Ukrainians in Poland

|

Kievan Rus Foundation of St. Vladimir in Kraków with courtyard patio of a fine dining restaurant | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (51,000 (Census 2011),[1] 1,000,000 (Estimate 2016)) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| North east: Olsztyn, Elbląg; north west: Słupsk, Koszalin; south west: Legnica and Wrocław | |

| Languages | |

| Ukrainian · Polish | |

| Religion | |

| Greek Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity |

The Ukrainian minority in Poland (Ukrainian: Українці, Ukrayintsi, Polish: Ukraińcy), according to the Polish census of 2011 used to be composed of approximately 51,000 people. Some 38,000 respondents named Ukrainian as their first identity (28,000 as their sole identity), 13,000 as their second identity, and 21,000 declared Ukrainian identity jointly with Polish nationality.[1] However, far more realistic assessment of current situation was provided by the Ukraiński Świat Society in 2015 – with headquarters at Nowy Świat in Warsaw – putting the total number of Ukrainians in Poland at 400,000 by current estimate.[2] In January 2016 the Embassy of Ukraine, Warsaw, informed that the number of Ukrainian residents in Poland was half a million with permanent status, and probably around one million in total. Ambasador Andrij Deszczyca noted that Ukrainian professionals enjoy good reputation in Poland and in spite of their growing numbers Polish-Ukrainian relations remain very good.[3]

The number of applications for refugee status rose 50 times following Euromaidan. The overwhelming majority of applications are being accepted. Resulting from this, Ukrainians constitute 25% of the entire immigrant population of Poland.[2]

Traditionally, most numerous concentrations of Ukrainians would reside in the north-east (Olsztyn and Elbląg), north-west (Słupsk and Koszalin) and south-west of Poland (Legnica and Wrocław). In the years between 2005 and 2006 the Ukrainian language was taught at 162 schools attended by 2,740 Ukrainian students.[4]

Cultural life

Main Ukrainian organizations in Poland include: Association of Ukrainians in Poland (Związek Ukraińców w Polsce), Association of Ukrainians of Podlasie (Związek Ukraińców Podlasia), Ukrainian Society of Lublin (Towarzystwo Ukraińskie w Lublinie), Kievan Rus Foundation of St. Vladimir, pictured (Fundacja św. Włodzimierza Chrzciciela Rusi Kijowskiej), Association of Ukrainian Women (Związek Ukrainek), Ukrainian Educators' Society of Poland (Ukraińskie Towarzystwo Nauczycielskie w Polsce), Ukrainian Medical Society (Ukraińskie Towarzystwo Lekarskie), Ukrainian Club of Stalinist Political Prisoners (Stowarzyszenie Ukraińców - Więźniów Politycznych Okresu Stalinowskiego), Ukrainian Youth Association "ПЛАСТ" (Organizacja Młodzieży Ukraińskiej "PŁAST"), Ukrainian Historical Society (Ukraińskie Towarzystwo Historyczne), and Association of Independent Ukrainian Youth (Związek Niezależnej Młodzieży Ukraińskiej). The most important periodicals published in Ukrainian language include: Our Voice (Nasze Słowo) weekly, and Над Бугом і Нарвою (Nad Buhom i Narwoju) bimontly.[4]

The most important Ukrainian festivals and popular cultural events include: Festival of Ukrainian Culture in Sopot ("Festiwal Kultury Ukraińskiej" w Sopocie), Youth Market in Gdańsk ("Młodzieżowy Jarmark" w Gdańsku), Festival of Ukrainian Culture of Podlasie (Festiwal Kultury Ukraińskiej na Podlasiu "Podlaska Jesień"), "Bytowska Watra", "Spotkania Pogranicza" in Głębock,[5] Days of Ukrainian Culture in Szczecin and Giżycko ("Dni Kultury Ukraińskiej"), Children Festival in Elbląg (Dziecięcy Festiwal Kultury w Elblągu), "Na Iwana, na Kupała" in Dubicze Cerkiewne, Festival of Ukrainian Children Groups in Koszalin (Festiwal Ukraińskich Zespołów Dziecięcych w Koszalinie), "Noc na Iwana Kupała" in Kruklanki, Ukrainian Folklor Market in Kętrzyn (Jarmark Folklorystyczny "Z malowanej skrzyni"), Under the Common Skies in Olsztyn ("Pod wspólnym niebem"), and Days of Ukrainian Theatre (Dni teatru ukraińskiego) also in Olsztyn.[4]

