Walking (Thoreau)

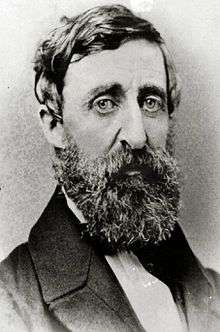

Walking, or sometimes referred to as "The Wild", is a lecture by Henry David Thoreau first delivered at the Concord Lyceum on April 23, 1851. Written between 1851 and 1860. Thoreau read the piece a total of ten times, more than any other of his lectures. "Walking" was first published as an essay in the Atlantic Monthly after his death in 1862. He considered it one of his seminal works, so much so, that he once wrote of the lecture, "I regard this as a sort of introduction to all that I may write hereafter." Thoreau constantly reworked and revised the piece throughout the 1850s, calling the essay Walking. "Walking" is a Transcendental essay in which Thoreau talks about the importance of nature to mankind, and how people cannot survive without nature, physically, mentally, and spiritually, yet we seem to be spending more and more time entrenched by society. For Thoreau walking is a self-reflective spiritual act that occurs only when you are away from society, that allows you to learn about who you are, and find other aspects of yourself that have been chipped away by society. "Walking" is an important cannon in the transcendental movement that would lay the foundation for his best known work, Walden. Along with Ralph Waldo Emerson's Nature, and George Perkins Marsh's Man and Nature, it has become one of the most important essays in the environmental movement.

Transcendentalism in Walking/Form

"Walking" is a transcendental essay that analyzes the relationship between man and nature, trying to find a balance between society and our raw animal nature.

"I would not have every man nor every part of a man cultivated, any more than I would have every acre of earth cultivated: part will be tillage, but the greater part will be meadow and forest".[1]

While Thoreau does not want man to be fully socialized, and lose his raw nature, he does acknowledge that part of man will always be, "tillage", farmers, or people cultivating land, people part of society. Thoreau is seeking a balance between the "savage" and "the civilized". The act of walking is transcendental in that walking is to not be in a hurry, to relax, and self-reflect, it is seeing yourself as part of nature, and being away from society and its busyness.

Part of Nature

"Walking" fits into transcendental ideas of the 1800s enlightenment period, by claiming that we are part of nature,

"I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil, -to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society".[2]

Thoreau believes that man is not a spectator looking at nature from a city that has conquered nature, but rather influenced by nature, as well as having an effect on nature. And because we are part of nature we have another aspect to ourselves that is wild and unrestricted by social norms.

Learn From Nature

Thoreau believes that when we are in nature we learn who we really are at our core,

"I derive more of my subsistence from the swamps which surround my native town than from the cultivated gardens in the village".[3]

According to Thoreau we learn more of who we when we are in nature because nature has not been shaped by society, and therefore when we are in nature, and away from society’s molding hands, we return to our natural selves.

Nature is a spiritual Experience

According to Thoreau, and just as Emerson, being in nature is a spiritual experience, which shapes who we are,

"For I believe that climate does thus react on man- as there is something in the mountain- air that feds the spirit and inspires. Will not man grow to greater perfection intellectually as well as physically under these influences?".[4]

When we walk, we take the time out of busy society to reflect, and according to Thoreau this self-reflection accompanied by trees, and fresh air inspires us and makes us better, spiritually, and intellectually.

Themes

"Walking" The main theme is Nature. Thoreau is looking at nature, and how nature brings self-reflection through the act of walking, how nature represents the wild natural aspect to man that has been suppressed by society, and criticizing society and people who think society is everything, and lastly Thoreau is trying to push us towards exploration particularity in the west, because at the a time the United States was living under the idea of Manifest destiny that promised westward expansion to fulfill a duty to cultivate and civilize land, however, for Thoreau the west represents a different kind of future with new opportunities.

Self-Reflection

Thoreau thinks that modern man is too distracted by society, so much so that people no longer take the time to enjoy how beautiful nature is, nor do they self-reflect. For Thoreau the remedy to society is the act of walking because it is an act of self-reflection and crusade,

"Moreover, you must walk like a camel, which is said to be the only beast which ruminates when walking".[5]

Thoreau wants us to walk like camels because they think deeply while walking then walking is to think deeply about yourself, rather than to be caught up in other concerns.

"In my afternoon walk I would fain forget all my morning occupations and my obligations to society. But it sometimes happens that I cannot easily shake off the village…What business have I in the woods, if I am thinking of something other than the woods?".[6]

Thoreau is trying to get people away from a mentality that is consumed by matters of business and society to think deeply about ourselves and our relationship to nature.

The Wild and Society

Thoreau often brings up this concept of the wild, as being a raw savage unbound nature that is natural to us but has been suppressed by society. Thoreau wants us to be aware and unleash this wild nature in us that is free. The wild is untamed, uncivilized, freethinking, and as Thoreau says,

""all good things are wild and free".[7]

Thoreau does not want us to be blind followers but he wants us to be unbound by society, to shape ourselves.

