taken over his factory. There are 7 or 8 manufacturing druggists in London & the number of actual workpeople employed would not amount to more than a few hundred.[2] | ” |

Park Street

With an increasingly acute accommodation shortage at the Southwark Street premises, the drug laboratories and soap factory were moved north to 66-76 Park Street, Southwark in 1899. The factory was enlarged in 1920.

During the 1930s the company bought the old business of Dakin Brothers in Middlesex Street.

In 1942, additional factory premises were built at 66 Park Street and in 1950 a new additional warehouse was built in Southwark Street. The total floor space was by then two and one third acres.

The soap works in Park Street have now gone, and Park Street has been almost entirely rebuilt. In Southwark Street, at eye level, the row of properties from the junction with Thrale Street (the old Castle Street) westwards looks wholly new, but that is only true of eye level; the shop-fronts and office-fronts have been replaced within the last forty or so years. Above these fronts, however, the architecture of the upper parts of Nos. 44 to 50 Southwark Street is clearly original Victorian. Nos. 44 and 46 form parts of what is now called Thrale House; No. 48 is called Saxon House; and No. 50 is separate again. The original roofline of Nos. 44 and 46, up to the Victorian cornice, survives, but Nos. 48 and 50 boast an additional modern attic storey. For much of the 20th century, Wright, Layman & Umney occupied all these properties.

Limited company

In June 1899 Wright, Layman & Umney became a private limited company with a capital of £100,000 and Charles Umney as director. Charles maintained an active role in the business until 1905 and subsequently acted as chairman of the company.

In due course, Charles' sons, Ernest Albert Umney and John Charles Umney, joined the firm, and Percy Umney became the company solicitor. By 1898, John Charles Umney had taken over the management of the Coal Tar Soap section of the business.

Readers of the Country-Side magazine in 1906 were offered the chance to buy an inexpensive cabinet frame for one shilling, in which they could stack twelve empty Wright's Coal Tar Soap packets to act as sliding drawers in a cabinet for natural history specimens. As the editorial mentioned: "the measurements have been chosen because so many of our readers are users of Wright's Coal Tar Soap". Wright's Coal Tar Soap was a regular advertiser in the magazine.

Public limited company

By 1909 the company was one of the leading pharmaceutical houses in the country, and in that year it became a public limited company with a capital of £135,000 with Charles Umney as chairman of the board of directors. The other directors were Charles Noel Layman (died 1909), Ernest Blakesley Layman, Herbert Cassin Wright, John Charles Umney, Frederick Noel Layman, and Ernest Albert Umney. Percy Umney was company solicitor; Ernest Albert Umney later became chairman of the company.

During the first year of trading as a public limited company, the product range was enlarged to include Wright's Coal Tar Shaving Soap in powder form.

By 1932, when a share issue of £280,000 was offered, the directors were Herbert Cassin Wright (chairman), Ernest Albert Umney (vice-chairman), Ernest Blakesley Layman, James Knight, James Hamerton, and Reginald Edward Conder.

Hampshire Museum

Hampshire Museum has four Coal Tar Vaporizers made by Wright, Layman & Umney in the early 20th century, and some bill-heads (invoices) which were sent to one of their customers, Messrs Charles Mumby & Co, lemonade manufacturers of Gosport.

Wright Layman & Umney Ltd v Wright

In 1949 the company sued a trader who used a similar name. The law at the time relating to trademarks was covered by the Trade Marks Act 1938. Case law shows that a similar name is not always certain to lead to an injunction. It has been stated that where a trader adopts words in common use, some risk of confusion is inevitable; it would be wrong to allow someone to monopolise words. A similar confusion will occur when many people have a similar name. In Wright Layman & Umney Ltd v Wright, 1949, the rule was stated as

| “ | If a man uses his own name, and uses it honestly and fairly, and is doing nothing more, he cannot be restrained, even if confusion results. | ” |

However, as in the case of Wright Layman & Umney v Wright,

| “ | once he oversteps the line and confusion results or is calculated to result, the fact that he is using something approaching his own name is no justification. | ” |

Takeover

In the late 1960s the Wright's Coal Tar Soap business was taken over by LRC Products (London International Group) who sold it to Smith & Nephew in the 1990s.

The soap is now made in Turkey for the current owners of the brand, Simple Health and Beauty Ltd based in Solihull in the UK and is called Wright's Traditional Soap. Simple Health and Beauty is part of the consumer goods company Unilever UK Ltd

Removal of coal-tar

As European Union directives on cosmetics have banned the use of coal tar in non-prescription products, the coal tar derivatives have been removed from the formula, replacing them with tea tree oil as main anti-bacterial ingredient. Despite this major variance from the original recipe, the new soap has been made to approximate the look and smell of the original product.

References

- ↑ bouttoné; "buttoned up", "tight-lipped"

- ↑ http://booth.lse.ac.uk/cgi-in/do.pl?sub=search_catalogue_pages&arg0=umney&arg1=and

External links

![]() Media related to Wright's Coal Tar Soap at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wright's Coal Tar Soap at Wikimedia Commons