History, and trends

Since World War II

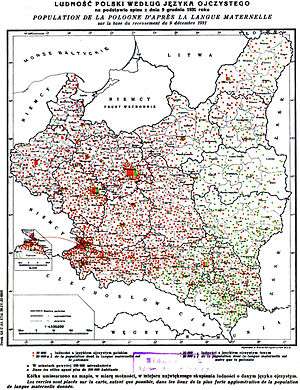

After the quashing of a Ukrainian insurrection at the end of World War II by the Soviet Union, about 140,000 Ukrainians residing within the new Polish borders were forcibly moved to northern and western Poland during Operation Vistula, settling the former German territories ceded to Poland at the Tehran Conference of 1943.

| Permits / Year | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | Total |

| Permanent Settlement Permits | 1,905 | 1,654 | 1,438 | 1,609 | 1,685 | 1,280 | 9,571 |

| Temporary Residence Permits | 8,518 | 8,304 | 7,733 | 7,381 | 8,307 | 8,489 | 48,736 |

| Grand total | 58,303 | ||||||

| Source: EU Membership Highlights Poland's Migration Challenges, Warsaw | |||||||

Since 1989, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, there has been a new wave of Ukrainian immigration, mostly of jobseekers, tradesmen, and vendors, concentrated in larger cities with established market. After the Poland's 2004 accession to the European Union, in order to meet the requirements of the Schengen zone (an area of free movement within the EU), the government was forced to make immigration to Poland more difficult for the people from Belarus and Russia including Ukraine. Nevertheless, Ukrainians consistently receive the most settlement permits and the most temporary residence permits in Poland (see table).[6] As a result of the Eastern Partnership, Poland and Ukraine have reached a new agreement replacing visas with simplified permits for Ukrainians residing within 30 km of the border. Up to 1.5 million people would benefit from this agreement which took effect on July 1, 2009.[7] Following the 2014–15 Russian military intervention in Ukraine, including its illegal annexation and occupation of Crimea ("Helsinki Declaration"),[8] the situation changed dramatically. Poland began taking in large numbers of refugees from the Ukraine conflict as part of the EU's refugee programme.[9] The policy of strategic partnership between Kiev and Warsaw was extended to military and technical cooperation,[10][11] but the more immediate task, informed Poland's State secretary Krzysztof Szczerski, was the Ukraine's constitutional reform leading to broad decentralization of power.[10]

The total of 27,172 people declared Ukrainian nationality in the Polish census of 2002. Most of them lived in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (11,881), followed by West Pomeranian (3,703), Podkarpackie (2,984) and Pomeranian Voivodeship (2,831).[4] Some Lemkos (recognized in Poland as distinct ethnic group) regard themselves as members of the Ukrainian nation, while others distance themselves from Ukrainians.[4]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011. GUS. Materiał na konferencję prasową w dniu 29. 01. 2013. p. 3. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- 1 2 Katarzyna Kunicka (October 19, 2015). "Ukraiński Świat. W Polsce mieszka 400 tys. Ukraińców" [According to Ukraiński Świat (formed in Warsaw during Euromaidan), 400,000 Ukrainians live in Poland]. Greenpoint Media 2015. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015 – via Internet Archive.

Ukraiński Świat jest ostatnią deską ratunku dla uciekających przed przemocą na Ukrainie do Polski, a także dla tych, którzy po powrocie do domu narażeni są na problemy gospodarcze. Raport, opublikowany 21 lipca przez Urząd do Spraw Cudzoziemców w Polsce pokazuje 50-krotny wzrost ukraińskich wniosków o status uchodźcy. Od 2013 do 2014 roku wnioski o pobyt czasowy wzrosły dwukrotnie, z 13,000 do 29,000. Wskaźnik ten cały czas rośnie: w ciągu pierwszych siedmiu miesięcy 2015 roku wyniósł ponad 32,000.

- ↑ PAP/Zespół wPolityce.pl (21 January 2016). "Ambasador Ukrainy: Milion Ukraińców w Polsce to migranci ekonomiczni". Wschodnik : Portal Informacyjny Aktualności z Ukrainy.