"" I rejoice that horses and steers have to be broken before they can be made the slaves of men, and that men themselves have some wild oat still left to sow before they become submissive members of society".[8]

Thoreau likes that all animals have to be trained to be submissive because it shows that animals, just as us are not naturally submissive creatures. Thoreau is weary of the amount of influence society has on an individual,

"here is this vast, savage, howling mother of ours, Nature, lying all around, with such beauty, and such affection for her children, as the leopard; and yet we are so early weaned from her breast to society, to that culture which is exclusively an interaction of man on man…".[9]

Thoreau wants us to break away from the hands of society and discover our relationship to nature.

Exploration

In "Walking" Thoreau is advocating for exploration in the west, because it represents untouched land, that is the opposite of the east with its old ideas and large cities.

"We go eastward to realize history and study the works of art and literature, retracing the steps of the race; we go westward as into the future, with a spirit of enterprise and adventure. The Atlantic is a Leathean stream, in our passage over which we have had an opportunity to forget the Old World and its institutions".[10]

Thoreau wants to move forward, walking is seen as a journey and adventure into the unexpected, so for Thoreau walking westward represents new exploration, and perhaps new society and man that is not so taken by the ways of the east. This idea of moving west ward can be related to the westward expansion of the 1800s when there was the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark expedition, and the idea of manifest destiny. "Between 1803 and 1853 the United States almost tripled in size. In the early 1800s, the land west of the United States was very undeveloped. Many considered it to be uncivilized and underdeveloped…However, the U.S. truly believe it was their Manifest Destiny, obvious fate, to spread the idea of liberty and democracy to this land. They also felt it was their duty to civilize it by bringing in roads, railroads, the telegram, etc."[11] Writing during this time Thoreau is building upon this idea of westward expansion not at a duty to civilize and cultivate the land but to take the opportunity to explore the land and learn from it spiritually, and create a new kind of society that allows man to be wild and self-reflective.

Historical setting

"Walking" was written between 1851-1860. During this time a large number of important works were published such as, Nathaniel Hawthorne's, The Scarlett Letter in 1850, Emerson's A Representative Man, Herman Melville’s MobyDick in 1851, Harriet Bleecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in 1855. Politically and socially, there was the 1850 compromise, and Kansas/Nebraska Act, as well as the Fugitive Slave act. The 1850 compromise and Kansas/Nebraska Act influenced Thoreau’s outlook on westward expansion, and how we had to preserve nature, how society was not everything, how there was much wild yet to be found, because at the time westward expansion was a cultural idea in the air.

"In the 1830s and onward, New England was the most economically progressive region of the United States. Textile mills were thriving and the region was key to the industrial revolution in the United States. The rapid growth of textile manufacturing in New England caused a shortage of workers and also changed the structure of the society. Thousands of farm girls left rural areas and family farms to work long hours in textile mills to support their families and widen their horizons. Immigration was steadily increasing" This way of the east can be seen as another reason why Thoreau rejected the east, and was worried that people would lose their relationship to nature.

The literary tradition that Thoreau is writing in is very much influenced by Emerson and his transcendental ideas. Emerson had been a mentor to Thoreau, and for two years while writing "Walden," Thoreau lived in a cabin he built himself on land owned by Emerson, and so Emerson’s ideas about nature and how we have a spiritual relationship with nature is seen in Thoreau’s writings. "Walking" is now regarded as a key work to the transcendental movement that has inspired many works of environmentalism.

Excerpts

"I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil—to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society".

"Let me live where I will, on this side is the city, on that the wilderness, and ever I am leaving the city more and more, and withdrawing into the wilderness".

"Ben Jonson exclaims: 'How near to good is what is fair.' So I would say: 'How near to good is what is wild.'"

"Here is this vast, savage, hovering mother of ours, Nature, lying all around, with such beauty, and such affection for her children, as the leopard; and yet we are so early weaned from her breast to society, to that culture which is exclusively an interaction of man on man"...

"So we saunter toward the Holy Land, till one day the sun shall shine more brightly than ever he has done, shall perchance shine into our minds and hearts, and light up our whole lives with a great awakening light, as warm and serene and golden as on a bankside in autumn".

See also

References

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 656. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 627. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 646. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 642. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 631. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 632. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 652. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 653. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 655. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry (2000). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 638. ISBN 9780679783343.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Amy (May 2, 2016). [from:http://www.csun.edu/~asr15199/westwardexpansion/ "Westward Expansion"]. Teaching U.S History. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- https://www.walden.org/documents/file/Library/Thoreau/writings/Writings1906/05Excursions/Walking.pdf