USS Sable (IX-81)

.jpg) USS Sable IX-81 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Greater Buffalo |

| Owner: | Detroit and Cleveland Navigation Company |

| Port of registry: | United States |

| Route: | Buffalo to Detroit |

| Builder: | American Ship Building Company of Lorain, Ohio |

| Cost: | $3,500,000.00 |

| Way number: | 00786 |

| Launched: | 27 October 1924 |

| Identification: | US 223663 |

| Fate: | Acquired by the United States Navy on 7 August 1942. |

| Name: | USS Sable |

| Namesake: | Sable |

| Acquired: | 7 August 1942 |

| Commissioned: | 8 May 1943 |

| Decommissioned: | 7 November 1945 |

| Struck: | 28 November 1945 |

| Fate: | Sold on 7 July 1948 for scrapping. |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 58 ft (18 m) (as Greater Buffalo and Sable) |

| Height: | 21.3 ft (6.5 m) (as Greater Buffalo) |

| Decks: | Seven (as Greater Buffalo) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | Sidewheel |

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h)[2] |

| Crew: | 300 Officers and men (as Greater Buffalo) |

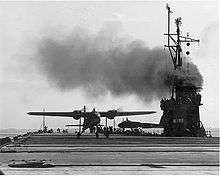

USS Sable (IX-81) was a training ship of the United States Navy during World War II.[3] Originally built the passenger ship Greater Buffalo, a sidewheel excursion steamer, she was purchased by the Navy in 1942 and converted to a freshwater training aircraft carrier to be used on the Great Lakes. Lacking a hangar deck, elevators or armaments, she was not a true warship. The main purpose of her creation was for the advanced training of naval aviators in aircraft carrier takeoffs and landings.

On her first day of service fifty-nine pilots became qualified within nine hours of operations, with each making eight takeoffs and landings apiece. Pilot training was conducted seven days a week in all types of weather conditions.[4] One aviator that trained upon the Sable was future president George H. W. Bush.[3]

Following World War II, Sable was decommissioned on 7 November 1945. She was sold for scrapping on 7 July 1948 to the H.H. Buncher Company. The USS Sable and her sister ship, the USS Wolverine, hold the distinction of being the only freshwater, coal-driven, side paddle-wheel aircraft carriers used by the United States Navy.[5][6]

Construction

Formerly named Greater Buffalo, Sable was originally built in 1924 by the American Ship Building Company of Lorain, Ohio as a sidewheel excursion steamer designed by marine architect Frank E. Kirby. Her hull number was 00786 and the official number assigned to her was 223663.[7]

The interior of the ship designed by W & J Sloane & Company of New York City in what was referred to as "an adaptation of the Renaissance style".[5] The ship's saloon was on two decks, 650 staterooms and an excess of 1,500 berths for passengers.[8][9] A twenty-two foot long transportation themed mural, painted by New York City artists Francklyn Paris and Frederick Wiley, was created on board the Greater Buffalo as well.[10] On the promenade deck at the stern of the ship was a smoking room with a line of windows that arced from one side of the ship to the other. Each room had a telephone with a central switch board located in the ship's lobby as well as motion picture equipment to show movies for passenger entertainment.[11]

When completed, Greater Buffalo was 518.7 ft (158.1 m) in length, a beam of 58 ft (18 m), height of 21.3 ft (6.5 m) and had a 7,739 long tons (7,863 t). She had nine boilers installed and was powered by a three-cylinder inclined compound steam engine.[1][12] She was seven decks high, carried three funnels along her top and carried a crew of 300 officers and men.[13] The final cost for construction was $3,500,000.00.[14]

History

Following a period of company growth during World War I the Detroit and Cleveland Navigation Company was able to order a pair of new ships for their Great Lakes routes.[8] The Greater Buffalo along with her sister ship Greater Detroit were among the largest side wheel paddle ships on the Great Lakes when she entered service in 1924.[15][16]

On her maiden voyage to Buffalo, New York on May 13, 1925 the Greater Buffalo carried a capacity number of passengers including T.V. O'Connor who was president of the shipping board at the time.[17] Greater Buffalo was used as a palatial overnight service boat transporting up to 1,500 passengers from Buffalo to Detroit for the Detroit and Cleveland Navigation Company.[3][18] Guests were entertained by an orchestra for dancing in the main dining room following dinner service as well as radio programming provided in the main salon.[19] Along with passenger service the Greater Buffalo, as well as other Detroit and Cleveland Navigation Company ships, offered their customers the option of transportation for 125 automobiles on their voyage.[9][20]