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Polish) Mniejszości narodowe i etniczne w Polsce on the pages of Polish Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Watra - spotkania pogranicza" (in Polish). Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- 1 2 Krystyna Iglicka, Magdalena Ziolek-Skrzypczak, Ludwig Maximilian (University of Munich) (September 2010). "EU Membership Highlights Poland's Migration Challenges". Center for International Relations, Warsaw. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Sikorski: umowa o małym ruchu granicznym od 1 lipca". Gazeta Wyborcza. 2009-06-17. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Pia. "2015 Annual Session Helsinki". www.oscepa.org. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

- ↑ PAP (28 August 2015). ""We can build European security together"". Office of the President of Poland. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- 1 2 Relacja Pawła Buszko z Kijowa (IAR) (4 September 2015). "Prezydent Ukrainy dziękuje Polsce za solidarność i zaprasza Andrzeja Dudę". Polskie Radio. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ Ukraine Today (25 July 2015). "Joint Military Brigade: Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania sign framework agreement". uatoday.tv. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

Further reading

- Dyboski, Roman (September 1923). "Poland and the Problem of National Minorities". Journal of the British Institute of International Affairs. 2 (5): 179–200. doi:10.2307/3014543.

- Roman Drozd: Droga na zachód. Osadnictwo ludności ukraińskiej na ziemiach zachodnich i północnych Polski w ramach akcji «Wisła». Warszawa: 1997. OCLC 435926521

- Roman Drozd, Igor Hałagida: Ukraińcy w Polsce 1944–1989. Walka o tożsamość (Dokumenty i materiały). Warszawa: 1999.

- Roman Drozd, Roman Skeczkowski, Mykoła Zymomrya: Ukraina — Polska. Kultura, wartości, zmagania duchowe. Koszalin: 1999.

- Roman Drozd: Ukraińcy w najnowszych dziejach Polski (1918–1989). T. I. Słupsk-Warszawa: 2000.

- Roman Drozd: Polityka władz wobec ludności ukraińskiej w Polsce w latach 1944–1989. T. I. Warszawa: 2001.

- Roman Drozd: Ukraińcy w najnowszych dziejach Polski (1918–1989). T. II: "Akcja «Wisła». Warszawa: 2005.

- Roman Drozd: Ukraińcy w najnowszych dziejach Polski (1918–1989). T. III: «Akcja „Wisła“. Słupsk: 2007.

- Roman Drozd, Bohdan Halczak: Dzieje Ukraińców w Polsce w latach 1921–1989. Warszawa: 2010.

- Дрозд Р., Гальчак Б. Історія українців у Польщі в 1921–1989 роках / Роман Дрозд, Богдан Гальчак, Ірина Мусієнко; пер. з пол. І. Мусієнко. 3-тє вид., випр., допов. – Харків : Золоті сторінки, 2013. – 272 с.

- Roman Drozd: Związek Ukraińców w Polsce w dokumentach z lat 1990–2005. Warszawa: 2010.

- Halczak B. Publicystyka narodowo – demokratyczna wobec problemów narodowościowych i etnicznych II Rzeczypospolitej / Bohdan Halczak. – Zielona Góra : Wydaw. WSP im. Tadeusza Kotarbińskiego, 2000. – 222 s.

- Halczak B. Problemy tożsamości narodowej Łemków / Bohdan Halczak // in: Łemkowie, Bojkowie, Rusini: historia, współczesność, kultura materialna i duchowa / red. nauk. Stefan Dudra, Bohdan Halczak, Andrzej Ksenicz, Jerzy Starzyński . Legnica – Zielona Góra: Łemkowski Zespół Pieśni i Tańca "Kyczera", 2007 pp. 41–55 .

- Halczak B. Łemkowskie miejsce we wszechświecie. Refleksje o położeniu Łemków na przełomie XX i XXI wieku / Bohdan Halczak // in: Łemkowie, Bojkowie, Rusini – historia, współczesność, kultura materialna i duchowa / red. nauk. Stefan Dudra, Bohdan Halczak, Roman Drozd, Iryna Betko, Michal Šmigeľ . Tom IV, cz. 1 . – Słupsk - Zielona Góra : [b. w.], 2012 – s. 119–133 .