During the Great Depression the Greater Buffalo along with her sister ship were taken out of service from 1930 thru 1935. This, along with union disputes and worker strikes, caused continuing losses for her owners.[18] In 1936 the Greater Buffalo was docked at Cleveland and used as a "floating hotel" for attendees of the Republican Convention. The ship was reported to have broken free of her moorings and drifted out into the harbor during a storm but was brought back by harbor tugs.[21] During the 1938 season the Greater Buffalo along with the Greater Detroit were removed from service only to be returned to service the following year.[8]

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor there was a need for large vessels that could be converted into training aircraft carriers for pilot training.[18] The Greater Buffalo's length, following conversion, would be roughly two thirds the length of an Independence class aircraft carrier and it was felt by the navy that if pilots could master takeoffs and landings on the shorter deck they would have less problems transitioning to a standard length carrier. Other benefits by using her for training were that an active duty combat ship would not have to be used for training and with her location on the Great Lakes she would be out of the reach of enemy submarines and mines.[5] The Greater Buffalo was acquired by the Navy on 7 August 1942 by the War Shipping Administration to be converted into a training aircraft carrier and renamed Sable on 19 September 1942.[22]

Naval service

Refit

When leaving her port in Detroit for the last time heading for her refit it was reported that the Greater Buffalo was "saluted" by those on board the other vessels in the area.[23] Sable was converted at the Erie Plant of American Shipbuilding Company[24] at Buffalo, New York.[22] The cabins and superstructure of the ship were removed leaving the main deck. Along with additional supports, a steel flight deck was installed instead of the originally planned Douglas-fir wooden deck similar to what was installed on USS Wolverine (IX-64).[3] The steel deck also allowed Sable to be used for the testing a variety of non-skid coatings applied to the flight deck.[25] The deck of Sable was equipped with eight sets of arresting cables as well.[26] A bridge island or superstructure was constructed on the starboard side of the ship along with outriggers forward of the island for storing damaged aircraft.[4] On the main deck a lecture room, along with projection equipment, was constructed that could accommodate more than forty aviators with bunks for twenty one aviators. She was also equipped with a sick bay, operating room, laundry, tailor shop, crew quarters, a cafeteria style galley for the crew, a mess hall for the officers, storerooms and a refrigerator.[27] Sable lacked a hangar deck, elevators or armament, as her role was for the training of pilots for carrier take-offs and landings.[28] A number of crew members assigned to the Sable prior to her commissioning were survivors of the USS Lexington which had been lost earlier during the Battle of the Coral Sea.[29] Sable was commissioned on 8 May 1943 with Captain Warren K. Berner in command.

Training duty

The completed Sable departed Buffalo on 22 May 1943 and arrived at her assigned homeport of Chicago, Illinois on 26 May 1943 and were docked at what came to be called Navy Pier joining her sister ship USS Wolverine in what was casually referred to as the "Corn Belt Fleet".[22][30] Sable along with her sister ship, Wolverine, were assigned to the 9th Naval District Carrier Qualification Training Unit (CQTU) and qualified pilots for carrier operations. With the flight deck being shorter and lower to the water than a standard carrier it was felt that if a pilot could master take offs and landings then they would have less trouble when stationed on a standard carrier.[4] Pilot training was conducted seven days a week with the fifty-nine pilots becoming qualified within nine hours of her first day of service.[31] One issue that arose was that because of the lower top speed and height of Sable there wasn't enough "wind over deck" needed in order to launch certain types of aircraft or even carry out training on calm days.[25] In August 1943 Sable was used as a base for testing the experimental TDN-1 torpedo drone.[26]

Decommissioning and disposal

Following the end of World War II, Sable was decommissioned on 7 November 1945 and struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 28 November 1945.[22] Before she was to be auctioned off a proposal was made by the Great Lakes Historical society to have the Sable made into a museum for great lakes history at Put-in-Bay, Ohio near the Commodore Perry monument.[32] She was sold by the Maritime Commission to H. H. Buncher Company on 7 July 1948 and was reported as "disposed of" on 27 July 1948.[22] In order to fit through the Welland Canal, Sable was cut down prior to her journey to the ship breaking yard at Hamilton, Ontario. It was reported that 28 feet of her beam along with 50 feet of her stern flight deck were removed prior to her being moved by tugboats.[33] Even with the modifications the Sable only had five feet of clearance on each side while passing through the canal locks.

Legacy

Together, Sable and Wolverine trained 17,820 pilots in 116,000 carrier landings. Of these, 51,000 landings were on Sable alone. One of the pilots qualified on Sable was a 20-year-old Lieutenant, junior grade, future president George H. W. Bush.[3] Of the estimated 135–300 aircraft lost during training, 35 have been salvaged and the search for more is underway.[34][35] Both the USS Sable and the USS Wolverine hold the distinction of being the only fresh water, coal-driven, side paddle-wheel aircraft carriers used by the United States Navy.[5][6]

See also

- Frank E. Kirby

- Edward M. Cotter (fireboat)

- SS Canadiana

- Buffalo, New York

- USS Wolverine (IX-64)

- MV Aquarama

References

- 1 2 "Greater Buffalo.". Fr. Edward J. Dowling, S.J. Marine Historical Collection. University of Detroit Mercy. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ Silverstone, Paul H (1965). US Warships of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-773-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Greater Buffalo & The U.S.S. Sable". WNY Heritage Press. 2005. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 Polmar, Norman (October 24, 2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events. 1. 1909-1945. Potomac Books. pp. 272–273. ISBN 1574886630.

- 1 2 3 4 Duff, Steven (February 2001). "From Cruiseship to Warship". Vol LV, No. 2. Lakeland Boating. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- 1 2 "TV Special-Lake Michigan Carriers and the Aircraft Recovery Operations". National Naval Aviation Museum. March 1, 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ "Greater Buffalo Registry and Rig Information". Great Lakes Vessels Online Index. Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Robins, Nick (2012). The Coming of the Comet: The Rise and Fall of the Paddle Steamer. Seaforth Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978 1 84832 134 2.

- 1 2 "Marine News". The Ogdensburg Republican Journal. Ogdensburg, New York. October 27, 1924. p. 2. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "Beautiful Mural Paintings Installed On Passenger Boats" (PDF). Augusta Beacon. Augusta, Michigan. August 14, 1924. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "Peak of Luxury in Great Lakes Vacation Travel Provided by Two New Leviathans Costing $7,000,000". The Medina Daily Journal. Medina, New York. May 2, 1925. p. 4. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "GREATER BUFFALO; 1924; Steamer; US223663". Great Lakes Maritime Database. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ "Largest Lake Liner Arrives at Buffalo". The Milwaukee Journal. May 13, 1925. p. 1. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ Ahrens, Ronald (May 6, 2014). "Transformer Ships". Dbusiness Daily News. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ "Minnesota's Lake Superior Shipwrecks - History and Development of Great Lakes Water Craft". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form - Maritime Heritage of the United States NHL Theme Study Large Vessels - Columbia (Steamer)" (PDF). National Park Service. December 19, 1991. p. 9. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ "Ford May Buy and Operate 400 Government Ships, Greater Buffalo Made Maiden Trip". The Medina Daily Journal. May 14, 1925. p. 1. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Austin, Dan. "City of Detroit III". Historic Detroit.org. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ "Lake Season Continues Another Month". The Medina Daily Journal. Medina, New York. September 19, 1929. p. 1. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "Lake Tours via D&C Lake Lines". The Daily Times. Beaver, Pennsylvania. June 4, 1928. p. 6.

- ↑ "Many Grosse Pointers Attended the Republican Convention at Cleveland" (PDF). The Grosse Pointe Review. Grosse Pointe, Michigan. June 18, 1936. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Sable". Dictionary of American Navy Fighting Ships. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ "Convert Lakes Ship Into Aircraft Carrier". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. August 3, 1942. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ Erie Plant of American Shipbuilding Company

- 1 2 O'Malley, Dave (2013). "USS Wolverine & USS Sable Paddle Wheel Flattops of the Great Lakes". Vintage Wings of Canada. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- 1 2 "PADDLEWHEEL AIRCRAFT CARRIERS" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ "Well-Known Great Lakes Steamer Enters Service As Training Ship; Greater Buffalo Named U.S.S. Sable". Ogdensburg Journal. Ogdensburg, New York. May 8, 1943. p. 5. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "IX-64 Wolverine". Global Security.org. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ Morain, Dick. "Lewis C. Klotzbach". Universal Ship Cancellation Society. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ "Cornbelt Fleet Ends Service". The Southeast Missourian. UPI. April 17, 1970. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Bukowski, Douglas (1996). Navy Pier: A Chicago Landmark. Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-56663-115-0.

- ↑ "Famed Lake Vessel Sought As National Museum". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. June 16, 1948. p. 1. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ "USS Sable Heads For Scrap Yard". Odgensburg Journal. Ogdensburg, New York. October 21, 1948. p. 1. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "Historic WWII Aircraft Pulled From Lake". CBS News. 25 April 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ "NOAA SUPPORTS NAVY'S SEARCH FOR "SUNKEN WARBIRDS"". NOAA. 30 June 2004. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- Silverstone, Paul H (1965). US Warships of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-773-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Sable (IX-81). |